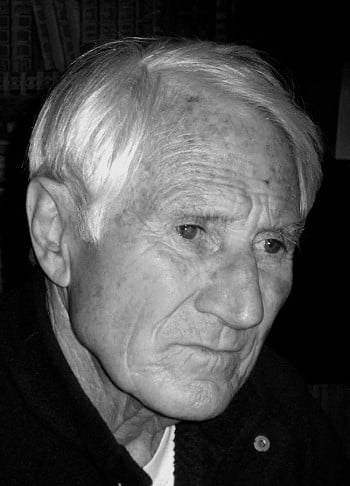

One is Doug Scott, who is recounting one episode of his 1979 ascent of Kanchenjunga, third highest mountain of Earth: his tent was literally disintegrated one night – in a few seconds – by a freak altitude wind, leaving him and his two companions (Joe Tasker and Georges Bettembourg) fighting for their lives against the elements, in total darkness, at 8000m. The other is a white haired gentleman, looking much younger than his 81 years, who is listening to Doug's tale through my impromptu translation, nodding enthusiastically to every detail, smiling sympathetically at this story of night terrors in the high places (something he knew all too well).

This is my last memory of Walter Bonatti, who died this September after a short fight with a sudden incurable illness.

It's very easy to apply, in these circumstances, too much existential weight to every detail of your last image of someone. But what I will remember forever of that night were his eyes – big eyes, like those of a child, still full, at 81, of a bottomless and insatiable thirst for new emotions. In the end, I feel that the most fitting epitaph for Bonatti's extraordinary career was "Curiosity drove all his life". Or maybe, on a second thought: "He never sold out".

But when asked the same question in a TV show, Walter had once replied "I want to be remembered as someone who lived life to its fullest". And he surely did. Born in 1930 in Bergamo, a town in Northern Italy not far from Milan, and from a very normal family background, his life had been changed forever (as millions of other Italians) by World War II. Northern Italy had been ravaged, first by the Allied bombing campaign, then by almost three years (1943 to 1945) of savage anti German guerrilla (and German/Fascist counterinsurgency) who had left the population starving and the nation's infrastructure in ruin. For him, as for many others, working as a steel factory worker had not been a choice but a matter of survival. But Walter had already proven himself as someone special. A restless child with his head full of adventurous dreams, and later a trained gymnast, he moved to Monza (near Milan) looking for a job where he became involved with a group of co-workers whose main interest was rock climbing. He thus got invited for few climbs in the Grigne, a group of relatively lowly but very rugged spires near the lake of Como. The encounter with actual rock climbing (before that he had only hiked in the safety of trails) was an important act of self discovery. A natural climbing talent, Walter soon discovered that for him being "good" was not enough – from day one he longed to test his limits. And from day one it was clear his limit seemed to be impossibly high.

In just two years, together with his friend (and co worker) Andrea Oggioni, he stunned the Italian climbing world by completing very early repeats of several much-feared alpine routes, including the Cassin route on the Walker spur of the Grandes Jorasses (4th ascent). For anyone else this could have been "just" an incredible climbing achievement, but for Walter – who seemed to treasure the emotions of climbing rather than just their sport value - it became the beginning of his life long love story with the Mont Blanc area. He returned there every year, using his tiny savings to pay for his train ticket and a spot in a campsite in Val Ferret, near Courmayeur. Already at the top of the game at 19, that was not enough for him – the bar had to be moved higher. The East Face of the Grand Capucin, an incredibly vertical rock obelisk rising from the Glacier du Geant that, together with Luciano Ghgo, he climbed in 1951, gave the world the first idea of what for Walter Bonatti was "raising the bar". Everyone (including arms of the national press not normally interested in climbing) began to take notice. A series of high profile repeats and first ascents followed – and then, in 1954 (after he had finished the then compulsory military service in the Alpine Corps) Walter was selected for the forthcoming Italian attempt to climb K2, second highest mountain of the world, and possibly the most difficult and coveted. When he returned home, his life had changed forever, but not for the reasons he had anticipated or hoped for.

A lot has been written on the 1954 K2 expedition and the controversy that followed (mostly for the wrong reasons) and it would be impossible in this short space to give the whole saga its due. With the hindsight of almost 60 years, my personal feeling is that K2, far from crippling Walter's human trajectory, became the occasion to focus his already considerable energy and will power, and embark on a 10 year "glory ride" (and a remarkable personal history of human growth) without equals in mountaineering lore.

The next step for Bonatti following the K2 drama and some of its unpleasant implications was the SW Pillar of the Petit Dru, the place was where the Bonatti legend (and Bonatti's "superstardom") was truly born. In an age when admiration for "heroic" mountaineering feats was not yet reduced to a guilty pleasure, his week-long fight on one of the Alps' most aesthetic walls captured the public imagination, to a level that only pre-war giants like Cassin or Comici could have dreamed of. Walter became, almost overnight, an international celebrity, particularly – and peculiarly – in France, a nation not exactly known for idolising foreigners, and that had many reasons to feel jealous of this Italian who had "stolen" one of its most prized climbs. Instead, France (as well as Italy) embraced him as the future of climbing

In the next five years, he climbed at a level almost unheard of by his contemporaries, mostly on his beloved Italian side of Mont Blanc ("I'm a son of Mont Blanc", he loved to repeat). He became a guide and in 1957 moved to Courmayeur (a town with whom he developed a long and complicated love-hate relationship). Always haunted by the K2 debacle, he climbed also abroad, most remarkably in 1958, making a spirited attempt on Cerro Torre and then summiting Gasherbrum IV (Perhaps the world's most difficult sub-8000 peak) in a expedition conceived as the "anti K2", but that had its own share of problems. Each attempt or successful climb, which were reported through the pages of Italian weeklies, made his name bigger. And we're speaking film or football star status here. It may be difficult outside Italy to imagine the idolatry the name Bonatti did conjure, but this fame went to such extremes that at one point he had to take measures to protect his privacy, something few other climbers had been forced to do. Meanwhile, he had another brush with the wrong side of climbing notoriety when he and client Silvano Gheser had a close call during the first winter ascent of the Brenva Spur of Mont Blanc, in a storm that later claimed the lives of French climbers Henry and Vincendon in a notorious – and to this day controversial – tragedy. Bonatti had nothing to do with the death of the two Frenchmen (who were lost on the French side of the mountain after an ill mounted rescue attempt), but it wasn't impossible to avoid the impression that with each new climb, the risk to which Bonatti was exposing himself increased exponentially, and controversy seemed always but a few steps behind him.

He could have taken this rise to fame for granted, but he didn't. He stuck to his own personal code of conduct, never deviating from his own self imposed rules, and often cutting short friendships and relations when he felt others were disappointing him. He refused sponsorship (a practice he frowned upon), making ends meet through guiding, selling articles and images, or via rare public appearances. He had few regular climbing companions, mostly friends (plus some regular clients) like Carlo Mauri (with whom he climbed GIV) and a few Courmayeur locals (Toni Gobbi but also Gigi Panei, a man who shared some of Bonatti's traits). His longest serving climbing mate of the 50's was however Andrea Oggioni, another friend of his factory days in Monza. In many ways Oggioni – a simple but incredibly strong man - was Bonatti's opposite. But they formed a complementary partnership that worked very well, with Walter providing the vision, and Oggioni the reliable support. Together they attempted (and succeeded) on several high profile climbs (let's mention here, in passing, the Red Pillar of Brouillard, still a beautiful classic to this day).

Then, in 1961, came the Freney Pillar catastrophe – in the view of the author of these notes, Bonatti's definitive climbing feat. In July 1961, Bonatti, Oggioni and their client Gallieni, became trapped 150 metres below the top of the Central Pillar of Freney, a stone monolith on the Italian side of Mont Blanc, and back then the "last great problem" of Alps. They were not alone, as a separate group of four French climbers (Mazeaud, Kohlmann, Vieille and Guillaume) had joined them in the later stages of the climb. Because of a completely unexpected summer storm (that lasted for days, covering the mountain with metres of snow down to 2000m), the group was forced to retreat in semi winter conditions. In normal circumstances, their bid for safety would have been doomed – almost invariably, people trapped high on the Italian side of Mt. Blanc die after no more than three or four days. But they had Bonatti with them. Walter took a daring tactical decision, knowing their only chance was to rapidly lose altitude, at the same time to avoid being avalanched. He thus decided for an improvised descent via the Rochers Gruber, a remote spur connecting the bottom of the Central Pillar with the Freney glacier (and the valley) below. Nonetheless, two of the French (Vielle and Guillaume) died in rapid succession because of exhaustion, while another (Kohlmann, who was born deaf and had been struck by lighting) showed increasing signs of disorientation.

Bonatti pushed the survivors forward, opening the descent route in knee deep snow and appalling weather. Meanwhile, a rescue attempt mounted in Courmayeur floundered at the nearby Gamba hut because of confusion on the objectives and lack of equipment. With a desperate effort, the survivors forced their way across the Freney glacier and up the steep Col de L'Innominata trying to reach the Gamba hut and safety. But at the col Oggioni, who had probably outstretched his resources, collapsed and died in Mazeaud's arms, while Kohlmann, now completely uncontrollable, died of an heart attack shortly after being reached by the rescuers. In the end, only Bonatti, Mazeaud and Gallieni survived - three out of seven. Bonatti arrived at the Gamba hut in a state that the rescue team medic (Pietro Bassi) defined "beyond any chance of survival", but still managed to live. Mazeaud was severely frostbitten, but Gallieni survived almost unscathed.

The book popularity ensured Walter's fame skyrocketed, and he continued to be a household name both at home and internationally. But to him something started to not feel right. Climbing at such a high level had become more and more dangerous, and less and less satisfying. His guiding work bored him, and his personal life was getting complicated – some of his relations with the Courmayeur establishment had turned rather tense (it must be said, often for non-climbing reasons) and even his marriage had begun to be shaky. By 1965, he wanted out. He did it in the Bonatti way – with a bang. After an initial attempt with two mates, he climbed solo a direct, incredibly hard route on the North Face of Matterhorn – Whymper's mountain, and a conscious homage to the great British climber and the tradition he meant. When he returned home, he found the tyres of his car slashed. While there are indications this had nothing to do with his role as a mountaineer, Walter felt this was yet another sign he had to move on. He officially "resigned" from jet set alpinism, and left Courmayeur (and guiding) a couple of years later.

And then he re-invented himself. Vertical adventure was not anymore his only obsession - he had spent most of his childhood daydreaming of adventures in the deserts or the jungles – it was time for him to live these dreams. His deal with Epoca (a popular Italian magazine) allowed him much more freedom than any sponsorship could. And so, Walter Bonatti began to travel around the world, and his re-invention from climber to "professional" reporter was a huge success. Epoca trademark stories "from our envoy Walter Bonatti" gathered an immense readership. In many ways what Walter did was just re-brand the same qualities he had displayed as a mountaineer for a different job. Resilience, courage, an good sense for what the public wanted to vicariously explore, a talent for interesting pictures, and the realisation that readers were often more interested in reading about the emotions of travel adventures rather than the adventures themselves.

It worked, and for more than a decade Walter found a new equilibrium, and a sense of happiness and fulfilment that – probably – his "great days" on the mountain had denied him. When remembering his travels abroad (particularly in remote places like the Poles or the African wilderness) he always stated that, more than anything else, he had enjoyed himself immensely. Not that he gave up climbing: he continued that for all his life, often in his beloved Mont Blanc range, often at level only barely below his prime. But he did that for his own pleasure, strictly as a private endeavour, to be shared only with a few friends. "Public" Bonatti was the adventure journalist – Bonatti the climber was still there, but now closed from public view.

Polemics, sometimes of the ugly variety, continued however to pursue him. For instance someone decided his "solo" trips were not solo at all, because several of his self portraits in the wilderness couldn't have possibly been shot without assistance. So – much to the chagrin of Walter himself – Epoca had to reveal that Bonatti was equipped with a state of the art radio-controlled self shooting device.

Walter's stint as a professional reporter more or less ended in 1980, after his relationship with Epoca came to a close - typically on a matter of principle. By that time, he was undergoing yet another "change crisis", a moment of his life when his priorities got shuffled again. While the new climbing generation around the world was revering his achievements and indicating him as a symbol of climbing purity to follow, in Italy (for a curious inversion) the next wave of climbers beheld him as a relic of the past, a symbol of a "heroic" climbing fashion that had no place in what was perceived as a future of hedonistic and "safe" climbing. He didn't like or even understand the use of bolts, and had no qualms to speak out publicly how he thought climbing had fallen prey to a technological obsession that was killing the spirit of adventure. However, while becoming distant from the Italian scene (his early enthusiasm for Reinhold Messner's achievements floundering when Messner – in his view – "sold out") his contact with foreign climbers (particularly English speaking ones) made him partially change his mind about the "new breed". On the other hand, a meeting with actress Rossana Podestà wasf or Walter another great boost of self-confidence. A self styled loner ("I don't know if I was born an outsider or I became one" may have been his signature phrase), he found in Rossana a like minded individual ready to follow him everywhere and learn from him the meaning of adventure. Once a famous actress, Rossana had publicly stated that "to carry the cameras for Walter Bonatti" (or "to be his little sherpa") could have been her dream job. She did much more, providing Walter with support and love that lasted for the rest of his life - and finally, when Walter suddenly fell ill of the pancreatic cancer that killed him, taking the terrible responsibility not to tell him about his condition, and nurse him to the very end.

His relationship with the Italian climbing establishment took a long while before being settled. Despite winning a lawsuit against a journalist who had accused him of stealing oxygen on K2 from the summit team, he never reconciled with Achille Compagnoni (who, in turn, maintained his own version of the K2 events to the end of his life), and from the end of the 80's onward, he launched a wide press campaign to see the official narration of the climb being changed to take in account his own version. In the end, and after an almost never ending stream of articles and publications – and only after Ardito Desio, the 1954 expedition leader, had died – the Italian Alpine Club (CAI) agreed on most of Walter requests. The final result was a compromise that didn't satisfy anyone, and probably did not fully satisfy even Walter (because no one could give him back his chance to summit K2). But at least gave him the sense of closure he much needed.

He continued to climb at a very high level well into his 70's (the last time he climbed Mont Blanc was via the serious Innominata Ridge) and to travel abroad, always accompanied by Rossana (and sometimes with not negligible risks for both). With the K2 controversy more or less solved, and after a long hiatus, he returned to some selected public appearances, discovering with some surprise that very little of his charisma had evaporated with the years. The younger generations, who knew him as an icon of the past, discovered a man with a strong code of conduct (something sorely missing in some quarter of today's Italy), radiating intelligence and self confidence despite his age. While still fiercely protecting his own privacy, he seemed to enjoy enormously the renewed contact with the public on TV, and later in places like the Festival of Trento or the Piolet D'Or (an event to whom he became a regular of sorts after the prize was "re-designed" in 2007).

But one single moment of this renaissance seemed to have captured his imagination. In 2007 he was offered honorary membership of the British Alpine Club, something he readily accepted. The official ceremony was held in Zermatt, the evening of solstice of 2007, in the magical sunset of the same day the Alpine Club celebrated its 150th birthday. Walter gave a short speech (in Italian) on the terrace of the Riffelberg, with his usual strength and authority, and few of those present will forget his voice and his image against the backdrop of the Matterhorn in the golden evening light. It was like Walter had added to an already solemn moment the kind of extra dimension only someone of his status could provide.

We met again the next day, outside a nondescript restaurant on a nondescript street of Zermatt. We exchanged few words (he was with a group of friends, I was with my family). I asked him how he had liked the previous night's ceremony. "Wonderful, wonderful", he replied with enthusiasm "And remember – these people" – he meant the AC members – "they always had the right attitude. They never sold out, really." And he smiled.

Comments