In this short article UKC Chief Editor Jack Geldard looks at a few simple and not so simple ways of improving your belaying. From soft catches to giving out biscuits, there's some tips here for almost everyone.

1: Take it seriously

For active climbers belaying is a daily occurrence. It's 'no big deal'. Many belaying accidents occur when experienced climbers, who are fully aware of the mechanics of belaying, get sloppy.

You have your friend's life in your hands. If you mess it up they may die. It is a 'big deal'.

This may sound melodramatic, but in fact, it is true. Take your belaying seriously. Your climber will appreciate it. It's not cool to pay out loads of slack and let go of the rope. It is cool to climb all your life, have loads of adventures, and never drop anyone or be dropped yourself.

2: Gauge the distance

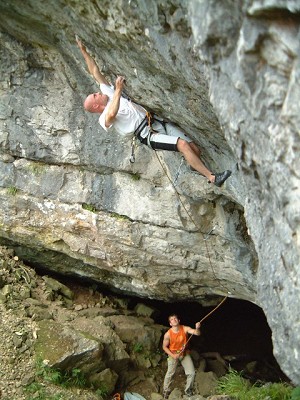

When a climber falls, they often go much further than you may have anticipated. Ropes stretch, slack in the system builds up, belayers move, runners pop. Even a 'slump' from just above a bolt or gear can result in a fall of several metres. Being aware of when it is crucial to minimise the distance of a fall is a key skill in belaying. When your climber is close to the floor or a ledge are the times when a short fall is essential for safety. Huge falls with 'soft catches' (see point 7) are great when your climber is high above the floor, with bomber gear or bolts, and a lot of space in which to fall. If they are at the second bolt of a short route with a bad landing, you should do everything you can to minimise the length of any fall they might take. This means having next to no slack in the system, making sure you are close in to the wall to avoid being pulled forward (even a single step forward can increase the distance of fall by around a metre, and this can be the difference between a smiling climber and a broken heel bone). You may need to think about weight difference here too. Are you much lighter than your climber? If so anticipate the fact that you will get pulled off your feet or very easily pulled forwards. This will of course increase the length of fall.

Do your sums, gauge your distances. Keep your climber off the ground.

3: Know your climber

Some people like encouragement, others do not. Some people like to know that their belayer is with them and appreciate some vocal confirmation of your concentration. A simple 'go for it Brian' can be enough, or a quick 'I'm watching you' as they move in to the crux. Not all climbers like encouragement. Get to know your climber, and try your best to give them the support or encouragement they need.

Don't be a beta sprayer, jibber-jabbering on and annoying your climber if they don't like that. But equally, don't stand in stoney silence if a few words of encouragement can help your intrepid leader commit to that crux.

Also, getting to know your climber will give you many indicators that allow you to belay proactively. For example if the disco leg starts, you may know that Graham is about to peel off. Or you may know that when Terry shouts 'watch me' what he really means is 'hold on I'm about to take a 30 footer!', or if Suzanne says "I'm going for a quick look" that means you had better be ready because she will be fighting for her life all the way to the top. Different climbers have different 'tells' - it's like a vertical game of poker.

4: Have the right equipment

And know how to use it!

There are two different types of belay device; those that lock the rope, and those that do not. 'Autolocking' or 'assisted' belay devices (see this UKC video article) are generally not recommend for trad climbing, as they put more force on trad runners due to grabbing the rope and not giving a 'soft catch' (see tip 7), but they can be excellent for sport climbing.

Whatever your device, be it a normal belay plate or an assisted device, make sure you know how to use it, and its limitations.

One tip is; if you are using a 'guide plate' or a Reverso style belay device to bring up your second (this is a belay plate that will auto lock whilst you are belaying a second, and these are often favoured by guides and instructors), then if it is on autolock mode, make sure you know how to release it, otherwise you can't lower your climber downwards, which is sometimes useful.

And, when the plate is used in this mode, it is really easy to give your second an overly assertive belay, jerking them upwards, and often whacking them in the face with the rope. Be constant but gentle with your top rope belaying, and give your second a much nicer climbing experience.

Other belaying equipment: In many indoor walls there are 'sandbags', and I'm not talking about routes that are hard for the grade. I'm talking about portable ground anchors. If you are using a sandbag, clip it to the belay loop on your harness (see this UKC article about Belay Loops) and stand with it slightly to your side, and slightly behind you, with no slack between you and the bag, otherwise if your heavier partner does pull you off your feet, the extra weight of the bag won't engage until you take up the slack in the system (ie by flying forwards!). The bag should not be in front of you with a loop of slack between you and it!

5: Be proactive, not reactive

Don't just stand there like a wally, you have a job to do. And like many aspects of life, you can do a bad job if you're not careful. You need to be able to anticipate what the climber is going to do, before they do it, to give you enough time to pay out or take in rope without affecting the climber's flow. When they are tugging on the rope for slack, and you haven't given it, then you're being 'reactive'. Having spotted them place some gear, shake out, and then reach for the rope, you anticipate the next move, and pay out some slack just milliseconds before they need it.

Here are some ideas:

Before they climb: Have a good look at the route, anticipate where your climber is likely to need rope, where they are likely to fall, and try and spot any possible run-outs or dangerous sections. Move in to the wall, and be prepared to move to the side, or quickly switch sides, if you find your rope is going to get in the way of your climber.

When they start: Keep in close to the wall (and I mean close!). Move the rope around with your upper hand, making sure it isn't getting tangled around your climber's legs or getting in the way of crucial footholds. Be quick to pay out rope for the first few pieces of gear or bolts. As you have no excess slack in the system at this point (see point 2 above) then you need lightning reactions.

6: Do a partner check

Simple. Check the knot, check the harness, check the belay plate. All tied in? Then you're good to go. A 5 second check could save your life.

7: Give a soft catch (Dynamic Belaying)

In a lot of circumstances, giving a 'soft catch' can make a fall more comfortable, safer, reduce impact on belayer, climber and gear, and generally be a great idea. Think of Dave MacLeod in the film E11, his ankle slamming falls made that route look terrifying. Sonnie Trotter attacked the same route, took the same falls, but with a 'soft catch' he sustained no injuries (I'm sure his trousers were a bit brown though...!). However, like mentioned above, you have to keep your climber off the deck, and sometimes soft catches are not appropriate. For more information see this UKC article on Dynamic Belaying.

8: Tie a knot in the end of the rope

You don't want to lower your partner off the end of the rope, which is quite a common mistake on long sport routes. Always keeping the unused end of the rope tied up in someway can prevent this accident. Either add a small knot to the end, keep the end of the rope tied on to the rope bag, or sometimes when trad climbing, you can keep yourself tied in to the bottom of the rope. Whatever you tie in to, make it a habit.

9: Wear a helmet

Rocks fall down, climbers drop gear, and belayers are generally underneath climbers. It makes sense to wear your helmet, not just when you are climbing, but when you are belaying too. Being tied in to the rope also means you have less ability to 'dodge' any falling missiles. Another good reason to put you lid on. Have a look at this UKC article on helmets.

10: Bring a treat

Climbers are like pets; they are pretty simple, but spending time with them can be rewarding. After your climber has pulled off the lead of their life, give them a treat. I always take little climber's biscuits - everyone likes a biscuit! Or maybe a sandwich. And if you keep your climber happy they might even agree to belay you in return!

- SKILLS: Building Fast Belays When Multipitch Sport Climbing 9 Nov, 2016

- SKILLS: Abseil Knots Explained 2 Oct, 2016

- FEATURE: Colm Shannon's Deserted DWS Heaven - Irish West Coast 7 Aug, 2016

- SKILLS: Acclimatising for the European Alps 5 Jun, 2016

- Terra Unfirma! Adventures on the Lleyn Peninsula 1 Jun, 2016

- VIDEO: Fiesta De Los Biceps 8 May, 2016

- REVIEW: Evolv Shaman 2016 18 Mar, 2016

- REVIEW: Doug Scott - Up and About 2 Feb, 2016

- ARTICLE: 12 Climbing Adventures That Won't Break The Bank 26 Jan, 2016

- DESTINATION GUIDE: 10 Routes to Climb in Chamonix in Winter 20 Jan, 2016

Comments