As 2014 clocked in, an unremitting calendar of WWI centenaries began to bring the events of that inconceivable year to the present. In climbing heritage 1914 was a year of tragic juxtaposition, and a new exhibition by the Mountain Heritage Trust at Keswick Museum explores the impact of the war on a climbing community high on ambition and psyche.

The 14th of April marked one hundred years of HVS with the anniversary of the infamous Central Buttress (C.B) route which takes a bold 5b line up the main face of Scafell. Thugging our way up classics, shoving sticky rubber in wet cracks, we might momentarily wish for big boots, but not much else from 1914. One of the first ascentionists, Siegfried Herford was twenty two that spring, spending one hundred days on the grit whilst studying for his finals at Manchester Uni, a sordid amount of time. Even a student climber would have cravenly waited for a one week holiday in a National Park or if posh, the Alps. Grit was too short to be considered worth bothering with by the Victorian summit baggers. But a new movement of 'climbing acrobats' explored the Yorkshire and Peak outcrops, practising balance rather than the jug hauling typical to mountain crags. Their elders considered this distasteful in the extreme, fearing the loss of their traditional aesthetic and bettering experience to the next generation of "indifferent mountaineers, with a somewhat limited way of regarding mountains", (R.L Irving.) The dreaded 'plastic pullers' of their day.

However, developing 'the doctrine of descent' (as he termed down-climbing in his article in the 1913 FRCC journal) on the grit meant Herford could attempt harder Lakeland lines with a greater margin of confidence, if not safety. He is one of an archetypal line of smart, challenging climbers who push the sport forwards by decades with a single route. In his case, C.B, thought of as the last climbable line in the Lakes, the area receiving the majority of action during that period. Finding a sympathetic partner in the quietly committed climber George Sansom, they 'worked' the Central Buttress route over two years, abseiling sections to practice cruxes. In a letter written to a friend in 1913 Siegfried described their efforts:

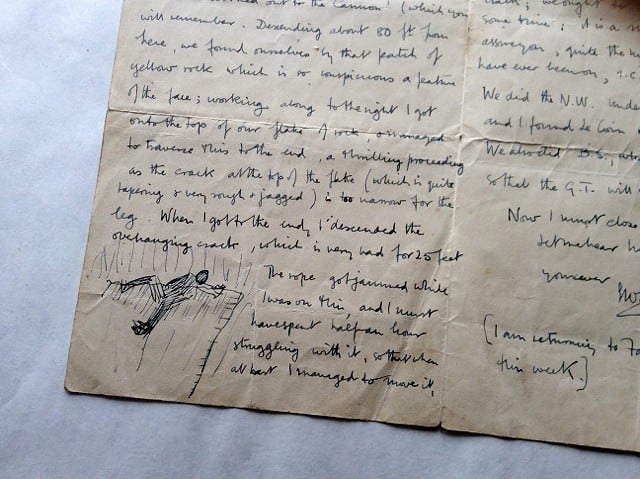

"I descended the overhanging crack, which is very bad for 25 feet. The rope got jammed while I was on this and I must have spent half an hour struggling with it, so that when at last I managed to move it, I was too tired to go up again, and had to descend. At any rate, the C.B problem is solved as much as it will ever be."

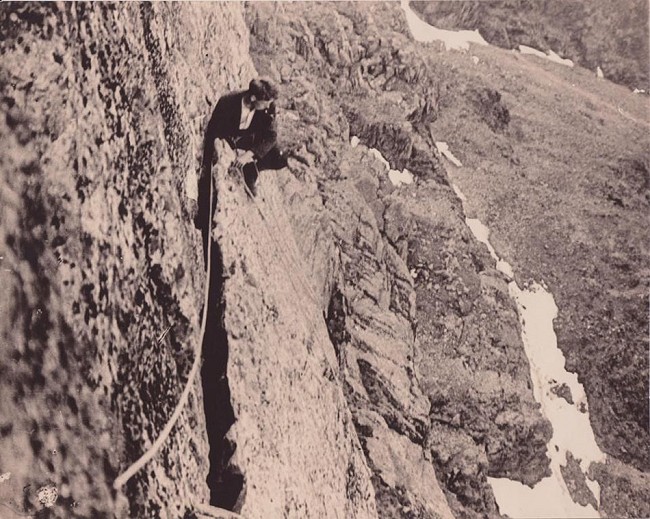

The image of a tweed-suited gent hanging from a jammed hemp rope, with no anchors, several hundred feet up a mountain crag is sketchy to say the least, so it seems reasonable that Herford decided the final crack crux wasn't worth it. However then as now, routes nag, and a team of four returned the following year. Siege style and with a smattering of 'combined tactics' - the odd limb where a dyno wouldn't do and the route was climbed, albeit in two parts. The impact of the ascent has no real modern equivalent, perhaps a 'Dawesian' style vision? The physical challenge of the route was huge, it still scalps climbers today, and a key psychological achievement for these young guns was releasing their climbing rat from social diktat. The 'two-fingers-up' audacity in undertaking what was seen by an austere older generation as an 'unjustifiable risk'.

Herford was twenty four when he was killed by a grenade blast near Festubert in January 1916. Perspectives on what was then seen as justifiable seem grossly skewed now. It's hard to know what individual climbers would have really felt about the events of that year. Religion, patriotism, faith in government are all ideas we find hard to equate now and the savage personal loss is absurd. The newly thriving FRCC lost a third of its enlisted membership in WWI. George Sansom survived and did continue to climb, though in the shadow of Herfords's death. C.B wasn't touched for years and the era of development promised by it's ascent disintegrated. Climbing and war seem odd things to parallel, yet there are undoubted parallels, questions. Enough to drive a generation away from the crag, and in other times to galvanise them back. The FRCC bought 1184 acres of the Lakeland fells as a commemoration of those lost, dedicating the mountains to the memory of men of the land. Last Sunday was the 90th anniversary of Geoffrey Winthrop Young's dedication on the summit of Great Gable in front of five hundred people in 1924:

"Upon this mountain summit we are met today to dedicate this space of hills to freedom, upon this rock are set the names of men - our brothers and comrades on the cliffs, who held with us that there is no freedom of the soil where the spirit of man is in bondage, and who surrendered their part in the fellowship of hill and winds and sunshine, that the freedom of this land, the freedom of our spirit should endure. By this symbol we affirm a twofold trust that which only hills can only give their children, the discipline of strength in freedom, the freeing of the spirit through generous service, that these free hills shall give again and for all time."

Among the exhibits at the Mountain Heritage Trust Exhibition at Keswick Museum are Herford's letters describing his attempts on Central Buttress, with stick-man 'beta' drawings of the crux. Also included is the camera belonging to the Abraham brothers, the first climbing photographers, which was carried up Scafell this April by Henry Iddon, Simon Gee and Adam Hocking as part of a live heritage project to mark the C.B centenary. The exhibition articulates the real dynamism of this generation of climbers, and the way their community made sense of the confusion of a justified war. If it's raining in the Lakes, or even if it's not, it's worth a visit.

You can follow MHT on Twitter and Facebook, or get in contact with Claire or Maxine about accessing the Collection or it's use for projects and events.

- ARTICLE: The Best Routes in the Lakes 27 Jul, 2016

- INTERVIEW: Shauna Coxsey on Comps & the WCS 3 Sep, 2014

- New to SteepEdge ? The Cairngorms in Winter with Chris Townsend 21 Jun, 2013

Comments