We've all been there: climbing smoothly, precisely and in control until suddenly the inevitable happens: your arms turn to fudge and no matter how hard you try to keep going, they become as much use as a chocolate teapot. Sticking with the crockery theme, the French call being pumped "avoir les bouteilles" or "to have bottles for arms." A very apt description, one might think...

While getting pumped is all part of the game when pushing hard and is directly related to your level of fitness, there are tips and tricks for improving your climbing technique which can help delay the onset of muscle fatigue and lactic acid build-up. Of course, the obvious solution for delaying pump would be to train harder, climb more regularly or regress to a pre-pubescent physique (children don't tend to get pumped before puberty*), but in the meantime there are some tips and tricks which many climbers take a while to discover or may not be aware of entirely.

The aim of this article is to run through some simple tactics, techniques and changes to your climbing style which will render your movement more efficient and ultimately - and most importantly - help delay the onset of pump and minimise its effects.

*Children respond differently to exercise and training since their metabolic systems are not fully developed.

What is Pump?

A bit of biology to begin with...

Pump is that universally-recognised sensation of engorged, swollen tightness in your forearms. Often painful, somewhere on the scale from numbness to a severe ache, pump is often wrongly cited as being caused by lactic acid. The level of lactic acid is an index of muscle fatigue, but not really the cause of it. Rather, pump is caused by several changes going on simultaneously inside the forearm muscles as they try to cope with the demands of a sustained route.

Climbing is unusual in that it presents a local anaerobic endurance challenge, meaning that the centre of fatigue is in the small muscles of the forearm rather than being limited by the cardiovascular system as a whole.

"In most sports, anaerobic metabolism pathways are used, as metabolism is running too fast for the aerobic system to replenish energy. The nature of static contractions in the forearm muscle when we grip holds also limits aerobic metabolism by squeezing blood vessels shut under pressure, interrupting the supply of oxygen." - Dave Macleod, 9 out of 10 climbers make the same mistakes, 2010

It is these isometric contractions in the forearms - in which the contraction is held statically without the muscle changing in length - which are so significant in climbing. Contractions cause little or no blood to flow through blood vessels in the finger flexors, and chemicals struggle to exchange appropriately between blood vessels and muscles.

Here are ten tips to delay the dreaded pump...

1. Relax your grip!

First things first: the easiest step to delaying pump is to relax your grip. It may seem blatantly obvious, but people have a tendency to over-grip on holds, especially when anxious or if partial to a bit of bouldering. On longer routes, the moves are more sustained and don't always require one to "bear down" and crimp the living daylight out of the rock; rather you hold on as much as you need to without being so relaxed that you lose too much grip and fall off. A fine line indeed, but one which is often overstepped into clinging on - unneccessarily, hopefully - for dear life.

By over-gripping you are increasing and prolonging the static contraction of your over-worked forearm muscles, restricting blood flow and limiting chemical transfer - in other words, you will become fatigued fairly rapidly!

Instead of full-crimping - where you wrap your thumb over crimping fingers - can you half-crimp or open-hand the hold? Are you holding the best part of the hold and getting as many digits engaged as possible, or are you only employing two fingers in a pocket which could take three?

Tip: Practise at your local wall or crag when warming up on big holds - test how much grip and weighting of the holds is required on different terrain, and learn the most comfortable and efficient way to hold them.

2. Wrap holds

Following on nicely from the first tip, "wrapping" or "guppying" holds is an excellent way to cheat climb efficiently. It involves literally wrapping your fingers and palm around the side of a hold instead of grasping or crimping the hold straight-on. Imagine a sloth wrapping its claws around a tree. This method involves much less muscle contraction and can be surprisingly comfortable. Unfortunately there needs to be a particular profile to the hold - this isn't always possible on tiny edges and crimps, for instance, but handle-like jugs, slopers and anything with a protruding profile could be "wrappable."

A wrap or guppy can be a very useful rest position if combined with straight arms.

Tip: Practise wrapping holds you would normally use front on. Some holds will likely make you wrap instinctively, whereas others may take some thought and imagination!

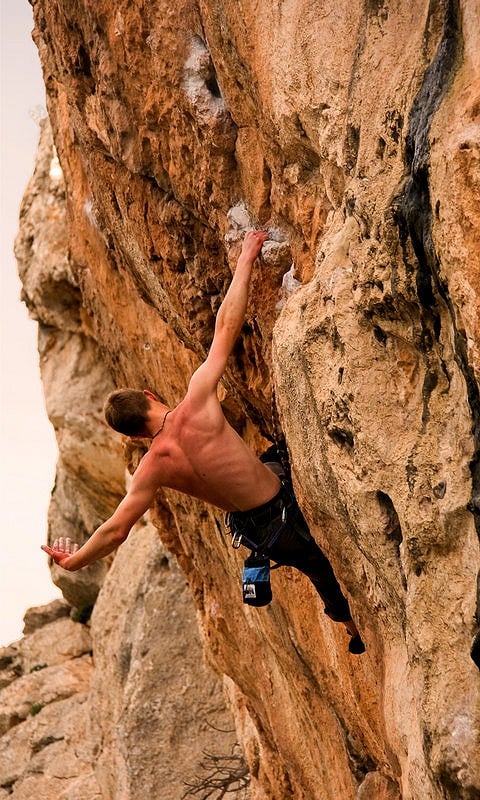

3. Straighten your arms

The old adage "Keep your arms straight!" was likely exclaimed by instructors and friends when first getting into climbing, yet often gets forgotten when arms get too strong, fatigue sets in or fear strikes and all good form goes out the window. By keeping your arms straight - in a similar vein (excuse the pun) to wrapping holds - your muscles are under less contraction, blood flow is less restricted and most of your bodyweight is resting on joints and the skeletal rather than muscular system.

In climbing, most of your body weight should be distributed through your legs, which contain much bigger muscle groups than your arms. On steep terrain, our body weight is being pulled down heavily onto our arms by gravity, so keeping our arms straight and our hips close in to the wall by tensing through the legs and core is the least we can do to relieve our arms of tension.

4. Shake it out

You may see climbers at the crag or wall frantically shaking their arms and hands, resembling something along the lines of the Royal Wave or a drunken rave, depending on the severity of pump. This is not a distress signal or cry for help, even though it could be argued as such, but rather the climber is attempting to relax the forearm muscles and get some oxygenated blood flowing into them.

As mentioned before, contracted muscle = restricted blood flow, so choose the biggest and most comfortable holds on the route, relax and straighten your arms and shoulders and give them a bit of a shake about one at a time to encourage blood flow.

There has been great debate as to whether you should shake your arms out below or above your head, with some arguing that by raising the arm, blood flow returning into the forearm upon lowering it again is increased. It really depends on what works for you, and as long as the muscle is relaxed, it's far better than still being tensed up on the wall in the first place. When trying to shake-out for the first time, it may seem to have little to no affect, but if you increase your endurance through climbing regularly, training and generally getting pumped (a necessary evil, unfortunately!) you will notice a greater capacity for getting rid of pump mid-climb.

You can also be tactical with your shake-outs: if you are feeling very fatigued and know that a hard move is coming up with a deep lock-off on your left arm, then making sure you spend a bit longer hanging on with your right and fully shaking-out your left might be a worthy sacrifice in the end. It can be hard to balance recovery equally on both arms, but when redpointing a project use knowledge of the sequence to your advantage.

It can also be helpful to briefly shake-out between individual moves with a quick flick of the wrist if you can feel a pump coming on. This can serve as a useful psychological aid, tricking you into feeling more recovered than you actually are.

Tip: When warming-down after a session, pick an easy route or make a traverse in which you do ten moves and then stop on a good hold and practice shaking-out, alternating arms and finding the best position for getting weight off the arm holding onto the wall.

5. Breathe!

Yet another one taken for granted - don't hold your breath constantly when climbing! Although occasionally useful for maintaining body tension and balance on hard moves, constantly puffing up like a blowfish and not breathing properly can have drastic affects on your performance. Again, it all comes down to respiration and replenishing oxygen supply to the muscles - if you're not breathing, you're not getting sufficient oxygen and your body is very much respiring anaerobically, even more so than usual.

Common tendency is to hyperventilate and take quick and shallow breaths when fatigued or anxious, which doesn't do much to help the situation. Relax, take slow, deep breaths in through the nose and out through your mouth. Focussing on breathing can be a great way of calming your nerves when fear sets in. Concentrate on lowering your heart rate by really focussing on calm, deep breaths.

When committing to a hard sequence - and in particular a dynamic move - expelling air from your lungs by power-screaming or simply exhaling can help both mentally and physically, by promoting explosivity and aggression.

Tip: Next time you're at the crag or wall, concentrate on over-emphasising your breathing (maybe make sure no-one is nearby...) and over time it will become more second-nature to keep a good rhythm in your breathing.

6. Route-read to find rests

Very few climbers other than competition climbers or serial redpointers bother to properly look at a route beforehand and work out a good sequence, rests, gear and clipping points. Even fewer route-read whilst en-route. By having a rough idea of the sequence and hold types before an onsight or a much more intimate knowledge of the moves when redpointing, you can improve your chance of success by finding rest positions.

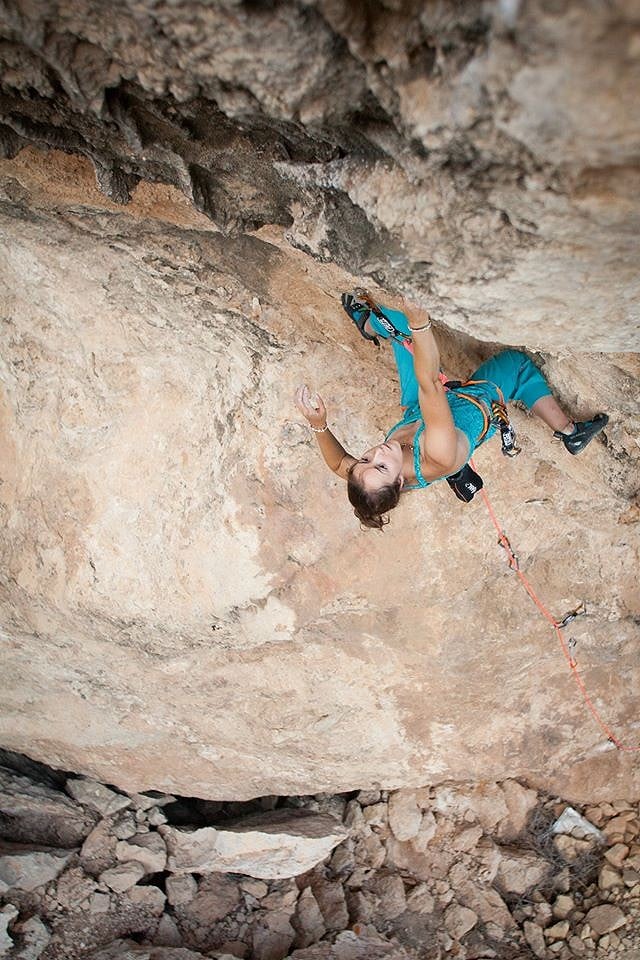

Look at the profile of the climb: Is it steep, vertical, slabby? Different angles will offer varying resting opportunities. A slab or off-vertical wall will offer no-hands rests, footplants and take most of the weight off your arms by their very inclined nature. If it's steep, can you find heel or toe hooks, knee bars and if you're really lucky - a bat hang?

More experienced climbers might find some tight Egyptians or 'drop-knees' which take the weight off your arms by keeping your hips into the wall and tensing your core and leg muscles. Dihedrals or corners offer ample opportunity for hand-free rests, just make sure your feet don't suffer for it instead. Aretes can offer great heel or toe hooks to gain a brief rest when in balance, and don't forget to "wrap" any holds you can manage, as mentioned above!

Whilst in the rest, take some time to look at the next few moves or the next gear placement. Kill two birds with one stone by resting and planning your next sequence in one fell swoop.

7. Pace your climbing: The Tortoise and The Hare

The best climbers don't climb overly fast or slow, rather they know how to pace their movement and exploit the nature of the climb. On slabby or vertical terrain, you have the luxury of taking your time, whereas on steep ground unfortunately this is not usually the case. Following on from above, pace also includes finding rests.

On easier sequences you can move as fast or as slow as you like, but as the holds get smaller and the moves get harder, moving swiftly and efficiently will prevent prolonged contraction of muscles on small holds, thus delaying pump.

That said, there is certainly no right or wrong when it comes to pace, and each individual will have their own style.

For some - our Tortoises - moving too quickly in the crux could ruin concentration and increase the risk of making a mistake. Hasty Hares will be more likely to be able to think fast and have more aggression in their climbing. Ultimately, it's a delicate balance. More cautious climbers may win the race, as long as they have the capability to keep holding on that bit longer and find rests.

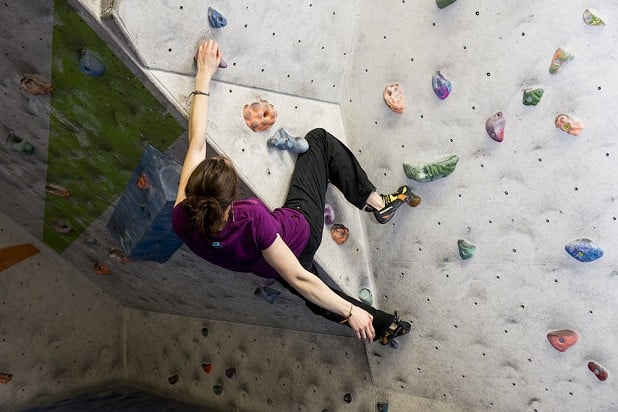

8. Refine your footwork: Point and Pivot

Sloppy footwork wastes time and energy: the longer you are hanging on trying to place your feet, the closer you are to the deadly pump. By placing your feet quickly and accurately you are setting yourself up for the next move with minimal fuss. Less experienced climbers have a tendency to clumsily place their feet on holds, rather than using the very tip of their shoe, they stand flatly on the ball of their foot or - even -worse - the arch of their foot.

The crisp edges at the tip of our climbing shoes are fantastic for pivoting on holds, enabling you to twist into the wall with your hips - gaining you reach and minimising pull on your arms. The tip of our toes offers more possibility for movement in different directions - like a ballet dancer can spin on her toes, so too can we as climbers. Try it yourself - it's usually easier to move into the position you need for the next move if you can pivot on a point, rather than trying to shift a larger surface area of rubber into the desired stance.

Tip: Take time to place your feet when learning good footwork and actively watch your foot go onto the hold, rather than looking up at the next move. "Climb like a ballerina" and try pointing your toes and using your shoe tips to help you move into positions.

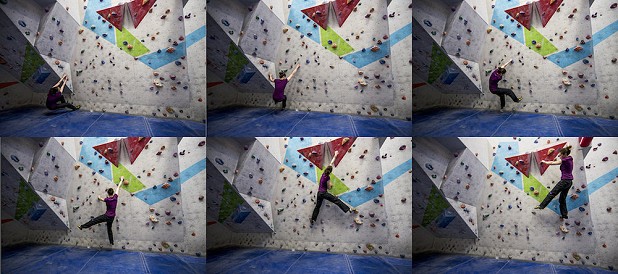

9. Use momentum - get into the swing of things

Pivoting through good foot placements brings us onto momentum. Momentum is a key concept in efficient climbing, in which kinetic or movement energy built up through a previous move transfers easily into the next move. By swinging between moves dynamically with straight arms, you reduce the amount of bent-arm muscle contractions and thereby the amount of time spent hanging on, as slow, static movement takes up much more time and energy.

Tip: Practice climbing more dynamically by swinging between holds (with feet still on!) and think of a route as a fluid sequence rather than as discreet movements – consider how the body position you’re in during one move will affect the next.

10. Clip early, clip late

Clipping positions when leading and placing gear on a trad route is often neglected or over-looked by many a climber. On a sport route or indoors, clipping the rope as soon as you can may feel the safest option, but it's not always the most efficient. Clearly it depends on the situation: if there is groundfall potential or no other option, then clip ASAP - but more often than not, that climber you see pulling up yards of slack with bent arms desperately reaching up for the quickdraw doesn't really need to clip from there. If she could climb a bit higher to a better jug slightly above the clip, this will save her bags of energy. It can be quite committing to bypass a strenuous but safer-seeming clip from below the quickdraw in favour of clipping from a better hold above, but you will thank yourself for it eventually.

The same goes if there is a jug below and at a stretch from the quickdraw and very poor holds and hard moves nearer and above it - use your common sense and choose the best holds and position to clip from.

When trad climbing a similar approach applies, although safety-wise you will likely be more limited as to where you can sensibly place gear from. Try to plan a few moves ahead from each comfortable position gained.

Tip: If in a roof or a position with the quickdraw below you, grab the quickdraw and clip it straight into the rope, rather than spending energy pulling up rope and fiddling with the quickdraw. This also saves faffing with a swinging, pendulum-like quickdraw!

Natalie is UKC's Assistant Editor and a 23 year-old climber based in Edinburgh with over 14 years of climbing experience. She is a former GB competition climber in Lead and Bouldering and has sport climbed up to 8b and trad climbed up to E4. Natalie has coached Junior GB Team members and adults looking to improve their grade over the last 5 years. She is sponsored by Mountain Equipment, Scarpa, and Lyon Equipment (Petzl, Beal) and is a Climbers Against Cancer and Urban Uprising Ambassador.

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

- ARTICLE: Alexandr Zakolodniy - A Climbing Hero of Ukraine 26 Apr, 2023

Comments