In this article UKC's Jack Geldard looks back ten years and more to his first adventures on the Lleyn Peninsula in North Wales. The quiet peninsula is a climbing back-water, oft over-shadowed by the mountains of Snowdonia or the easier to access and more solid Gogarth on Anglesey.

But for those looking for something to exercise the mind as well as the arms, then the Lleyn offers unparalleled opportunities for adventure climbing in a wild and serious setting.

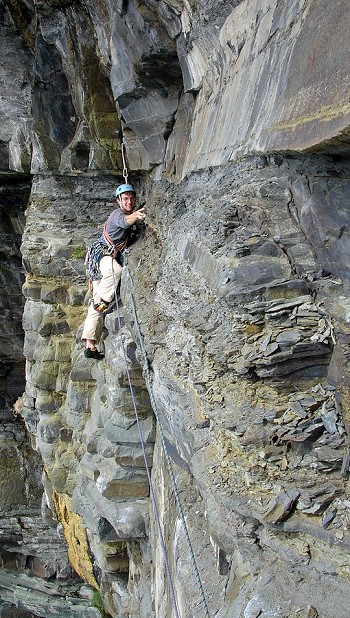

Byzantium (E4 6a) E4 6a, Craig Doris (FA Pat Littlejohn 1987)

My first experience of the delights to be found at the end of the Lleyn’s narrow, twisting, hedge-lined roads was at Craig Doris back in 2004. I found myself at the crag with a few rock stars, feeling, well feeling a little scared actually. Anyway, I think I got the honours of leading first and I don’t recall doing any more leading afterwards, but looking back I did have a nice day.

The route I led is one of the best in Wales and that of course includes Pembroke. Byzantium E4 6a, a Pat Littlejohn masterpiece first conceived in March 1987, a fine vintage for Lleyn sea cliff adventures and at the beginning of a trickle of hard new routes, that was to last for around a decade.

I started on the route with a slight sense of trepidation, climbing gingerly over what seemed like temporary rock and finding as much gear as I could ram in. It soon became apparent that the rock I was on, being quite solid in places (less so in others), gave climbing that was first class. After climbing a fantastic steep section on big breaks I found myself on the headwall with a slight pump and at the start of the crux - a perplexing boulder problem on solid rock. Above me a peg, just out of reach, sat rusting in a tiny crack.

In the van on the way down the country lanes, there had been talk of lassoing this peg before committing to the crux moves and also some talk of the peg having been removed and re-inserted at a more convenient angle to aid in this process. I didn’t know if this was true or even if it was at all possible, but it sounded good to me and I had my favourite 8ft sling to hand ‘just in case’.

As luck would have it, just as I was dilly-dallying around before the crux, contemplating how best to execute my ‘frig’ someone popped their head over the top to watch. It was none other than Pat Littlejohn. Oh shit.

With the sling idea now out of the question I faffed a little more and became quite vexed and probably a bit red in the face. The runners below me suddenly felt a long way down. Pat shouted down to my belayer, to see if I might like some advice. “Yes, gladly” I thought. “No” came the quick reply. Bugger.

In a wave of pride-saving inspiration I found the hold that unlocked the sequence and climbed to the top, quite glad that I hadn’t embarrassed myself and very pleased with what was an absolutely fantastic route.

Two years elapsed before I returned to the Lleyn, although I did find some rubble on the cliffs of North Devon. Dave Pickford dragged me to the Cheese-grater cliff on Baggy Point, armed with a selection of gate hinges for runners. It was to stand me in good stead for my next foray down on to the outrageous cliff of Cilan Main.

TerrorHawk (E6 6a) E6 6a, Cilan Main (FA Pat Littlejohn 1988)

In the summer of 2006 there was a slight lull in the run of good weather, routes in the Pass were damp and the sun only seemed to shine whilst I was trapped at work. Making plans in the pub is never a good idea, but that is where I agreed, after 3 pints of enthusiasm, to go and climb Terrorhawk on Cilan Main cliff with James McHaffie.

Having never been to Cilan Main before, I let James lead the way across steep angled fields whilst I gazed out to sea, following without paying much attention to where we were headed. It was a beautiful warm day and quite different to the mist of the mountains. The grass was dry which made the approach much easier, the soil is quite unstable after heavy rain and in some areas it is necessary to abseil down the field to get to the cliff edge.

We stopped a good twenty meters back from the edge and James started to get the abseil rope out of his bag. He shoved an end of it down a rabbit hole and pulled it up through the adjacent hole. We had arrived at the crag and this was our abseil anchor. Obviously I let James go down first.

I arrived on the wave-cut platform beneath the cliff to a jumble of broken boulders that had, at some point, made a similar journey to mine. What a rock face. The pillar we abseiled down was loose but gave amazing views across the main wall to our right as the crag swept around in an amphitheater of giant stacked blocks. Huge capping roofs bounded the cliff at two thirds height, and the walls below were steep and uncompromising. Luminous green moss oozed from crevices and white guano highlighted ledges and protrusions. I glanced back toward the abseil rope longingly.

The huge traversing line taken by Vulture (E4) was the only line of real weakness and it scuttled sideways for hundreds of feet to avoid the overhanging rock above. My mind tuned to Jack Street, the early pioneer of Cilan Main, who climbed Vulture in 1968, with just one peg for aid. The following description, taken from the history section of the ThrillSucker guide book, sheds some light on to the ascent. What a true adventurer and surely a climber right at the top of his game.

“We sorted out our gear and made our way across to the base of the cliff. Jack led off, geared up like a Christmas tree sending showers of rock debris down like dandruff. I crouched under an overhang wondering when the first runner would go in. At last one went in, only to be followed by complaints of ‘no good’, some grunts and then finally, the sound of a better one going in. There followed a period of silence, punctuated by falling rocks, and the rope ran out slowly until the clonking of doubtful pegs and a cry of ‘come on but don’t fall off’. I followed dubiously….. The position was now superb – above us a maze of overhangs blotted out the sun; below, the rock cut back in to the sea. Jack continued past, toe-traversing the thin slab behind me, and, despite my pleas carried on for 40ft to some obvious grooves, without placing a single runner. With some alarming looking bridging moves he crossed the grooves, and then, somewhat disturbed after the prize jug he had been heading for fell off on being touched, he swung clean out of sight….. Above us the clean cut groove jutted out alarmingly. After a few abortive attempts Jack cracked it using just 1 peg for aid at the top to swing right in to the final corner. I followed not daring to think of the consequences of falling off.”

C Jackson – Rocksport Dec 1968

James had climbed Vulture previously with Mark Reeves and Mark had warned me of the nature of the cliff. “It’s not somewhere you’d want to go twice” he’d said. I looked over at James who had come back for a second helping. I put my helmet on and felt a little better.

We roped up and decided who would lead which pitch and so forth. The route breaks down nicely for two climbers. It is 4 pitches in length and the technical grades steadily increase: 5b, 5c, 6a, 6a. After my thorough research I had secretly concluded that the final pitch would undoubtedly be the crux. This is the pitch that Pat Littlejohn inspected by abseil and also he placed a bolt on the belay before this pitch. Hence I drew my conclusions and made my plan. I’d try and give this pitch to James.

I muttered something about him having already done pitch 1, so it was only right that I did it this time. He bought it, so I racked up. I took pitches 1 and 3, James took pitches 2 and 4.

I must have looked nervous starting out, as James asked me if I’d climbed much on loose rock; a doubtful expression on his face. What a time to ask!

Slowly I wobbled up the first pitch with no runners that would hold a fall. James came up and met me on the stance and after a quick inspection of the wholly inadequate belay, he set off along the traverse of Vulture. This is where we were heading into new territory.

James set off along the foot ledge leading rightwards. It was from here that the long 4b traverse of Vulture weaved its way rightwards to the edge of the crag, away from the capping roofs and hanging corners. Our adventure was to take us straight up into this daunting maze of overhanging grooves.

A steep niche led upwards from the large horizontal band with powerful moves. Although James didn’t struggle I could see from the angle that the game had been raised. He disappeared from sight and the rope moved steadily up. The familiar shout of “Safe” eventually came, but it was followed slightly more quietly with “ish”.

I removed the belay carefully, so as not to break the bolt. The rock on Cilan Main is a bizarre mixture of grits (more solid) and shales (less solid). Luckily for us this steep section above the ledge was a grit band, with big layaway holds and a few flared cam runners. I arrived at the next traversing ledge pumped but alive and the rope lay limp, leading the way rightwards along the ledge. I followed it for fifty gearless feet quite glad that the climbing was only 4c in difficulty.

Above the next belay was a steep corner that allowed access through the aforementioned roofs. It had a few roof steps that looked tricky, but it also had a crack in the back. I was very relieved at the sight of that. The guide mentioned two peg runners so I was hoping for a safe but tricky corner.

The crack I’d seen from the belay was full of plants and mud and would take no gear. I spent a while scraping the crack with my nut key, desperate for a hold and with James’ encouraging voice egging me on I unearthed a fingertip side pull and finally committed to pulling around a roof on to the unseen headwall.

Hidden snappy crimps led me quickly, but very strenuously up the overhanging face to where the crack widened slightly. I tried to get a small wire in the crack, but it was just slightly flared and the stubborn nut refused to sit. I was now quite a long way up with no runners. I battled with the nut for what felt like an age, but it just wouldn’t go in. With the pump increasing I managed to bridge wide across the fragile corner and make some upward progress. It was harder than I had imagined and the fear was rapidly filling my forearms with lead.

At last the first peg came in to view and I hurriedly got a quickdraw through it and clipped the rope in. I felt a little better, but still couldn’t relax as the position was strenuous on the legs and fingers. The peg hadn’t aged well and didn’t fill me with confidence. Above, an un-climbable roof barred the way. Over on the right somewhere was the aid route of The Groove, I have a vague memory of spotting some pegs or bolts, but more pressing matters filled my thoughts.

Our route went left, across a steep overhanging wall to a flying arête, avoiding the huge rock ceiling. I would have to leave the safety of the corner and the old rusty peg. I was just able to hang on with my legs bridged really wide, taking some strain off my tired arms. I had to go for it right now or I would be testing this peg with all my weight.

Hurriedly I blasted all the way to the arête, where I looked for the second peg. It had rusted away to just a stub and was useless. Its rusty stain on the rock was the only way I was able to find it. I got stood in balance and placed an RP 0. The traverse continued for another twenty feet to the belay stance.

Here was the historical bolt placed by Pat Littlejohn and hammered flat on the second ascent by Crispin Waddy. Nearby a collection of peg eyes hung useless from a faded white bit of tat, the placements they once filled now choked up with rust. I got two wires behind the same loose block and reasoned that with the second peg gone on the pitch I led, if James were to fall off whilst traversing he’d take an 80 foot fall on to the poor belay.

I had a trick up my sleeve – a warthog, and with it I prized the mashed-up bolt hanger open enough to larks-foot a sling behind it. Phew. I hung limp from the anchors. James followed without falling and we both seemed pleased that we were still alive.

Perched high on one of the most inhospitable crags in the UK, with the sea crashing below us I realised how involved a retreat from this position would be. We had traversed out to the right of the cliff, directly over the sea. The route had overhung for 3 pitches and anchor placements for abseils were somewhat scarce. I dared not think about the long, dangerous jumar up the abseil rope. It was an amazing feeling, more akin to climbing in the Alps than to UK cragging.

Looking up at the final pitch it seemed a lot friendlier than the last. Damn, I had miscalculated and led the hardest pitch myself! As it turned out the climbing on the last pitch was certainly no push over, its agreeable first impression hiding some powerful and sustained moves. A long, overhanging lock-off between breaks on the lip of a roof was needed to start, with legs dangling useless above 300 ft of air. When I followed I was glad James had carried the heavy rack. I made the move, just, got established on some better holds, and started removing the first runners, safe with the protection given by a rope from above.

Steep, pumpy climbing interspersed with cam runners led to the grassy top. I reveled in the position, reasoning that James must have a sound belay as he had topped out and could ferret around in the rocks above. Mentally relieved but with hands opening due to sheer exhaustion, I finally hauled myself, totally spent and covered in guano, but smiling, over the lip. We’d made it back on to Terra Firma.

As the summer kicks in ten years after my ascent of Terrahawk, I’m looking forward to spending more time in Wales. I don’t know if I’ll venture down to the Lleyn this year, but if I do then this time I’ll make damn sure James gets the crux pitch!

See you there.

Jack Geldard is a consulting editor at UKClimbing.com. He also works as a climbing instructor and coach, holding the Mountain Instructor Award. He is also a trainee British Mountain Guide.

He has climbed in 5 of the 7 continents, up to a very high level, and enjoys all forms of climbing, from winter alpinism through to summer bouldering. He's still not overly keen on falling off though...

His particular favourite styles of climbing are UK seacliffs, classic Alpinism, and multipitch sport climbs. Or pretty much anywhere sunny.

- He's available for Instruction, Guiding and Coaching in North Wales this summer.

- You can read a little more about him on his own website: Jackgeldard.com

More Articles

Comments