This essay, by Paul Hill MBE, Professor of Photography, is part of the foreword to Henry Iddon's (UKClimbing.com profile and Photo Gallery) book Spots of Time, The Lake District photographed by night, published by the Wordsworth Trust on the occaision of the exhibition Spots of Time, 16 March 2008, in an edition of 800 copies. Website: www.spots-of-time.co.uk

Spots of Time, the exhibition, is running at The Trust's 3°W Gallery, at Dove Cottage, Grasmere, until September 2008 and it is FREE to visit. Details at this page Wordsworth Trust. The Wordsworth Trust is ideally situated to visit when on a climbing trip to the Lake District.

You can read Spots of Time: the experience by Henry Iddon, here at UKClimbing.com.

The silence that is in the starry sky

The sleep that is among the lonely hills(1)

William Wordsworth (1770–1850)

Natural Magic and Moonlight by Paul Hill

I was disappointed, and not a little bewildered, when looking at the publications that accompanied two of the major events in photography during 2007 – the How We Are exhibition at Tate Britain, London and the flagship series on BBC 4 (repeated on BBC 2), The Genius of Photography – to discover how little nature and our natural landscape featured in both. There were fine examples of how man has industrialised or commodified them – a predictable urban view – but little or nothing on them as subjects of awe, meditation, or (whisper it quietly) aesthetic pleasure. British Romanticism with its radical expression of freedom and new ways of perceiving the world, permeated with idiosyncrasy and joie de vivre, was noticeable by its absence.Of course, exhibitions and television programmes are curators' and directors' mediums, and we can invent all sorts of reasons why particular covert agendas may have dictated their content and treatment. Just because they do not reflect our perspectives on the subject matter, does not mean that they do not have a great deal to commend them. It is not censorship by omission, or lack of scholarship, it is more likely to be that certain types of photography are not fashionable. They may have been practised extensively, but certain ones are invisible to those who do not wish to see.

Photographic genres, like documentary and portraiture, are now frequently replicated, reconstructed and reinvented as expensive art works. A style or a particular historic icon is usually the inspiration, which, of course, presumes we realise the significance of what is being appropriated and painstakingly re-enacted. The source is photographs rather than direct human experience, and the engagement is with the discourse rather than the real world. Many contemporary art practitioners see Landscape Photography as a traditional genre ripe for revisiting, via table-top or photoshop reconstructions so beloved by Postmodernists, rather than by engaging with the place where the photographer is making the picture (the stuff under his/her feet), and his/her personal feelings and attitude towards it.

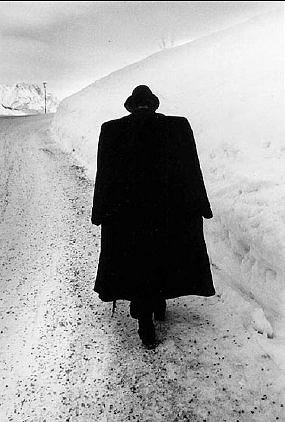

Henry Iddon's practice foregrounds his involvement with the world and he transports us to vantage points that we may never reach and surprises us with aspects we may never see at first hand. In Spots of Time, he is a seeker after beauty, and also our guide (see his website, www.spots-of-time.co.uk, 2), who extended himself physically (he climbed 53 fell summits for this project and camped out for 19 nights, often in freezing conditions, and spent in total 44 moon lit days and nights on the mountains), and used his extensive photographic experience and intuition to imagine the aesthetic outcome of what were visually speculative nocturnal expeditions. This inevitably unpredictable exercise is a recurring feature of photography, where things never quite turn out the way you expected, or hoped for.

Through trial and error, a good grasp of optics and chemistry, and great persistence, William Henry Fox Talbot (1800 – 1877) evolved a process that used a camera to capture a latent image; that in turn became the negative, which was then placed in contact with another piece of paper to produce an image, the positive. This was only made possible through alchemy, or what Talbot, in 1839, called 'natural magic'.

The most transitory of things, a shadow, the proverbial emblem

of all that is fleeting and momentary, may be fettered

by the spells of our 'natural magic', and may be fixed forever

in the position which it seemed only destined for a single instant to occupy.(3)

The negative/positive process formed the basis of all photographic practice for the next 150 years until the recent digital revolution came along. It is, of course, still used today to produce billions of photographs every year.

Like Iddon, Talbot was fascinated with the process of making photographs by the light of the moon. In a letter written in the same year as he registered his discovery (1839), he wrote:

I believe I told you my paper is sensitive to moon light, it takes

10 minutes to obtain a visible impression.(4)

Like most Victorian aesthetes, he was attracted to ruins and made 'a view of ruins by moonlight' in the same year. These nocturnal experiments were also undertaken to prove that Talbot's materials were more sensitive to light than the French Daguerrotype.

I am sensitive to simple moonlight . . . I throw out as a challenge

to all photographers of the present day: viz. that I grow dark in

the moonlight before they do.(5)

Talbot was part of a well-educated milieu that had witnessed great advances in the arts and sciences in the late 18th, and early 19th centuries, and he had become particularly enamoured with natural philosophy, alchemy, and Romanticism.

He would know that the painter Joseph Wright of Derby (1734 – 1797), a pioneer, reflected the Enlightenment in his paintings of scientific experiments (e.g. A Philosopher lecturing on the Orrery, 1766, and The Alchymist, 1771) and presaged British Romanticism in art through his evocative landscapes that influenced Constable and Turner, who followed him. Landscape painting in the 18th century held a very lowly position in the fine arts, as it 'did not improve the mind . . . nor inspire noble sentiments', a critic wrote at the time. Despite this indifference Wright diligently explored how his paintings could celebrate this ' inferior' subject matter and grappled with the best way to render the effects of light, form and texture in oils.

Wright was also as enthusiastic about the Lake District as he was about his own Derbyshire Peak District, describing the area as having

. . . the most stupendous scenes I have ever beheld . . .

they are to the eye what Handel's choruses are to the ear.(6)

It is fitting that Wright's last oil painting, Ullswater (1794 – 5), hangs in the Wordsworth Museum in Grasmere, the home of British Romanticism, and has always seemed to me to be suffused with a quality of light that could only come from the moon.

Henry Iddon's photographs are, for me, much more than mere visual representations of what is in front of the camera, they are mysterious manifestations of 'natural magic', as Fox Talbot put it. We know that a stage magician uses mechanics and guile when he saws his assistant in half or pulls a rabbit out of a top hat, but that does not destroy the moment of surprise or wonder. The finest exponents of illusion take us into another dimension that subverts the rational and transports us to a world where things are not quite what we are told they should be. Surely the truthful photographic record produced by a camera canot be an illusion, you might think? Yes, it is!

Iddon is not driven by a search for some objective 'truth', art historical references, or reconstructions of past genres, he is obsessed with light and time (he made, on average, exposures of 90 seconds duration) to discover what things look like when photographed. He is a follower of a photographic tradition that respects the subject matter's cultural and aesthetic resonance as well as the unique characteristics of the medium. His methods are, on the surface, simple and direct, but the results are a compelling mixture of subtlety and surprise. The light of the moon gives each image a serene luminescence like bright daylight until we spot the sinister orange glow on the horizon or, in another picture, the strange floating 'ribbon' of white in the valley. This illuminating inversion is complex and intriguing, but a natural outcome of the methodologies he has used. The subject matter, in this respect, has become the medium, not the mountains. There has been no need to experiment by means of self-conscious or artful interventions. He has employed photo-graphic seeing, that unique transformatory mystery tour that frustrates directorial control, encourages the unexpected and accidental, and often results in new visual experiences that engender a sense of wonder and spiritual elevation that is parallel, and equivalent to 'being there', inwardly as well as outwardly. Like Wordsworth, whose poetry strove to transform everyday reality and to describe a mystical union of man with nature, Iddon's vision revises the way we perceive these mountains, fells and lakes, and our place in this environment.

Alfred Stieglitz (1864 –1946), the New York photographer and gallery owner who, almost single-handedly, introduced modern artists, like Cezanne, Braque, Picasso and Brancusi to America in the early 20th century, was also a champion of the art of photography.

Stieglitz was very glad to have these things (in his gallery) because he found that this art was being trampled on in the same way that photography was.(7)

Paul Strand, photographer and film-maker

Stieglitz famously made Equivalents: photographs of clouds, hills, trees, grasses that were meant to evoke experiences and feelings in a manner comparable to music. This approach influenced subsequent generations of photographers who believed a photograph could be more that just a representation of what was in front of the camera. It seems to me that this attempt to forge new ways of seeing and reflecting upon nature and natural phenomena connects the likes of Wright, Wordsworth, Talbot, Stieglitz, and Iddon, despite the vastly different eras and cultures they represent.

For us, the viewers, these photographs are the experience and the event. Iddon presents us with two dimensional colourful approximations of what he framed and captured which, in turn, were created by the action of light emanating from the heat of the sun (caused by nuclear fusion), reflected off the surface of the moon, then the land around him, through the carefully positioned lens and, finally, onto light sensitive material in the camera, which is anchored to the ground by a firmly planted tripod. But is there more to it than that? Where is the Art? The quest for an acceptable definition of Art will only lead us into a philosophical tar pit, so let us examine the application of photography that does not seek to illustrate text, or sell merchandise. Photography for its own sake, if you like.

Iddon knows his tools, and their creative potential, as much as a painter or sculptor does. The tactile aspects inherent in the use of brush or chisel, pencil or blowtorch may be absent, but these are surely only agents used by the maker to transform one thing into another. Paint, carve, draw, weld – photograph. What matters is the skill and imagination applied to the task – the magic.

I think one's sense of appearance is assaulted all the time by

photography . . . 99% of the time I find that photographs are

very much more interesting than either abstract or figurative

painting. I've always been haunted by them.(8)

Francis Bacon, painter

The camera can anchor us to a specific place, or, to an idea, which enables us to explore, observe, and re-present both the external world and our internal reactions to it. So why is it that most camera owners seem to select the same 'scenes' – waterfalls, sunsets, towering mountains, and sylvan glades? This is not just a predictable attempt to imitate 'good' practice, as described in the newly acquired instruction manual, it goes back to another earlier type of manual – the 19th century guide books for travellers seeking uplifting 'views' from accessible vantage points. The text of these guides may not have been poetry, but they would have been influenced by the ideals of Romanticism, and aimed to elevate and educate the curious traveller. It would not be long before the practitioners of the new medium of photography came to try and capture those 'views', and visually match the writer's descriptive prose.

These photographic scenes were first recorded for the aesthetic pleasure of the better off and educated sector of British society – they were the only people who could afford the expensive photographic equipment – and most were kept in albums, not dissimilar to those in most households today that contain the holiday photographs. Enterprising and commercially-minded photographers – tradesmen, as opposed to artists – recognised that very few of the ever-expanding number of Victorian tourists who were taking advantage of the new railway system and increased leisure would have the time, or inclination, to find the 'views' for themselves, or possess the necessary skills or resources to make photographs. But they were still keen to buy realistic likenesses to take home in order to re-live the experience of the visits, or to impress their family and friends.

With the greater access to, and appreciation of, natural landscapes, these new, largely urban-based, cultured travellers realised that it was important to conserve these rural areas for their aesthetic enjoyment, and to help convert others to the cause; and the medium of photography was used to this end. It can be argued that this was not so much about conservation as preservation, aimed at creating rural enclaves for those opposed to the seemingly soulless march of industrialisation. But industrial progress brought with it roll film and lightweight cameras, motorised transport, and paid holidays, and the unspoilt countryside was no longer just a playground for the well-heeled classes. Contact with Arcadia became available to all. Half the population of Britain lives within one hour's drive of the borders of the first national park in this country – the Peak District National Park (established in 1951, the same year as the Lake District). I live only one mile away from it. Tourism is our area's biggest employer and reliant on the partial and persuasive use of photography to attract visitors in order to maintain economic stability for the inhabitants of this rural community. Whilst enjoying being amongst the hills and dales visitors indulge in the largest creative pastime in the world – photography. And they nearly always attempt to re-create the images that persuaded them to visit the area in the first place. To do 'something different' is rarely a considered option. Why? Just look at the photographic magazines at your newsagents. They all carry articles offering advice on how to make 'good' landscape photographs ('scapes') with illustrations that are so similar, they could all have been made by the same photographer.

To make a replica of something we believe, or are told, has quality, gives us a sense of achievement. This is relatively easy nowadays as digital cameras have virtually deskilled photography, with programmes for almost every contingency, including a 'scene mode', believe it, or not. What more can the medium offer than affirmation to the hobbyist – and even many professionals - that you too can produce an 'accredited' photograph? But photography can offer so much more, even to the novice, than that.

Photography can be a formidable tool of investigation for the curious and adventuresome as it offers firsthand experience of the many mysteries around us: the mysteries of nature and society – and of our own selves. It combines the real world and the world of the imagination

There are a large body of photographers who wish to follow the subjective pathway, believing that they can reveal, through photography, or camera vision, the otherness of existence – the spirit, or essence. They quite often use the landscape as their motif. Other expressionistic photographers create metaphors through photographing – usually in a particularly individual way – seemingly ordinary subject matter, which may be meant to be imbued with significance, and can even be interpreted as having deep psychological meaning. It may be invidious to attribute any objective significance to the physical subject matter in such personally expressive photographs, as the aim is metaphysical. The ambition is to make work that only uses the real world as the starting point and to end up with images that transcend the physical nature of things.

Our social, educational and cultural background establishes our visual literacy and how we interpret photographs. We inevitably see in them what we want to see. In my opinion, the majority of landscape photographs I see rarely challenge or surprise. They are predictable and formulaic and pose few philosophical or visual questions. They are conservative artefacts celebrating the status quo. This will not worry weekend painters or amateur photographers, but is anathema to the avant-garde artist or photographer who strives to offer new perspectives on familiar subject matter. If Iddon's images reflect the pursuit of beauty and the aesthetic experience, as I assert, it may be necessary to ascertain what is meant by these descriptions. Does 'beautiful' imply a sense of harmony between various elements, a soothing sensation, or a gut feeling? Or has the word become like 'nice', a bit anodyne and imprecise, rather than referring to something full and resonant of 'beauty'?

In all our judgements by which we describe anything as

beautiful we tolerate no one else being of a different opinion,

and in taking up this position we do not rest our judgement

upon concepts but only on our feeling. We therefore base them

on feeling not as a private feeling but as a common sense.(9)

Emmanuel Kant, Critique of Judgement (1790)

The use of 'common sense' seems dogmatic, but Kant meant that an apprehension of beauty does not vary from person to person like sensory pleasure or desire, but is uniform and constant. As Harold Osborne wrote in his book Aesthetics and Art Theory(1968):

When we are aware that something is particularly well

adapted to our powers of perceptive awareness, apart from

any reasoning about it or any intellectual analysis, we

enjoy an aesthetic experience and call that thing beautiful.(10)

He later added when referring to the autonomy of the art work that:

. . . the most distinctive feature of practical aesthetic attitudes

today has been the concentration of attention on the work of

art as a thing in its own right.... not an instrument made

to further purposes which could be equally promoted

otherwise than by art objects.(11)

Iddon's images, by these 'definitions' do give us an aesthetic experience and they can be described as beautiful.

Most importantly this work offers a new perspective on a familiar photographic genre. He has garnered light, upon which all human-life depends, and he has used time, not instant-aneously, but with necessary longueur, to produce still, timeless images.

This is a celebratory and colourful vision of the Lake District that has never been seen before, and which cannot be created other than through first-hand experience and by that most accessible and ubiquitous of mediums – photography, or 'natural magic'.

NOTES

1. William Wordsworth, 'Song at the Feast of Brougham Castle' Composed 1807, published in Poems in Two Volumes 1807

2. www.spots-of-time.co.uk

3. W. H. Fox Talbot Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing by which Natural Objects may be made to Delineate Themselves without the aid of the Artist's Pencil, London 1839

4. W. H. Fox Talbot letter to J.W. Lubbock, 3rd November, 1839

(www.foxtalbot.dmu.ac.uk)

5. W. H. Fox Talbot letter to J.F.W. Herschel, 1st July 1841 (www.foxtalbot.dmu.ac.uk). This is a reference to the rivalry between Talbot and the daguerreotypist, A. F. J. Claudet (1797–1867). He was

a French-born scientist and photographer based in London who used certain chemical methods to improve the sensitivity of his daguerreotype

plates and to shorten the exposure times. He had not at this time shown

that his process could register moonlight. Talbot's calotype process was a rival method, which had been able to make photographs by the light of the moon. Light registers as 'dark' on a negative.

6. Joseph Wright letter to Richard Wright, 22nd August 1794 (Jane Wallis Joseph Wright of Derby, Derby 1997)

7. Paul Hill and Thomas Cooper, Dialogue with Photography, Stockport 2005

8. David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, London 1987

9. Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Judgement (translated by J.C. Meredith, Oxford 1928)

10. Harold Osborne, Aesthetics and Art Theory, London 1968

11. Ibid

© Paul Hill 2008

See the best landscape photography at UKClimbing.com by clicking here here

See the best landscape photography at UKClimbing.com by clicking here here

RELATED ARTICLES

Better Mountain Photography by Sean Kelly

How to get the best out of your camera in the Mountains by Jon Griffith

The Digital Darkroom: photos before and after by Nick Smith - UKC

Comments