Overdoses are strange things. Their effects don't necessarily show up where you'd expect, at the point of impact. Take 360 Paracetomol, and if you don't reach hospital in time, then it doesn't matter that they can pump your stomach cleaner than an operating room. Your liver will be shot, and you'll die a few days later, painfully. Similarly for cocaine: stick enough up your nose, and it's your heart that'll give out.

Getting the climbing habit is a gradual process. You start out on nice, safe things, HSs and VSs, and when you see people climbing what seem to you outrageous routes you think, "That'll never be me, I'll never get like that." Then before you know it you're talking to someone in a shady part of the crag, and they're saying, "You want to do some Es? We'll use my gear..." and you look from your cowbell Hexes to their rack and they have these hypodermic-thin things such as RPs.

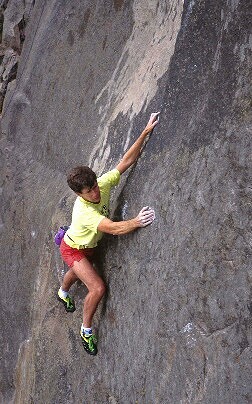

What strange stuff gravity is. You are fractionally lighter when you stand at the foot of a mountain or even a crag than on flat ground: the rock's mass generates its own minuscule pull, urging you upward, a subconscious song your ears might feel but never hear. You follow the call upwards. And you're hooked. Just like any drug, it can make you forget pain (or can inflict it). It can make you ignore other, more important things in order to experience it, and tempt you into selfishness, spending money and time on yourself rather than other people and things. "You're all mad," snaps my (non-climbing) girlfriend tearfully, and stalks away. [Er, now long-since ex-girlfriend - CA] To which I can only reply: not mad, addicted. There are heroin addicts who hold down full-time jobs, lead middle-class lives. They aren't mad. Few addicts are; feeding a habit takes too much discipline. Then you start soloing. That's when you realise what it is to really load up the syringe with gravity and hold it poised to take a hit. Like any junkie, you tell yourself you're in control. You're only doing the safe things. You're only using "soft" gravity, the one that lets you feel yourself pulling on handholds, tugs at your feet on the footholds, gives that delicious feeling when you smear and the friction between your boots and the rock overcomes your weight. You're not on the hard stuff, oh no, not that concentrated gravity which will accelerate you faster than any car, 0-60mph in under three seconds, but without brakes...

So there I was, 30' up, revelling in the gentle stuff, when I got it wrong.

At this point, the world splits neatly into two groups: the non-climbers, who ask "Why didn't you have a rope?" and the climbers, who ask "What route were you on?" Well, it was an on-sight attempt on Great Slab at Froggatt: unprotectable E3 5b. Those who know it then ask: "Which move?" The crux traverse, a rightward step across and slightly down. I half-started it, retreated, considered wailing for a top-rope, then went for it. Wrongly, as it turned out.

Falling from that height, you get a brief time to think. It being my first introduction to a substantial decking, my thought was: "Hmm. This will be interesting." I landed on my feet, bounced back and hit a boulder with my bum (producing a bruise the size of Rutland). Some people say pain explodes, but not really; more like turning on a light. Click. Pain! In my back, my back. I can feel my feet, my toes, everything - so my spine's not bust, I managed to think - but most of all there was PAIN.

I don't recommend having an accident. If you do it somewhere busy, as I did, then you do meet a lot of new people very quickly. But it's like being at a party where no one has brought any drinks and there's no music and there's only one topic of conversation - your injuries - which you have to recycle endlessly. How did you land? What did you hit? What hurts? Does it hurt more or less now? Eventually, as at any good party, someone turns up with some drugs. "Hello Charles, I'm Keith from the Derbyshire Ambulance Service, if you want then take a deep breath of this." So it's only nitrous oxide, but don't laugh it off. At least it dims the blinding searchlight of pain. And the Mountain Rescue turn up, always a relief, like the blokes who turn up with fresh booze just when the party is running down. Then you're moving, and you're in an ambulance, and you reflect that for some climbers this is their last journey, their last hit of gravity. Not a nice thought. Time for some more gas.

In the hospital they take pictures of your ghost. "You've got what we call a compression fracture in your back," says the doctor. On impact, all your vertebrae cram together like a pack of cards being riffled. The further down your back, the more cards on top, the more weight to bear. Eventually one cracks under the strain, a bright white line showing up in my ghost's picture, pointing down to the source of the trouble: my overdose of gravity. Taken through my feet, its effects showed up far away. The cure: two weeks' cold turkey, laid flat out on your back.

After that, you're gradually re-introduced to the cause of the trouble. After a week they tip your bed slightly; after another they sit you upright. Those first moments back in the vertical are like your first cigarette or joint: your head swims and keeps swirling even after you close your eyes. You're reminded how high your tolerance was: just two weeks ago being 30' up on a foot and a hand was fine, and now your feet are an inch off the floor and you don't trust yourself to stand. But soon you're walking and climbing stairs. Again the world splits into non-climbers and climbers: the first lot ask, "You're not going to do it any more, are you?" and the others ask "Will you be OK to climb?" It takes a junkie to know one. Unfortunately, you tend not to give up a drug just because you got the amount wrong once. But you are more careful how you measure your hits. I think, next time, I will take a rope.

(* note: this article first appeared in On The Edge's Back Passage slot. The accident was in 1995 - I'm fine now, thanks. I did go back.. but with a (top)rope. Special thanks to the Edale Mountain Rescue Team and the very patient nurses at the Sheffield Hallamshire, who helped me get over my overdose. - CA)

Comments