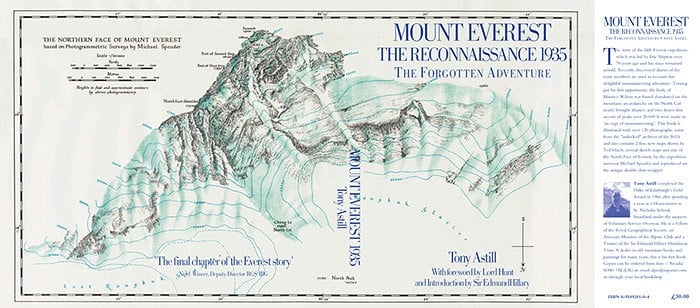

Does the title of this book sign its own death warrant? A forgotten adventure, a reconnaissance, undertaken over 70 years ago. Well hopefully not. It is superbly produced, with over 350 pages, 125 atmospheric and well reproduced photos (all in black and white, the only colour film shot was sadly lost) and nine maps three of which fold out. The unique double dust jacket seems a bit gimmicky, but that is only a quibble.

The dust jacket states that the adventure is previously untold. Eric Shipton the leader devotes a mere 12 page chapter to it in his memoir Upon That Mountain published in 1943; albeit with meanderings into expedition food in general and the best time to climb in the Himalaya. History did indeed seem to have passed it by.

Of the six pre-war British Everest expeditions this was the only one never documented in its own book, this alone justifies its writing, since the eventual ascent in 1953 was on the shoulders of previous attempts, and the inclusion of the New Zealander Dan Bryant in 1935 lead indirectly to Hillary's inclusion in 1953. Tenzing Norgay also makes his first appearance as an inexperienced 19 year old.

The narrative is almost entirely structured from the expedition diaries and letters of the seven team members, six climbers and the surveyor Michael Spender, brother of the poet. This is both the books strength and its weakness. The wealth of detail of exact daily happenings, meals consumed, letters received from home etc. is staggering (a typical Tilman entry of his daily food intake: “4 oz milk, 4 oz biscuit and satu, 4 oz pemmy, 2 oz cheese, 4 oz sugar. Total = 18 oz.)” Tilman's cooking, apart from his bread making seems widely unappreciated.

No headache is left unrecorded, Dan Bryant who although a strong climber never acclimatised well enough to be invited the following year on Ruttledge's 1936 expedition “felt A1 and hoped he had got over the worst of his altitude troubles, although he redeveloped a headache in the evening and did not eat much” – clearly a short lived burst of optimism.

Shipton at one point does suggest that the expedition members are not eating enough – partly a result of his Spartan dietary philosophy no doubt, however the consumption of sufficient fluids now regarded as so essential at altitude is scarcely mentioned, a cup of cocoa at bedtime is deemed noteworthy. This cannot have helped some of the acclimatisation problems.

The expedition was granted access by Tibet too late to be anything other than a small-scale reconnaissance. By the time Everest base camp is reached in July the monsoon has started. We may now take it for granted that the best season is post-winter and pre-monsoon but this was not so certain in 1935. In fact the struggle to reach the North Col proved that the snow was generally too deep and dangerous by that time of year and future expeditions planned accordingly.

The body of Maurice Wilson is discovered. He had died making an eccentric solo attempt the year before, despite having no mountaineering experience. Interestingly two of the Sherpas who accompanied him are also on the 1935 expedition.

After retreating from Everest itself, the team members enjoy an “orgy” of summit bagging – 26 peaks over 20,000 ft including 24 first ascents, the highest being 23,640 ft, Dan Bryant finally makes some sort of acclimatisation.

The book illustrates superbly Shipton's philosophy of small lightweight expeditions, buying local produce where possible - mainly sheep and eggs; at one point four members are said to have consumed 120 eggs in a day, no diary records the effect on their bowel movements of this eccentric diet. This does not prevent them gorging on the spoils of food discovered from the more luxurious 1933 expedition and here Spender does document an attack of dysentery when accepting a piece of chocolate from a Sherpa already infected “so as not to hurt his feeling” a high price for courtesy.

Some diary entries do make mild criticisms of Shipton's leadership, but on the whole the entire trip comes across as remarkably harmonious. The members are often split into two parties, with separate objectives; much time is spent on surveying and supporting Spender. Reconnaissance, map making and exploration are as important as climbing which may surprise those of us brought up on a diet of the post-war expedition book.

Already in 1935 you can see Shipton signing his own death warrant, which lead to his ousting as leader of the 1953 expedition in favour of John Hunt. He just did not like large expeditions, and the attainment of the summit was not his sole purpose in going to remote places.

The photos are excellent. They give a feel to the time, the primitive equipment and clothing, the river crossings, handing out cigarettes to Sherpas, the first picture taken of the Western Cwm.

Tony Astill has done a remarkable job. He has sifted through the material to make a coherent narrative of an important historic expedition. There is no cutting of corners; so many modern expedition books have too few photos; many lack an index. It has clearly taken many years; Lord Hunt supplies a foreword written in 1998 shortly before his death, in which he praises Shipton's gifts.

Was writing it worthwhile? What one person regards as a definitive account another may see as over detailed and repetitive. To the armchair mountaineer who religiously buys the latest Bonington book it may lack a thrilling climax, but it deserves a place in the narrative of Everest's history, just don't expect “Into Thin Air”

Comments