He also climbed with my father, Mike James, in 1961, when he joined Mike and his four British climbing colleagues on an ascent of the Piz Badile - a story retold here - "I can understand how he survived so long on the Eiger, and how he led the party the whole time, for his strength and determination are great, especially in difficulties." says Mike in this article.

In May 2008 we published another related article by Kate Cooper The Eiger Nordwand Revealed: Rainer Rettner Interview about Rettner's book 'Eiger - Triumphe und Tragödien 1932 – 1938'

In the following article, frequent UKC contributor Luca Signorelli gives his personal account of the life of Claudio Corti, a life that became entirely dominated by the epic on the Eiger.

Alan James

In 2004, the Italian Alpine Club acknowledged the 'official' version of the first ascent of K2, recognising Walter Bonatti's crucial role in providing Compagnoni and Lacedelli with the all important oxygen they used to reach the summit. For Bonatti this was a personal triumph, as he had struggled for more than 50 years to see his version of the 1954 ascent being recognised as the truth.

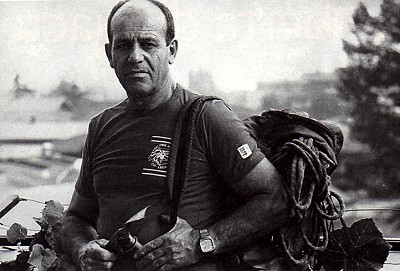

After a press conference in Lecco, Italy's most climbing-obsessed town, Bonatti saw an old friend in the crowd: Claudio Corti, known in all Lecco as 'Il Marna', who had made the headlines in the late 50's because of his dramatic rescue on the North Face of Eiger, and the polemics and controversy that had followed. Bonatti (who knew Corti well, and had always been very supportive) approached him, “You know Claudio, now we should really do something for YOUR story”. Corti shrugged and smiled, “I don't care. It's all past now.”

As Claudio Corti died on February 3rd, 2010 in his home of Olginate, Italy, we will never know if the Eiger ever really “passed” for him. Some people, among them Corti's biographer Giorgio Spreafico, think he never escaped the consequences of those tragic nine days on Swiss Oberland's most famous mountain, and all the years of controversy, accusations and desperation. He dubbed Corti 'The Prisoner of Eiger', but it would be sad to think of him in just that way. 'Marna's' climbing career was rich and adventurous, and covered such diverse terrains as Western Alps, Bregaglia, Dolomites and even Africa and Patagonia. In different circumstances, he could have been remembered as one of the best of the 'Ragni di Lecco'- the elite group built around the stars of Lecco climbing scene, one of Europe's most prestigious.

But a large part of Corti's life was defined, changed, and possibly ruined by that single event. Even more than Edward Whymper, whose existence was transformed by the Matterhorn accident in 1865, Claudio Corti's life changed for ever on a late afternoon of August 1957, when he reached the summit of Eiger, carried on the shoulders of Alfred Hellepart. The aftermath of that event, and the distorted interpretation given by the press, overshadowed the 'real' Claudio Corti, much like the fictional Whymper of the post-Matterhorn controversy overshadowed the real Whymper of 'Scrambles in the Alps'.

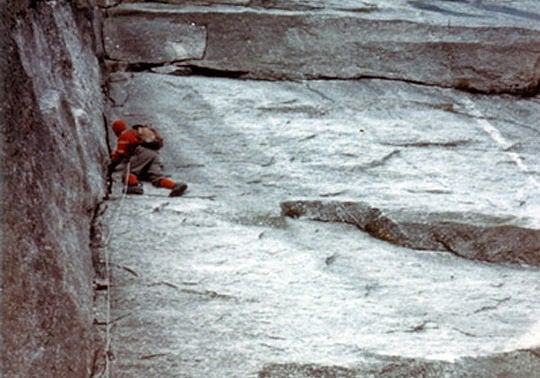

For 6 days Corti and his friend and climbing partner Stefano Longhi had battled their way up the Eiger North Face - the World's most famous alpine wall - hoping to be the first Italians to complete the ascent of the 1938 Heckmair route. The Italians had met two brilliant German climbers, Gunther Nothdurft and Franz Mayer halfway up the face and together, both parties had experienced a terrible amount of bad luck. Nothdurft had fallen ill, Longhi became increasingly tired and frostbitten, the weather had turned bad, the climbing conditions desperate, but the foursome still pushed on, knowing that their only way out was the way up. Then Longhi fell from a ledge above the Traverse of the Gods, and because of frostbite and exhaustion he could not rejoin the others who were forced to abandon him and go in search of rescue.

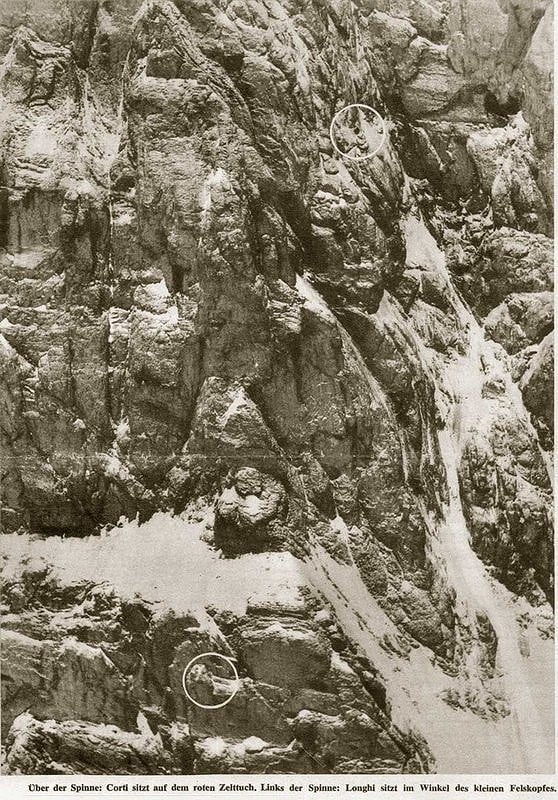

Shortly afterwards, Corti had been put out of action by a falling stone. Nothdurft and Mayer, who needed to move fast and light to have any chance to summit and descend alive, left Corti their bivouac equipment (including the red tent), while Corti gave his climbing gear to the Germans. They parted ways, and that was the last time anyone ever saw Nothdurft and Mayer alive. Corti fought for survival for four days, huddled in the red bivy tent on a small ledge, 250 metres below the summit.

Corti's struggle to survive the Eiger, Longhi's painful agony and ultimate death, the brilliant operation (masterminded by Lionel Terray, Ludwig Gramminger and Erich Friedli) to rescue Corti, and the four years mystery surrounding the disappearance of Nothdurft and Meyer, all make for one of the most famous climbing stories ever. It's a story that has been retold, with varying degrees of accuracy, in many books. Unfortunately for Corti, the most famous and successful of these books - Heinrich Harrer's 'White Spider' - has always been the least accurate of all the accounts. Because of its bizarre mixture of prejudice and sensationalism, 'White Spider' deliberately marked Corti as one of most notorious scoundrels of mountaineering history, even long after the discovery of the fate of Nothdurft and Mayer an event which should have cleared his image.

The 'Corti Affair', as it came to be known, began literally minutes after Corti was hauled to safety to the top of Eiger. Delirious, and dangerously close to a final collapse - he had lost almost 20 kg in 9 days - he addressed his saviours in a disconnected, barely comprehensible manner (Corti almost always spoke in his native Lecco dialect). Still, his incoherent statements on the summit were later to be used against him.

Once on the Interlaken hospital, journalists had free access to Corti's room all hours of the day and night. The most assiduous was Guido Tonella, an Italian Swiss writer who had made headlines in the 30's with his coverage of Riccardo Cassin first ascent of the Walker spur. As he spoke Italian, Tonella had a privileged position among the correspondents who had flocked to Grindelwald in the wake of the tragedy. Everyone had questions for Corti, and Tonella, in a self-appointed role as translator, became the major source of information for most of the international press, bombarding Corti with insistent requests for every detail of the ascent, including the most important question of all: the fate of Nothdurft and Mayer,.

Corti could do little to react to this pressure. Still very ill, and not used to dealing with the press, he agreed to answer Tonella's questions, not knowing that the journalist was feeding the rest of the press with gruesome rumours. Meanwhile, two other people begun to feature in this tragedy: Riccardo Cassin, and Carlo 'Bigio' Mauri (later to climb Gasherbrum IV together with Walter Bonatti,). Both had been on the summit while Corti was being rescued, and Mauri had been a friend and climbing partner of Claudio to the point that Claudio saw him as a 'protégé' of a sort. Once in the Corti hospital room, Cassin and Mauri opened the conversation with a barrage of abuse. They accused Claudio of irresponsibility, of abandoning Longhi to his fate out of cowardice, and because of the rescue, to have brought shame to Italian climbing. Cassin's views were still those of the 30's, when being rescued was synonymous with disgrace; and moreover, his short temper was legendary. But Mauri's hostile attitude an unexpected blow to Corti.

In all probability, it was not just a matter of Italian climbing honour being at stake. Cassin and Mauri were in Grindelwald because they had aspirations on the Heckmair route, and Corti had very nearly 'stolen' the first Italian climb of the Eigerwand from both of them. In the rigidly hierarchic world of Italian climbing of the 50's, Corti had made an unforgivable faux pas and Cassin swore to teach him a lesson, and because of his prestige, he was able to do just that.

When Claudio finally returned to his home on Olginate, Nothdurft and Mayer were still missing, and most of the media were openly insinuating Corti knew more than he had admitted about their eventual fate. While his closest friends had no doubts about his innocence, everyone else seemed to suspect the worse. In Germany and Switzerland, few magazines flatly accused him of having murdered the two German climbers to steal their gear - his head wound was now attributed to an axe stroke. Again, the these accusations were boosted by Tonella, Harrer and Kurt Maix (busy editing the final version of 'White Spider'). Evidence for all this was non-existent, or second hand. For instance, Tonella wrote an article stating that aerial photos had now “conclusively demonstrated that Nothdurft and Mayer had been with Corti all the time, until just before the rescue”, and that, “Corti was lying”. Later Tonella admitted he had never seen the pictures before writing the story - he had been told about them by “a reliable source”.

Tonella and Harrer's account resulted in bringing Corti to the attention of the German police, who paid Corti a visit in Olginate, with Tonella again on translation duty. Naively, Corti accepted this weird 'interrogation', and again Tonella used Corti's confused answers as evidence against him. In a final coup de theatre, Riccardo Cassin used all his considerable status to settle the matter; in a dramatic meeting of the Italian Alpine Club, he asked for the expulsion of Corti from the club. The core of the 'Ragni', who knew Corti well, voted against this proposal and the request was rejected. Seeing this as a personal attack to his position, Cassin resigned as the president of the Ragni, opening a rift that would take years to heal.

When 'White Spider' was released, Corti became a pariah; people wouldn't talk to him, and even his work suffered from all this negative publicity. The book contained a grotesquely distorted portrait of Corti, ignoring his climbing résumé, and describing Longhi as little more than a climbing beginner who had no place on the Eiger. Some of the points raised by Harrer were surreal - for example, he wrote that Longhi didn't know how to tie a prusik knot. In fact Longhi had been a climbing instructor with the Ragni, and of course knew how to tie all the basic climbing knots.

For the general public, Corti was perceived as at best incompetent, and at worst a murderer. Harrer was so convinced of his suspicions, he even paid for a search at the base of Eiger, looking for any trace of the missing Germans. Meanwhile, Longhi's corpse was still stranded on a ledge, 50 metres above the Traverse of the Gods, fuelling a ghoulish form of sightseeing from the terraces of the hotels in Grindelwald. Corti begged the CAI to organise the recovery of his friend body, but no one answered his requests. In 1959 a Belgian magazine paid a group of Swiss guides to do the job, and Longhi was taken back to Italy. The autopsy revealed he had a broken leg. This seemed to vindicate an important part of Corti's tale, but his position was so compromised by then that an Italian magazine ran a lengthy piece where the author explained that Longhi couldn't have broken his leg in the 1957 fall - aerial pictures taken during Corti's rescue had showed Longhi moving, and climbers with broken legs can't move. I wonder how this guy would explain the same thing to Joe Simpson.

A few people continued to defend Corti; Life Magazine ran a long story that was quite sympathetic to his position. Most of 1957 rescuers maintained they believed in Corti's innocence - Hellepart even visited Corti in his home one year after the rescue. Then, in 1961, Nothdurft and Mayer bodies were finally found on the West Face - the normal Eiger route. They had summited, but had been killed by an avalanche during the descent. Some of Corti's gear was found on their bodies and suddenly it became clear he had always been telling the truth.

In spite of many requests, Harrer never changed his position, more or less renewing most of his accusations in all the subsequent releases of 'White Spider'. A far more even-handed attitude was taken by Jack Olsen's 'The Climb Up to Hell', released in 1962. Olsen painted a relatively sympathetic portrait of Corti, clearing him of the most sordid accusations, but also showing him as an obsessed simpleton, and again detailing little of his climbing accomplishments. Corti had become, once for all, the 'prisoner of Eiger'.

Tonella's motives for pursuing his crusade could probably be attributed to the pull of sensationalist journalism; it's more difficult to understand Harrer. He never met Corti personally, so it is difficult to attribute it to personal antipathy. As in the Cassin's case, Harrer's view may have been simply those of the 30's, the golden age of alpine climbing - if you had to be rescued, you had no place in the mountains. However, in Harrer's case, this righteous attitude would have been a little misplaced - in 1938, he and Kasparek HAD been 'rescued' by Heckmair and Vorg while on their way to a first ascent - but reading between the lines of 'White Spider', some subtle, darker undertones are difficult to ignore.

Most of Harrer's audience was in the German-speaking world, and Harrer seemed to take particularly care in painting Italians (in the mid 50's, still the 'traitors' of the War axis) as desperately incompetent, and in some way unworthy of such a difficult and serious line as the Nordwand. He tried this trick again with the two teams who completed the first Italian ascent in 1963, hinting at their 'amateurishness' (and completely ignoring that three of them - Mellano, Perego and Aste - were among Europe's best alpine climbers of the early 60's). He also tried it with Bonatti, hinting that if the great Walter had never climbed Eiger it was because Eiger was “not his cup of tea”. The Eiger was never Bonatti's interest, but he gave it a serious shot in 1963 when he made his solo attempt that failed due to a injury caused by rockfall.

While Tonella and Harrer's responsibilities on Corti's public lynching are impossible to underplay, it would be unjust to both of them to overlook the role played by the Italian climbing establishment in allowing the lynching to be done. While the Ragni regrouped around him, the CAI officialdom more or less abandoned him to his fate, and made a timid attempt at a review only after Nothdurft and Mayer's bodies had been found, and after Toni Hiebeler (one of the member of the team who did the first winter ascent of Eiger in 1961, and the editor of climbing magazine 'Alpinismus') had written a vitriolic article in defence of Corti. In many ways, Bonatti suffered the same fate, but Bonatti was Bonatti, and had a long experience in dealing with the public, Corti did not.

What saved Corti from insanity was common sense, a strong religious faith, and the help from his family and friends. For few years after 1957, Corti had alternated bouts of depression (particularly in relation to his failure to have Longhi's body recovered) to a profound desire to 'clean up' his image as climber. He even thought about climbing the Eiger again but then he got busy repeating routes, particularly in Bregaglia and his beloved Grigna. It was a frenetic, and often reckless activity. Corti was a strong climber but strategy was never been his strongest point. Mike James' story of this 1961 climb of Piz Badile is a good example of what was Corti at that time: brilliant but almost indifferent to danger - something he had in common with many famous names of that age. Corti's great assets were his strength, his loyalty and his dependability, in and out of the mountains. One episode may shed light on this: in 1956, together with Annibale Zucchi, he twice attempted to repeat the Bonatti Pillar on the Dru. The second time a sudden rockfall had hurled them 500m down the couloir leading to the pillar. Zucchi was severely injured, but Corti, despite being in a terrible shape himself, carried him all the way to Montenvers.

Corti recognised eventually that the only way to personally survive was to put the Eiger episode behind him. On her deathbed, his mother asked him to forgive everyone, particularly Harrer - “because there's more good than wicked people in this world”, were her last words. His wife, who understood his inner pain, was also a strong healing force in Corti's life and helped him to channel his angst into something constructive. In 1968 he returned to the Western Alps, climbing several difficult routes including the East and South Face of Grand Capucin. He climbed again with Cassin, and urged the rest of the Ragni to make peace with him. He made the second ascent of his own route on the North East Face of the Piz Badile and, most importantly, he got invited on the Casimiro Ferrari Expedition to Patagonia, playing a key role in the first ascent of the West Face - a climb that for many is the first real ascent of Cerro Torre. Corti could not reach the summit, but his strength, skill and dependability were of immense importance to the success of the team. In 1975, after having ascended Mount Kenya, he retired from active climbing.

But the Eiger continued to lurk behind him. The true story of the 1957 climb had been never fully told, and 'White Spider' continued to be re-printed. Several friends and admirers of Corti wrote to Harrer asking for a public retraction, but this never came. Even Dino Piazza, the great old man of the Ragni di Lecco, wrote to Harrer but he never replied, and the 1999 re-release of the book featured, again in full, all Harrer's accusations and insinuations. Legal action from the Italian Alpine Club against the Italian publisher of 'White Spider' could have solved the situation, but Corti seemed not to care. He refused to be interviewed or even to discuss the 1957 affair in public until 2002.

Then, between 2003 and 2008, a string of new books reopened the case. Daniel Anker and Rainer Rettner published 'Corti Drama' - a stunning photographic book on the 1957 rescue, re-assessing for the first time that tragic event as it had really happened. Giovanni Capra (an Italian sport journalist) published a long reappraisal of the 1957 affair in his history of the first Italian ascent of Eiger, making clear to the Italian public that Corti had suffered an enormous injustice, partially at the hands of fellow Italian climbers. In 2008 Giorgio Spreafico published 'The Prisoner of Eiger', a long and detailed look on Corti's life, and probably the most accurate look of the 1957 accident ever written. Harrer had died in 2006 without recanting a line of his 'White Spider'. His version of the 'Corti affair' can't be taken at face value any more, but the global popularity of his book will probably insure that, for the general public, Claudio Corti's name will be forever linked to the cowardly, incompetent caricature of the book.

Corti's health in the last few years had taken a turn for the worse, and in 2008 he suffered the amputation of a leg because of his diabetes. It's not difficult to imagine that death freed him from an increasingly difficult burden but, even if maybe too late, he lived long enough to see some justice done.

An extract from Claudio Corti climbing resume (first and second ascents only):

Comments