Tom Briggs works for Jagged Globe and is also one of the news editors of UKClimbing.

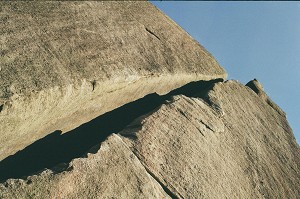

We were at the base of 'the right hand tram line', part of a vague feature that made up our route on Southern Greenland's unclimbed, 600m 'Baroness' wall. Unclimbed until last night that is, when Airlie and Lucy had topped out on their line. We'd spent 4 days of effort towards the central part of wall. The climbing had been plain hard, the main problem being the unrelenting steepness. Some of it was hard in a British style ‚ runouts above crap gear with the odd bit of dodgy rock thrown in. Some of it was hard in a very non-British way ‚ 60m vertical granite offwidths. This is all fine for a few pitches, but it's draining when it's pitch after pitch, when the climbing is never straightforward and when the route finding is always complicated...because you can never find an easy option!

We'd jugged 7 pitches and climbed 3. I sat on the ledge, feet dangling; just space below, working out how many and how complicated the abseils would be to get off this thing. I thought about getting off the route most of the time I was on it. Maybe it was because our heathery base camp was so comfortable? Maybe I preferred talking about 'strategies' more than implementing them? Maybe it was because I was entering this new realm of experience ‚ pushing into the unknown, taking risks on a big imposing cliff, miles away from the nearest civilisation. And it was strange because Matt was an Alpinist ‚ he knew all about hard work and risk, but I knew he was also having doubts. The challenge of this route was different from being in the mountains; it was unique to this type of climb on this size of cliff in this type of place. Matt's doubts weren't doubts about risks from objective dangers, the cold or the weather. Come off it - the sun was out, we had food and water! It was much simpler than that. I took a look at the groove above.

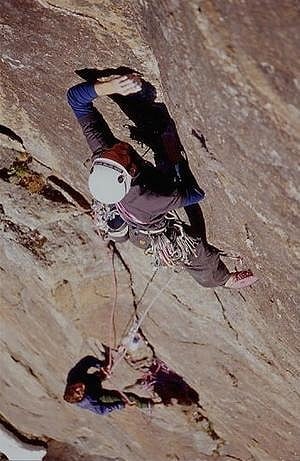

The groove was shallow, with a gritstone-style arete on one side and a smooth granite wall on the other. A Friend went in just above the belay ledge, but above that it was obvious that there was no gear for another 20 feet or so. Just standing above the belay ledge felt precarious, the only holds in the groove were a few crystal crimps, nubbins and smears. I tried piecing a sequence rightwards that I knew wouldn't work, drawing confidence from making a couple of difficult moves just for the hell of it. But the challenge was obvious ‚ there was a small pedestal on the left edge of the corner, from there, a crack above would be in reach. There was no other option but to climb this groove, there was nothing to aid on, no clever pendulum to make to an adjacent feature, this was it - make or break, do or die, delicate bridging or broken leg.

Matt was still silent and I could tell that he was thinking about how it was getting late, how there wasn't any gear, how I couldn't afford to fall off, how we'd put in so much effort and we were going to fail. It felt like an hour at the base of that groove, tinkering about, trying out different combinations of holds, none of which were particularly positive. But it was all part of the process and there were enough holds. I reversed back to the belay ledge, sat down and took my shoes off. By now I was in the right state of mind to commit myself without approaching it in a rational or responsible way. I had half a sequence secretly worked out and was about to find out how it fitted together with the other half.

I put my shoes back on, chalked up and launched into my boulder problem. 15 feet above the ledge, I'm rocking up high into an awkward bridging position on smears. Adjusting my weight whilst trying to maintain balance, I reach what I hoped was a jug and gear placement ‚ it turns out to be a dreadful sloper and a wobbly Rock 3. I pause, starting to shake a bit now, before making the committing mantelshelf onto the pedestal, reaching the crack and safety.

This was the challenge of this route, but it was also the reason why I kept thinking about giving up on it. We were at our limit on steep ground. There were so few options, that we were just waiting for that blank section which would stop us and put an end to our dream route, for the holds to literally run out. Failure seemed so likely, that to give up before you'd wasted too much energy seemed more attractive most of the time. You can look through binoculars all day from a mile away, but all it had to take was 20 feet. Our 20 feet just had enough.

Comments