Interested in how climbing gear is currently made? UKC have an exciting video coming up - featuring the making of a carabiner in the DMM Llanberis factory. Watch this space!

Virgil Scott takes a look at carbon fibre carabiners. His research has led him to believe that the future of climbing gear lies in this area. Is he right?

Carbon Fibre Carabiners - Is It Possible? by Virgill Scott

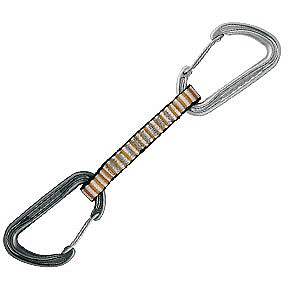

The lightest full size carabiners available weigh around 33 grams. A testament to this engineering feat, when shown a carabiner, an engineering professor at Imperial College assumed it was hollow because it felt so light in his hand! It has taken many years of incremental changes to reach this figure – but imagine if it could be reduced to 20 grams in one step. A 40% weight saving – which could also be applied to smaller carabiners such as the DMM Phantom (UKC Review) or CAMP Nano.

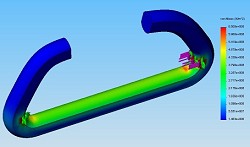

Composite materials are used in spaceships, jets, tennis rackets, boats, bicycles – and countless other applications. Why? Almost always for weight saving. Promisingly, much like the climbing industry, most of these applications previously used aluminium alloy because of its excellent strength to weight. A typical carbon fibre laminate has double the strength-to-weight ratio of carabiner aluminium.

However, composites aren't without problems. Climbing gear must be able to cope with a very unusual combination of demands – sudden and very large forces, heavy abrasion from pulling down wet and sandy ropes, corrosion from salt-water, big temperature ranges (from -40°C on Everest to +50°C or more due to friction heating). As they are now, carabiners are amazingly robust and any modifications made must be considered very carefully. For example, would it be acceptable if a carabiner was 40% lighter but also wore out twice as fast from abrasion?

Having said that, it may not be necessary to make this compromise. Composite gears have been used in NASCAR racing, where wear characteristics are absolutely vital, and they are purportedly lighter and longer lasting than their metal counterparts. This is due to additives used in the plastic resins – much like the alloying process used for metals. It may also be possible to use hard layers or coatings to protect from wear.

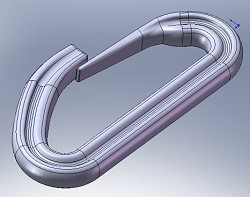

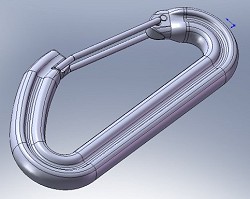

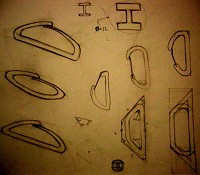

Injection moulding is fast and automated – it would take minutes rather than hours to create each carabiner. Also, it may be possible to design a carabiner that can be made in a single step; this would require the gate to be integrated into the carabiner body so that the entire carabiner is made as a single component. The gate would be made out of a thin strip of material so that it could bend open. This would need to make use of a captive-eye design (where the carabiner cannot be cross-loaded) and would have to take advantage of the additional strength offered by composite materials to overcome the fact that it would essentially be continuously in the open-gate configuration. Even using a more conventional wire-gate design – injection moulding the carabiner body would cut out several steps in production.

It will take some bold steps to initiate the adoption of composites but the potential pay off is very great. Climbing gear is a dynamic and innovation led industry, even with the weight savings aside, being the first to produce a composite carabiner is likely to add value to a brand. This, plus the additional value of formidable weight savings, could make a market leading product.

Fact or fiction?

UKC got in touch with DMM of Llanberis to find out if carbon carabiners are pure fantasy, or whether they might actually be hitting our shelves, and our racks, any time soon.

Simon Marsh from DMM had this to say:

“New materials are always interesting and certainly from a DMM perspective I would think history shows that we constantly push the boundaries - Predator, Terminator, Revolver and Shield to name only a few.”

“We have certainly looked at carbon fibre in the past and indeed brought a couple of carbon fibre products (Deadman & Snow Stake) to the production stage before our partner, who was actually producing the units, went bust.”

“We constantly look at new materials and do this at many and various levels of differentiation. We have been talking to a couple of companies about composite materials that could replace metal products for the last couple of years and it is a really exciting area.”

Interested in how climbing gear is currently made? UKC have an exciting video coming up - featuring the making of a carabiner in the DMM Llanberis factory. Watch this space!

Links to featured manufacturers:

More information on carbon fibre carabiners is available on Virgil's Website

If you want to know what the future of climbing gear really is, why not read this futuristic UKC essay 'Perfect Partner' by Robert Walton, featuring some innovative and interesting technology...

- Expedition report: Raru Valley in the Himalayas 6 Dec, 2011

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Taghia, Morocco 13 Aug, 2009

- Trip Report - Taghia Gorge, Morocco 5 Jul, 2009

Comments