A Few Thoughts About Risk

Risk is a highly abstract and elusive concept. It is about things that might or might not happen. If they do happen then it is no longer a risk but a consequence at which point the clock can't be turned back. Ideally you would give risk more thought before an accident but human nature being what it is, it takes at least a close shave or two to consider it seriously.

Maths, statistics and board games don't give us a good start in life as youngsters to think about risk. The outcomes and probabilities of rolling a dice are hopeless decision making tools and analogies for dealing with the complexities and unknowns of the real world whether they be successful decisions on buying a house, getting married or choosing a career. A vivid imagination, alertness, an open mind, self-knowledge, independence of thought and logic are far better qualities for managing risk in our lives and climbing.

I thought it would be useful to explore a few characteristics of our lifelong elusive shadowy companion; Mr Risk. He is your personal intermediary progressing into a future world of infinite possibilities where only one unpredictable sequence will play out. In other words he is someone that is worth your while making an effort to get to know.

Stay lucky

When Donald Rumsfeld was famously laughed at by reporters for talking about 'known, knowns' * etc it was the reporters who were being dumb. Astonishingly (for a politician) far from being economical with the truth – he had dolloped it out in spades. Donald teaches us why there is a lot that is uncertain in predicting outcomes and the limitations of risk management. The unexpected unlikely nasty event is more frequent than is commonly assumed - anyone who reads the excellent current best seller the 'Black Swan' will know what I am on about here. The unexpected is to be expected, the problem is you don't know what form it will take. The very 'safest' of climbing activities can have unlikely nasty outcomes as occurred to the inexperienced Mr Gary Poppleton who was ambitiously jumping for a hold when bouldering indoors but was still very unlucky ending up quadriplegic when he landed on his head on a 'safety' mat. I've landed on my head whilst snowboarding and 'deserved' a broken neck more than he did. Poppleton tried to sue the climbing wall and the judgement is here: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2008/646.html

Anyway, my first point is however safe you make your climbing, by choosing to climb you put yourself at risk of being harmed. If you think otherwise you are fooling yourself. So either be lucky or choose not to climb – these are the ONLY two ways that absolutely guarantee you will not to harm yourself climbing.

What are the stakes?

Obviously death, but alternatively injury – and I am not talking tweaked tendons. If we compare Cliff Phillips who, whilst soloing, fell a long way off Dinas Mot but managed to drag himself back to his car with the aforementioned Mr Poppleton it is clear that the severity of the injuries are not directly proportional to the length of the fall and the softness of the landing. This spectrum of possible outcomes from a fall makes a nonsense of simplistic risk calculations. But, consider that bouldering (considered safe) features groundfalls as a regular occurrence whilst leading routes (considered risky) features groundfalls as an irregular occurrence. At some unknowable point the probability of paraplegia will be the same for a lead climber as a boulderer when the low risk, but regularly occurring, groundfalls of a boulderer equate to the high risk of injury, but irregularly occurring, groundfalls of a lead climber. This was pointed out by John Cox on the forums and whilst hypothetical, usefully challenges accepted notions of 'safe' bouldering and 'unsafe' leading or soloing. Another 'stake' to think about is how important is it for you that you stay alive. As a middle-aged man with a growing family the stakes are now far higher for me now than when I was a student with no responsibilities who having read too many existentialist novels took higher risks on my current existence than I now find acceptable – the git.

I don't think I need to labour this one as I think it is accepted that a beginner will be oblivious to a lot of risks that are obvious to someone more experienced. As a sentient being the beginner should be able to appreciate and anticipate that falling on your head might break your neck, as this type of risk is not exclusive to climbing. Less obvious are the mechanical tricks like directional forces on runners, making good placements, backing things up, stability of rock types, not threading and lowering off through a piece of tat etc etc etc. The technical and equipment aspects of lead climbing form a usefully high barrier to entry for the absolute beginner. By contrast a low barrier to entry can lead a tourist to end up accidentally lost in the mist or solo-scrambling in the Lake District. It usually takes a bit of skill, equipment and (misplaced) confidence or ambition for new leaders to enable themselves to get into deep shit – a little bit of knowledge being a dangerous thing.

In truth I am not sure what the best answer to education is. Personally I learnt as I went along, climbing with other students at the University Club. It was riskier from a best practice point of view but self-reliance was a given, and you were fully alert to danger and engaged, even if misdirected at times. Being trained by an Instructor might dull the immediacy of self responsibility and self reliance and also reduce the depth of understanding and habit forming that self-learning and discovery provides. The taught way also isn't necessarily the only and best way for all circumstances. If you learn from first principles what constitutes an adequate belay, for example, this gives you flexibility of thinking and options for a wider range of situations.

Youth puts you at risk

Not all beginners to climbing are young but the young are observably less risk averse, to say the least. I think we can safely say young men particularly so, who are also more prone to excitability and peer pressure. I have watched David Attenborough documentaries on primates and their social behaviours and drawn my own conclusions.

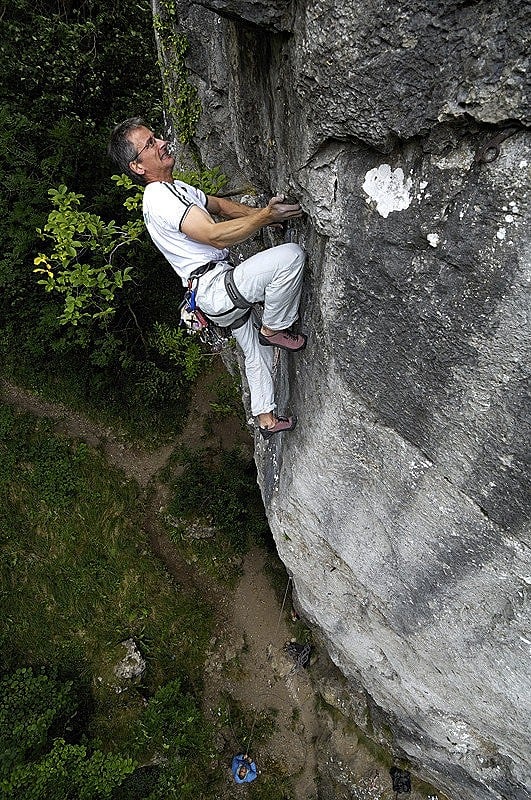

Experience puts you at risk

There are two things at work here. One is that an experienced climber is a prolific climber. The more time you spend climbing means the sum total of the time you spend in harm's way allowing more chance for an accident to occur. I am thinking here of accidents that prolific climbers such as Martin Crocker had, decking out in Cornwall when he shouted 'take' and his partner thought he said 'safe' and Gary Gibson slipping off the top off Moat Buttress to land in the mud. The second thing is that experience can lead you to lower your guard and so your 'risk glands' are asleep on the job when climbing is so familiar; especially doing something 'safer' like sport climbing. I tie my figure of 8 knot without looking at it. In fact I found it very difficult to describe and demonstrate tying it to a newcomer (“stop doing that funny thing with your wrist !” she said ). All of us have made mistakes with mundane semi-automatic activities that lead us to put the teabag in the sugar bowl. I am not alone having started up a climb with an incomplete knot from being distracted halfway through tying it. Similarly most of us check our knots more closely when attempting a harder route because we anticipate and imagine falling but don't check the knot as closely when setting out on an easier route even though the impact of hitting the ground is the same. Similarly I like using Gri-Gris because they are convenient but they also make you complacent and it is easy to put the rope the wrong way round in them or not clip both eyes through the screwgate when those actions become so automatic.

Risk stripped bare - even

Headpointing is an interesting branch of the sport from a risk perspective as it removes as much of the uncertainty out of lead climbing as it is possible to do. By practising the moves to perfection and sussing out the best gear placements prior to leading, headpointing removes those uncertainties present in onsighting. Removing the extraneous uncertainties, I imagine, forces the individual to confront the actual danger square-on prior to deciding to lead, for what to the outsider appears a suicidal undertaking as the climber is close to their climbing limit. But the headpointer will be utterly focused and prepared for the undertaking. In most cases the risk might be equivalent to a prima ballerina landing on her arse at Covent Garden**, in the sense that whilst difficult, the danger is more apparent than real. To my knowledge no one has died from headpointing yet, despite some notable close shaves and groundfalls – although admittedly it is still a minority pursuit played out primarily on short gritstone routes. An interesting juxtaposition was when Seb Grieve was practising the route 'Slab and Crack' at Curbar on top rope which he was planning to headpoint. His girlfriend, who was belaying him, dropped him the full height of the crag. The risk of groundfall on the route was realised in an entirely different way from what he expected.

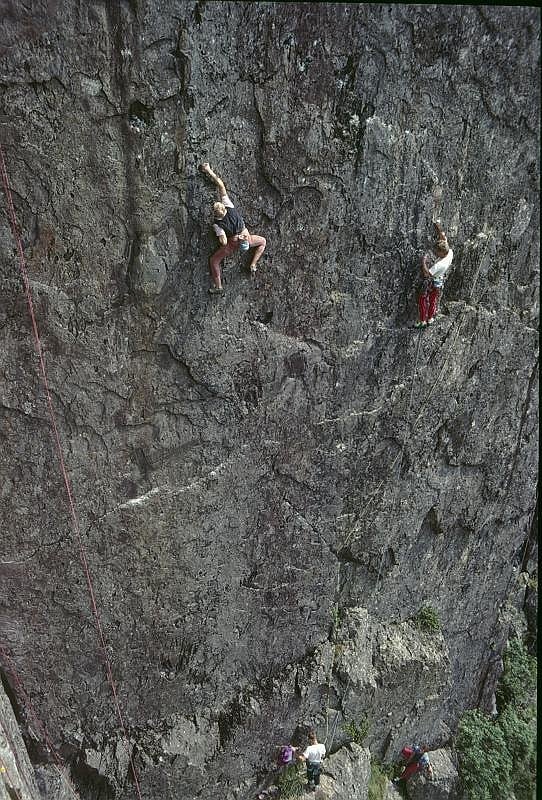

Like in headpointing the soloist is usually utterly engaged in the task in hand and this makes it less risky. This alertness and attention makes for safer climbing especially as you are uninterrupted by the tiring and tiresome stop-start of gear placing. In contrast to Headpointing, Soloists would tend to solo well within their limit and probably be the type to climb confidently and be less prone to losing it. Compared with a hesitant lead climber pushing themselves on spaced gear, the risk might be less. The same applies for someone leading an easier route but being lackadaisical. One of the first E5 climbers I knew claimed he had taken his biggest fall on an HVS – over 100ft if I recall rightly – because he wasn't concentrating and hadn't placed enough gear.

Soloing is more dangerous than leading

The sum total of our climbing is important. If you solo very occasionally you will be unlucky to come a cropper. If soloing becomes a major regular activity as it did for Paul Williams, Jimmy Jewel and Derek Hershey you have to accept that the sum total of your soloing activities mean that the unexpected event ie it starting to rain whilst on a slab pitch, an oft-used hold snapping, a bird flying out a hole goes from being unexpected to expected because you do so much soloing. As a soloist you end up climbing much more footage, spending far more time on the rock which is one of its attractions but also compounds the risk as you are spending more time in harms' way. It is not inevitable that you will die as a career soloist, as Ron Fawcett is living proof, but it is more likely.

Alpinism and Russian roulette

It was very apparent to me on the 10 days I went Alpine climbing in 1984 that not only did it involve unacceptably early starts but also, for me, an unacceptably high level of danger for something that was not that enjoyable. It seemed to me that your ability to influence or control the risks are so marginal that you make yourself a virtual hostage to fortune. To climb in the mountains you have to accept that chance plays a greater role and you can't control the risks as much because you are putting yourself in what is termed 'objective danger' from rockfall (naturally occurring and dislodged by climbers above), bad weather and so forth. However, the desirability for speed entails cutting corners and the effects of tiredness on judgement compounds risk further – both being additional 'non-objective' but still inherent dangers. In my view the most important decision comes from choosing whether to go Alpineering or not, as opposed to how you carry it out. Once in the game and assuming you survive the short term you might extend the odds a bit by refined judgement on decisions relating to general rockfall and bad weather avoidance. But, the more time you spend up there on the hill, exposed to potential harm, the higher the likelihood of killing yourself. Additionally in the Alps there are opportunities for people to escalate disaster by taking out several parties in a fall or by inducing an avalanche. By comparison outcrop climbing incidents are generally non-escalating.

Conclusion

This is by no means a full consideration of risk, which is beyond my faculties anyway, but I hope it will prompt a few thoughts about it. There is much we can't perceive, quantify, control and manage with respect to Risk. That's the context. Realise it, then forget about it. There is after all no point worrying about what you can't control. In fact enjoy it. Risk makes you feel more alive and switched on to the world around you. But there is stuff we can influence in our choices about the types of climbing we do and the way we practise it – always learning of course. If those things are broadly aligned to the level of risk you feel is right for you or what you get out of the sport then I think you have chosen appropriately, irrespective of whether it kills you or not.

*Full quote: “There are known knowns. There are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we don't know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we do not know we don't know.” Toby Foord-Kelcey, a frequent UKC contributor, suggests that an example of an 'unknown unknown' in climbing was Tommy Caldwell and friends being shot at then kidnapped by terrorists whilst climbing a big wall in Kyrgyzstan.

I propose a further example of Pete Biven whose attempt at a route in Lundy led him to be ditched in the sea in a helicopter and dealing with the unforeseeable hazard of trying to swim whilst still strapped to a stretcher. I would love to collect further examples – preferably of the non-fatal variety. Here are potential climbing KK's, KU's and UU's:

1.

Known knowns: (Certainties/Information)

- I can get pumped climbing

- The rope has a fall rating of six and I have fallen on it twice

- There is a serac above

2. Known

unknowns: (Uncertainties/Judgement)

- Whether I will be able to climb fast enough to avoid getting pumped

- Whether the stretch in the rope will mean I hit the ledge if I fall off above the crux

- Whether the serac will collapse whilst I walk quickly underneath

3. Unknown

unknowns: (The Unknowable/Luck)

- The red wine I drank last night had a pump-inducing toxin

- A rat chewed the middle of the rope last night

- Arguing about walking under the serac, my partner stabs me with an ice axe

** Re-reading that has just reminded me – one of my very first falls was onto my backside on Covent Garden at Millstone. Coincidence or what?!

- Training - Why Bother? May/2008

His all time climbing highlights are: "Troll Wall 8 months after first lead in '84, soloing Rainbow Bridge in '86 including the aid pitch, redpointing Zoolook by the skin of my teeth in appalling weather after a year of effort in '94 and first trip to Yosemite in '97 with 6 weeks of great weather and good company."

Comments