On International Women's Day, Anna Fleming delves into the life of Alison Hargreaves, illuminating the changing role of women in sport and society as well as the challenges of balancing work, life, family and climbing.

17 February 1962 – 13 August 1995

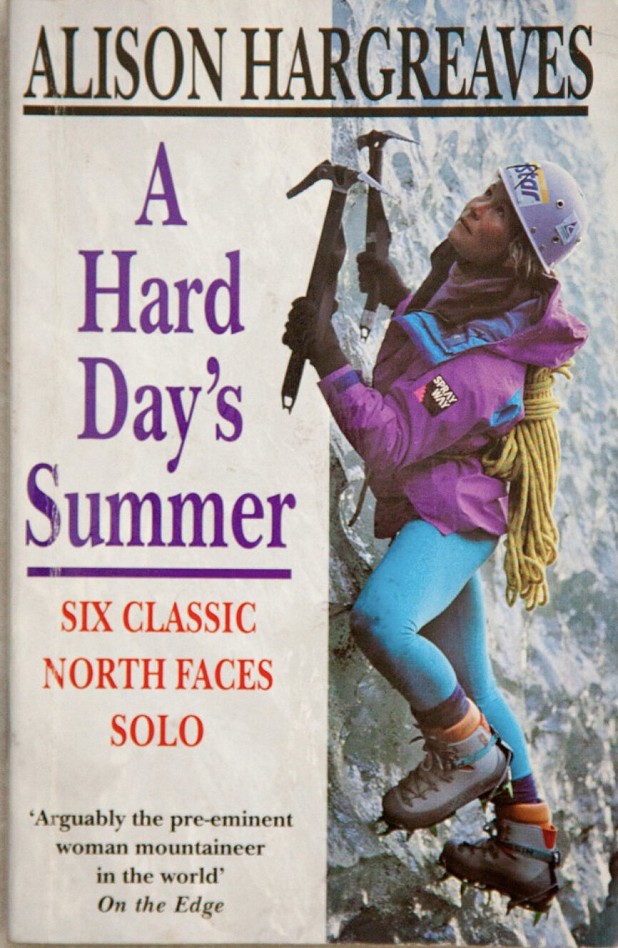

'The mountains are there to be climbed and enjoyed not conquered. I feel when solo climbing more attuned to the elements than at any other time... If everything is right, you may be allowed to climb your mountain.' - A Hard Day's Summer

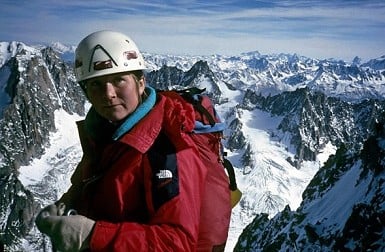

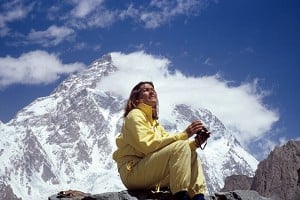

Alison Hargreaves was one of Britain's all-time greatest mountaineers. When few female climbers were making headlines, she undertook bold and ambitious alpine expeditions in the Himalaya. In 1995, she scaled Everest completely solo and unsupported. Two months later, she died in a storm on K2 and the press turned on her: how could a mother of two young children take such risks? Her death highlighted the double standards applied to male and female climbers.

Born in Derbyshire in 1962, Alison came from a middle-class family who encouraged her mountain interests. At age 8, she scrambled across Crib Goch in wellies and her father took her scrambling, hillwalking and climbing. Alison's teenage bedroom was filled with posters of her beloved sport. Beneath images of mountains and climbers she pored over books like The White Spider.

Alison's enthusiasm for mountains grew during a family holiday to the Austrian Alps in 1976 and a school expedition to Norway in 1977. Together with her friend Bev, the 15-year-old girls travelled to the Arctic Circle where they stayed in Rago National Park to measure glacial recession.

Back in the Peak District, Bev and Alison often went rock climbing. Two girls on a rope was noteworthy as the climbing scene was male, competitive and hierarchical, but Alison was not self-conscious as a woman climber. Unlike Polish mountaineer Wanda Rutkiewicz or British rock climber Jill Lawrence, Alison was not pushing a feminist agenda. Determined, strong-willed, mischievous and lively, Alison was a free spirit following her passion.

At 18 she left home on a fast-track to adulthood. Her parents expected her to go to university, but instead she moved in with an older man. They were shocked. Sixteen years her senior, Alison met Jim Ballard when she was 16 and working in his outdoor shop.

Jim offered material security, an escape from parental pressure and a gateway into adulthood. He was part of the climbing scene she so admired and could help her make headway in the world she longed for. He became her coach, romantic partner and business partner. The anarchy only ran so far: she was expected to play a traditional domestic role at home. She worked hard, but soon found that her best was not good enough.

Ambitious and driven, Alison wanted to be a great climber. The pressure did not only come from within. Jim was equally hungry for her success, as her biographers Ed Douglas and David Rose explain in Regions of the Heart: 'Jim was as vicariously ambitious for her as she was herself. As far as he was concerned, Alison was, or at least soon would be, the best female rock climber in the world.'

This was a huge weight of expectation to place on young shoulders, particularly since Alison didn't have the natural ability to fulfil that lofty goal. She was a good climber, but whereas her contemporaries Catherine Destivelle and Lynn Hill were climbing E6/5.12, Alison had climbed only a handful of E3s.

To maintain the world-leading position she felt she ought to have, Alison switched from rock climbing to mountaineering. It was a canny move. Her physiology adapted well to altitude and the variety of skills required. She started to come into her own.

In 1986 aged just 24, she received the invitation of a lifetime to climb in the Himalayas with world-famous American alpinist, Jeff Lowe. Together with Tom Frost and Mark Twight, they climbed new routes on Kangtega (6,782m), a difficult mountain first climbed in 1963. Anxious to prove herself on this all-male American expedition, Alison worked hard and on 1st May, alongside Mark Twight, Alison led a steep ice face to reach the summit of the main peak.

Afterwards, Twight wrote an influential article about the expedition. His essay gives a flavour of the culture Alison encountered on high altitude expeditions. Twight's writing bursts with cynical punk attitude, celebrating the masculine energy of alpinism. He did not mention Alison once.

Following Kangtega, Lowe and Twight left Alison to attempt a route on Nuptse (7861m). Alison was bitterly disappointed to have been left behind. She met Sandy Allan, who needed a partner on the south face of Lhotse Shar (8383m) after his previous partner had been injured by serac fall. Alison and Allan reached 6500m before they were forced to retreat due to avalanches.

Despite the challenges and frustrations on Kangtega and Lhotse Shar, Alison felt she was making headway in her grand mountain ambitions. But off the mountain, things were difficult.

She trained hard and worked at Faces, the climbing equipment factory owned by Jim, which supplied equipment to his Bivouac shops. But she was isolated and her diary (now kept by her mother) reveals chronic low self-esteem, loneliness, periods of directionless-ness and depression. Alison's diary, read by her biographers and quoted in the press, gestures towards the cause of these problems.

In 1983 she wrote: 'Enormous row and fite (sic). Frightened when kicked... Upset, cos JB said I didn't look after him.'

In 1987 she wrote: 'JB beat me up again, thumped and kicked me in snow.'

And in 1989, she wrote: 'I've nowhere else to go.'

The violence, according to her biographers, was only the tip of the problem. In a 1999 interview (Courage under Fire) for The Herald, Ed Douglas explains, it was 'the tip of the nature of his controlling behaviour. She had become more and more limited and narrowly focused within the relationship. She didn't have many friends and she wasn't part of the climbing community in a major way. She felt trapped, that her life was passing her by and it had all gone wrong. In many ways her life was fantastically oppressive.'

Alison Hargreaves is not the first mountaineer in this series with a background of domestic abuse. Early mountaineer Ellen Weeton also went on solo mountain expeditions to recover from a violent marriage. While Wanda Rutkiewicz never had a violent relationship, her seven-year old brother was killed by a bomb and her father was murdered. How many mountaineers have sought out the extreme highs and hardships of the mountains to cope with trauma?

In 1988, chasing one more high before she would be grounded for a while, Alison climbed the north face of the Eiger. She was five months pregnant. She sought medical advice and the doctor thought the risks were slight, but warned that a big expedition to Alaska (her original plan) might appear 'unseemly' — so he recommended the Alps.

Alpine climbing in second trimester pregnancy was uncharted territory. Alison managed the climb, but it proved difficult. She slept badly on the bivouacs as the baby kicked inside her. With legs swollen like balloons, she walked off, exhausted. Her climbing partner said that she didn't look pregnant before, but she did after.

By 28, Alison had had two children and was juggling many responsibilities, including childcare, training, running the home, working for the business and pursuing her goal of becoming a professional mountaineer. Despite or perhaps because of these responsibilities, in 1993, she became the first person of either gender to solo all six great north faces of the Alps in a single season.

She describes the climbs in A Hard Day's Summer, a book co-authored with Jim. The book paints a rosy picture of summer in the Alps, driving between valleys and campsites with Jim caring for the children while Alison left them behind to climb her routes alone in the heights. One critical missing detail is that the family were in dire circumstances. The business had failed and their home had been repossessed, making them homeless. Traditional gender roles switched: Alison became the breadwinner, climbing from a desperately insecure situation in the hope that her work would rescue the family.

She kept at it. On 13 May 1995 she became the first British woman to climb Everest alone, without the use of supplemental oxygen, unaided by Sherpas or other climbers. This feat drew massive attention, pitching Alison into the limelight on the double-edged sword of publicity. Whereas Wanda Rutkiewicz was worshipped in Poland (she even met the Pope) and Catherine Destivelle had successfully courted the French media, the UK press were ambivalent. A strong female mountaineer was not just an athlete; she was also a risk-taker and this was edgy for a British woman — especially one who was also a mother.

Alison's aim for the summer of 1995 was grander than Everest. She hoped to climb all three of the world's highest mountains unaided. But with the swell of attention after Everest, the pressure was reduced. She no longer needed to climb K2 and Kangchenjunga to make her name. But as usual, she was operating under a weight of multiple pressures. She had bought a house and after years of indecision was making tentative plans to strike out alone and become a single parent.

At K2, the climber's mountain, she missed an early weather window and waited for weeks at basecamp in a fretful state, torn between the two loves in her life:

'It eats away at me — wanting the children and wanting K2. I feel like I'm being pulled in two.' - Alison's diary entry, quoted in The Herald

She stayed on and eventually summited K2 in good conditions on 13th August. But as the climbers descended, a horrific storm blew in. With winds of more than 100mph, seven people died, Alison included. She was 33 years old.

Her death opened the floodgates for media abuse of climbing mothers. Among the commentators, Nigella Lawson and Polly Toynbee were particularly savage. Toynbee wrote:

"What is interesting about Alison Hargreaves is that she behaved like a man. She put danger first and her family a poor second. Equality means, I am afraid, men behaving as well as women, while women sometimes behave as badly as men."

Such discourse highlighted the disparity between genders and the familial expectations placed upon women. For, when a father died in the mountains, he remained a hero, his children presumably unaffected.

Combining parenting and climbing remains controversial and women still bear the brunt of the criticism. Among Alison's contemporaries, Lynn Hill and Catherine Destivelle waited until later to have children. (Hill was 42 and Destivelle was 37.) In a post-birth interview, Destivelle refused to criticise Alison:

"I could not do what Alison did, now I have Victor. But when a man dies on a mountain, people don't think of children. When a woman goes climbing, they do. It was Alison's choice, and why shouldn't she?"

Having seen what happened to Alison, Destivelle anticipated the media's response to climbing mothers. Her interview ran in The Independent under the patronising title, 'Mother of all Climbdowns', reporting on how Destivelle had chosen family over mountains.

Things have moved on a little. Last year, Helen Mort won the Boardman-Tasker literature prize for her book A Line Above the Sky, a love letter to Alison Hargreaves, exploring mountains and motherhood.

Top climbers Shauna Coxsey and Caroline Ciavaldini have opened up about their experiences of climbing during pregnancy and motherhood. Through films, social media and interviews they are creating a narrative that increases awareness, knowledge and support for women and their children. But nearly thirty years after Alison died, mothers still face criticism and abuse. In 2022, Shauna Coxsey spoke out about the online bullying she received while climbing through pregnancy.

Alison Hargreaves' life was short and eventful. Under intense social, emotional, financial and athletic pressure, she saw soaring heights and brutal lows. Juggling too many challenges, she gave everything to make it as Britain's first professional woman climber. In 1995, Alison stood on top of the world, while many were oblivious to the true scale of what she had surmounted.

***

In 2015, Alison's son, Tom Ballard, became the first mountaineer to climb the six major alpine north faces solo in a single winter season. Four years later, he died on Nanga Parbat aged 30. Read more about Alison and Tom in the UKC feature below.

- INTERVIEW: Catherine Destivelle - Rock Queen 8 Mar

- ARTICLE: Top 10 Borrowdale Routes at VS and Under 22 Jan

- ARTICLE: Herstory 7: The Rise of Women Mountain Professionals 27 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Herstory 6: Lhakpa Sherpa's Long Dream of Everest 31 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: The Climbing Cholitas: Skirts to the Top for Women's Empowerment 2 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: Wanda Rutkiewicz and the battle for women's climbing 13 Feb, 2023

- HERSTORY: Lady Climbers of the Long Nineteenth Century (1850-1914) 20 Dec, 2022

- HERSTORY: ORIGINS: The surprising origins of women's mountaineering - 1770-1830 9 Nov, 2022

- ARTICLE: The Cobbler: A Return to Mountain Cragging 7 Sep, 2021

- ARTICLE: A Climber in Lockdown 14 May, 2020

Comments

What a great article, thank you.

Great article, thank you. Didn't know that she'd climbed with Mark Twight etc. but been obscured, that's a shame.

I'm curious about her being the first woman to climb Everest unsupported and without oxygen. My understanding is that Lydia Bradey summited Everest in 1988 without supplemental oxygen, but I am guessing that this is considered a supported ascent for some reason?

Well that was great…thank you.

I think the arricle says first 'British' woman rather than first woman.

As for the article. Really enjoyed it, thanks to the author.