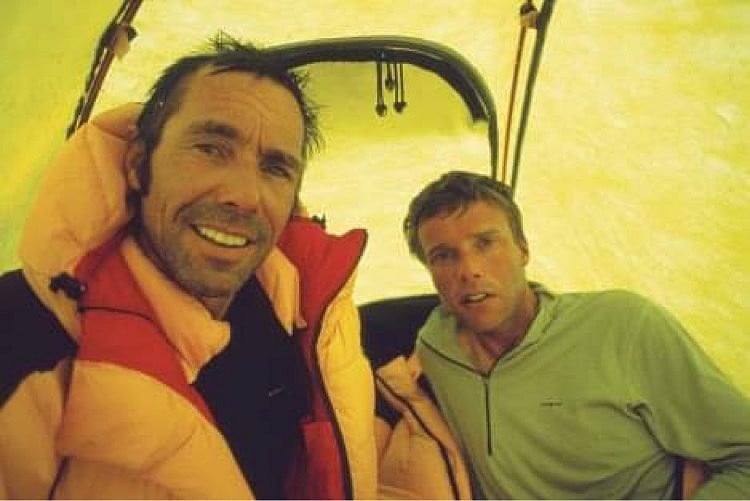

Charlie Creese remembers the character that was Athol Whimp, New Zealand's most accomplished mountaineer and the country's first recipient of the Piolet d'Or award, who died in 2012 in an accident in the Darran Mountains.

Maybe you've heard of Athol Whimp, maybe not. Most of his climbing was done in the southern and eastern hemispheres, and most of it was recorded – if at all – in a restrained, low key way, as befitting his "quiet operator" status. Athol resided in Melbourne for about 20 years, ran a business, had his ups and downs, and became something of a legend to those who didn't know him – or didn't know him well. I'm a little uneasy about the whole "legend" thing though. The term seems best reserved for constructs like "Agamemnon" or "Moses"; one person perhaps, maybe an agglomeration of people – they may not even have existed at all - but whose purported deeds have somehow made it down to the present.

Athol wasn't like that – he really did exist and his deeds are established facts. But there's no doubting he was larger than life - and that's saying something in a sport that has never lacked for that quality – his general stand-offishness from the scene only accentuating the mystique he'd already acquired from having been an officer in the SAS and an adviser with a desert reconnaissance unit in Oman. An overachiever. Fate had certainly helped him along in this regard – he was naturally athletic - a distance runner who – no matter what – always kept an evening free to jog around the Royal Botanical Gardens in Melbourne. Smart too; an autodidact really, a guy who could turn his mind to all manner of problems – from navigating in the desert to fighting parking fines in court – and invariably find a solution. The brain, as they say, is the most important muscle in climbing.

But even the above wouldn't have been enough to propel him to the heights he'd come to occupy in Australasian climbing in the '90s and early 2000s. No. The source of the mystery was this – that he was one of the most competitive people I've ever met. Mike Law's phrase – applied, naturally, to another Antipodean – springs to mind: "He's so competitive," said Mike of his rival, "he makes me look like Mahatma Ghandi." That competitive.

Don't believe me? OK - so we're driving down Lygon Street – Melbourne's Italian precinct. We used to spend a lot of time there drinking coffee – Athol's stimulant of choice – and – latterly - mine too – our avoidance of alcohol putting us – somewhat ironically - in the same company as Donald Trump. We're discussing a mutual friend who'd gone off on a climbing trip to a remote location after having only recently suffered a bereavement. It seemed a strange thing to do – unseemly almost - and we were speculating as to why.

"Maybe," I conjectured, "they're trying to hide their lack of grief." Athol turned and looked at me and I'm thinking "No way - I've offended him!"

But he wasn't offended.

"Fuck you're cynical Charles," he said, voice betraying just the faintest touch of admiration. But before I had time to bask in what I could only take as a compliment, he then casually proceeded to one-up me.

"But not as cynical as me," he declared flatly, thus putting the matter to rest. His gaze then returned to the road – where far beyond the horizon, Mother Nature had laid down a series of frightening physical challenges that were there to be met – and hopefully survived, if not actually vanquished – by a rare breed of men and women – adventurous, self-motivated, and resourceful - one of whom was none other than Athol Whimp, his own bad self.

The difference between SAS selection and Himalayan mountaineering, he once told me, was that during selection you knew you weren't actually going to die. Secure in that knowledge, he'd duly made it through when he was barely out of his teens. At the end of two torturous weeks – by which stage he'd lost all sense of time anyhow - he'd been ushered into a room where an officer coldly remarked: "Well I suppose there was no way you were going to fail with a name like yours." Nine months later he was a Captain.

But, as author Greg Crouch once said, the world was quieter then. The New Zealand SAS were deployed sporadically throughout the 1970s and '80s. Afghanistan and Iraq, with all their controversies, lay some way off in the future. Athol's life consisted of training exercises – in New Zealand itself, and Fiji and Western Australia. Some of the people he trained with – rather amusingly – even went on to become famous. You know, like Governor General of New Zealand famous.

But it wasn't quite what he signed on for. So, by various machinations, he found his way to Oman and was selected (by some Englishmen, also employed by The Sultan, who'd been tickled by his name) for the Oman Reconnaissance Force. He'd arrived to take command of his soldiers – some of them former insurgents the government had wisely provided with jobs – without any knowledge of their language, his men no knowledge of his. He learned quickly. A few days were spent spray painting modified V8 Land Rovers in camo, then they headed into the desert - The Empty Quarter, The Rub' Al Khali – an enormous expanse of dunes first traversed in antiquity by caravans carrying frankincense - and latterly, intrepid Englishmen like Bertram Thomas, St John Philby, and – most famously of all – Wilfred Thesiger.

Athol never got the glory, but he did manage to one-up his predecessors in the technology stakes – he had an early Sony Walkman – and whenever I hear Hungry Like the Wolf, I think of him charging through the dunes. Workaday life consisted of apprehending smugglers, chasing foreign nationals back to their side of the border, and settling tribal disputes. But to the west lay Yemen, a failing state, prone to erupting with sudden, incomprehensible violence. Years later, he looked up his old haunts on Google Earth and could still see his tyre tracks in the sand.

It was, no doubt, a life you could easily romanticise, especially from afar. He once told me, though – on a rooftop in Melbourne (an environment where he spent a great deal of time in his capacity as a property developer) that it might just have easily driven him to drink. He took furloughs in nearby towns, where there were nurses. On another occasion he did a mountaineering course, and that, of course, changed everything.

He'd already been going into the mountains back in New Zealand, but this time it was serious. He was midway through his twenties at this point; a late starter perhaps. But if Athol had one favourite expression – apart from "get a real job" (liberally applied to parking inspectors and bureaucrats) – it was "The Golden Age of Climbing is Now." I think he may have borrowed those words off a friend, but he quickly made them his own.

His time in Oman had ended rather abruptly. He'd caught a Freedom Bird one way to Bangkok with nothing more than the fatigues he'd been wearing in the desert. I never did ask him why, although a disagreement with a superior would be my first guess. After that he became his own boss, with no one to disagree with other than himself.

He'd taken a cab into the city with a pair of British mates, who now wanted to get stoned. They asked the driver where they could get some chuff and - rather amusingly – the driver pulled over and proudly displayed a whole boot-load of the stuff. Ha! Athol wasn't one to get wasted; partying wasn't his style, he had goals to pursue. But now that he was a civvy, it did rather look as though The Counter Culture was closing in.

And so he became a climber. By the time I met him he'd already established himself as one of the leading Kiwi alpinists of his era. Hardly surprising really, considering his mission statement - which was "If you think you're hard, it's useless unless you're doing the biggest, hardest routes." History doesn't record what he thought about bouldering! I think it was HB - of Taipan Wall fame - who introduced us. We'd met up in a cafe where the staff were being subsidised by the government to get them off the dole, a very un-Athol place, because he had an almost visceral distrust of socialism. But that just underscored how contradictory he could be. And besides, a climber is a climber is a climber: it was the cheapest joint in town.

He'd just come back from Patagonia, where he and Andrew Lindblade had done the Pedrini Route on Fitzroy and the Compressor Route on Cerro Torre. Andrew had to head home, but Athol stayed on, and — in fulfilment of what was clearly a long held ambition — repeated the Torre route, this time solo. He told me this with great politeness, but it was clear the best parts were being held in reserve; we might have come from the same country, but he wasn't melting anytime soon.

One of the anomalies of our situation, however, was that even though he was older, I'd actually been climbing longer – which made me, I guess, something of a relic. So I'd met people he hadn't, people who no longer walked the earth. One of whom was Bill Denz, another renown Kiwi, who'd nearly achieved the first lone ascent of The Compressor Route back in 1981, until an incoming storm and a 30 foot fall onto a stopper persuaded him to save himself for an upcoming trip to The Himalayas – a trip which, sadly, turned out to be the last he ever went on.

Athol would have already formed a deep impression of Bill's character, of course, simply from repeating his routes in New Zealand, which were pretty much the biggest, hardest things the '70s had to offer. Athol thought he recognised a kindred spirit.

Which he did. But there were differences! On one hand there was Athol, who'd done OK in the army – in spite of a highly individualistic nature (this was a guy who'd seen The Fountainhead, his identification being not so much the philosophy as the fact that the lead character was an architect, the only profession he ever coveted more than special forces soldier). Then there was Bill, who'd quit the army partly to quell the derision he was getting from his long-haired climbing mates, and who spent the next decade chasing that forever receding horizon - "The Last Great Problem" - all the while subjecting himself to some of the more interesting altered states known to man.

I'd met Bill at Mount Cook – no snob he – and we saw in 1983 at a New Year's party in the village dancing to Abba, The Bee Gees, and KC and the Sunshine Band. He also had a serious side that really appealed. His attempts on The Compressor Route had been epic, and the letters he wrote in camp (excerpts of which subsequently appeared in the NZ Alpine Journal in 1983) were infused with a near mystical fervour. "God has my number engraved on a marble," went one, "and I shall not pass beyond this physical world until he chooses to roll that marble out. At any rate, I am taking no chances and am conducting my life with more respect for nature, the elements and other people than ever before."

Even then I could quote most of it off the top of my head, which I proceeded to do for my new friend opposite. You'd think it was some far-out free association Bill had sent back to his waster friends in Yosemite. But it wasn't, it was a letter home to his mother! Athol got it immediately. Maybe there were some deeper implications there, but to us it was just the epitome of small town New Zealand, which is all small town really. Tight knit families and healthily nurtured offspring.

But – as the song says – "all boys must run away" and on the occasions when Athol himself was back at home, he'd display his independence of mind by, for example, telling his mother that he was thinking of soloing K2. An old school South Islander, whose treasured possessions included an ice axe, she would have had no illusions about how this could turn out. But you can't expect your children to live wrapped up in cotton wool.

We started hanging after that, though his moods were like mountain weather. The guy was a workaholic, an unabashed capitalist. No matter how much fun it was reminiscing about the characters back in Mount Cook Village (Nick Banks, wherever you are – hi from both of us!), you always got the feeling of the meter ticking. I remember sitting down next to him in a cafe one afternoon – late, no doubt - and the first thing he said was: "You ought to hear what these fucking idiots are talking about."

"What fucking idiots?" I asked, looking around the room – until two pairs of eyes in my peripheral vision brought me back to the now very pissed-off couple at our side. Ha! Poor Athol! He'd overheard their conversation and it turned out they were arts bureaucrats, i.e. recipients of public money. The hardest thing in the world to understand, as Einstein famously said, is income tax – and Athol could never get used to it. It made for some really awkward moments. I consoled myself that it was probably OK to have one "worthy arsehole" as a friend – just as he no doubt consoled himself that socialising with useful idiots like me was a cross he was just going to have to bear.

Globalisation was the buzzword back then, and it suited Athol's agenda to mount an assault on the biggest unclimbed faces in the world, all from a base located in the flattest, most isolated place going (but don't forget Taipan Wall and Arapiles!). The "tyranny of distance" didn't bother him. He could afford a taxi to the airport anyhow (not like you or me!). He and Andrew went to the Gangotri a couple of times, the second time successfully, the object being the coveted North Face of Thalay Sagar. There wasn't a whole lot of compromising on that particular trip - Andrew once described Athol as a "supreme alpine purist" - and the tactics they employed reflected this. There's an article in an old Rock Magazine (a charmingly irreverent quarterly that flourished down here in the days before climbing bans), one of the few Athol ever wrote, in which he mentions that he's leading "on two 100 metre, 8 millimetre diameter static ropes" - which prompted the worried editor to warn his readers that this was a "significant compromise in safety prompted by the unusually demanding route - not recommended!" Well, it wasn't like every one was suddenly trying it at home.

Athol must have been cajoled into writing something in return for some kind of modest sponsorship deal, and it was certainly intriguing to see him open up a little. Typically, one rounded off a piece with a brief self-written bio, and Athol's was one of the most colourful they'd ever received. It read "Athol Whimp, 36, lives in Melbourne where he is a property developer in his spare time between expeditions. Originally from Christchurch, New Zealand, his early career in the army culminated with his personal stand against communism in the deserts of the Middle East. He says that his strong commitment to mountaineering has had an adverse affect on his ambition to become a millionaire."

It was one of the hardest routes climbed in the Himalayas that year, and when they arrived back in Australia, Andrew and I went out for Singapore noodles at a local restaurant. No ticker tape parade for them. In Australia, that was only reserved for those who'd reached the summit of Everest, irrespective of the style.

But the rest of the world noticed. They won the Piolet d'Or, the mountaineering award given out by Montagnes magazine and The Groupe de Haute Montagne. It was something they'd neither "coveted or expected", certainly not when the greatest prize was survival and when, in Andrew's words, they'd given everything and got everything back in return. But a golden ice axe was better than antipodean indifference. Well...that's a little unfair I guess. New Zealand, naturally, has always harboured some kind of climbing culture – this is a country that has a mountaineer on a banknote (Ed Hillary, $5 bucks. Apparently he used to hand them out to his family at Xmas!).

Australia, however, despite going on about how "sport is our culture", can barely recognise alpinism in any form, so if you've just come back from "the death zone" and you're planning to catch up with some friends over coffee, don't be surprised if the footballer who's been making headlines for posting inappropriate material on Facebook gets a table long before you do! The humiliations don't stop there. Athol and Andrew's next objective was The North Face Direct on Jannu, for which they needed a letter from a recognised body to prove they were legit. There were only a few Australian outfits with the standing and they were more than willing to write a brief reference, all for a small fee (three figures, naturally)! As if it wasn't hard enough to organise expeditions Down Under anyhow. Athol declined, got a reference from the Federal Minister for Sport – at no cost – and a Golden Ice Axe too, whatever that meant, although, as it subsequently turned out, it meant a "rowdy, fun award ceremony in a Chamonix bar" and a day on the slopes, with Athol remarking that they "had to ski with consummate style now that they were in the sort of place James Bond would have skied."

Athol had already shown me the route they were going to try. He had an enlarged photo of it in the boot of his Mercedes. We'd just finished painting the facade of a building belonging to Melbourne University with anti-carbonation paint. It was a classic high access gig - too high for ladders - so we'd utilised a cherry picker and, being climbers, we'd even at one point stepped across the void onto the second storey of the building. But it just so happened that when we did, an off-duty Work Safe Officer was walking past. Athol, who firmly believed that one should commit at least "one act of anarchy per day," went down for the inevitable showdown and came back about ten minutes later muttering that "no civilian" was going to tell him what to do.

"But isn't that how it works in the military?" I asked. He wasn't listening, of course.

After we'd finished, we ended up beside his car. Athol was still talking about the trips he'd made to Japan to pay homage to the architectural works of Todao Ando, the so-called "poet of concrete." He'd even gone down to Osaka to see Ando's office and while he was there, who should walk out the door but Ando himself! Think the SAS are hard? Athol had been too shy to introduce himself!

"It's called stalking," I said, but he was already popping the boot. And there it was: Jannu, North Face Direct. It seemed a strange place to keep it, but then again, maybe he didn't want to look at it too often.

"What a big, frightening thing," he said gravely. Silence. There was no mistaking the steepness of the final headwall - or the fact that it didn't even start until the 7000 metre mark. Someone was going to have to go up there, and it wasn't going to be me.

Rock Magazine got an article out of that one too (the Whimp autobiography, BTW, was never really on the cards – he was a doer, not a writer, although I don't doubt he would have quite happily paid someone to do it, rock star that he was). In fact, he nearly didn't make it home to write anything. Their portaledge had been destroyed by rock fall at 6000 metres while they were still in it – although, incredibly, neither one was hurt. But the North Face Direct was finished and even as they were preparing to go down, they were already looking over at The Wall of Shadows, the next route along, planning an alpine style ascent. They spent some time recuperating and then went for it, leaving – as he wrote in his article without any detectable emotion - a note amongst their gear "should we not return."

But return they certainly did - a week later - although they'd been forced to play "Russian roulette" with towering, unstable ice cliffs that threatened the route in its lower reaches. The challenges didn't stop there; 100 metres from the top, Athol began to notice a "crackling, buzzing noise" - static electricity - emanating from his helmet. They quickly retreated to a conveniently located crevasse, where the overnight temperature dropped to -20. They summited the next day. Throughout their ascent, they'd been afforded "stunning, close up views of the stupendous headwall of the North Face Direct" - their original objective. They speculated on how they would have gone, with Athol commenting that the "enormity and complexity of the head wall" left them almost speechless. It would have been an interesting place to hang a tent.

I remember when they got back. Andrew had lost so much weight he looked like a favourite jumper that had been put in a clothes dryer on a "high" setting: everything was the same – only smaller. He moved to New York not long after that. I never did find out why – a good job perhaps – or maybe he felt he'd been on the wrong side of the line a few too many times, and wanted to put some space between himself and the Australasian mountaineering community.

But if he thought he was going to get some sleep in "the city that never sleeps," he was wrong. You had to hand it to Athol, he was persistent. Indeed, it never ceased to amaze me how, no matter the dreariness of the surrounds, he always managed to talk me into joining him on one of the inner city roof tops where his time was mainly spent. I mean, it was just me and him up there – and a whole lot of rusting building utilities - but chances were it'd be a lot more entertaining than anything else that was happening that day.

New York probably provided tougher competition, although for a certain type of individual a strong pictorial cue would probably cause their workaday life to unravel in just a matter of seconds. Nowadays the preferred medium is social media, but back then Athol was still using postcards. Andrew subsequently reproduced one of these in a self-published book called "Adventures with Athol Whimp" - and when I finally saw it, recognition was immediate, because the mountain in question had been the screen saver on Athol's lap top since forever.

Predictably enough, it was a near symmetrical Himalayan pyramid, twin summits glowing in the dying rays of the sun. The Shining Wall of Gasherbrum IV. Oh, he was obsessed all right – as only he could be: I remember once he asked me for a definition of "non attachment" - which was weird, because people who lead lives of managed risk probably know better than anyone the tenuousness, the sheer futility of trying to hold onto anything. And yet there it was: only deep attachment would cause them to pursue such lives in the first place.

I shrugged. About the only thing I could think of saying was "Well what it means is that we're all basically plankton" - infinitesimally small and no grip strength whatsoever. Not much chance of staying attached.

The obverse of the postcard is worth quoting, 'cos it reminds me of why I've seen so many more high rise water towers and air conditioning units than I ever expected to see:

"Andy," reads the card, "sunset on G IV! Imagine being up there on one last bivi before the summit, digging a ledge for the tent, watching the sun go down. Fuck! We should have the most amazing trip ever - mind you it is pretty hard to top Thalay + Jannu. I still don't know which route – they are all awesome. But the West Face....Get psyched dude!" All written with the alacrity of a man inviting a friend to a music festival, even though they both had roughly a one in ten chance of not coming back.

We talked about this over coffee. "It doesn't take much," he said, referring to how quickly things could go south on a route.

"Don't go," I said reasonably. I mean, if anyone had earned the right to expire in a warm bed at the end of a long happy life, surely it was him. He said something like "I love life – but this is what I do" and I think it was at this point I began to realise that there probably wasn't much chance I'd see the money he still owed me, ha!

He'd kind of nailed it though, 'cos back in those days, if you loved life – in the sense that you liked the wind in your hair, or the thrill of the chase, or the sharp adrenal surge that accompanies danger – then chances were you'd end up a climber, 'cos what better life is there? And the history of the sport becomes ever more compelling the deeper you get into the thing. Certain high points stand out: one of which would have to be The Shining Wall of G IV. The way Athol talked about it, it was like the first ascent had been done by seekers on a mystical quest, the stuff of legends.

These days, of course, you can read the original account on your phone, although none of the mystique has been lost: the writing is, by turns, concise, factual, and poetic – the latter being the perfect vehicle for dealing with out-of-body-experiences, disembodied spirits, and a mountain (an inanimate lump of stone, surely?) that possessed a conscious awareness of – and a malevolent attitude towards – the puny beings clawing their way up its side. Not too many people have passed that way since the first ascent apparently.

I wondered how Athol – a staunch rationalist - would go as he inched ever higher into the interface between the corporeal world and the supernatural one, although I remember once he told me that his atheism had wavered somewhat in the face of the Italian art he'd seen in The Met in New York (Caravaggio, in particular), which certainly revealed an unexpected susceptibility to religious propaganda. Maybe he'd turn into a bird up there in the upper reaches of The West Face – although, being Athol, he would have acted as though this was what he'd been planning all along.

But like so many expeditions to the Greater Ranges, their trip was thwarted by nothing more or less dramatic than the weather. The pictures he managed to take all attested to the committing nature of the climb – they were un-roped a lot of the time, and decent bivouac spots were almost non existent. They did, however, have the satisfaction of knowing they were some of the few people who'd ever been up that far – no mean thing in an over-crowded world.

They had do some pretty hairy down climbing to get back. "At times," wrote Andrew, "we would look into each other's eyes...and it felt like our very beings were evaporating."

But back you must come, 'cos freedom is only fleeting, and there are always more bills to pay.

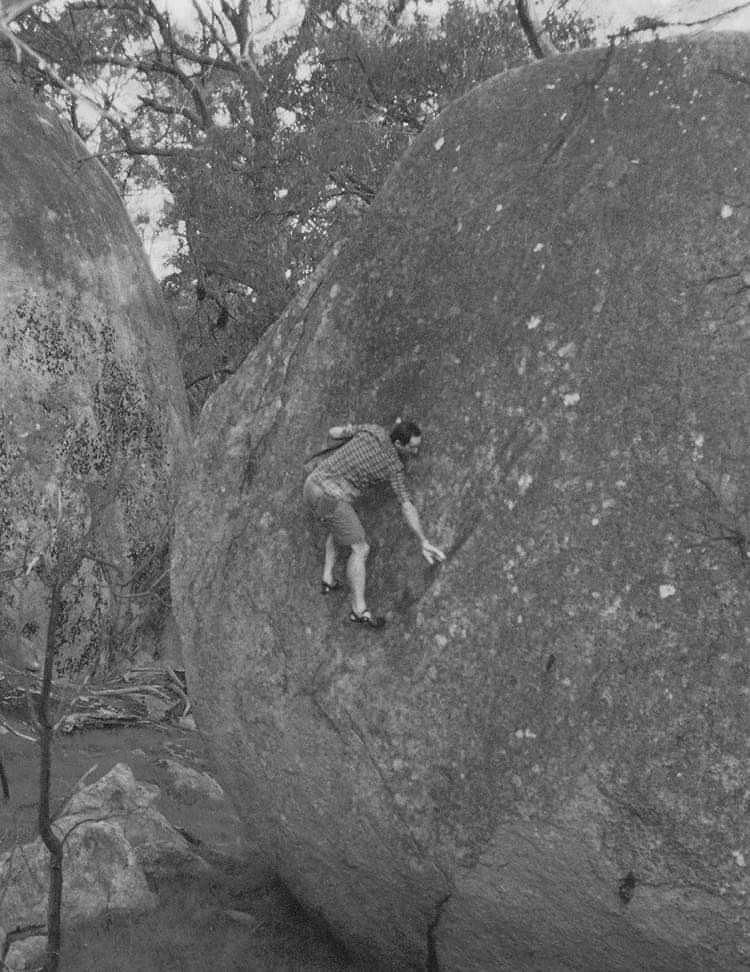

Indeed, in the years following this – the last of their great expeditions - Athol worked so hard on his property business that his climbing dried up entirely, which was incredible really, 'cos I'd always figured him for a lifer. Sensing he was vulnerable, I got him to come bouldering, which was a bit like getting an All Black – M'aa Nonu, for example - to come and play touch rugby (the massive, dread-locked Nonu being one of Athol's favourites - "I'm not gay," he'd claim, "but I'd put product in Nonu's hair.").

And so we went out to the area loosely known as The Goldfields, a series of granite tors north of Melbourne. Not world-class, by any means, but not a world-class pain in the arse to get to either, which is always a plus in Australia. He kind of damned the activity with faint praise. It was "great fun," he said, which, given that most of the activities he deemed worthy were more or less exercises in extreme suffering, really gave the game away. I'd be topping out on some 6 or 7 metre granite egg, and I'd hear his voice casually informing anyone else present (gym aficionados usually, none of whom could believe that boulder problems ever got so big) that what I was doing was "not real climbing."

Well I'm not Mahatma Ghandi either, so a number of times I burnt him off on highballs to which he wasn't game to commit, and I was like "What's the problem – too unreal for you?" Ha! But the chemistry made me climb like I hadn't climbed in years and he was the one of the lowest-maintenance partners I'd ever had: just boots and chalk, and never a word of complaint about a 10 minute uphill walk to the next problem. We were also united in our disdain for boulder pads, which were obviously a sign of cowardice, but it so happened that towards the end of his life he reconnected with his erstwhile sponsors, Metolius – and when they heard he'd been doing a bit of "pebble wrestling," they offered him one of their finest mattresses! To which I could only respond "Can you get two?"

We hung out lots in the end. I'd reached the age when there were no "special" people in my life, only those who caused the least amount of trouble, a category which he kind of conformed to, with the proviso that the trouble he did cause was often – at the time – or even better, in retrospect – very entertaining ("Charles, I need you to give me an alibi").

And yet for all his cynicism, his tendency to default back to an insistence that there was no type of behaviour whose root cause couldn't be traced to a desire for money, status, or power, there were times when his personality would dramatically flip poles. We were in a cafe and one of the staff was – well, if I say "odd" I'll be in trouble for being non-inclusive, so let's put it this way: their idiosyncrasies were basically the first thing you noticed. Which caused me to remark, in an undertone: "Christ, you wonder how these people ever find partners."

But Athol was having none of it. "No Charles," he said sagely, "there's someone for everyone." I just stared at him. WTF?!! "Who are you?" I thought – "and what have you done with my friend?"

Indeed, life's rich pageant never failed to elicit a thoughtful commentary from this most astute of all observers. One day we were talking about people who regret tattoos and Athol looked at me, an evil glint in his eye, and said "Do you think Charles Manson regrets that swastika on his forehead every time he goes before the parole board?" Another time we were some place from which one of those awful university orientation groups had just decamped – and someone had left a copy of the uni paper. We leafed through. One's first few weeks of term, announced an earnest editorial, were a great opportunity for freshers to experiment with different "lifestyles." Lifestyles – what did that mean? Binge drinking, ship modelling, writing romance novels – dare I say it – rock climbing?

Athol, however, was adamant it could only mean one thing: "girl on girl action" (no doubt it meant "boy on boy action" too – but I wasn't about to raise this with someone who'd just spent long years in the army). Not that you'd get him on campus. The one time I succeeded, I'd been eyeing some off-cuts in a skip and had convinced him to tag along, all he did was bitch about the place being a refuge for tenured mediocrities who had no idea how the real world operated. Probably what Plato had in mind, now that I think about it!

I remember the day in 2011 when the news broke that Walter Bonatti had died. Well this wasn't exactly headline material in parochial Australia, but I figured I knew one guy who'd be interested, so I let him know by email. He was stoic as always. His return email read "Very sad - but what a life! Standing on top of Gasherbrum 4!!" To which he added "I checked - no worthwhile rugby tonight."

Dang! That meant Australia was playing. It was World Cup year, the tournament was being held in New Zealand, and the All Blacks – who'd gone into every World Cup as favourites – were at the end of a 24 year losing streak. Talk about a hoodoo! I wouldn't say we were rugby tragics exactly, just a pair of ex-pats looking for a way to express our loyalty to a country that neither of us wanted to live in. The All Blacks were in an awkward position - winning at home wouldn't vindicate them entirely (Christ, even the Wallabies could win at home occasionally), but losing in front of the assembled fans simply didn't bear thinking about.

The pool stages were a blur - high speed walkovers against lesser teams - none of which mattered if you never got to grasp the trophy. But they were fun to riff on. I remember watching a young Australian nearly having his career ended by just one tackle, and surmising out loud that if he could survive that, then he probably had a great future. To which Athol – who'd played rugby against the Fijian Army, and who could probably still feel it on cold nights – replied "Yeah – as a librarian!" Ha, in a world where mainstream sport is so unashamedly brutal, why is it so hard to explain climbing to the layman?

We made it into the finals, of course – NZ vs France at Eden Park in Auckland. I remember walking into the city that night: the prevailing code in Melbourne is Aussie Rules, so there was no outward sign that a major sporting event was about to get underway. Every English and Irish themed pub, however, had a crowd outside and it was in one of these places I found Athol, comfortably ensconced with a good view, his jacket draped over the seat beside him. That one was for me. Well if that's not friendship, then what is? And looking back, it still seems incredible that he was just a few short months from the end – although this was a guy who once said – of mountaineering – that he'd rather die than fail – so if I figured I knew something about non-attachment, then I was soon going to get some practice.

But if fate robbed him of a big chunk of his life, there's no doubt that the way time dilated in the last 20 minutes of the 2011 Rugby World Cup Final made up for it to an extent. What did Einstein say about putting one's hand on a hot stove? One moment feels like an eternity. That's relativity. Watching the All Blacks defend a one point lead - against the team that had shattered their World Cup hopes not once, but twice - was like several eternities in a row; a generous deposit in one's allotted share of Earth Time, to be sure, but with the caveat that it was only to be spent in a most uncomfortable way.

Athol was more of a Kiwi than I realised. The All Black scrum was beginning to wilt, which was hardly surprising really, 'cos being the team with the most to lose, they didn't want to get penalised. But it was like taking a long fall: you know the rope is designed to stretch, but there are times it stretches way more than you can bear. Athol, it seemed, had had enough – he suddenly got to his feet.

"I can't watch," he said. I forced my eyes away from the screen and looked at him, totally bewildered by this unexpected turn of events. This was the guy who'd willed himself through SAS selection by clinging to the thought that no matter how excruciating it was, it still had to come to an end eventually.

But who wanted to see New Zealand choke in yet another World Cup?

"I'm going outside," he said urgently.

"How's that going to help?" I asked. After all, it would have been all but impossible to refrain from peeking through the window every time the crowd went into hysterics. And God - I didn't fancy watching the rest of the game on my own. Fortunately, he sat down again.

And ultimately the game did indeed draw to a close. And when it did, we were still one point in front - a margin that certainly didn't do much to prop up the myth of All Black invincibility. But a win is a win is a win. The whole thing had affected me quite profoundly: my pulse was up and my forehead hot to touch. Graciousness in defeat is nice and easily afforded by a losing French side that only had to head home to enjoy one of the most enviable lifestyles known to man. But what did a losing Kiwi side have? Three small, windswept islands on the bottom of the world. It didn't bear thinking about. With the final quarter to go, we'd been caught out on the wrong side of the line, and only sheer grit had gotten us back.

But was it sheer grit? Maybe it was something else – a higher force perhaps – and maybe I ought to be paying my dues to that force. Who knew? I did know one thing though: I wasn't going to take any chances. I was now resolved to conduct my life with more respect for nature, the elements and other people than ever before. Christ, maybe I could even bring myself to be a little more patient with non-climbers.

I guess you could say I'd had an epiphany. I tried to tell Athol, but his expression – which only moments before had been one of un-self-conscious joy – had already reverted back to the habitual gnawing hunger that drove him, that was always going to drive him.

"2015," he was saying fiercely, referring to the next World Cup, "let's go back-to-back." Of course, I realised, a second World Cup victory in 24 years just wasn't enough – we had to keep winning. Like I said, he was competitive.

We did go back-to-back actually, but Athol wasn't there to see it. This isn't really the place to dwell on that – and where would that get us anyhow? But I do know a great epitaph for the type of person he was – a climber - that unique mutation of the human form that slowly began to evolve when the first dreamers started looking up at the flanks of Mont Blanc and thought they detected a line. The epitaph comes from Yosemite's Jo Whitford, a woman who's known a few individualists over the years, and who, when speaking of a late contemporary, described him as "intelligent, kind, arrogant, bitter, and very hard to know." And – crucially – no matter how difficult he could be - "we all wanted to be him."

Indeed.

Athol Whimp, mountaineer.

With thanks to Andrew Lindblade for the provision of photos. Visit his website.

Comments

Logging in for the first time in a while to say thank you - superb!

John

By coincidence, I've just this week finished re-reading 'Expeditions' by Andrew Lindblade and Greg Crouch's "Right Mate, Let's Get on With It" article about Athol. Both of which I found, along with Charlie's thoughts, to be excellent.

Cheers Charlie

Enjoyed that so much. We had some great days out together from the Port Hills to Arapiles to Mt Cook in winter.

Couldn't sleep and just got up at 6:30 because I was so excited about the prospect of taking off to climb on an old WW2 bunker in the woods north of Berlin today; I was sitting with a coffee and the first cigarette in the early backyard sun, and then I read this. It's made my day already; brilliantly written, many thanks!

Wonderfully written! Thank you...