Reverend Bob Shepton is not your average 82 year-old. He has filled his long and interesting life with climbing, sailing, church ministerial duties, youth work and military service in the Royal Marines. Since retiring, Bob 'left the pulpit for the cockpit'; not to live a life of leisure and luxury on a yacht, but rather to make lively sailing and climbing trips to Greenland with renowned Belgian/American climbing quartet, the 'Wild Bunch' - Nico and Olivier Favresse, Sean Villanueva O'Driscoll and Ben Ditto - which have earned Bob legendary status thanks to the critically acclaimed films of their antics: Vertical Sailing Greenland and Adventures of the Dodo's Delight. He's no leisure sailor, and don't even make mention of a marina...

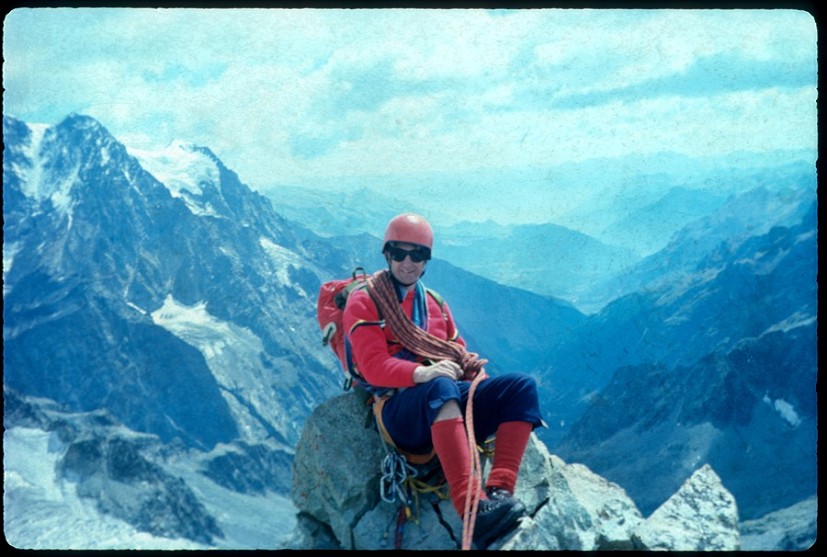

Having been fortunate to join a team skippered by Bob on a sailing and climbing trip to St Kilda this June, I took the opportunity to interview him on his beloved Dodo's Delight, a 33ft Westerly Discus sailboat that has many a tale to tell. Greenland, Arctic Canada, the North West Passage – its size is no indication of this boat's gutsiness, nor that of its skipper, who has been lauded as 'an institution in Northern waters' and duly received the Yachtsman of the Year Award in 2013, as well as being a two-time winner of the Tilman Medal. Bob's crucial role in the 2010 Greenland new routing expedition also won him a Piolet d'Or in 2011 as part of the 'Wild Bunch.'

In between my watch duties and when Bob wasn't making cheese toasties, asleep in his bunk, or fulfilling other important tasks as skipper, we found the time to see if he really is - as the title of his book suggests - 'Addicted to Adventure.'

'My publishers suddenly asked, "Well, could you explain why you do all these things?" and so I had to stop and think, "Well, why do I do them?" and I quickly concluded that it was the challenge element that was the great attraction for me. I didn't go up the mountains to enjoy the view or the technical side of the climbing. That was part of the challenge, but it was always the challenge that was the main motive, and I suppose that's part of adventure, really, the challenge, and so forth. But how did we get on to that? I've forgotten.'

OK, Captain Bob. Going all the way back to the beginning - where were you born and where did you grow up?

Well, I was born in Malaya in the days of the colonies. This was before the war, obviously, and then in 1940 we were sent to Australia because our education wasn't going very well in Malaya. Then my mother came out, I think ostensibly to take us back again, but then the Japanese invaded and my father was caught on the rubber estate – he was the manager of a rubber estate – and they had no use for prisoners so they shot him and the guy who was with him, and carried on down. So there we were stranded in Australia, but my mother was desperate to get back to the UK, so in 1941 we must have taken ship across the Pacific, via the Panama Canal and New York. Very, very cold, I remember. My first experience of putting my hand on cold iron and, oh, it really hurt! I remember one of the seamen trying to, just for fun, teach me how to unravel knots in a rope, on what I suppose was the foredeck of this cargo vessel. I don't really remember anything of the Panama Canal. I just remember New York and how cold it was and these skyscrapers, of course, which I'd never seen or experienced before.

So we joined an Atlantic convoy and came back across the Atlantic, and two boats were torpedoed behind us which I thought was great fun but, in fact, myself and another boy were not very popular because we used to run around the boat and make a very realistic copy of the siren noise. Anyhow, we arrived at Avonmouth, in the beginning of 1942, and had no money at all because, obviously, father was missing, believed dead, but we didn't know for sure so nothing could be tied up for ages. But he had bought an orchard in Essex, I think, and that was sold by auction, so at last we could buy a house instead of living with my aunts. Then I stayed in the South of England for most of my life, really.

Did you experience much of the war there?

It was strange, yes, we did in the sense that it was a doodlebug area, and in a way they were better because you had the engine noise and then it cut out, and then you waited for the explosion and if it wasn't on you, you were okay. The V2s were much more frightening in that you had no warning and suddenly there was an explosion and a V2 had arrived. So we were in that era of the rockets being sent over to bomb London and so forth. We missed the actual Blitz, though I do remember that when I first went to Carn Brea, which is a prep school, we had been sent off to Cranleigh and given some space in Cranleigh School, so we were evacuees from the London environs into the country. I didn't see anything really of the Blitz as such.

Do you think your unsettled childhood (travelling around in wartime, and attending boarding school) prepared you to lead an adventurous life?

I don't know. I think that's perhaps a bit early, but I suppose it had unconsciously inculcated it. I never settled in one place for any length of time and, of course, then I was sent away to boarding school, so that perhaps added to it. So the sort of settled, peaceful 'in one place' existence, I'd had no experience of that and so it wasn't part of my psyche or whatever the word is! Changing places, scenarios, projects, people is not now unsettling. To stay a long time in one place is boring or difficult.

Where did you go after you had finished boarding school?

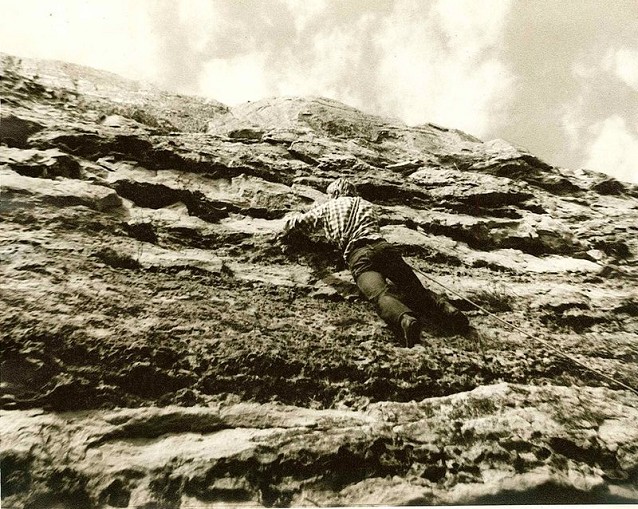

I think that was a more formative time because it was the days of National Service, and I did it in the Royal Marines and then the Commandos, and was sent out to Egypt, Malta and desert training in North Africa, and in the end did the Cliff Leader course, which is now called Mountain Leader in the Royal Marines, which gave me climbing as a hobby and passion for the rest of my life. I suppose the sort of public school attitude and then the Royal Marines inculcated this love of challenge and adventure.

Since I'd been to Christian camps and had made a committal to Christ, as it were, and become a committed Christian, I had this idea that maybe I was meant to be a Reverend, but I wanted to do six to seven years in the Royal Marines and then think about that. But it's typical of me that I hadn't actually discovered until I got in that if you started as a Marine at Lympstone, then you went away to a War Office Selection Board and then officer training, and then you came back into the Marines as an officer. In those days you either signed on for the two years of National Service or you signed on for 22 years, and there was nothing inbetween. I didn't think it really added up to sign on and then buy yourself out in six or seven years, so I just did the two years, in fact.

Then I was a Royal Marines officer so I could do anything, you know! So I turned up at Cambridge and had an interview and the first guy in Emmanuel College said yes, he would take me as long as I read Theology. Well, I thought Intellectual Theology at Cambridge would probably be more deadening than really enlivening, so I didn't take that place, but fortunately I had a friend through those camps I'd been to called Mark Ruston, who was rector of the Round Church in Cambridge, and he had been to Jesus College and so had links there. So he took me along to whoever was the admissions officer in Jesus College and we had an interview. I had been captain of football at Bradfield - I think this probably counted for more, and I was a Royal Marines officer, of course, and so yes, I got a place!

You say you found this passion for climbing. Did you do much whilst at Cambridge? How did you progress after your university studies?

Actually, no. I did join the Cambridge University Climbing Club, but I didn't really do much. Later I got this passion for it and then eventually I went to theological college at Oak Hill in North London, and ended up as a curate in Weymouth on the South Coast. And I remember saying to the Lord, "Look, this is fine, but, you know, there's absolutely nothing to climb around here at all, but this is where you want me?" And then I read an article by Joe Brown about climbing limestone at Malham Cove and I suddenly realised, "Hey, there's all these limestone cliffs around here." So I started to develop the limestone at Lulworth and Portland, and used to take the youth group along of an evening when we were meant to be in the church building doing whatever…but instead we went to the cliffs and climbed these routes. I must have had about 10 years when virtually nobody else, or very, very few people were climbing these cliffs, so I just had it all to myself.

It's humorous nowadays, but I remember there was a couple up in Dorchester who turned up and we did a deal that I wouldn't climb in The Cuttings and they wouldn't climb on the sea cliffs. I could just imagine that happening today, negotiating that you were going to be left exclusively climbing the sea cliffs and kept off The Cuttings and so forth. I had a great time and did a lot of new routes on the East Coast, first of all, and then on the West Coast, which was more serious. I left the West Coast because it was bigger and I thought it was probably fairly loose. Actually, when I got there, it was pretty good, though I was disappointed years later when they turned these three miles of magnificent limestone cliffs into a sport climbing centre and started to bolt them. They did agree to leave the trad routes, but I'm not sure they've actually kept that agreement completely. Wallsend Wall, I remember, was one of my favourites. It's about E1 or something, which was pretty startling for me in those days. EBs, and we did have chocks and wires by this time, but no cams. I think now they have put a couple of bolts there which is slightly disappointing really. I was sorry that they turned it into a sport area, and they kept Swanage as a trad climbing area.

I found that I was a legend in my own lifetime in the guide book. Well, first of all I wrote the guide book for the 1978 climber's guide, and then Steve Taylor has written an excellent guide now, and I'm in the historical section, you understand!

You must have had some quite exciting experiences on new routes on limestone?

That's right. The final climb we did there, which I think I called Grand Farewell, because it very nearly was - it was about E1 and it came up a little wall, and then there was an overhanging block and I put both hands on the overhanging block to pull myself up and over, and the whole block exploded out of the cliff. As we went down, what I was afraid of was that the block would hit me, but actually the block went down quicker than me and I was held on the first runner, so it was alright. Banged my ankle and it was a bit painful, but of course, I was ex-Royal Marines, so I got back on the cliff and completed the route. So yes, we did have some adventures of that nature!

It must have been quite an exciting period to be climbing. I'm assuming a lot of your contemporaries were people like Joe Brown and Don Whillans?

Well, that's right. Joe Brown and Don Whillans had sort of led the big breakthrough, and then there were people like Pete Livesey and Ron Fawcett. They were coming up and doing routes in North Wales. Yes, it was an exciting era. One or two people went solo climbing, but that didn't go terribly well. The gear was fairly…well, you'd think it rudimentary now. As I say, EBs, we thought they were great but you wouldn't dare climb in EBs these days. We started by just threading nuts on slings and then people started producing commercial nuts. Oh, and I climbed in the Whillans harness for many, many years. Still got it at home, actually.

And then later, I was in North Wales as Chaplain of St David's College, and Rowland Edwards was developing the Ormes and, again, I had the glorious title of Chaplain and Outdoor Pursuits Master, so I used to take them off climbing and we'd do a number of new routes on the Ormes. One of them, I think I called Genesis because it was created out of the earth. There was so much grass on it, which we cleaned out before we actually made the climb. So that was another exciting climbing era. I did some climbs with Rowland Edwards as well, and wrote an article for Ken Wilson on the cliffs, and sort of gave suitable acknowledgements and praise to Rowland and his developing of it and so forth.

'I could just see their minds going, you know, "What's it going to be like? Three months in the confines of a small boat with a crusty old Scottish priest."'

It must be quite strange for you now, as obviously when you were doing new routes there were plumb lines everywhere, which were so easy to find, and now adventurous climbers are having to go further afield to remote islands?

Yes, well, that's it. Of course, something else that has struck me is that nobody had ever heard of bouldering, you know. You might just mess around on boulders for a little bit of practice. And certainly 10 metre routes, you wouldn't really bother with those. They had to be fairly long, but now, of course, with the pressure on new routes, any bit of rock you can climb and claim as a first ascent goes. There's been a bit of a change in outlook on that score.

Do you think when you were climbing a lot, you could imagine the sort of development that's gone on equipment-wise, and also in terms of standard?

Yes. I think the real breakthrough was just coming in as I was finishing, which was 'Friends,' as we called them, i.e. the cams. I think that has revolutionised the standard, really, because when you've got a cam in, you do feel pretty safe. I've actually moored my boat on two cams in cracks at the bottom of Impossible Wall in Greenland, and the boat was quite safe and so were the climbers. Also, the better rubber on rock shoes and the variety of rock shoes you can get, and the harnesses are so much more user friendly than the dear old Don Whillans harness. So the equipment has made a lot of difference to the standard. People are now taking it more seriously, if that's the right word, in that they're actually training continually for this. I mean, dear old Sean (Villanueva O'Driscoll) is stretching with rubber bands every day, and the Wild Bunch, if they're not climbing in some form or another for two days, they're suffering from withdrawal symptoms, whereas it was all much more lackadaisical and amateur as far as we were concerned.

Joe Brown and those guys, they had free beer at the hotel or pub in Llanberis because they were the attraction, so the climbers all went to that pub because Joe Brown and Don Whillans were there, and so they were drinking of a night and then they would be out climbing the next day. I just don't know quite how they managed that, but they certainly weren't into this training regime that people are, quite rightly, into these days.

So how did you get into sailing? Where did that come from?

That was something I worked up with the schoolboys as well. First of all, we had this cottage on Portland, but used to go down occasionally as a family to the harbour, saw all these boats and thought, "Oh, that would be a nice family thing to do." So when we were in Glencoe, I bought an old wooden pilot cutter, probably from a battleship like the Vanguard or something, converted to a gaff ridge ketch. So there were all sorts of lines and things to pull and to learn, and so we started to sail round the west coast of Scotland in Far Away, this converted pilot cutter, and it was a big adventure for us as a family to sail from here past the Mull of Kintyre down to Belfast, you know. This was a big expedition, as it were. Mind you, there were seven of us aboard, us and five children, and two of them had to sleep under a canopy in the cockpit!

So that was where I started, but when I moved back down to Kingham Hill School on the Oxford/Gloucester border, we sold our house in Onich, near Glencoe and very unwisely from a worldly point of view, bought Dodo's Delight with the money from the house, which is when we eventually realised, "Well, we haven't actually got anywhere to live," because we were in tied accommodation at the school, supplied by the school. My wife had been the District Nurse for the area around Glencoe, and she, being Irish and so Celtic, got to know everybody and was dying to come back to Oban, so we just bought a small stone cottage here, which is now our house. So that meant that now we had a bigger boat, and could, in fact, sail more seriously, but first it was just for a family thing to do, and in those days there were no real sailing courses or anything, so I bought the books and read the books, and we went out and did it and just learned by doing it, really. Then my wife found she got very, very seasick, so that put her off, and the family as they grew up found other things as well that interested them, though they all were quite good sailors, or most of them!

So I began to use it more and more for the school, and in those days, of course, there weren't codes of practice or anything, so you had a free hand. First of all, I just took them across the Channel to the Channel Islands, or Northern France, and then in 1984 was our first ocean passage to the Azores. Then 1986 was the school centenary, so we became the first school to sail across the Atlantic and back, Portland in the UK to Portland, USA, changing crews in America, and so it developed from there really, and then when I retired, we became the first school to sail around the world.

You've been on quite a few pretty exciting adventures since then, long trips. Tell us about those!

Well, yes, that's right, and I suppose by this time I'd got the taste for this sort of adventurous sailing as well as climbing. But climbing had taken a back seat. I mean, there was no climbing involved in sailing around the world or anything. But when I got back, I thought, "Well," you know, "What do I do now?" and I must have been reading Bill Tilman's book and realised that whereas Antarctica - because we'd gone down to Antarctica - was dramatic and majestic and a very attractive place to go, it did take three months to get to the Falklands and then, say, a month in Antarctica and then three months back again. As I was reading Tilman, I suddenly realised that, actually, he used to go to Greenland and do some climbing and then come back in the same summer. So we thought, "Oh, well, we'll do that." So that's how the Greenland link started and, indeed, you could sail across the Atlantic, it would take you about 15 to 18 days to get to Paamiut and then sail up the west coast of Greenland. At that stage it was mainly peak bagging, because there were a lot of peaks that hadn't been climbed, with the occasional rock climb, and then you could come back in the same summer. Then after a while, for various reasons, I started to leave the boat there over the winter and fly back and then fly out with another crew for another project the next year.

And so it developed altogether, including being employed for two separate years on a big super yacht, I think I made 13 visits to Greenland, mainly climbing from the boat, with Baffin thrown in as well.

So how did you meet the Wild Bunch?

Well, that was an adventure in itself, really, because I suddenly got this email out of the blue, if cyberspace is blue, saying, "Well, we climbed Mount Asgard in Baffin last year, and next year" – this was 2010 – "Next year we would like to climb some big walls in Greenland. Do you know where there are any big walls in Greenland?" They had met a guide in the Alps who had been employed by Cristina on the same super yacht that I'd been employed on as the Arctic Advisor. They were employed as guides because she liked to do some climbing, and so they took her climbing in Greenland and Baffin. This guy said, "Oh, well, you must contact Bob Shepton because he's been up there quite a bit."

So that was the reason for the email. So I emailed back and said, "Well, I do know where there are some big walls in Greenland. I've been looking at some for some years now. But I'm not going to tell you where they are because I want them for my own projects. But it so happens I have left the boat in Aasiaat halfway up the west coast of Greenland. What about coming this year?" So they said, "Oh, well, we'll see whether we can raise the finance," and Patagonia and Co funded them, sure enough, and so they came that year. But it was rather amusing really because we had corresponded on Skype, but that was the only meeting we'd had before they flew out. I hadn't actually ever met them and as they got out of the taxi from the airport, I could just see their minds going, you know, "What's it going to be like? Three months in the confines of a small boat with a crusty old Scottish priest." In actual fact, as I then conclude when I give my slide show, the next slide says, "But it actually took them only 10 minutes to discover that it was going to be alright, because the skipper was used to living in exactly the same mess as they lived in!"

So it's been a very happy liaison really and friendship, and we've done two expeditions together to Greenland and Baffin now, and it's all worked very well and it's been a happy, successful time.

It does have its drawbacks, though, because about 10 o'clock in the evening, I would go, "Oh, good," you know, "I can get into my bunk. Now it's time." That would be just the time – because they took all their instruments with them and on the climbs as well – that they would warm up for a jam session, which would go on till one or two o'clock in the morning, and then in the morning, of course, because of my biological clock, I would wake up between 7:30-8:00am, they would still be sound asleep till about 10:30am. So this was a slight drawback that every so often they would have their jam session! But on the whole it worked very well.

You actually did some climbing with them on that trip?

Well, yes, in 2010. They were quite keen that I should do a climb with them. They obviously dropped their standard down a little bit, and by this time we were in the southern area of Greenland. The big wall that they had done was in Upernavik, about two-thirds of the way up the 1500 mile coastland of Greenland, up in the north, in other words. By this time we were in the Cape Farewell area, and as we were passing down one fjord, there seemed to be a wall which was not too difficult and they said, "What about that?" "Oh, okay. Well, we'll give it a try," you know. So I went out with them and it was great in the sense that it started quite easy, and I hadn't been climbing, certainly not climbing seriously for some time. So one got the opportunity to warm up, but about halfway up, this voice came down from above, "Bob? I think this is a little longer and a little harder than we'd actually thought it was."

And indeed it was, because then I went up this sort of a groove and then there was a very nasty move to get over a little roof and so forth, Sean gave me a lot of help with the top rope and so forth, but you know, it came out as E1, E2 or something and by that time I was 75 years old, and I remember arriving completely exhausted at the top and saying, "We'll call it Never Again, Never Again." And that is what we called it, in fact.

What would you say you get out of doing these trips?

Oh, dear, I don't know. That's difficult. Again, it's the challenge aspect, you know. Are we going to manage this? I do get a great deal of satisfaction that the Wild Bunch, for instance, are doing these superb routes. I think E7 was the hardest that they did, but this was a wall of a thousand metres, a really big wall. It took them 11 days to do it. I get a lot of satisfaction out of the fact that they are doing this and they're doing it from the boat, and it was great fun actually mooring the boat against the cliff because the walls go straight down into the fjords so you can get the boat right alongside.

I enjoyed the fact that they made nine extreme routes in Greenland and then in 2014, they made 10 in Greenland and Baffin. I simply enjoy being part of this, really.

What is the attraction of the northern waters and Greenland for you?

Another difficult question. After all, the land is desolate, glacial, without trees but maybe it is its very desolation that is part of the attraction. And its remoteness, and the fact that few boats go up there though that is increasing now, so there is still a sense of adventure. There is very little red tape, still the land of the free, and there are no marinas! There is no buoyage either for instance - it is entirely up to you to sort it all out yourself.

Looking back on your climbing career, what are your most memorable climbs (first ascents or otherwise)?

Well obviously some of the first ascents at Portland must rank high here. Wallsend Wall, Fond Farewell, Vesuvius and Ammonite's Tooth (both collapsed into the sea now I am told), Sea Saga. Amateur Dramatics and Faceache on Chene Cliff on the east side. Gorgonzola at Lulworth and some of the routes I did with lads from the school on the Little Orme – Genesis, Rapunzel (though that was a repeat of a Boardman route), and the Hornby Crags which we developed on the Great Orme and some of the routes on Cloggy and Gogarth and the Little Orme with Rowland Edwards, who was a much better climber than me and so I was stretched to the limit!

'I retreated with my tail between my legs, as it were, and wondered whether the life of adventure was finished.'

You mention a 'burning ambition' for first ascents in your book. What is it specifically that you enjoy about first ascents and being somewhere that no one has ever been?

Again a difficult one to analyse. The heightened challenge must come into it, though it doesn't only apply to hard rock climbs or mountains. Just to be 'treading somewhere on God's good earth where no-one else has ever been before', as I wrote somewhere, gives an immense satisfaction which it is difficult to describe. And I wouldn't be human if I didn't also admit a certain personal satisfaction, perhaps pride, in achieving it, whatever or wherever it might be.

Tell me a little bit about the boat, the Dodo's Delight. This is actually the second Dodo's Delight.

Right, yes. There was a little accident with the first Dodo's Delight. In 2005, I chose to winter the boat alone in Greenland. It happened in January, when the fjords were all iced over…and, of course, there was a rather amusing aspect that I was skiing across fjords that I'd sailed up a month before, which was rather a romantic notion. I came back to the boat and thought, "Oh, yeah, of course. I must fill the diesel tank for the heater." So I picked up the container and walked along the deck and took out the plug that I'd made above the tank and started to pour the diesel down, and only when I saw red below did I realise that I'd forgotten to put in the vital funnel between the deck head and the tank. I'd been doing this for months so, you know, it was rather a serious senior moment, and the red, of course, was flame. But what surprised me was that I rushed round the side deck, pushed the hatch open, only a matter of seconds, but already smoke was pouring out and I started to go down, and I took one breath and instinctively I thought, "I really mustn't go down there. The fumes seem to be so noxious."

So then I just had this one thought. "I've got to put this fire out." It was ridiculous. I jumped down onto the ice with a bucket and scooped up snow, tried to throw that on into the saloon and onto anything I could find. But, of course, there's not a lot of water in snow as opposed to ice, so it was all hopeless. My surprise was how quickly it got a hold and how quickly things happened, and I remember being up above and still trying to throw anything I could, as it were, onto it. Of course, the cockpit had filled up with snow over the winter and so this was all becoming water, so I was trying to use that as well, but to no avail. The mast, the boom; suddenly that fell in two, so the fire had become that violent by that time. It took me a long time to realise that instead of trying to put this thing out, I should be throwing stuff off the boat. So fortunately I did at last wake up to this and threw the gas tanks that were on the aft seat and threw them onto the ice and anything else I could find.

In the end, it had got such a grip that I actually had to get off the boat and stand and watch it. It was about this time that the local fire service, so called, from Upernavik arrived on their skidoos, and the thing uppermost in their mind was to get me back to Upernavik. I don't know whether they thought I would ask them to put it out or to rescue stuff from it, or whatever it was, but they were dead keen to put me on the back of a skidoo and take me to Upernavik, which they duly did. So I didn't actually see the boat sink through the ice, but I came back on somebody's skidoo the next day and all that was left was one-third of the mast sticking up out of the ice, and a few gas bottles and fenders that I'd managed to throw off. So there I was standing up actually not even in my own clothes, in borrowed clothes, and this was all that I had left in life, as it were, and no credit cards, no passport or anything of this nature. I was completely bereft of anything.

I had fortunately started a Greenland bank account since I was going to stay there the whole winter, so my wife was able to transfer some money there so I could pay for an air fare and go back. The police were very helpful and wrote me a letter explaining why I didn't have a passport in Danish and English. So I retreated with my tail between my legs, as it were, and wondered whether the life of adventure was finished. But fortunately, the insurance did play ball even though it was my mistake, but I suppose that's what you insure yourself against. They did pay out for total loss, which is why I could buy another Dodo's Delight and Dodo's Delight continues and lives again.

Would you say that climbers are natural sailors?

Not necessarily, no. But they do have the great advantage that they're used to danger and challenge and facing things that are not expected, and so yeah, I would say that with the Wild Bunch, because Nico and Ollie - brothers - had done some sailing in the Mediterranean with their parents, but Ben and Sean had done no sailing virtually, and so it was a steep learning curve for them. But I think the fact that they had that basis, that they're used to unknown factors which affect them, and challenge and adventure, it gives them a good start really, yes. The technical know-how just comes by doing it. It's all about challenge. With climbing that is obvious, can I/we do it, especially where it is a first ascent, but even with known climbs if they are a challenge to you. It is the same with sailing. Can we make it, can we fulfil our aim? The fault is probably mine but I can't really see the enjoyment, the purpose, of sailing round the west coast of Scotland, for instance, enjoying the view. There are pleasant anchorages, it's a great cruising area, but what are you achieving – unless it is to teach the grandchildren to sail! Where is the satisfaction?

Would you say that this sort of trip to these wild places is what it's all about for you?

Yes, definitely. I do have difficulty in getting motivated in just sort of sailing around with no particular aim, as it were, just to go to nice places and perhaps to go out for a meal ashore, which is a bit foreign for me. It is much more satisfying, shall I say, if there is an aim, particularly if it's a climbing aim, which has some challenge and adventure associated with it, rather than just sailing around the West Coast because it's a nice place to sail.

It is much more satisfying to do that, because there's challenge involved in getting there in the first place, and a certain amount of technical know-how and sailing the boat, and that adds a considerable dimension to the whole concept. In a way, I'm surprised that not more people have taken this up. You know, Tilman was the guy who pioneered this, but sailing to remote places in order to climb, it's becoming a little more popular and on people's radar, but I'm surprised that more people don't do it, because sailing would - with the ever-decreasing number of places where you can find new routes - add a dimension that could be exploited, in fact.

You have been described as 'The modern Tilman', choosing to make 'Tilman-type' expeditions – what do you make of this? Are you inspired by Tilman?

Yes it was kind of Mick Fowler who was President of the Alpine Club at the time to dub me 'the modern Tilman'. Not least because it means I have two more boats to go before I need retire! No, but it was an honour. It is true we have followed in his wake and footsteps sailing and climbing from the boat in remote regions, sometimes even more directly 'from the boat' than Tilman. I must have got the idea of this type of expedition from reading his fantastic books, and there is no way I could possibly claim to emulate him in his writing, by the way. But with modern equipment and modern climbers we have been able to take the idea a step further and higher.

You are traditional in your approach to both sailing and climbing. Has much changed in the way you think about bolts, marinas, sat nav etc. over the years?

Not really. I was and still am disappointed that they have made Portland a sport climbing area using bolts. We pioneered the routes there in the '60s and '70s trad climbing. Ken Wilson in his inimitable style exhorted me to make a fuss and complain vociferously about it when I got back from sailing round the world, but I didn't see much point. They were going to go on doing it anyway. But I still prefer Pat Littlejohn's take on a visit to Portland, when he was attempting to make a traverse of the whole of the three miles long west cliff and came to a wall with no holds. He aborted, 'perhaps the next generation will be able to do it'. But I can see that sport climbing can be fun and good training for real climbing (i.e. without using aid or bolted protection), as long as it is seen as such. But some seem to see it as an end in itself. One of the things I like about the Wild Bunch is that they aim to free climb their new routes, and train and have fun on sport climbs in France, etc.

Marinas, again no real change there. They are expensive for a start. Of course they are convenient, you can step off onto a pontoon without the hassle of getting ashore in your dinghy, but haven't we made the whole thing too easy nowadays? My first visit to the Azores was in 1984. No marinas, maybe a quayside in the two main harbours of Horta and Ponta Delgado but otherwise you put your own anchor down. My last return there in 2008, marinas in every harbour. To me it spoilt the pristine simplicity of it, the remoteness and the sense of achievement. But of course there are many more people and boats sailing nowadays and you have to put them somewhere!

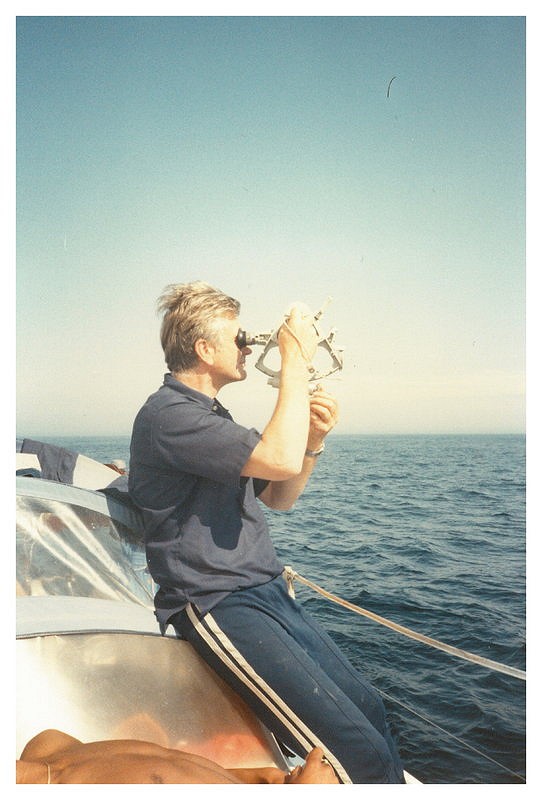

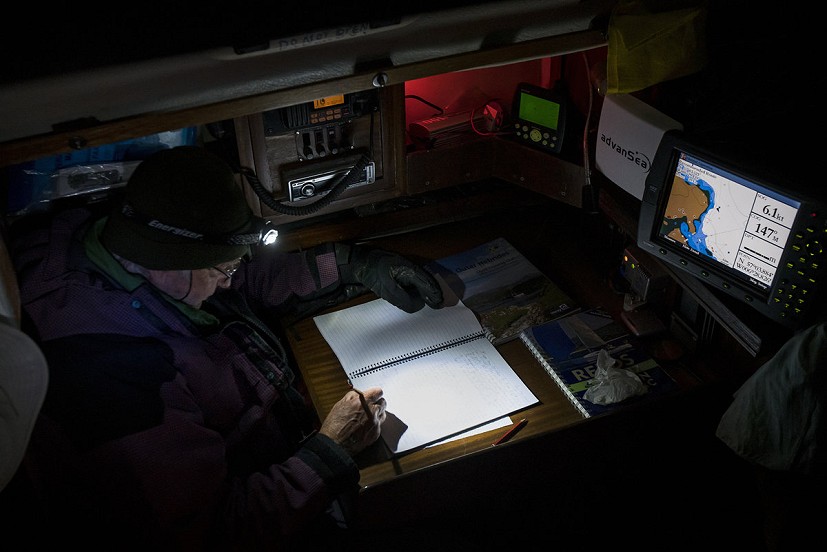

Sat nav, or at least GPS. Well, I don't think I was ever against those. Of course my first ocean passages were by astro-navigation but when sat nav and then GPS came along I seized them with both hands. My maths was always so weak and it was such a labour working out your position from the sun or whatever! But I did have a hesitation about it and still do: people put a GPS on board and know their position accurately so go off ocean sailing without serving their apprenticeship and building up a bank of experience first.

'Addicted to Adventure' – are you really?

I think I must be really, though I am slowing down in my old age! But life is awfully boring without any challenge…though there are challenges that are not physical but we won't go into all that.

How do you keep so fit and nimble at 82?

I used to say, by making sure I keep putting condensed milk into my coffee! But with the down on sugar nowadays I have stopped doing that. But I have been incredibly lucky (I prefer to say God has looked after me wonderfully and I am very grateful). I have so far never broken anything and I do seem to keep healthy and well naturally.

Tell us a bit more about your next challenge...

Yes, that's not to say that my next project, repeating Shackleton's traverse across South Georgia on skis, is not forcing me at my tender age to undertake a protracted course of training with work-outs and walking the hills! I aim to sail from the Falklands in Novara, a 60ft ketch with an aero-foil rig, to South Georgia and to repeat Shackleton's traverse across on ski. Can an old man of 82 do it? There's the challenge, and getting back again to the Falklands against the wind in the Drake Passage!

Watch the musical trailer for Adventures of the Dodo's Delight below:

Comments