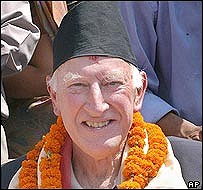

So naturally did he fit this role of elder statesman – Band served as president of both the Alpine Club and the BMC – that it was easy to forget that in 1955 the smiling, white-haired gent regaling you in a lecture hall or club bar had made the first ascent of Kangchenjunga, with Joe Brown, and two years earlier had helped forge the route through the Khumbu icefall that Hillary and Tenzing would follow to the summit of Everest.

Kangchenjunga and Everest confirmed Band as one of the top alpinists of his day. However he remained an amateur – in the best French sense of the world – climbing for the love of it, while making his career in the oil industry.

George Christopher Band was born in 1929 in Japanese controlled Taiwan where his parents were Presbyterian missionaries. He was educated at Eltham College, south London, and Queen's College, Cambridge, where he studied geology and became one of a mainly Oxbridge set pushing the standard of British climbing in the Alps. When John Hunt chose his team for Everest, he included not only Band who had been president of the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club but a recent president of its Oxford equivalent, Michael Westmacott, though neither had climbed in the Himalaya. It was that class of expedition, and at age 23 Band was the youngest of the climbing team.

Band had other qualifications that appealed to Hunt besides a 1952 season in the Alps which included a string of first British or first British guideless ascents. National Service in the Royal Corps of Signals appeared to make Band a natural for radio duties and when he pointed out he had actually been a messing officer, Hunt responded, "Better still, then you can also help... with the food."

Band spent a week in the hazardous Khumbu icefall, along with a small group of other climbers, weaving between ice walls and bridging crevasses, opening the way into the Western Cwm, the great glacier trench that leads to the south side of Everest. Names given by the climbers to features in the icefall – such as Hillary's Horror and the Atom Bomb Area – give a taste of the unstable terrain.

A bout of flu obliged Band to descend to the valley to recuperate, but he returned to help ferry loads up the Cwm and on to the Lhotse Face, as well as performing his radio duties, monitoring weather reports, and dishing out rations. His high point was escorting a group of Sherpas to Camp VII at 7,300m.

On 2 June, three days after Hillary and Tenzing had, in the Kiwi's immortal words, "knocked the bastard off", Band tuned in the radio to the Overseas Service and the team listened to the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Then came an additional announcement: "Crowds waiting in the Mall also heard that that Mount Everest had been climbed by the British Expedition." The climbers were dumbfounded that the news had got back so soon – a scoop for James (now Jan) Morris of The Times who accompanied the expedition. Band recorded in his diary: "A lively evening. Finished off the rum. Sick as a dog!"

Back home, the Everesters were feted as heroes; Band returned to Cambridge for his final year and five days after his last practical examination was at London airport bound for Pakistan and an attempt on 7,788m Rakaposhi in the Karakoram. The CUMC team, led by Alfred Tissières reached a feature called the Monk's Head 6,340m on the southwest spur before being thwarted by days of fresh snow. Band told the story in cheery style in Road to Rakaposhi (1955). As remarkable as the climbing was the team's decision to drive a Bedford Dormobile the 7,000 miles from Cambridge to Rawalpindi and back, via Damascus, Baghdad and Teheran. Three climbers drove it out, and the other three, including Band, drove it back. He hoped the journey through 10 countries would be sufficient to learn how to drive, but failed his test twice on return.

Band wrote the preface to Road to Rakaposhi while on the 1955 Kangchenjunga expedition. Led by Charles Evans, a Liverpool surgeon, it was a very different affair to Everest: compact and low key with much less national pride at stake. In fact as the climbers would be exploring new and dangerous ground there was no expectation they would reach the top; the expedition was a "reconnaissance in force". It was also a more socially mixed team than on Everest, exemplified by the pairing of Band with Joe Brown, a jobbing builder from Manchester just making his name as a rock-climbing phenomenon.

Band was on messing duties again. He recalled being popular at first, but there were few villages en route and the craving for meat, eggs and fresh vegetables became strong. "I was constantly reminded that 'Just in case you're getting swollen headed, Band, the grub's bloody awful.'"

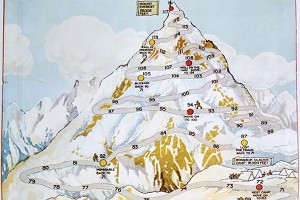

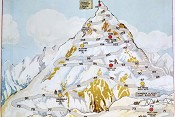

Ascent of the 8,586m peak, third highest in the world, would be via the southwest face. Nobody had been higher than 6,400m on this side of Kangch' and John Hunt predicted, correctly, that the technical climbing problems and objective dangers would be of a higher order than on Everest. The team endured screaming winds and blizzards, but eventually Band and Brown pitched their tent on an inadequate ledge at 8,200m. Next day, 25 May, dawned fine – "the God of Kangchenjunga was kind to us," wrote Band – and after a couple of pints of tea and a biscuit the pair set off for the summit. Shortly before the top they came to wall broken by a vertical cracks – an irresistible temptation to Brown. Cranking up the flow on his oxygen bottle, he disposed of the highest rock pitch ever attempted, though it would have been a modest Very Difficult grade a sea level; Band followed, and there, 6m away and 1.5m higher, was the summit snow cone. They respectfully left it untrammelled.

The following day two other climbers, Norman Hardie and Tony Streather, also reached the same point. On return to Base Camp the climbers learnt that one of the Sherpas, Pemi Dorje, had died of cerebral thrombosis. To the Sherpas, it seemed, the God of Kangchenjunga had demanded a sacrifice after all.

Lecturing and writing kept Band independent until 1957 when he pleased his parents by getting "a proper job", beginning a long career with Shell, initially as a petroleum engineer then moving up the executive ladder. Oil and gas development took him to seven different countries – some, like Venezuela offering climbs on the side – before returning to England where, in 1983, he was appointed director general of the UK Offshore Operators Association.

When the Alpine Club celebrated it's 150th anniversary in Zermatt in 2007, George was in his element. For the media, AC leaders and their mountain celebrity guests made a mass ascent of the Breithorn, the 4,164m snow summit above the resort. George had climbed it in 1963 during the club's centenary celebrations, via the tricky Younggrat. Fifty years later he reached the summit again, albeit by the easier standard route, but at aged 78 a testimony to an unquenchable enthusiasm for the mountains.

George Band seemed to defy the years. Such was his stalwart presence that word that George was suffering from an aggressive prostate cancer came as a shocking surprise. He isn't the last of his generation, members of the Everest 1953, Rakaposhi and Kangchenjunga expeditions live on, but he was the most publicly active. Though Hunt, Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were gone, George tirelessly kept the Everest show on the road at reunions, festivals, lectures and charity events. It was in a way a family affair and he took on the fatherly role with conscientious grace and genuine enthusiasm.

- Many UKC Users have already paid their respects to George on this UKC Forum Thread.

Stephen Goodwin is the editor of the Alpine Journal. He is a an accomplished climber and writer and was one of the founding journalists of The Independent.

He lives near the Lake District where he enjoys rare dry days on the crag and more usual damp days on his mountain bike.

- PHOTOS/REVIEW: The Alps - A Bird's Eye View 9 Jun, 2010

- OBITUARY: Toma? Humar 17 Nov, 2009

- Obituary: Charles S. Houston 4 Oct, 2009

Comments