Body shape is a weighty topic in climbing, but one that deserves more open discussion - especially with regard to young female climbers, argues Natalie Berry.

A recent article in the New York Times handled the topic of transition from junior to senior level in sport, using the success of up-and-coming US distance running star Katelyn Tuohy to frame the discussion. 'America's Next Great Running Hope, and One of the Cruelest Twists in Youth Sports' reads the headline. The 'cruel twist' turns out to be puberty; the normal physical and biological changes that go with it and the role they can play in a young female athlete's performance and career.

Puberty can be cruel, there's little doubt about it. Spots, squeaky voices and hormonal changes are the source of all kinds of temporary embarrassment and diminished self-esteem. The side-effect of puberty that the author describes as cruel, however, is the weight gain and change in body composition that occurs in healthy female development and their typically detrimental effects on pubescent and adolescent girls' running times.

'They are nothing but skin and bones and lungs in their early years,' a professor of health sciences comments in the article. 'They' - referring to the young female runners – struggle to acquire the additional strength required to carry along their increased body weight, the article explains. 'Why do so many gifted teenage female distance runners fizzle out by their early 20s, unable to capture the speed of their youth?' the author asks, later describing this conundrum as a 'cruel puzzle' in the text.

It's difficult to disagree with the hard facts outlined in the piece, but the narrative is nonetheless potentially harmful in its framing of the journey into womanhood as an inconvenient hurdle to overcome. Rather than focusing on a sporting career tailored toward longevity and fulfilment, the notion that healthy physiological development is a career-threatening nuisance is not conducive to fostering a healthy attitude toward sport in young girls and women.

This article IS the problem. Not puberty. Not girls having their own NORMAL development curve that differs from boys. Stop punishing women for having normal woman experiences and making them dread womanhood. Ultimate potential is found in a woman's body. https://t.co/2OoPgHW2nm

— Lauren Fleshman (@laurenfleshman) June 9, 2018

An article in Outside Magazine pulled together these criticisms from the running world, while also drawing attention to the fact that female track and field world records are held by women and not young girls. 'No running career is a linear progression towards success,' Martin Fritz Huber writes, before citing examples of late bloomers, premature burn-outs and great come-backs.

The same maxim can apply to climbing, or to many other sports, for that matter. It's important to acknowledge the role that physiological variation plays – there's no one-size-fits-all hypothesis to be made when it comes to human growth and physical development. And when it comes to success, there are always outliers.

The parallels between the running and climbing worlds on the issues surrounding weight gain are obvious, and the effects on climbing performance perhaps even more significant. The very premise of our sport hinges on that old cliché of defying gravity. You don't need a degree in physics to understand that the greater your mass, the greater your weight and the harder it is to haul yourself up a climb – bluntly put. Body weight is an unfortunate, but patently evident and inevitable determining factor in climbing performance – to a certain extent, in a sport with many variables, of course. It's at once a source of fat-shaming 'banter' between friends, and a very heavy elephant in the room for a quick fix if you're wondering how to improve.

Unfortunately, for some people – and young athletes in particular – their weight becomes an unhealthy obsession and the elephant in the room their reflection in the mirror. For vulnerable athletes, once a perceived connection between weight and performance is established, it can develop into a serious illness. Recognising an unhealthy trend among competition climbers, in 2016 the International Federation of Sport Climbing introduced mandatory BMI checks with a minimum index of 17 for semi-finalists at senior World Cups.

While adolescent males have the potential to exploit increased muscle mass and enhanced performance [1], mother nature dictates that females gain less metabolically advantageous tissue in the form of fat and in turn 'fill-out', a phrase that's rarely music to the ears for any young girl and for an athlete, likely rarer still. Although it's generally understood that increased body fat reduces mechanical efficiency in weight-bearing sport in adult women, the metabolic consequences of this increase in adolescent females as the body changes during puberty are yet to be thoroughly investigated.[1]

In his training book Make or Break, Dave MacLeod outlines the path often taken by young climbers who've experienced an exponential curve in performance before hitting a wall, so to speak. 'During adolescent growth, there is increased risk of climbers adopting unhealthy eating patterns in order to reduce their weight,' he writes. 'Bone mass doubles during the years 13-17, which may explain some of the remarkable climbing performances achieved by children who are very much lighter than their adult counterparts. […] During this period, attempting to offset body mass increases by reducing body fat percentage is unlikely to be performance positive, since it interferes with growth and reduces the capacity to maintain training.' It's no secret that elite level gymnastics has long been predicated on – and tainted by - reducing body fat and stunting growth to improve performance.

For young girls and women, the effects of this difficult period can be especially harmful to health and wellbeing in the long term. The 'Female Athlete Triad' - disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis – is a studied trio of illnesses associated with female sports participation and widely recognised by sports coaches and doctors. Stating the obvious, perhaps, a study reveals that when it comes to eating disorders, 'sports that emphasize low body weight can be a risk factor.' [2] Unfortunately, there remains a culture of silence, shame and taboo surrounding these issues that needs to be broken by climbing coaches, parents and athletes alike.

If the prospect of hindered performance isn't enough to trigger insecurity, then negative body image might just be enough to tip the scales – especially for young women and girls, and for those in the media spotlight even more so. American professional climber Sasha DiGiulian has spoken openly about her struggles with body image. 'When I was 18 and won the World Championships, I remember reading posts about me in online forums speculating that I was anorexic and attributing my success in climbing to my light weight,' she wrote in an article for Outside Magazine. 'My perception of myself changed then. I started paying much more attention to my diet, how to maintain a youthful body frame, and became convinced that in order to climb hard, I needed to stay at a certain weight. This meant strictly watching my caloric intake and exercising excessively or feeling guilty, for instance, after indulging.'

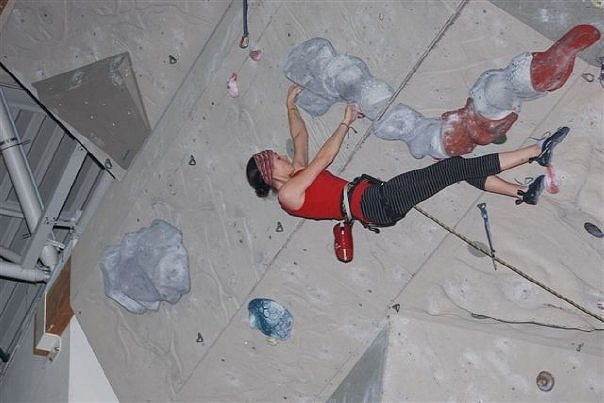

However, biology eventually caught up with DiGiulian and she began to gain weight. 'I no longer had the body of a prepubescent girl. With these changes came a new challenge: self-acceptance,' she explained. 'As our female bodies mature in climbing, we need to replace litheness with strength. So I began lifting weights. As a result, my body changed again.' DiGiulian's experience is common and recognised in more mainstream sports. According to one study [1], additional fat gain 'may have the potential to 'socialise' [girls] away from sporting aspirations,' which 'may be particularly evident in the weight-bearing aesthetic events such as gymnastics, diving and figure skating.' In these sports – much like climbing – a lean physique is often inextricably tied to success as an athlete.

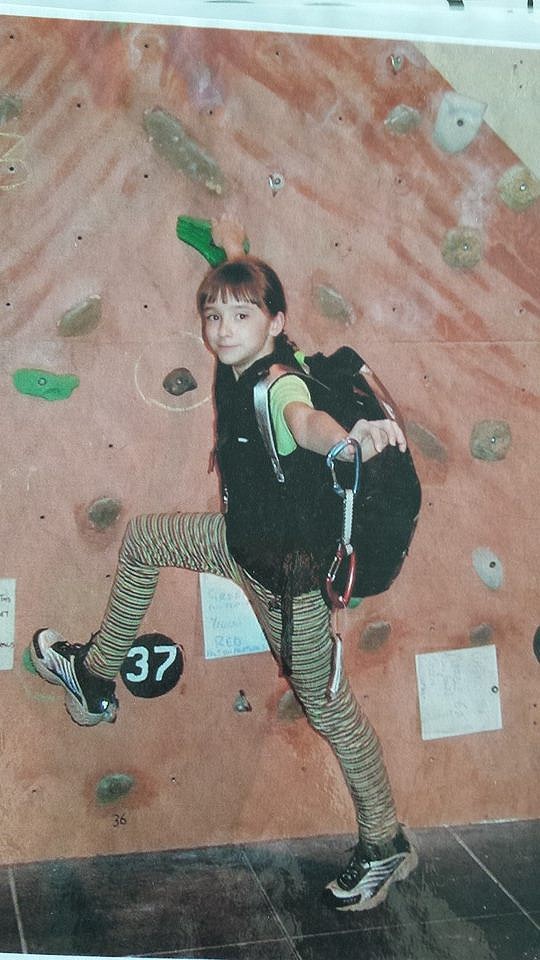

Having made the bumpy journey as a junior competition climber myself, I know how it feels to suddenly be lumbered with a body that seems alien and wholly unsuited to your chosen sport. As a kid, adults would put my ability down to my low weight – some even tried to guess it. 'You can't weigh 6 stone soaking wet!' Later, comments were made along the 'My how you've grown!' lines. 'You're really filling-out!' Groan.

'Hips won't help me climb 8a!'; 'Bigger thighs will weigh me down!'; 'Breasts just push you further away from the wall!' I felt like Gregor Samsa in Kafka's Metamorphosis, and far from his sister Grete, who eventually 'blossoms' into a woman. Floral imagery – often associated with the female body – didn't seem to accord with the strength and mental robustness that climbing required of me. Coming of age in a predominantly male sporting environment over 15 years ago, without any female role models to assure me that it was just a bump in the road, a crux on the route to womanhood, was tough. I vividly recall when I was around 11, a strong adult female climber lamenting her childhood, but regretting puberty. "Oh god, I'd never want to go through puberty again!" she laughed. I gulped.

Later on, I remember my GB teammates discussing reasons for the drop in numbers and standard in the Female Junior category (age 17/18). One of the boys paused thoughtfully, and posited "I dunno. I think they all get, like, pregnant and stuff." We burst into laughter, but he wasn't all that far off the mark. If pregnancy wasn't the issue, the girls' bodies were damn well preparing for it - broody or not. As females, our physiques seemed to be compared and contrasted more than the boys' bodies ever were. 'She makes you look obese, Nat!' was a memorable comment delivered by a grown adult.

A late developer, I plateaued around age 17 and continued to struggle with my new body in my early 20s. Although I was – and still am – an archetypal echtomorph (long, lanky limbs), I gained weight nonetheless, some of which lingered until my early 20s. The step up to senior level was difficult, and not only in terms of the route grades. I was weighed down mentally by the burdening belief that I wasn't the same climber I was as a kid. I didn't realise the hard truth that I never could be the same climber, but that equally I could become even better – it would just take time and effort. I had won a European Youth Cup round and people spoke of 'great potential' and 'talent.' They didn't talk as much about adapting to a body that seemed to me to be more geared-up for parenthood than podiums. I didn't see it as just a blip in a long career of climbing, and my younger, naïve self accepted it as a demoralising finality.

Like Sasha, I put my lithe physique on a pedestal and strove to uphold it as my level plateaued. My self-perception was likely compounded by repeated well-meaning but nonetheless nuanced comments throughout my youth that I possessed 'the perfect build' for a climber. I played with my food and became fixated on aerobic exercise – fortunately, though, for whatever reason I never took it to a dangerous extreme, although I opened myself up to multiple injuries through inappropriate training and nutrition.

'Maybe I'm just not cut out for this?' I thought. Now at the ripe old age of 26, wisdom has taught me that very few people are so definitively 'cut-out' for anything. Our shape and form are not foreordained by some deterministic biscuit cutter, rather we're rolled-out, hand sculpted and remodelled numerous times through growth, weight fluctuation, illness and injury. There's no such thing as 'a perfect build' for climbing. Before commenting on a young person's growth, we should consider if it's appropriate or necessary – no matter how good our intentions, some comments cut deeper and linger longer than we'd expect.

Although training gains do occur in young athletes, strength and endurance develop best from the late teens onwards, when the body's hormonal state has developed to allow training to stimulate muscle growth, MacLeod writes in Make or Break. Meanwhile, technique is developed faster during this period than any other time in life. 'The best thing adolescent climbers can do to optimize their progress is to continue to focus on their climbing technique and tactics,' he suggests. As one of the strongest components of long term success in the sport, he argues, a focus on technique gives young climbers 'the opportunity to gain an advantage over others who may resort to short term tactics of weight control or dangerous strength training practices.' Diet and nutrition in sports performance is an ever-evolving field of study, and MacLeod suggests that current research points to high quality protein as vital for supporting growth in young athletes. 'A key concept for youth climbers to understand is that building muscle absolutely requires amino acids, varied nutrients and energy,' he tells me.

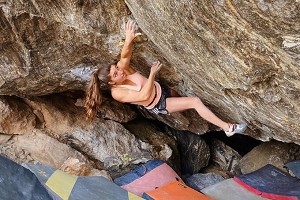

Climbing itself comes in many forms, and its participants in many shapes and sizes – even at elite level. The reason for the diversity in climbing somatotypes likely stems from the number of performance variables. Weight is just one element alongside height, strength, power, endurance, flexibility, efficiency of movement, technique, footwork, dynamic/static strength, core stability, route-reading skills and perhaps the most crucial yet often overlooked asset: mental strength.

Even if your power to weight ratio is optimal, you'll get nowhere if your head's not in the game on the crux of your project. If you can't route-read and find the crucial rests, you can be light as you like and your heavier, savvier, less 'fit' mate might just outdo you. If you're overtraining and not eating sufficiently, getting out of bed might prove to be the crux of the day. 'Real rock offers much more variability in how a move can be done, and tends to flatten out advantages or disadvantages of different body shapes,' writes MacLeod. 'Those who take part in a variety of climbing disciplines and climb outside may be less likely to feel pressure to adopt short term thinking which increases the risk of injury,' he suggests.

Physical maturation can bring greater strength, technique and...wisdom? It's not all about the endless endurance you have as a youth. Cries of 'Kids don't get pumped!'; 'But she has smaller fingers!' are well and good, but there comes a point in sport when a new body develops, potentially bringing more than just clumsiness and attention from the opposite sex: a dip in performance and with it a loss of bodily confidence and motivation. Young climbers – females in particular – must be warned that the achievements enabled by their childhood physique in no way determine their athletic success post-puberty. Being realistic that their power to weight ratio likely won't always be to their advantage is key. Equally, though, just like the many variables involved in climbing, life itself will throw factors into the mix, which will likely have a greater influence on sporting success than physical changes ever could: school/university studies, social commitments, new hobbies and interests – the list goes on.

As the Chinese proverb goes, 'The flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long.' Sometimes, though, young athletes self-extinguish their ambition before it's had the chance to burn brightly. Whether it's to avoid burn-out and illness or simply encourage a demoralised adolescent, as we sprint towards the Olympics in Tokyo 2020, it's vital that parents and coaches ensure that young climbers are geared up for the long-distance race, too: a healthy and happy future in climbing, no matter what hurdles they have to negotiate along the way.

1. 'Physiological Issues Surrounding the Performance of Adolescent Athletes' - Geraldine Naughton, Nathalie J. Farpour-Lambert, John Carlson, Michelle Bradney and Emmanual Van Praagh, Sports Med 2000, Nov; 30 (5), pp. 309-325

2. "The Female Athlete Triad: Disordered Eating, Amenorrhea, and Osteoporosis," Rust, DawnElla M., The Clearing House, vol. 75, no. 6, 2002, pp. 301–305

- SKILLS: Top Tips for Learning to Sport Climb Outdoors 22 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

Comments

I went through puberty as a competitive gymnast and a lot of this sounds horribly familiar. I also remember hitting a plateau, losing confidence in my body image and under-eating in an attempt to compensate. Some of the things that worried me weren't even related to pubescent changes, just growth. I remember being very anxious because I grew tall enough that I couldn't do giants on the bars without piking any more. It took what felt like forever to get the timing of the pike right and in that time I couldn't get through a routine clean because I kept kicking the other bar and coming off. I thought that was the end of my career and I was devastated - I was 12. And I remember watching other girls hitting puberty plateaus and dreading the changes I knew my body was going to go through.

In the end, I stopped competing at 18, part way through my late puberty. I couldn't take the way we were all constantly watching our own bodies and each other's any more. It wasn't a healthy place to be a teenager.

Of course, anxiety around puberty is part and parcel of any normal adolescence too but I think the issues described are of particular importance in the world of competitive sport.

Thanks for a very resonant article!

Great article. Well written and put together. Thanks for writing and sharing.

Good piece. I was remarking to an instructor at my local wall that it must be hard for young female climbers when they hit puberty and he said that one of the things that hit them unexpectedly (along with the increase in weight/drop in PTW ratio) is that their growth in height/longer limbs mess with their previous sense of where their bodies `finish' and their sense of spatial awareness. Something I hadn't considered. The issues are obviously more problematic with young girls and body image etc, but I was interested to read Tommy Caldwell write (in `The Push') of how hard/inexplicable he found it when he hit puberty and suddenly experienced a drop in his performance, due to increase in weight, and how it took him several years to realise how to adapt to become a better climber than before.

Great, thought-provoking article! Thanks.

Yes, this sounds familiar too. The weirdest thing for me though wasn't so much around height/limb length, but a shift in the location of my centre of mass that meant I felt like I had to learn a lot of the basics again.