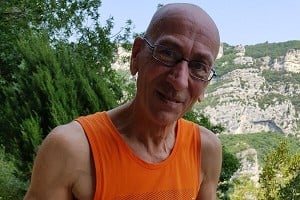

Simon Richardson - editor of scottishwinter.com - reflects on the highpoints of Hamish MacInnes' long and varied life, following his death aged 90 in November.

Hamish MacInnes (1930 – 2020)

As a schoolboy I grew up on a diet of climbing books borrowed from the local library. I read and reread Chris Bonington's I Chose to Climb and Tom Patey's One Man's Mountains – captivated by their tales of adventure and excitement both at home and abroad. There is an underlying sub plot to both these books, namely Scotsman Hamish MacInnes, who acted as mentor to Bonington and friend and rival to Patey. Energetic, creative, adventurous and highly unorthodox, MacInnes did not just help shape these two great climbers, but made a significant impact on the entire British mountaineering scene through the 1960s and 70s. His influence continues to this day.

Hamish MacInnes was born on 7 July 1930 in Gatehouse of Fleet in Galloway. He enjoyed a happy childhood, exploring the local countryside and spending time with local gamekeepers. At the age of 14 the family moved to Greenock, west of Glasgow, where he befriended his next-door neighbour, Bill Hargreaves, who worked as a tax inspector. Hamish was intrigued as to where Bill disappeared to every weekend on his motorcycle, with a rope on his back, so Hargreaves introduced him to the Cobbler. Hamish took to climbing like a duck to water and later teamed up with Charlie Vigano (the only person ever to be a member of both the Creag Dhu and Rock and Ice Clubs). From the outset Hamish had big ambitions. When he was 18 years old, he hitchhiked across war-torn Europe to Switzerland intent on climbing the Matterhorn. Unable to afford hut fees, he made a solo ascent of the Hornli Ridge, up and down from Zermatt in a day. Hamish then spent 18 months in the Austrian Tirol on National Service, which gave him many opportunities to develop his technical skills in the Eastern Alps.

On his return to Scotland in 1950, Hamish fell in with members of the Creag Dhu and focused on climbing in Arrochar and Glen Coe. On the Cobbler he made several noteworthy first ascents with Bill Smith including Gladiator's Groove (E1) and Whither Whether (still considered to be one of the best mountain VS pitches in Scotland). In June 1951 he opened his Glen Coe account with the first ascent of an old-fashioned gully with John Cunningham – Dalness Chasm Left (VS) – and three months later succeeded on a far more futuristic climb – Engineer's Crack (E1) with Vigano and Bob Hope. Eyebrows were raised by their creative tactics. "There was Hamish on Engineer's Crack, penduluming in off Fracture Route with his loud war whoops," Jimmy Marshall recounted many years later. "That upset a lot of people."

But MacInnes was undeterred, and a series of fine new Glen Coe routes flowed in 1952 including Wappenshaw Wall (VS) and Peasant's Passage (HVS) and a winter ascent of Clachaig Gully (originally graded IV but now considered to be at least V,5). MacInnes' vision blossomed in February 1953 during a remarkable week of climbing with 18-year old Chris Bonington that saw off three long-standing winter problems on Buachaille Etive Mor. They kicked off with the first winter ascent of Agag's Groove (VII,6) in the company of John Hammond and Gordon McIntosh (MacInnes led one pitch in socks), and then on consecutive days made first winter ascents of Raven's Gully (V,6) and Crowberry Ridge Direct (VII,7). These routes catapulted Glen Coe ahead of Tom Patey's developments in the Cairngorms such as Scorpion (V,6) and Mitre Ridge (V,6). The modern Grade VII ratings are impressive, but this was before front pointing, and ice climbing techniques were still rudimentary. Raven's Gully was probably the most demanding of the three, and arguably the most difficult winter route in Scotland at the time.

1953 was a big year for Hamish. After attending a lecture by Andre Roche about the Swiss attempt on Everest the previous year, he realised that the expedition had left a series of food dumps all the way up to the South Col. Hamish's fertile mind thought this was too good an opportunity to miss, so he conceived the Creag Dhu Everest Expedition that would make use of the in-place supplies. (The name was a misnomer, because MacInnes was never an official member of the Creag Dhu). John Cunningham, along with several other members of the Creag Dhu, had recently emigrated to New Zealand, so Hamish travelled there by boat where Cunningham was astonished to find the expedition was to comprise just the two of them. By the time they arrived in Nepal, Hunt's expedition had already succeeded on Everest (and taken full advantage of the Swiss food dumps), but undeterred they continued to Everest Base Camp carrying 30kg rucksacks and living on a diet of potatoes. They made an attempt on Pumori, but beaten back by avalanches they finally succeeded in making the first ascent of Pingero, a prominent sub-peak of Taweche.

Hamish climbed in New Zealand over the next few seasons where he made a number of first ascents including the very fine Bowie Ridge (IV) on Mount Cook and the South-West Ridge (IV) of Nazomi above the Hooker Glacier. This was described by a New Zealand commentator at the time as "possibly the most difficult rock climbing ever achieved in this country."

Back in Scotland, MacInnes turned to one of the greatest prizes of all – the first winter ascent of Zero Gully on Ben Nevis. Competition was intense and MacInnes tried it six times before he was successful in February 1957 with Tom Patey and Graeme Nicol. The Creag Dhu were disappointed that Hamish did not keep it within the club but "as Hamish pointed out, the gully was virtually his property; since most of his property was in the gully we could but agree," Patey explained afterwards. The lower 100m of the gully is a vertical corner choked with ice overhangs. MacInnes and Patey shared leads, with Patey using tension from ice pitons and MacInnes front pointing between ice pegs. Zero Gully was a huge psychological breakthrough and the forerunner to the great Nevis ice routes culminating in Orion Direct climbed by Marshall and Smith three years later.

In summer, MacInnes formed a strong partnership with Ian Clough and on Skye they made first ascents of Vulcan Wall (HVS), Creag Dhu Grooves (E3) and Strappado (HVS). MacInnes renewed his partnership with Chris Bonington in 1957 and introduced him to the Alps. They failed on their first route (an attempt on the 1938 Route on the Eiger) but later in the trip climbed a new route on the Aiguille du Tacul.

A year later they made an early repeat of the Bonatti Pillar on the Dru with Don Whillans and Paul Ross. Hamish was hit by a rock that fractured his skull on the first day, but he persevered for three more days to record the first British ascent. The following summer he climbed the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses with Whillans, John Streetly and Les Brown. They thought this was going to be another first British ascent but began to have doubts when they found an abandoned Smarties tube high on the route. They discovered on the descent that they had been beaten to the prize by Robin Smith and Gunn Clark by a few hours.

Two years later in 1961, MacInnes visited the Caucasus with George Ritchie and made a gruelling 13-day storm-bound traverse of the Shkhelda massif. Rather optimistically they had only packed food for four days but were kept alive by a Russian tradition of burying emergency supplies on key summits.

In Glen Coe more significant new routes followed in the 1960s including Crypt Route (V,6) and Pterodactyl (V,7). The big prize however was the first winter traverse of the Cuillin Ridge on Skye with Patey, Davie Crabb and Brian Robertson in 1965. Similar to Zero Gully, the Cuillin Ridge had assumed 'last great problem' status and had been attempted over a dozen times, including six by MacInnes. Their success, over three days in February, was a testament to MacInnes' determination and opportunism to drop everything and go for the route, when conditions were just right.

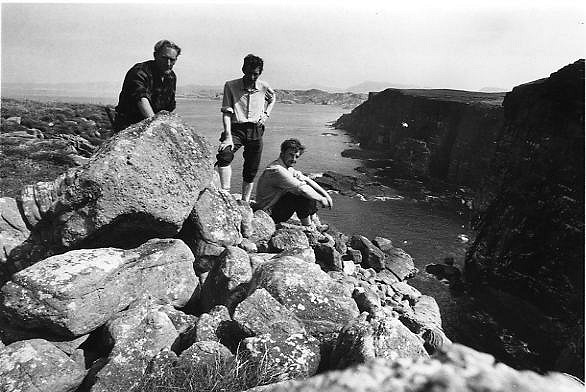

1969 was a prolific climbing year for the 'Fox of Glencoe' with first ascents of The Wabe (V,5), Innuendo (V,6), Sabre Tooth (IV,5) and West Chimney (V,6) in Glen Coe and Route Major (IV,4) on Ben Nevis. In summer he climbed the impressive Jib (E1) on Blaven on Skye, and made the first ascent of The Great Stack of Handa (VS), one of Scotland's largest sea stacks, with Graeme Hunter and Doug Lang. In the North-West, MacInnes took a strong interest in Fuar Tholl, recording several new routes on the South-East Cliff such as Boat Tundra (VS) followed by Sleuth (VS) on the imposing Mainreachan Buttress. MacInnes returned to Sleuth a few months later and made a winter ascent with Kenny Spence and Allen Fyffe. Graded VII,7 and still rarely climbed today, this sustained turfy mixed route was probably the most difficult winter route in Scotland at the time. Once again, MacInnes was at the cutting edge of winter development.

By the mid 1960s, routes such as Point Five and Zero were being climbed in fast times. This was due to the development of crampons and front point technique. This eliminated the need to cut footholds, but much time was still spent cutting handholds. MacInnes was an exponent of front pointing with the aid of two axes, relying on driving in straight picks for balance, but this proved dangerous as they readily pulled out. Cunningham experimented with ice daggers that could be driven into the ice above the head allowing the climber to move up very quickly for a couple of moves. This was a stressful and strenuous technique that was too precarious for sustained climbing at high angles.

The technological advance came later that 1970 season when Yvon Chouinard visited from the USA. Chouinard had been experimenting with a curved pick tool, to allow fast movement across long ice slopes in the High Sierra. He showed his tools to Cunningham at Glenmore Lodge and then MacInnes in Glen Coe. MacInnes had a strong engineering background (he built a car from scratch at the age of 17) and had developed 'The Message', the first all-metal ice axe in the mid 1950s. He had also been experimenting with new axe designs with limited success, but after talking to Chouinard he increased the angle of his pick and came up with the Terrordactyl – the first of the dropped pick tools.

The following winter, MacInnes showed their effectiveness by making the first winter ascent of Astronomy (VI,5) on the Ben with Spence and Fyffe. It was a typical unconventional MacInnes affair involving a bivouac and seconds following on jumars, but it demonstrated the effectiveness of the new ice tools on steep, thinly iced ground. Terrordactyls went into production later in 1971 and the 'curved axe revolution' was underway.

Within a couple of seasons ice climbing grades rocketed, and to this day, the Nevis thin face routes climbed in the early 1970s remain the most sought-after winter routes in Scotland. Back in Glen Coe Hamish made the first ascent of Evening Citizen (V,7) in Stob Coire nan Lochan and made a winter ascent of Route I on Rannoch Wall. Evening Citizen was not repeated until 1995 and Route 1 is almost certainly undergraded at V,6. Both routes made full use of the new ice tools and pointed towards the significant rise in mixed climbing standards that were to take place in the 1980s and beyond. These advances were fuelled by the introduction of reverse curve banana picks – such as the Simond Chacal – which were a natural evolution from Hamish's dropped pick Terrordactyl design.

During the 1970s, Hamish's focus was directed further afield. In 1970 he made a second visit to the Caucasus, coming away with the first ascent of the difficult North Face of Pic Shchurovsky with Paul Nunn and Chris Woodall. In 1972 he took part in the first expedition to attempt the South-West Face of Everest, and in 1973 he climbed the Great Prow on Roriama in Guyana with Joe Brown, Mo Anthoine and Don Whillans. He returned to Everest in 1975 as deputy leader of Chris Bonington's successful South-West Face Expedition. Hamish was responsible for the tents, and working from an idea initiated by Don Whillans in Patagonia, he designed 'MacInnes Boxes'. Rectangular in shape they had adjustable front legs which allowed them to be pitched on any angle of slope. They also had a fabric cowl which deflected avalanches. Typically, Hamish was the only person who knew how to erect them, but they were critical in allowing the team to move up and down the relentlessly steep South-West Face. Ultimately, Doug Scott and Dougal Haston completed the route becoming the first Britons to climb Everest.

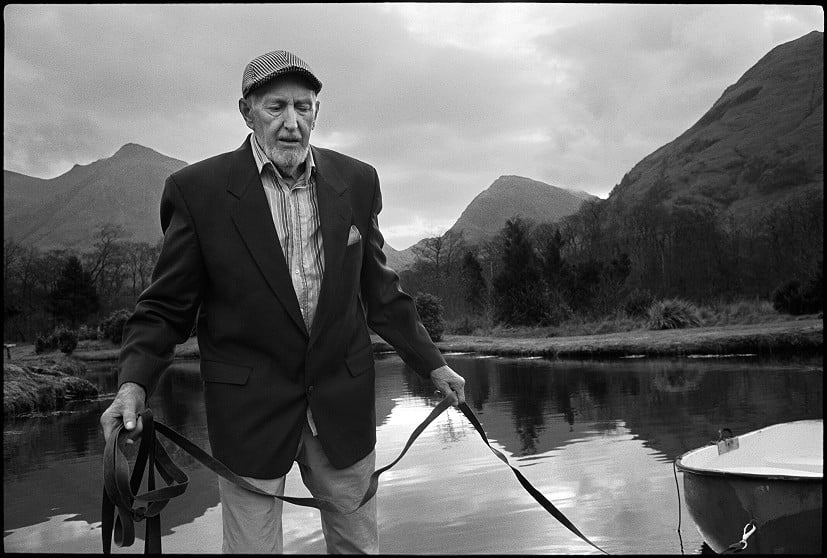

Back in Scotland, Hamish's new route days were largely behind him and his last recorded first ascent was Dalness Chasm Right-Hand (IV) on the Buachaille in 1979. But his focus had moved on to other things. From the mid 1960s to mid 1970s he ran the Glencoe School of Winter Mountaineering that attracted some of the best climbers of the day as instructors including Allen Fyffe, Kenny Spence, Jim Macartney, Ian Nicholson, John Hardy, Wull Thomson, John Grieve and Ian Clough. In 1961 he founded the Glen Coe Mountain Rescue Team. As leader of the busiest mountain rescue team in the country for 30 years, Hamish was involved in hundreds of rescues and saved countless lives. His engineering prowess led to the invention of the MacInnes Stretcher, a lightweight foldable design that allows it to be carried as a rucksack to the scene of the accident. These stretchers are used by many rescue teams around the world.

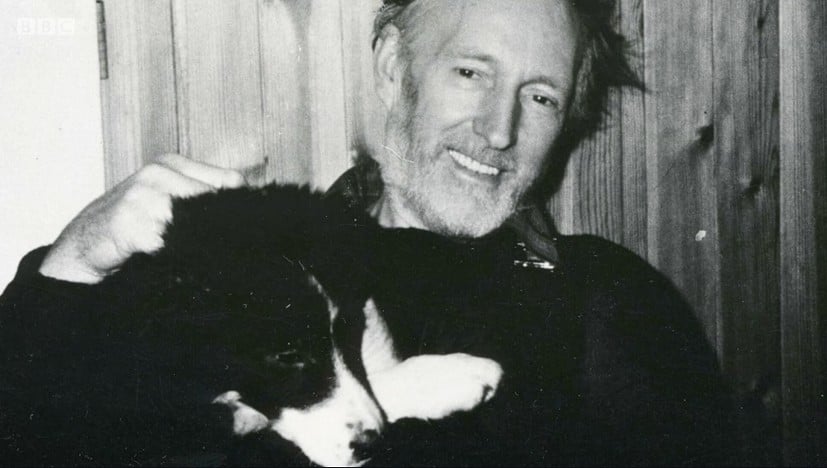

After experimenting with various dog breeds (in particular German Shepherds) to search for avalanche victims, Hamish was responsible for the formation of the Search and Rescue Dog Association in 1965. Always ahead of his time, MacInnes recognised the serious danger posed by Scottish avalanches and worked with Fred Harper and Eric Langmuir to establish the Scottish Avalanche Project. This eventually became the Scottish Avalanche Information Service that provides such an important safety role today.

In 1971, MacInnes published the International Mountain Rescue Handbook, which captured best practice from around the world. It is now in its fourth edition and has never been out of print. He was a prolific writer with perhaps his best-known books being Call-Out, describing his mountain rescue experiences, and Look Behind the Ranges, a selection of his adventures and expeditions from around the world. Equally significant from a climbing perspective were his topo-based climbing guidebooks to Scotland. The idiosyncratic alpine-like grading system confused and frustrated many, but these books opened up Scottish climbing by showing pictures of crags never seen in print before. I recall climbing with Mick Fowler in the mid 1980s and his extreme discomfort when I picked up his copy of Scottish Winter Climbs and noted the red lines Mick had drawn all over MacInnes' crag photos highlighting potential new routes in the North-West.

Hamish's technical safety expertise was greatly sought after by filmmakers around the world and he was involved in many films from the Eiger Sanction to Monty Python and the Holy Grail. In 2014, Hamish contracted an undiagnosed infection which left him severely confused and delirious for a lengthy period. Eventually the infection was diagnosed and treated and to recover his memory he reread accounts of his previous climbs. This led to a series of fresh tales, and a book recounting untold adventures from Hamish's early life will be published by the Scottish Mountaineering Press later this year.

Hamish died in his home in Glen Coe on 22 November. He was 90 years old and had led an extraordinary life. The word 'influential' is often used, but for Hamish, nothing could be more appropriate. From pioneering cutting edge first ascents in Scotland and the Greater Ranges, through development of mountain rescue and avalanche safety, inventing new ice tools and sharing mountain knowledge through his writing and guidebooks, Hamish MacInnes' influence continues to be both long lasting and profound.

A BBC Scotland film, Final Ascent: The Legend of Hamish MacInnes, documents MacInnes' health struggles in later life and is currently available to watch on BBC iPlayer.

Comments

Superb!

Mick

A truly extraordinary man.

The iPlayer documentary is well worth watching.

"a book recounting untold adventures from Hamish's early life will be published by the Scottish Mountaineering Press later this year."

I shall look forward to that.

I should clarify that later this year is actually next year, but it is well underway. Some astonishing stories from Hamish, and wonderful pictures as well.

seems he got an OBE for services to mountaineering and mountain rescue also - well deserved. A legend of mountaineering and inspiration.