Midnight. The four of us stood in a circle and prepared our equipment. I glanced around at Paul, Jim and Nick - watching their eyes dart nervously from behind the narrow slits in their fleece facemasks, as they attached hardware to their harness, uncoiled ropes and clipped on crampons. No one spoke. I felt a deep sense of unease, almost panic. A four-man team is designed more for comfort than speed, and there, under Fitzroy's 5,000-foot Super Couloir, a fearsome route on its vast North-West face, with the temperature way beyond cold, comfort was what we needed.

Why was I standing with these men? Paul Ramsden, Nick Lewis and Jim Hall; they were a tight team who'd put up lots of hard first ascents in places like Alaska, Antarctica and the Himalaya. They were gnarly. Hard men. I hardly knew them and I certainly didn't want to climb the route. What was I about to do? It was suicidal, but I knew I wasn't strong enough to speak my mind. They'd asked me to come, seen something in me they liked or needed, and I couldn't back out now, even if I wanted to. I didn't realize that each thought the same.

All I could think about was her.

Mandy had always been obsessed about having babies. One of the first conversations we had - she told me she just wanted to sleep with loads of men and have loads of babies. I thought she sounded like my kind of woman. I managed to avoid the whole-baby making part for nearly ten years, arguing like most couples that it was never the right time. I didn't realize that there is no such thing. I suppose I knew my game was up when she told me how, when she saw mothers with their children she wanted to cry. I've never been good at thinking long-term and so we agreed that we'd give it a go.

Ploughing upwards through knee-deep powder, we were soon swallowed up by the narrow boilerplate-sided couloir which cleaved its way up the dizzying wall. All around us we glimpsed, in the weak beams of our head torches, the relics of other attempts: bleached strips of dissembled rope hanging frozen and stiff from flakes like old battle flags. Pegs, cams and wires sprouted from the walls, a gallery of lost climbs. I thought about the story of a climber finding a body sticking out of a crack, here, on this wall. Its hair blowing like the ends of a tattered old rope as they moved past. I kept my head down and climbed.

Midnight. The contractions began. Mandy woke me up and asked me to start timing them, but by the time the next one arrived I'd fallen asleep. Frustrated by my lack of interest she pushed me out of bed and told me to ring the hospital and put on the Sound of Music to take her mind off what was happening. With phone in my hand I sat naked on the stairs and shivered. Waiting for someone to answer. I felt unmoved by the coming birth. I wondered if something was wrong with me.

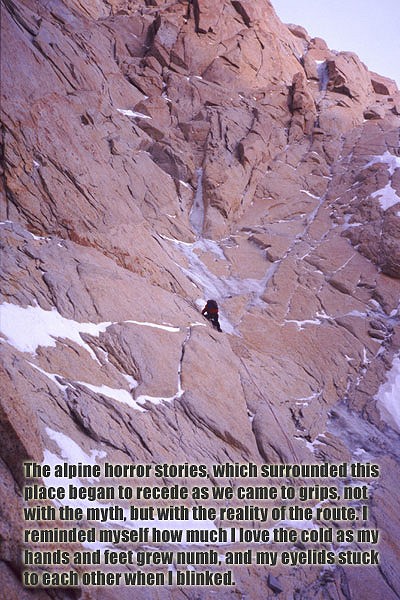

It was too cold for the snow to melt and transform into ice, so we moved together up snow-covered slabs for the first thousand feet. My fear and doubt were quickly replaced by the strain of heavy rucksacks, worries about cold feet and surprisingly enough, the simple pleasures of climbing and of moving quickly through such a place. The alpine horror stories, which surrounded this place began to recede as we came to grips, not with the myth, but with the reality of the route. I reminded myself how much I love the cold as my hands and feet grew numb, and my eyelids stuck to each other when I blinked. My face stung where the cold licked around the edges of my balaclava. The light from the moon, silvery and dead, shone down on the blank walls all around us - illuminating the toothy towers and ice cap beyond. It felt unreal, reminding me of an airbrushed sci-fi poster, so harsh and alien. Another world.

I've always found that I had to be pushed into everything. Getting married, buying a house, learning to drive, and perhaps having kids was no different? I hoped like all those other things I'd eventually shrug my shoulders and think "well it's not as bad as I thought". Mandy once asked me what I wanted most in life, and without thinking I answered "for you to be happy". I suppose I knew it was inevitable, and she wanted a baby more than me. It was that simple and I knew it.

Each pitch was harder than the last with snow giving way to old, fragile ice. The couloir became narrower, the ice running down it no more than a delicate vein of possibility. With one foot on ice, the other balanced on a vertical band of loose diorite, we cautiously tapped our picks into the thicker smears and hoped for the best - never sure we'd reach a solid belay before the rope ran out. Anchored to a poor ice-screw and a old peg, I stood on my side points, trying not to put any weight on the belay as Paul made slow progress up a 70° corner. With no protection between us save for the belay, I forgot about my cold feet as I watched him scratch at the ice, carefully piecing together a shaky sequence of delicate, balancy moves up a foot wide, inch thick strip of ice. Jim and Nick eyeballed us from below, both cut and bruised from the ice we were sending down. Neither of them said anything. We knew what would happen if he fell. All eyes were on Paul's crampons. Without warning, a foothold broke as he weighted it, knocking me onto the anchors as it whizzed past. It held. Paul wobbled on one front point, the weight of his rucksack unbalancing him. Then with extreme care, stacking his feet, one above the other, he moved up, and regained his balance.

"The ice gets thicker up here and I can see a peg!" he shouted down in a wobbly voice.

I looked down at Jim and Nick and felt cheered by their smiles of relief.

The whole baby-making thing turned out to be quite fraught. Mandy became obsessed, going through pregnancy tests like a junkie gets through needles. Nothing was happening. All of a sudden it went from a love thing to a chemistry thing. I hated it. Hated the way I was suddenly forced to produce a baby. When the time was right(but I wasn't) she'd tell me to just get a 'hard on' so she could sit on top. When I refused she'd get upset at me being so unreasonable. A baby had to be made and I wasn't doing my part. As time passed I began to worry that maybe I couldn't, and with that came the crushing reality that maybe it wasn't my choice.

I wondered what she was doing right now, if she was awake or sleeping. I wondered if she was thinking about me. Jim sat next to me and slurped down some half cooked noodles, passing comment on their unusual gritty texture. Until this trip I'd never met Jim, or even heard of him for that matter, yet I was told that he could suffer. On the flight from Britain he'd told the story of how he and a friend had made a unsupported alpine style ascent in Alaska; of Denali via the South Buttress and South-east Spur. The ascent and descent, followed by the walk out to the highway, had taken 28-days. I'd asked him how you climb a route with that much food and fuel. "It basically involved carrying fucking enormous rucksacks and eating next to nothing, which was just as well as the food got soaked in fuel anyway" he explained. On the death march out, half starved and stalked by bears, they'd lost what little food as well as most of their equipment while crossing the McKinley River. When they reached the Alaskan highway they were more dead than alive. "How's this compare?" I asked. "That was nothing compared to this crazy trip" said Jim as he cast the sandy dregs of his noodles into the darkness and slumped over asleep almost immediately. lthough forced to sleep in the most ridiculously uncomfortable manner possible, my feet standing in my rucksack so I didn't slide of the ledge and head resting on my knees, I soon joined him.

Pregnancy began as a blue band almost too faint to see, but there was no doubt. Mandy jumped around and shrieked with glee, her dream finally coming true. I stood trying to look happy, and do things that fathers and husbands are supposed to do. Deep down I felt scared, with a growing sense of unease. The only thought I had was of escape. This baby that grew inside was simply that, four letters that meant nothing to me. It was Mandy's, not mine. It was what she wanted, not what I needed. I began to think that I had to leave, that we had to split up before it came. A friend told me that kids did signal the end of your life, but also the beginning of a new one. It sounded like a nice idea, but I could only see the negative. I realized I had a problem with commitment. I found it hard enough being committed to one person! I couldn't handle the responsibility of a baby as well! But why? What held me back? I hated feeling like this. I wasn't bad person, but my thoughts were so dark. All I could do was keep my head down as Mandy's baby grew.

The sound of the wind forced itself into my dreams like the roar of a jumbo jet engine. I didn't know it was real until I woke to find there was no moon nor stars, only that unreal roar in the black emptiness of space above us. "Oh fuck" I said, waking the others. A storm was approaching. I knew that we should head down. This route was a well known death trap in bad weather. But we had put so much effort to reach this point, with over a kilometer of climbing below us. How could we turn back now when we knew we were so close? The wind was striking the other side of the mountain, so we still had time to escape. There was no doubt that that was the right course of action. Every one wanted to go down. Yet because we took this for granted no one said so, and so each of us assumed the rest wanted to carry on. Insanely, this is what we did.

Moving together we scrambled over huge icy blocks that lead us out of the couloir and up to a notch on the East Ridge. We held on tight as we pushed our heads into the ferocious winds and looked down on Cerro Torre far below on the other side. Unable to congratulate each other under the white noise of the wind, we sheltered behind a block and waited for Nick and Jim, our faces warmed by big stupid grins. All together again, Paul took a deep breath and led an exposed pitch on weather formed nubbins out of the notch, traversing up onto the north side of the ridge and back out of the wind. Gear flapping, his ropes arching out horizontally, he looked like a stunt man climbing out onto the wing of a jumbo jet.

Once back in the shelter of the ridge we tiptoed out above the couloir, traversing towards the final col from were we could scramble up to the summit. It looked as if we could be there in minutes, until we found our traverse ended and we had to climb up onto the ridge. Nick went up but was soon back, unable to breathe in the wind let alone climb. It was 4.30pm and already the sky was growing darker as we huddled together, aware that it would be impossible to reach the summit in this wind. I wanted to go down, I'd fulfilled my half of the bargain, but the others wanted to try and sit it out, gambling that in the morning the wind might abate enough let us make a dash for the summit. I knew that Patagonian storms often lasted for months, the thought of staying here any longer made me feel sick.

Telling people your wife's having a baby was a real rite of passage, like telling them you'd just pulled off a big climb. They know that you're a man. Having children means you're different, you've made it, fulfilled your biological duty. The only problem was I'd see dads at work, looking fat, tired and fed up, complaining how having kids had quashed all their dreams. People would tell me that I'd have to settle down and stop climbing, that once you have kids your priorities changed. No more hard routes. I had so many things I wanted to do.

Scrambling down to a patch of ice perched above the one and a half kilometer drop to the glacier we began hacking out a ledge for our the tiny three person bivy tent. Within a few minutes of squeezing inside, the flimsy fabric strained against its ice screw moorings as the first titanic gust of wind hit us. As the wind moved around and began to blast our side of the mountain, we realized we were trapped until the storm blew itself out, or we were blown off the face. The fabric began buckling wildly, as if a million scared seagulls were striking it from the outside, the edge where our feet lay lifting and falling as fingers of wind found their way beneath us. The wind grew. It roared louder then I'd ever heard, it roared even louder again. Then the tent lifted and we were airborne. I imagined her face. It was the last thing I wanted to see.

Mandy started bleeding in the morning. She was only five months pregnant. It was a bad sign. We were staying in London so went down to the local hospital and waited in the accident and emergency department. Mandy cried, fearing her baby was dead. I put my arm around her and felt like crying but stopped myself. I had to be strong. I felt a deep sense of sadness at the thought of her baby dying. I knew how much it meant to her and I wondered if she would fall apart, if we would fall apart, if it had died.

The tent tumbled as if it was in wild surf. I heard people screaming and realized I was one of those people. I held on to Paul at my side, convinced we were now tumbling out into space, about to be smashed to pulp as we rattled down the face. We crashed back onto the ledge. The anchors had held us.

The doctor slid back the curtain, and smiling, told us that everything looked fine and the baby looked very healthy. There was nothing to be worried about. I felt relived, wanted to shake his hand, everything was OK. Mandy wiped away the tears. She looked beautiful when she was happy.

Midnight. Time stretched on long and terrible. The tent was blown in the air every 10 minutes, while the inescapable noise of the wind and the flapping fabric drove us crazy. My body's supply of adrenalin soon ran dry. Unable to cope with the stress, my brain began to shut down. All I could think about was my foolishness, about her love, about what this would do to her if I was to die. I wished I didn't care, wished I could just be remorselessly selfish.

Dawn arrived but the wind only intensified. I shouted that we should fight our way down while we still had some energy but the others out-voted me, saying we should stay where we were. Fear gave way to numb resignation and we began to shout out stories of other epics we'd come through. We all doubted we'd live to tell this story.

After seventeen hours, the conversation slipped from epics to the mundane and inevitably to sex. Nick began describing his difficult love life, telling a story of how once on a climbing trip to Poland he had been propositioned by a beautiful, famous ballet dancer in Warsaw. "She was gorgeous, but I already had a girlfriend in England and I told her I couldn't be unfaithful"'. "Did you tell your girlfriend about it?" asked Jim as the wind slowly withdrew and the mountain became almost silent. "Yeah, when I got home and rang her to tell her how faithful I'd been, she told me she'd met someone else and it was over!" In our heightened state of fear we started to laugh hysterically as the wind returned stronger than ever and began tearing into the tent. With tears rolling down our cheeks we were laughing not only at Nick's lack of luck with women but at the thought of four crazy men talking about sex and ballerinas while trapped on Fitzroy in winter. It was then that the tent began to rip apart.

Our lodger John took us to the Hospital. Mandy lay in bed in pain while I tried to stay awake beside her. The day dragged on with no sign of any birthing. Busy doctors and nurses popped in every now and then to check on her condition. I walked up and down the corridor, looking at other tired dads. None of them seemed too keen on the whole deal. I went down the hall and rang all the people I needed to keep informed, then sat next to Mandy. I tried to talk to her, to do what fathers are supposed to do, but I was only a distraction, so I sat and read instead.

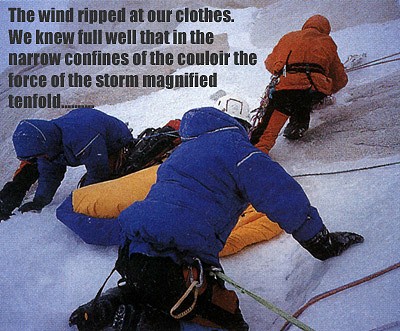

One minute we were in our sleeping bags laughing, the next we were screaming as the tent filled with spindrift and then began to disintegrate around us. My sleeping bag turned into an icy windsock. I furiously stuffed it into my rucksack and then squeezed out into the raging storm, holding on to a tangle of frozen ropes. It felt as if I was in the rigging of a ship battling around the Horn. The wind roared in triumph. Hoar frost instantly covered everything. I watched as Nick, and then the others, appeared each face hidden behind multiple balaclavas and goggles, all of us dressed in our huge belay parkas. The summit was totally irrelevant now as with gravity seemingly reversed, we found ourselves at the top working out how to climb downwards. Holding on to anything we could, we slowly retraced our steps back towards the brèche and the couloir. We had no idea where the other descent routes were, we had no choice but to go back down the way we'd come. It was the last place on earth you would want to visit in such a storm; it was a death sentence, but it was our only escape route.

I flicked through an Australian magazine and did a bit of homework, reading about a winter ascent of Fitzroy's Super Couloir, a route I planned to try that summer. I was uneasy about the trip, my first proper expedition. I wondered how I would get on with Nick, Jim and Paul, guys I'd only met through work. I'd thought about going to Patagonia in winter for a long time, but I'd never found anyone to share my enthusiasm, that was until I mentioned it to Paul one day when he came in to buy some new crampons. His uncle had traveled around Patagonia one winter and said the weather was much more stable, and so we began to organize the trip. Patagonia in winter - it was still a crazy idea. I thought how I'd now be the only dad on the trip and wondered if being a father would make any difference, slow me down or make me more cautious? A nurse came in and said I should go home. I'd been up for 24 hours and she doubted Mandy would have the baby until tomorrow. Glad for the chance of some sleep I slipped away.

Midnight. The phone rang. I had been in bed for less then 15 minutes. "Mr. Kirkpatrick you need to get here as soon as you can, your wife is giving birth". I put the phone down and lay my head back on the pillow. The phone rang again. "Mr. Kirkpatrick are you on your way?" This time I jumped out of bed. When I reached Mandys' room she was in full labor with a doctor and midwife helping her. The birth had been long and with complications, the baby twisting inside her. I stood next to the bed and tried to hold her hand but she told me to fuck off, so I sat passively and watched. The labour went on. I felt detached. I felt nothing.

Watches froze, time stopped for all of us as we slowly descended. Each of us was alone with our fears. There was nothing to say and very little chance of anyone hearing it anyway. We thought no further than the next rappel and blessed our gods each time the ropes come down. The thought of losing our ropes to the storm; blown off and snagged on unreachable flakes, or chopped by falling rocks, was unthinkable. Trying to avoid the couloir as much as me could, we risked a faster plumb line down blank walls: quicker, but totally committing. We could only guess where we were, the walls now uniformly white with feathered hoar, thick cloud swirling all around us. At one belay, three of us hung from a small wobbly flake and a single peg, our feet dangling in space, as Paul looked for another anchor below. We knew there was worse to come and accepted it for the chance it gave.

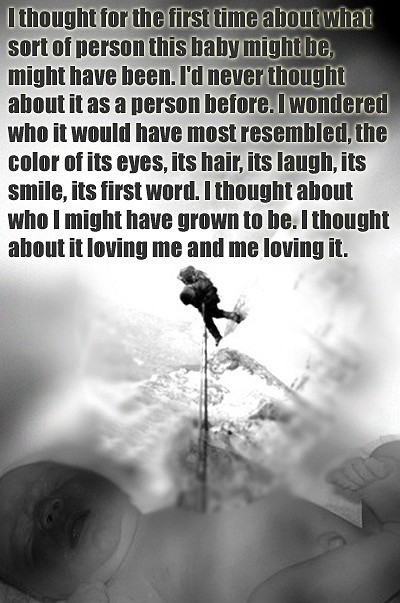

Mandy's screams and shouts grew with the pain. The midwife looked worried and began to sweat. The doctor came back in the room. They talked. I stood up and tried to work out what was going on. "Mrs Kirkpatrick...Mandy...we think the umbilical cord might be around baby's neck, we need you to really try and push". I started to cry. I grabbed Mandy's hand tight and squeezed it. I willed the baby out. Her face turned red. I couldn't stop crying. I didn't want our baby to die.

Unwilling to break out the two other ropes and risk them becoming stiff and frozen too soon, we descended slowly together, rejoined the couloir and scratched across the wall to a familiar belay. Once all there, we stayed silent until we retrieved the ropes and then relaxed a little; now we had a familiar route to travel, even if it held many dangers - a bowling alley of rock and snow. I took a photo and Jim smiled. I wanted to believe I'd live to see it. "I think it should be about 30 raps from here" Nick said as he slowly lowered Paul into the upwards-driven hail. The wind dropped for a second and we were immediately blasted by express trains of spindrift. Resigned to our misery, the three of us hung limply off the belay as Paul searched below for another anchor. All of us were half buried in the swelling tide of snow. Don't think any further than the next anchor I thought. It was a good strategy.

The midwife urged Mandy to push harder, and somehow she did, then said she could see the baby's head. I looked away, being a coward, and because I was terrified about what I might see. Maybe if the baby was dead, and I never saw it, it would remain unreal to me.

Only the arrival of night signaled that time was still passing. The world was now no bigger than the flickering circle of light from our headlamps. We had lost count of the number of rappels we'd made. I was numb, both psychically and mentally. I thought about reaching the glacier and our tent, but the thought was torture, the possibility seemingly no nearer than when we began. I wondered if we had already died and this was how we would spend eternity.

I stood unable to move, just waiting for the moment to pass, whatever would happen to happen and resolve itself. If the baby was dead we'd get over it. There would be time for other babies. God what was wrong with me? Why was I so detached? SO scared? Did my father feel like this when I was born?

Fourteen hours since this hellish descent began, I climbed down alone, too cold to wait my turn on the endless rappels. Barely in control, slipping and arresting, my headlamp almost as dead as my brain, I heard another pulse of wind break against the face. I stopped in my tracks, as I waited for it to pass. The sound was utterly terrifying, bringing back dark memories of being washed into the sea as a child one stormy Christmas.

I leant into the slope to rest my back, pressed my head into the snow for a second and wondered how far I was from the bergschrund. Without warning a spindrift avalanche poured over me, choking and blinding. I panicked, slipped and disappeared into a soft helter-skelter of snow that swooshed me down into the darkness. I came to rest just over the bergschrund and crawled away, too exhausted to think myself lucky. I kept trying to stand but each time the wind kept hitting me, knocking me over, until all I could do was crawl away utterly defeated. Jim caught me up and passed on by, wrapped in his own sense of survival. Then the others. I got to my feet and staggered along behind them into the night.

The midwife began to say 'wait', but it was too late, the baby escaped out into her hands. I turned to see it - I couldn't help myself. The midwife's head was bent down, stroking this grey dead thing. She was crying.

I'm hallucinating now. I see Napoleonic soldiers staggering along beside me, rifles dragging in the snow. I think about the torture of knowing you would never make it home, no matter how hard you try. The dying image your wife and children waiting for you.

I plunge down through the snow, glad of the quickly filling tracks left by the others. Every few meters the wind knocks me over, but I know it's lost, it can't kill me anymore, I've won. I've rationed my energy well, I've had to do it many times before, but I've never felt this empty. Purged of emotion, no more feeling of self, my insides have shriveled into knots of muscle. I'm totally empty. I'm about to stall. The wind blows me on now, back towards our base camp. I think about our nylon oasis, of tea and biscuits, of light and laughter about this crazy climb. I think about home.

I blinked hardly believing this was happening, then blinked again when I saw a change. Wanting it to be true. The baby was turning white, then pink. It opened its mouth, its hand jerked, its tiny body danced in the arms of the midwife, who raised her head and whispered 'She's a girl'. My daughter. Ella.

Midnight. We kneel in a circle in the snow. This was where our tent had been. Now it's rolling out somewhere on the Patagonian ice cap. There's nothing left but some scraps of material, that flap wildly like severed limbs. I'm too dehydrated to cry, and I know that frozen eyes would only add to my pain. I think about Ella, too young to know where I am, but old enough to know I'm not there. I want to be with her, not here with these strangers. I think about those soldiers I'd passed stretched out across the Steppe, and of lives, new, old and changing.

Comments