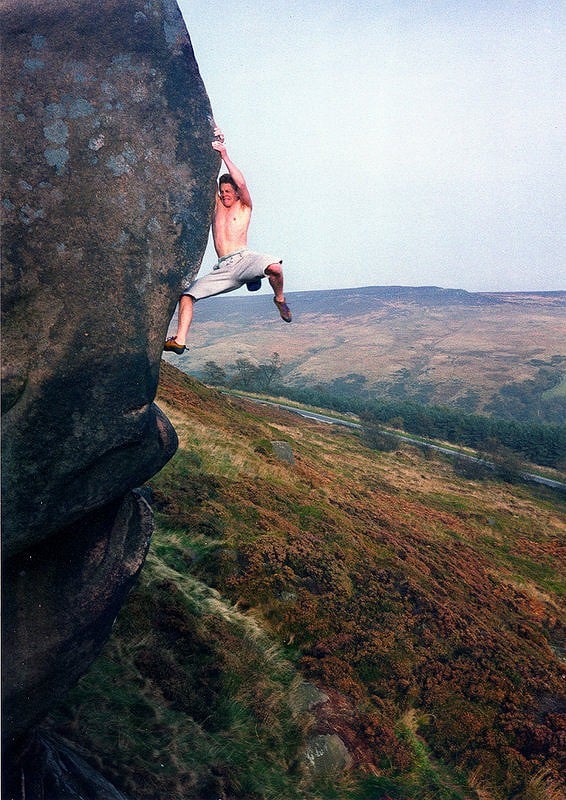

Julian Lines - 'The Dark Horse' to many in Scottish circles - has a reputation for soloing bold routes which goes before him. He isn't sponsored, nor does he have a Twitter account. As one of 'the best climbers you've never heard of,' Julian's understated nature is at once typically British, yet atypical of a top climber operating in the extreme art of soloing.

In his Boardman Tasker Award-winning book Tears of the Dawn, Jules writes about his climbing life with acute attention to detail. Whether in the wilds of the Cairngorms, on an exposed sea cliff or on a tamer gritstone edge, it's clear that Jules has an innate ability to control his thoughts when soloing a hard line, with intense focus and determination to boot.

His introspective perceptions on climbing coupled with his quiet demeanour intrigued me, so - using his book as a guide - I asked Jules some questions to find out what really makes him tick.

"I can’t have wars going on in my head when I’m soloing close to or at the limit, that’s almost suicidal."

Climbing all 277 (at the time) Munros in 5 years by the age of 18 through your school, hillwalking was an early passion for you. How did your enjoyment of the hills transition into bold rock soloing?

I would say that I didn’t have much of a family life and I daydreamed a lot and put all my efforts into walking and being out in the hills. Hence the hills sort of became my home (I don’t have any regrets about this). I’m not sure what happened when I finished the Munro’s or why I merged into pure rock climbing rather than mountaineering. It was probably down to a cost thing. I wanted to be out in the hills at all costs and sometimes with climbing I didn’t have people to climb with and that sort of curbed the freedom. Therefore I wandered into the hills alone to enjoy the freedom and soloing started at a sedate level, and you know how it is, it becomes addictive and hard to control like a drug. The next moment I’m soloing quite hard stuff, quite high up without realising it.

You describe your difficult upbringing, being educated at boarding school without a mother and having a disciplinarian father who saw you and your brother as a 'disappointment.' Do you think the circumstances of your early life were an impetus for your 'frighteningly powerful' self-motivation?

Yes, I would like to think so, but I’m not sure that is the case. My brother and I had very similar upbringing but he’s not as motivated as me (dare he see this). So, I’m probably going to contradict myself here and say that I guess my motivation has come from my genes, both my mother and father are/ were very motivated in their own ways and I guess I inherited and focused it in a totally different way. The upbringing probably shaped that focus in an additional way.

'Character, like a photograph, develops in darkness.' How did climbing help you overcome darker periods of your life?

I think the early days in the hills erased a lot of the darkness in my life, or gave me little time to dwell on it. The bold climbing later on probably eradicated the remainder of it because you have to be so focussed there is literally no margin for error and no room for darkness.

You mention your 'reclusive tendencies,' how important is it for you to seek solace and adventure on your own and why does it help you? This seems very rare a society where sharing and social connection is deemed essential - perhaps most people lack the courage to experience things in isolation?

Yes, this might be a bit of a misconception here. I am more gregarious than people think, especially in good company and for short periods of time. However I do like spending time on my own, especially out in the hills. It’s the only way you can truly appreciate the natural world. I agree that soloing needs a good degree of detachment, it is certainly hard to focus on a solo when chatting or in company with other people. Over the years I have become comfortable with being on my own. In a perfect world it would be good to have solace during the day and good company in the evening.

I’m not entirely sure that people lack ‘courage’ to do things on their own, but rather have never tried or actually never thought about leaving the comfort zone they are used to.

You mention meditation and connections to the spiritual/supernatural world. Would you describe yourself as a spiritual person, and if so how does this influence your climbing?

This is a very interesting question and one that might be wrongly diagnosed if reading my book. I’m more like a cold blooded reptile that likes to sit out and meditate in the sun especially when I am ‘relaxing’ inbetween climbs, but when I’m preparing for a big solo I find it increasingly more difficult to meditate, I have little patience and it’s so difficult to find that realm of peace and harmony in the mind because lurking in the back of it is the knowing that if it all goes wrong, life is over.

On the spiritual front, I can’t say that I am a Yogi or even pretend to be, far from it, but being alone and watching nature and the world going on around me gives me a feeling of spirituality that in its way gives me a kind of comfort before and during a solo.

Your work as a rope access technician has seen you in all corners of the world, from Brazil to Australia and beyond. Do you think you would have had an urge to travel to such far-away locations had you not been employed in this industry?

Yes and no. I would say that I am a workaholic at heart (probably genetic). Seeing pictures of beautiful climbing destinations around the world in the media aspired me to go to these places, but there is a certain practicality about me, and I would refrain from going because I always felt that working came first. So being able to travel with work sort of helped greatly. However the older I get, I am realising that life is too short, and fulfilling those aspirations of visiting places I’ve always wanted to go is becoming more important than a healthy bank balance.

Your studies of geology at university are alluded to throughout your book. Does your knowledge of the properties and geological history of the areas you climb in add to the experience?

I wouldn’t say the geological history does add much to the ‘experience’, although having a basic understanding of the geological processes is better than being totally oblivious to them. I would say that I have an affinity (like many climbers do) to rocks, their textures and the shapes of the holds they form though.

"I’ve always been very controlled with my climbing, I’ve never seen it as a gamble, maybe once or twice I’ve risked more than I should have on a climb but it has always been within a sane boundary."

Gambling - in the monetary/financial sense as well as on rock - was a real adrenaline kick for you. An obvious parallel can be drawn between gambling with money and gambling with your life on a solo - did you view soloing as a 'gamble' or was it more considered and controlled?

I wouldn’t say my gambling was really gambling! It started as low risk investment gambling (although with relatively large sums of money), which did get a little bit out of hand. The amount of money I could lose (because I’m quite frugal) was more the adrenalin kick than the gambling if that makes sense. I had never gambled before that time (aged 36) and never gambled after, so my gambling life lasted about 8 months in total whereas I’ve been soloing for 25 years. I’ve always been very controlled with my climbing, I’ve never seen it as a gamble, maybe once or twice I’ve risked more than I should have on a climb but it has always been within a sane boundary.

Soloing is a war of the 'state of the minds' for you, involving both your conscious and subconscious mind. How would you describe the interplay between your conscious and subconscious mind when soloing a hard line?

That’s a very perceptive question. Let's take, for example, a route that has been practiced or headpointed. I think in those circumstances it is easier because the more practice, the more confident I become and the more relaxed my subconscious mind becomes overall. I can only begin the solo when my subconscious mind is fully at ease because I can’t have wars going on in my head when I’m soloing close to or at the limit, that’s almost suicidal. Onsighting is very different, the climbs are usually easier and both your minds have to be more alert and open to compromise with each other.

You have dabbled in other extreme sports such as free diving, BASE jumping and paragliding. Why has climbing dominated - is it purely because you have done it for a longer period of time?

Probably because it is more natural and easier to partake in than the others, especially in this country. I am also very intolerant of faff and BASE jumping and paragliding require a lot of faff with equipment as such. Free diving is more similar to climbing, but the water is too cold here and there are only a few good specific places around the world to do it whereas climbing is everywhere.

"All I know is that if I set out on a climb, I won’t give up, which can be a very dangerous way to be, but offset against that is my control that keeps me alive."

"I have always been conscientious and had an innate work ethic"[...] "It just wasn't in my nature to quit" - do you think your hard-working and perhaps stubborn character is a key ingredient in your climbing?

Yes, I think so. I don’t think I’m as good as many other climbers out there and I’m surprised that I have managed to climb some of the hardest routes around. I think that is down to persistence and the will to succeed and, dare I say it, with as little training as possible, I just don’t like training, which sort of contradicts the question.

You openly admit to being afraid on solos - you don't pretend to be superhuman! What do you think makes you keep pushing and coming back for more where others would succumb to fear?

To be honest I don’t know the answer, I wish I did. All I know is that if I set out on a climb, I won’t give up, which can be a very dangerous way to be, but offset against that is my control that keeps me alive. I must add here that I don’t push myself as much as I used to and I’ve stopped soloing big (long) climbs. Maybe writing the book has been cathartic for me and I now realise that I don’t need to do this anymore to prove anything to myself or anyone else for that matter.

You appear to be very in touch with nature, animals and your surrounding environment. Do you see this as an integral part of the soloing experience, perhaps moreso than on a trad or sport route - the need to be perceptive and aware?

Yes, definitely. When you are on your own you become very in tune with nature as there is little else to relate to. With trad climbing, you are thinking more about your ropes, extending your runners, worrying if the gear is going to fall out, searching for the next gear placement, trying to hang on or shake out a pump etc…with sport climbing it’s all very intense and physical, always trying to drain the last ounce of energy out of your body etc…there is no room or time to absorb your surroundings in those situations. With soloing there aren’t any distractions like those mentioned above so you could probably hear a fly break wind…

Your descriptions of your experiences suggest a highly active imagination. Which one experience stands out above the rest for you as being the most memorable?

I could spend a lot of time mulling over this question, but one of the reasons I started to write was because there were some strange stories or predicaments that I landed myself in that needed to be told. However I’m not sure memorable is the right word as some of them were harrowing rather than memorable. But I suppose the time when I started to get benighted on the Dubh Loch and took my 4mm chalk bag cord off and tied one end round my wrist and the other end I knotted and stuffed into a crack to stop me falling off a ledge 200ft up if I fell asleep.

You mention feeling safe from the pressures of the outside world in nature, attempting to 'escape from a world revolving around materialism and consumerism.' Climbing as an activity is renowned for attracting rebellious and revolutionary characters, thinking of the early Yosemite days. Do you think that climbing has fewer wandering 'rebels' these days, people who actively avoid the trappings of modern society and the rat race as far as possible?

I think society has changed so much since the 70’s. Ultimately we all have to live and that means we all have to work. I think there are just as many ‘characters’ now as there were then, but they haven’t got the same field to play on as before because ‘life’ has changed. I mean, claiming the dole in the 80’s during Mrs Thatcher’s years was the last time a mass of climbers could really be ‘climbing bums or ‘rebels’ as you put it. Now the only opportunity to be like this is to either be sponsored or to work hard and play hard and try and balance it, like a lot of rope access workers do I suppose. As someone once said of me, I’m an affluent hippy.

Speaking of bolting, you talk of human beings' desire to 'colonise'. Can you describe what this means in the climbing sense? Are our instincts to control our environment detracting from a more 'natural' and raw experience?

I think humans have this colonise/ ownership/ territorial gene, which is due to the ‘evolutionary drive’ that all creatures have. So I think in a climbing sense, if there is a piece of unclimbed rock, in our heads we need to climb it, and if we can’t do it naturally we then stick in metal pins so that it can, then we stick names and grades on it. It’s all kind of incongruous really.

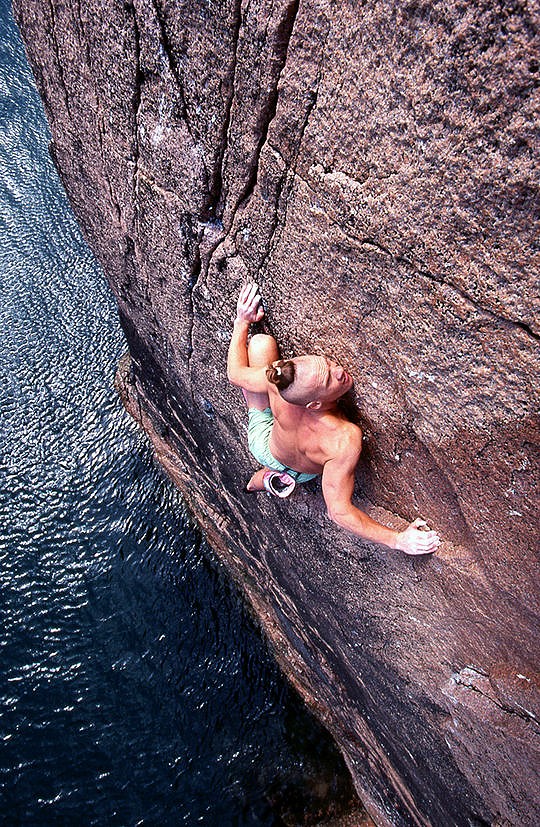

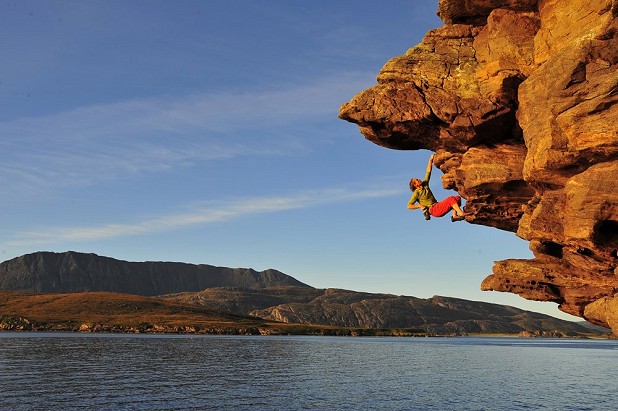

However going into the wilds of another country and finding a piece of rock and just climbing it with no ropes or anything for the thrill is an incredibly intense experience. There is no ownership, no rules, just the human movement and its mental counterpart working together harmoniously. It’s very purifying.

"Who knows what the future will bring, but I’m not fighting the loss of my soloing mojo at all. It’s certainly healthy that way."

You now feel less inclined to taking risks on solos, as you are 'dutifully bound to older age' and appreciate the fine line between life and death. Can you explain what you mean by this - how has your approach changed and why?

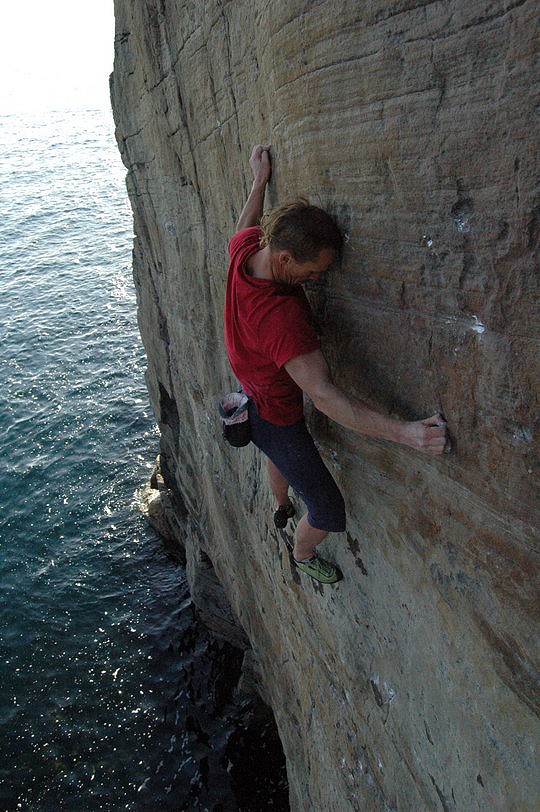

I don’t have the urge to solo high up (above 50ft) anymore, perhaps it is age, perhaps I’ve lost some mojo, but it doesn’t float my boat anymore, so why do it? I’ve nothing to prove to anyone. Climbing is such broad church and it’s nice to experience or enjoy other facets of the sport or indeed other sports, which I have done in the past. With climbing I have always been drawn to bold and technical climbs rather than physically demanding ones and I have come to be happy with deep water soloing or working routes on a rope (headpointing) before leading or soloing them now. Who knows what the future will bring, but I’m not fighting the loss of my soloing mojo at all. It’s certainly healthy that way.

'Except our own thoughts there is nothing absolutely in our power.' Descartes. When soloing, your fate is decided by your ability to keep calm in the face of breaking holds, weather changes, footslips and fatigue. What goes through your mind at a critical point on a solo?

Soloing is all about complete control, both over your mind and your body and there are a few different scenarios.

Firstly, on attempting a very difficult pre-practiced climb, the subconscious mind will be meticulously calculating and risk assessing whilst it is being practiced on a rope. Only when the subconscious is 100% happy will it give the green light and then the minds shut down and are calm, you just climb without any mental pressure.

Secondly are the routes that are not pre-practiced and then you have to be ready at all times to employ plan B (a safety valve in the head), and this is to be able to ‘reverse’. I have reversed a 150ft route once from the very last move because I didn’t want to pull on a dodgy looking hold.

However if you have gone past the point of no return then it becomes a fight, a fight not with the rock, but in the mind. The mind goes ‘numb’ and then the body starts to follow suit. The trick is to have the ability to control this, probably by breathing, or closing your eyes, or by some other method, if you can’t then you are inevitably going to die.

When were you most scared?

Probably ice climbing, 600ft up on March Hare’s Gully in the dark when both axes ripped. Having said that I was only scared for a split second before I realised the inevitable and sort of relaxed.

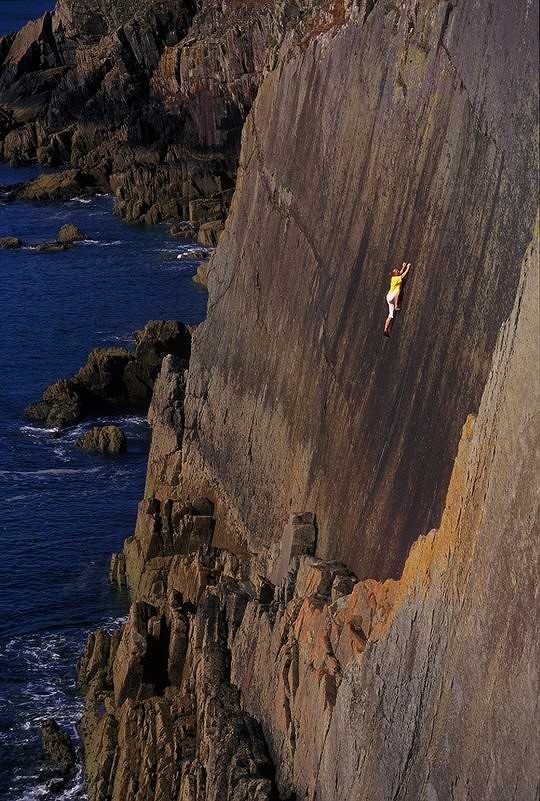

Alternatively I would say soloing up Dilemma / Cling On/ Uhuru on Skye when I was lost in a sea of rock, realising that reversal was no longer an option and then it started to spit with rain. That was a moment when my mind began to go numb and I realised that I was going to die. It’s hard to get yourself to climb when you know it’s ‘pointless’. Yes, I was scared, very scared.

"We only have one life, so it’s not a good use of time to go down the same road with the same view, even if it is a comfortable one."

Which location will you always return to - be it to climb or just to 'be'?

There are a number of places or spiritual homes I have around the world. It has to have a mixture of lovely rock, great views, an ambient feel and wildlife of sorts. I like the Very Far Skyline at the Roaches for the gritstone. Or just losing myself in the remoteness of the Cairngorms, or the wonderful small crags and islands around Erraid on the Ross of Mull, there is so much wildlife going on there; seals, mink, otters, birds, big spiders and dragonflies.

What's next for you? Will you always be a 'wanderer' or 'remontado'?

I don’t think so. Life is a journey and although I’m quite a cautious (or controlled) person, I will deal with the challenges that life throws at me. I’m open to decisions and choices. We only have one life, so it’s not a good use of time to go down the same road with the same view, even if it is a comfortable one. Change is good and change is what builds the character I suppose.

Read a review of Jules' book Tears of the Dawn by UKC Chief Editor Jack Geldard here.

Buy a copy of Tears of the Dawn here.

Watch an excerpt of Stone Free, a film about Jules by Posing Productions here.

Watch a video of Jules' infamous groundfall from Hold Fast, Hold True (E10 7a) below:

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

- ARTICLE: Alexandr Zakolodniy - A Climbing Hero of Ukraine 26 Apr, 2023

Comments