Today (25 May) marks the 65th anniversary of the first ascent of Kangchenjunga (8,586 m) by British mountaineers Joe Brown and George Band. Mick Conefrey, author of the recently released The Last Great Mountain: The First Ascent of Kangchenjunga, shares the story of this historic climb.

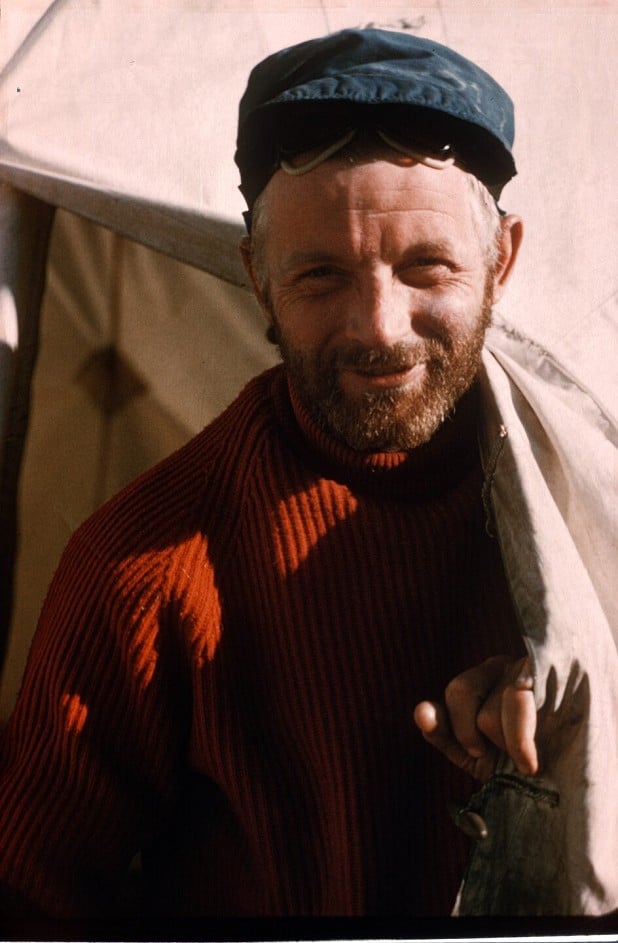

Sixty-five years ago, at the end of May 1955, the Golden Age of Himalayan climbing came a thrilling but unexpected climax. On his first expedition to the Himalayas, Joe Brown, a 24-year-old British climber from the backstreets of Manchester who still lived with his mum, hauled his way up to the top of Kangchenjunga, the world's third highest mountain.

It was a watershed moment, the last of the big three Himalayan giants to be climbed, the first time that a British born climber had stood on the top of an 8000m peak. John Hunt, the leader of the Everest 1953 team described it as "the greatest feat in mountaineering."

During the 1930s there had been three major expeditions to Kangchenjunga but no-one had got anywhere near the summit. Kangchenjunga gained a reputation for invincibility: its combination of extreme weather, extreme altitude and technical terrain made many doubt that it could be climbed at all. But as the great Norwegian explorer Fridjtof Nansen said, "the difficult is what takes a little time, the impossible is what takes a little longer."

In 1954 Charles Evans was offered the leadership of the Kangchenjunga reconnaissance. If he could find a route up the mountain the plan was for a much larger expedition to return in the following year, including several star climbers from the British scene. Charles Evans was determined to do much more than find the route for others to follow; two years earlier on Everest, he and his partner Tom Bourdillon had got within a whisker of beating Hillary and Tenzing to the summit, this time he wanted to go all the way to the top.

Evans assembled a group of eight British climbers who he thought would work well together. The wildcard was Joe Brown, a young Mancunian who was utterly different to the classic Oxbridge or army climbers who had dominated high altitude expeditions for the first fifty years. The youngest of a family of seven, Joe was a jobbing builder who had taught himself how to climb in the quarries and crags of the North West. There were some in the establishment who thought he was too big a risk and lacked big mountain experience but Charles Evans was willing to take the risk, and Joe Brown was absolutely up for it.

They set off for India at the end of February, set up base camp a month later, and painstakingly worked their way up the mountain. The odds did not look good. The Indian air-force sent them photographs of the summit ridge, which showed it to be a ferocious knife edge. Initially they wasted a week trying to find a workable route through the huge ice-fall at the foot of the South West face, before they realised that it would never be safe enough for heavily-laden porters.

There were moments when Charles Evans doubted his leadership skills but he refused to give up and stuck to his motto, 'Dogged as Done it'. His luck began to turn, but even as he and his team climbed higher and higher, they lived with the constant fear that the monsoon would arrive and make climbing impossible. On May 14th, Charles announced his choice for the two climbers who would make the final push to the summit: Joe Brown and George Band, another of the team's youngest members. Charles would stay back in reserve, in case anything went wrong. Eleven days later after a huge team effort to place a last camp high on the mountain, Joe and George were poised at 27,900 ft ready to make the final push.

They left camp at 8.00 a.m on May 25th, 1955 and headed up the 'Gangway, a wide couloir which they hoped would take them most of the way to the top. Having spent the previous six weeks climbing on snow and ice and they now found themselves tackling very mixed terrain with snow slopes interspersed with rock pitches. Alpine trained George Band gravitated towards the snow, Joe Brown preferred the rock. The route finding was not easy; they came off the Gangway too early and wasted an hour of time and precious oxygen.

At 2.00 pm Joe and George paused for the first time. They had reached the West Ridge and according to the plan worked out a few days earlier, had almost reached their 'turn-around' time. If they carried on, they risked running out of oxygen and having to bivouac in the open without a tent. If they turned back, a second summit team was waiting below but there was no guarantee that the weather would hold for another day. Joe and George decided to carry on but soon encountered their biggest challenge: a forty foot cliff with no obvious way up. Just like Everest's 'Hillary Step', Kangchenjunga had saved the most difficult climbing for the end.

If this had been at sea-level it would have been a reasonable challenge, but at 27,900 ft. it required all their reserves of spirit and stamina. The rock was smooth and sheer, with no obvious hand or footholds but Joe Brown spotted a crack in the middle running from the base to the top. His speciality, born of years of climbing in the Peak District and Wales, was 'hand-jamming'. Joe cranked up his oxygen set to 6 litres per second, three times the normal rate and painstakingly worked his way up.

Twenty minutes later he called down "We've made it". George followed him up the crack and together they walked along the ridge stopping just short of the small cone of snow that was the summit. In deference to an agreement that Charles Evans had made with the King of Sikkim, they left it untrodden because of its religious significance for local people.

A day later while Norman Hardie and Tony Streather made the second ascent, a coded message was sent back to London announcing their success. It was a great moment, which made headlines around the world. Over the last six decades, Kangchenjunga has faded into the background. Unlike Everest, there's no 'yak-route' to the summit so commercial operators stay clear of it; only a handful of climbers attempt it every year. The first ascent, however, remains one of the great moments of British climbing history, a small team who went out, as Charles Evans later wrote, determined to reach their goal "under cover of a great deal of laughter, and while having an enormous amount of fun."

- ARTICLE: 100 Years of Everest Gear 14 Apr, 2022

- John Hunt - The Forgotten Hero of Everest? 14 Nov, 2012

Comments

Nice.

Note: Probably just a typo, but "Joe cranked up his oxygen set to 6 litres per second..." should be per minute.