Rebecca Batley writes about the skill and courage of Lily Bristow, and how she defied convention to become one of the most famous women to lace up her shoes and head into the Alps.

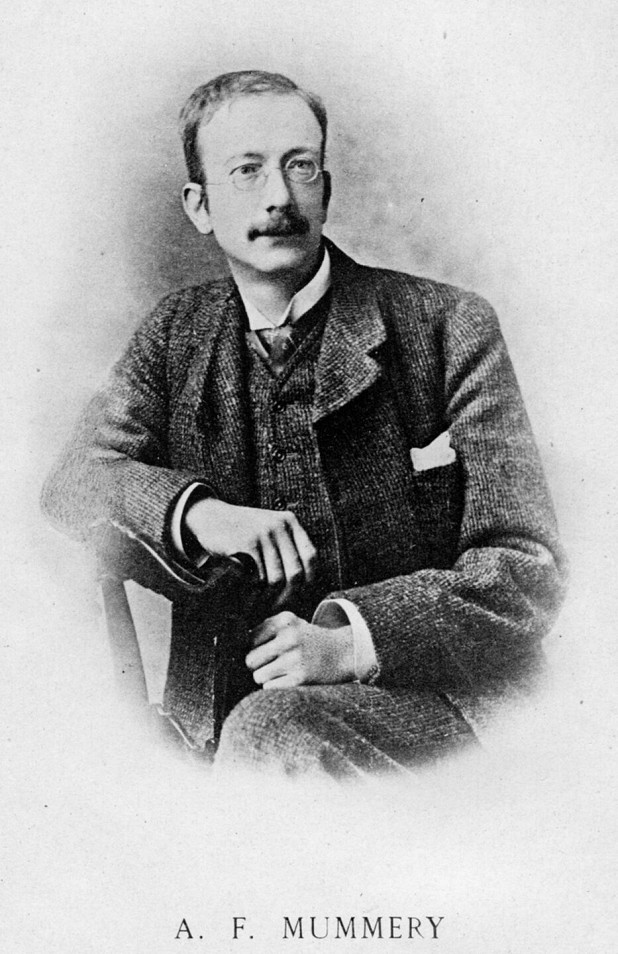

In the 1890's legendary mountaineer A.F. Mummery famously sat down and wrote that 'All mountains appear doomed to pass through 3 stages: An inaccessible peak, the hardest climb in the Alps, an easy day for a lady.' He was not being chauvinistic; rather he was paying an ironic compliment to the skill, courage, and ability of his fellow climber Lily Bristow.

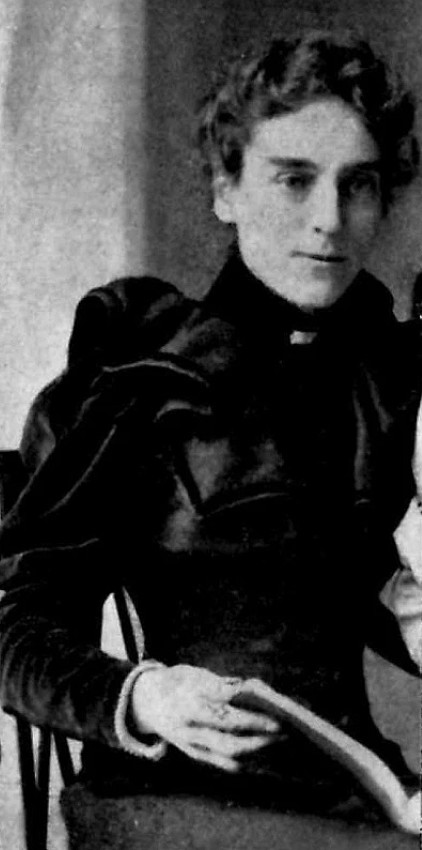

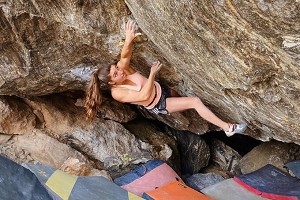

Emily Caroline Bristow, known all her life as Lily, was born in 1864, the daughter of George and Mary Bristow. She was not the first woman to pick up her climbing shoes and head into the Alps, but she quickly became one of the most famous, or rather infamous, as she courted scandal and smashed stereotypes, refusing to live her life by, or be bound by, the rigid limits Victorian society imposed upon women.

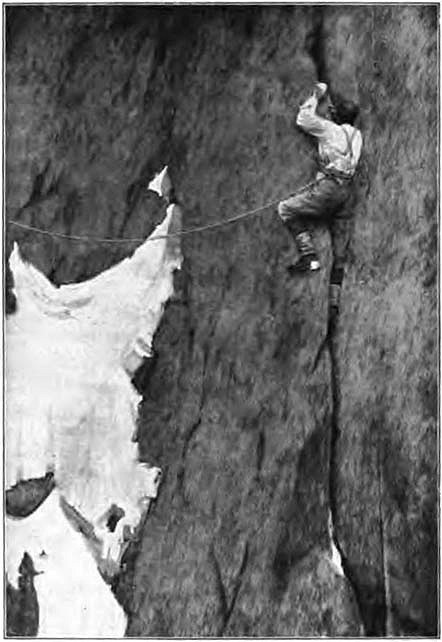

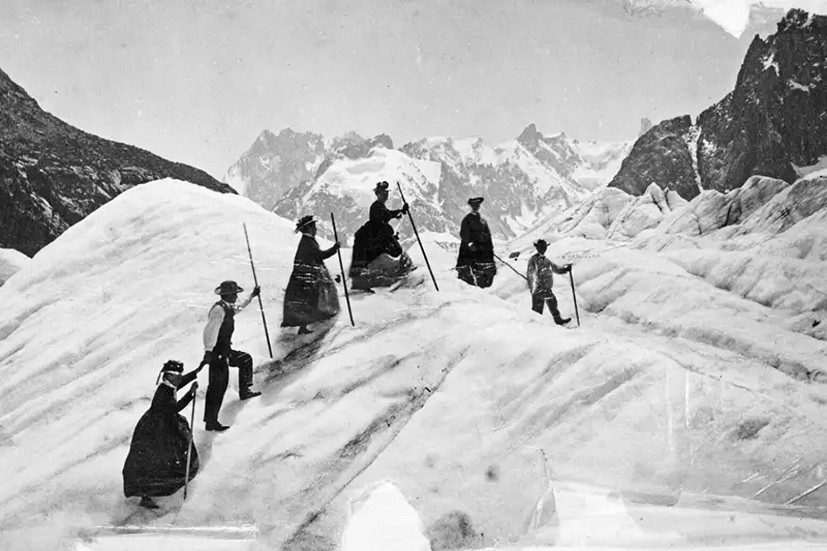

Details about her early life are scarce, but Bristow burst onto the climbing scene in 1892 when she climbed over the Aiguille de Charmoz with the famous husband and wife climbing duo of A.F Mummery - who Bristow called Fred - and his wife known as 'Mere'. That year Bristow became, alongside Mere Mummery, the first woman to conquer the Aiguille des Grands Charmoz. They undertook its dangerous vertical ascent, and Mummery went so far as to insist that women were in fact better suited to such exploits given their less bulky frame.

It was the following year, however, that Bristow really began to attract attention. It was very rare in the 19th century that the climbing exploits of women were reported, for fear of encouraging others, but many felt Bristow's exploits to be so incredible that they began to filter into the local newspapers. An account of many of Bristow's climbing exploits also survives in her letters.

Bristow spent most of 1893 with Mummery, and on the 6th August 1893 she wrote:

Rejoice with me, for I have done my peak! The biggest climb I have ever had or ever shall have for there isn't one to beat it in the Alps… the expedition I'm referring to is the traverse of Grépon.

Her letters offer us fascinating details into the life and experiences of a female climber at the time. She certainly wasn't regarded as being in any way physically inferior by Mummery, in fact she was the one chosen by him to go on ahead with him and to 'get the step cutting done ready for the others when they had breakfasted'. Nor did Bristow lack faith in her abilities musing that 'I have often felt on climbs that if I had sufficient knowledge … I could have done it myself'.

Mummery's view was decades ahead of its time, his wife Mary - a skilled climber herself - would bitterly write about the prejudice she faced, stating that 'the masculine mind, however, is with rare exceptions, imbued with the idea that a woman is not a fit comrade for steep ice or precipitous rock … that she should be satisfied with looking through a telescope'. (Mary Petherick, My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus).

This climb of Bristow's up Grepon, however, proved rather more complex than anticipated, involving a 'succession of problems, each one of which was a ripping good climb in itself'. For Bristow personally, the fact that she was lugging a great plate camera with her up the mountain to try to make a record of their achievement did not help. She managed to take her images though, largely by using Mr Hastings' head against a rock as a makeshift tripod as the weather wouldn't allow for her to set up the proper one.

A fearless photographer, Mummery described how, whilst climbing, Bristow 'scorn(ed) the proffered rope. On (her) aerial perch we then proceeded to set up the camera, and the lady surrounded on three sides by nothing and blocked in front with the camera made ready to seize the moment when an unfortunate climber should be in his least elegant attitude and transfix him forever'.

That night they camped in the mountains and Bristow shocked everyone who heard an account of the expedition by sharing a tent with six others as an unmarried woman. Fred, 'pulled off (her) boots and wormed (her) into a wet sleeping bag'. They were six squashed into a tent that would have been a tight fit for three.

By Victorian standards no woman of respectability would have allowed herself to be put in such a compromising position, yet Bristow gleefully recounts it without a second thought, and it is impossible to escape the impression that she was justifiably proud of her physical strength and ability to cope with such conditions. These attributes flew in the face of Victorian thinking, whereby the female form was considered unsuitable for such physical exertions. Even when watching female gymnastics, spectators in 1867 were made to understand that they were watching a display of 'feminine grace' (24/12/1867 Morning Post Gymnastics for ladies), rather than any sort of display of physical strength or stamina. It was an attitude that Bristow, and other female climbers, despised.

Up in the tent that night, the wind - Bristow tells us - was 'rampageous', and the next day Bristow joined the men in 'crawling down the wet slippery rocks' in her masculine trousers, camera on her back. The only complaint she made was that her hands were very sore, otherwise she was 'perfectly fit', and she was already planning her next expedition, this time up Aiguille du Plan.

Mummery recorded that her 'smooth style on the Grepon, showed the representatives of the Alpine Club how steep rocks should be climbed'. By this stage, Fred was often letting her lead on their climbs, which Bristow writes she 'always enjoy(ed)', and she did so on their trip up Petit Dru. Even if Mummery had wished to turn back, his Victorian conscience would not have allowed him to leave Bristow if she refused, and in his book My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus there is a definite sense that at times he would have preferred a different course of action.

It is testament to the force of Bristow's character and expertise that, by this stage, where she led Mummery followed. They went guideless and Bristow found the climb 'pretty stiff, I must say, though not nearly as difficult as the Grepon, which is a real snorker'. At the top Bristow drank lemon and melted snow, enjoyed the view, and rested.

By this time Bristow and the Mummery's climbs were causing quite a stir and a 'great deal of enthusiasm. His having taken a lady up the two most difficult peaks here, without guides, in the course of one week and having sandwiched between these expeditions a totally new ascent of a very difficult peak is really worthy of some applause'. Unfortunately, it appears that only one or two of Bristow's pictures ended up being usable, but they do include one of Mummery precariously balanced on an ice face.

Nor were they done yet. On the 15th August 1893, Bristow records that Fred 'proposed that we should go up the Rothorn next day', and so, on very little sleep, they duly set off but soon encountered difficulties. Mummery declared they should turn back as they would not get to the top but Bristow, in her own words, 'begged and prayed in my most artful manner' and on they went, reaching the top by 10am. Bristow had carefully concealed from Mummery just how long it had taken them by juggling their watches and outright lying about the time when asked.

Bristow was thrilled and had only one complaint, that on the way back down her 'superior hat' and goggles had been knocked off by their rope and the resulting weather she said, somewhat tongue in cheek, 'ruined her cherished complexion'. The people at their hotel simply could not believe that they had surmounted Rothorn so easily, without even a guide, and declared it to be 'pas possible!' Still a difficult climb today, the locals suggested that Bristow and Mummery had mistaken Rothorn for an easier climb, but this was not the case. Bristow and Mummery's achievement is still considered remarkable today.

This was to be the pinnacle of Bristow's climbing career and upon her return there was a good deal of interest in their achievements. It has even been suggested by scholar Eliza Kay Sparks that Virginia Woolf's character in To the Lighthouse, Lily Briscoe, was named after her. Certainly Woolf would have been aware of her achievements, her father Leslie Stephen was a frequent visitor to the Alps, and a keen mountaineer himself. As one of the earliest presidents of the Alpine Club he would have seen and no doubt read accounts of Mummery's expeditions, and in them Bristow's achievements.

There now arose a rumour that Mere Mummery forbade her husband to go climbing with Bristow again, as she suspected a romantic entanglement on their part, but there is no evidence for this. Male commentators were keen to add a romantic twist to any woman's activities in the 1800's, in order to place them within a socially acceptable emotional framework. However, given the two women's respective characters, it seems more likely to have been an issue - if indeed such an issue existed - of professional jealousy.

Bristow's 1893 adventures were to prove her last major climbs. Her partnership with Mummery, whatever the reason, dwindled and she did not accompany him on his expedition to Nanga Parbat during which he died alongside his Gurkha guides in an avalanche whilst reconnoitring the Rakhiot face. Today we call it a lucky escape, but Bristow in all likelihood regretted the chance to attempt such an ambitious climb, even knowing the outcome.

All quotations are taken from the letters of Lily Bristow, which were written to her family and published in various magazines and newspapers, or from Mummery's 'My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus', his own account of their adventures.

- ARTICLE: The Pigeon Sisters 17 Feb, 2023

- ARTICLE: Trailblazing Mountaineering Women - Anne Lister and Ann Walker 19 May, 2022

Comments