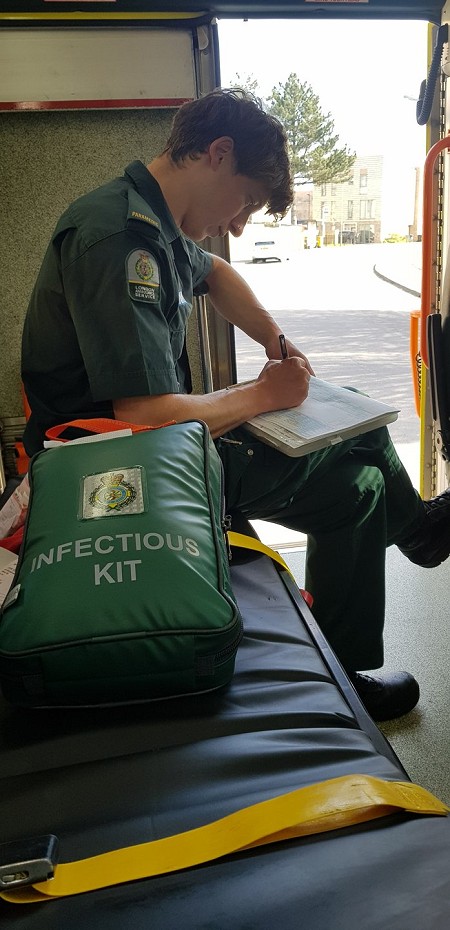

London Ambulance Service paramedic Jerome Mowat writes about shifting from a climbing trip to the front line as he joined thousands of his fellow NHS workers in the fight against COVID-19.

It's unusual to have an ambulance station mess room full of personnel. Normally once you start shift you don't return until the shift is over. There's no downtime and no breaks. So it was with some surprise that I found a dozen or so staff in homogenous green uniforms lounging around. 'All waiting for vehicle deep cleans', one of them said, as if the question was written on my face. Some of them had been waiting hours. It was February 14th, Valentine's day, the first Covid-19 death on these shores was still three weeks away. All cases were 'imports' and public health England was carrying out contact tracing.

Everything was slower back then. We had the luxury of time, with just a few dozen cases across the capital. These could be dealt with safely using the resources we had available. Ambulances were being deep cleaned after any potential COVID-19 patient was transported. Deep cleaning took 24hrs back then, which included a quarantine period.

I squeezed into the only remaining space on the sofa (social distancing wasn't a thing back then) and obsessively scrolled the news for information of this new threat, as we all were. A few hours later we received our ambulance from a finishing day crew. We passed a good but unremarkable shift: no one died and we finished on time. I discussed the situation with my crewmate as we de-kitted the ambulance. 'I'm sure it'll all blow over, the way SARS and MERS did,' my crewmate replied, not sounding fully convinced.

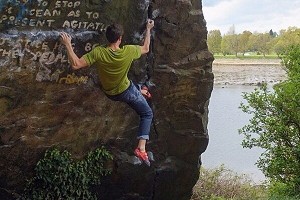

That was the last I thought of the novel coronavirus outbreak, for a few weeks at least. I sank into the familiar climbing trip routine: dropping all responsibilities, my only concerns being skin condition and which crag to climb at next. I was climbing at Oliana when the country went into lockdown. Together with all the international climbers I made a speedy departure for the border. The headlines back home were alarming. I climbed a few more days in Gorges du Tarn, but it felt increasingly unsavoury and indulgent. I couldn't watch from afar as a wave of suffering and death engulfed my hometown. Climbing is normally my solace, what I fill my thoughts with instead of dwelling on what I see on the road. I love how climbing is at once so meaningless and yet meaningful. But now was not the time for escapism.

Before the start of shift, my crewmate gave me a crash course in all that had changed in my month-long absence, which was just about everything. Low and behold, our first patient was a likely coronavirus patient. We donned plastic aprons and surgical masks in the back of the ambulance. The first few times it felt strange, but a few dozen times later I can say I'm pretty slick at tying knots behind my back.

It was a call out to a 65-year-old male; the same age as my father. For the past 10 days he'd been isolating since suffering a fever and cough. His symptoms had been worsening, to the extent that after speaking to the 111 urgent number, we'd been sent to triage him. He was sat cross-legged on the sofa, pale and clammy. My crewmate hooked him up to the monitor and I listened to his lungs. Where one would normally hear faint, reassuring breath sounds, there was a faint bubbling at the bases, like blowing into a straw in a glass of water. And nearer the top, the breath sounds were almost absent. His oxygen saturations were very low, and even with the highest dose of oxygen they were still dangerously low. My crewmate and I exchanged looks, as if to say 'How on earth is this guy still sat upright?'. These are normally the observations of someone 'peri-arrest', unconscious and approaching death. With a sense of urgency we assisted him on our chair and brought him to hospital. He was a 'blue call', where we pre-alert the hospital of the patient's details and vitals so they can prepare a bed and a team in the resus room.

It was my first encounter with an A&E prepared for a pandemic. One of the Majors wings had been sealed off and transformed into a makeshift ICU. We wheeled past transparent sliding doors containing rows upon rows of patients, all on ventilators or wearing CPAP masks. Something was different thought: they were all relatively young, in their 50s and 60s, not approaching the end of their life. We reached our bay and handed the patient over, telling the doctor a story she had probably heard many times that day already. Our patient would have assisted breathing imminently, and it was 50/50 whether he would survive*.

The LAS is currently at REAP 4 indicating extreme pressure on services. There is only one level higher - REAP 5 critical pressure - whereby demand dangerously outstrips supply and harm will come to the public. We've already pulled our motorbike and cycle responders onto ambulances, in some instances the fast response car paramedics are being paired with patient transport to man makeshift ambulances. These are unusual measures. Smaller satellite stations have been amalgamated with larger hub stations to make stocking and cleaning vehicles easier and to pool supplies. Our clinical managers are coming up with novel ways to increase resources and keep operations running smoothly.

Hospitals have found novel methods of dealing with contamination. All A&E departments now have 'dirty' and 'clean' areas, often separated by DIY barriers fashioned with plastic and tape. In the ambulances we've closed off the driving compartment from the saloon and employed a small army of deep cleaners. We've geared up for chemical warfare at double quick time. Hazmat suits used to be the reserve of our Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear (CBRN) specialists, but now the wearing of them has become routine. They're used on all cardiac arrests and any critical patients requiring airway interventions, because of the high concentration of viral particles in the air. This new norm has lead to hilarious scenes of pulling up on a street corner, grabbing the suits out of their packs and hastily pulling them over our boots and uniform, on the brink of toppling, as bystanders gaze in horror.

'You must be busy,' is something the public often ask us. The fact is, we're always busy, even before the pandemic. Ambulances in all cities, particularly London, have an operational rate of around 95%, which means we're either going to a call, attending to a patient or handing over at hospital. Once clear at hospital we go straight to the next. What has changed however is that the majority of patients we go to now are fairly unwell. No more children with moderate temperatures, no more earaches, no more hypochondriacs. Before we would go to a mix of elderly fallers, chronic and acute illness, substance and alcohol abuse, mental health, social issues, and a dash of traumatic injuries. These haven't gone away, but now we have a massive number of COVID-19 cases that require treatment or triaging. Call numbers are breaking records on a regular basis, like a busy New Year's Eve but every day. Both the 111 and 999 call centres are being battered.

We received a call to a care home for a 92-year-old male, not responding. The call was already three hours old, despite his category 2 status requiring a 20 minute response time. My crewmate flicked through his care records on the iPads we've all been issued with as I drove to the call. 'Do Not Resuscitate… should be treated at home by District Nurse team or GPs wherever possible…' we were walking into an ethical minefield. 'What you reckon, sepsis?' I tested him. 'Yeah, I reckon so.' This is a very typical call; the elderly picking up a chest or urine infection causing their weakened immune systems to enter a lethal feedback loop of destruction. Inflammation in their lungs and their bodies rapidly shutting down. But the pandemic is shifting the threshold of treatment uncomfortably far away.

We were led up the steps by the carer to the patient's room. His rapid, panting breath was audible from outside. Hooking him up to the monitor confirmed our suspicion: low oxygen saturations, a rapid heart rate, fever and all but unconscious. It was something that could be reversed with intravenous antibiotics, oxygen and fluids, but the prognosis was poor and there were no beds in nearby hospitals. Over the next hour we consulted with his family and the out of hours GP. It was decided: we would leave him at the care home, and a GP would come to make him comfortable with analgesia and sedatives. He would die in the near future, but he would die with dignity in his home, and not in a hospital corridor with no one familiar in his last moments.

Our last call of the night was to a man having chest pain with an extensive cardiac history. It sounded potentially serious. 'Ah, non-COVID, for a change,' my crewmate remarked. It was at a large train station in central London, which would normally still be bustling at this time but was now silent. We spotted our patient, standing at the entrance, shopping bags in hand and wearing a greasy trench coat, hallmarks of an NFA, or No Fixed Abode. We opened the door of the ambulance and my crewmate greeted him by his first name.

And then I understood: he was a regular, of which the ambulance service has many. He was heavily on the Spectrum and had a potent combination of mental health disorders rendering him quite vulnerable, as is often the case with regulars. These 'frequent flyers' are a tiny proportion of the patient demographic, but consume a disproportionate amount of our time. Everywhere has their own regulars, and knowing who they are and how to deal with them is as important as knowing the local hospital procedures. Still, I could barely contain my annoyance that in the middle of a pandemic, we were still going to them. We conveyed to a hospital south of the Thames and walked him into the A&E, where he was also greeted by his first name by the triage nurse. Back in the ambulance I expressed my irritation to my crewmate, but he was more philosophical about it. 'We still have a duty of care to these people, and they deserve kindness just like everyone else.'

'Even in a pandemic?' I asked. 'Especially in a pandemic.' He was a wiser man than me.

I'm full of praise for my colleagues in the London and Yorkshire ambulance services in this time of crisis. They, like much of the health service, have been forced to adapt to a new reality, the likes of which none of us have seen before. Over one thousand LAS staff are isolating or off sick with COVID-19. We're all resigned to the fact that we'll probably all catch it at some point, and terrified of being asymptomatic carriers and passing it on to the many vulnerable and elderly patients we see. This is why antibody testing is vital for all frontline staff. What helps is the overwhelming support from the public: children wave at us from windows; people come out from their houses with gifts and food.

There are many healthcare professionals in the climbing community: doctors, physios, nurses, paramedics. I salute all of them in these unprecedented times for going out there and getting it done. And the climbing community as a whole for taking responsibility for their actions, closing the gyms and prohibiting outdoor climbing. Sometimes these measures can feel quite abstract, are they really necessary? But I assure you, they are. This may be one of the few times we truly are all in this together.

Comments

Thanks for that

Brilliant piece, Jerome. I follow you on Instagram (as a climber!), but it's been eye-opening seeing your posts change to snapshots of your on-call life.

Thank you so much for what you are doing.

Great article, thank you

Thank you....a really excellent piece, humbling, gracious and so well written.

Full respect and gratitude to you and your colleagues.

I've read several broadly similar pieces recently, though none better written than this. Somehow, coming from a fellow climber, the message is even more stark and undeniable.

Thank you for sharing so vividly.