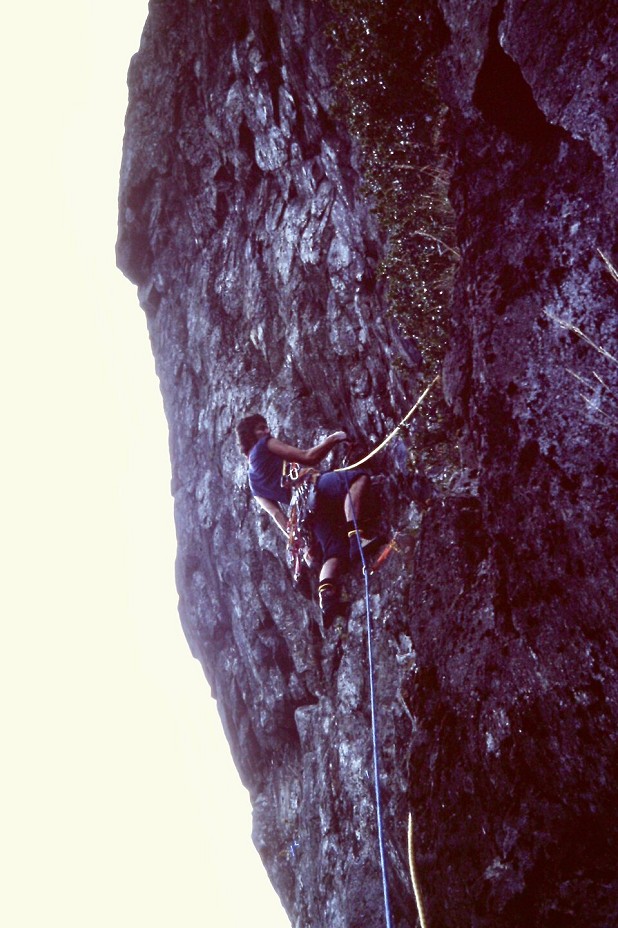

"These days we're bombarded by images of honed athletes powering up wildly overhanging rock and it's difficult to comprehend what it must have been like for Rob Matheson when he decided to attempt the imposing groove-line of Paladin at White Ghyll in the Lake District back in 1970.

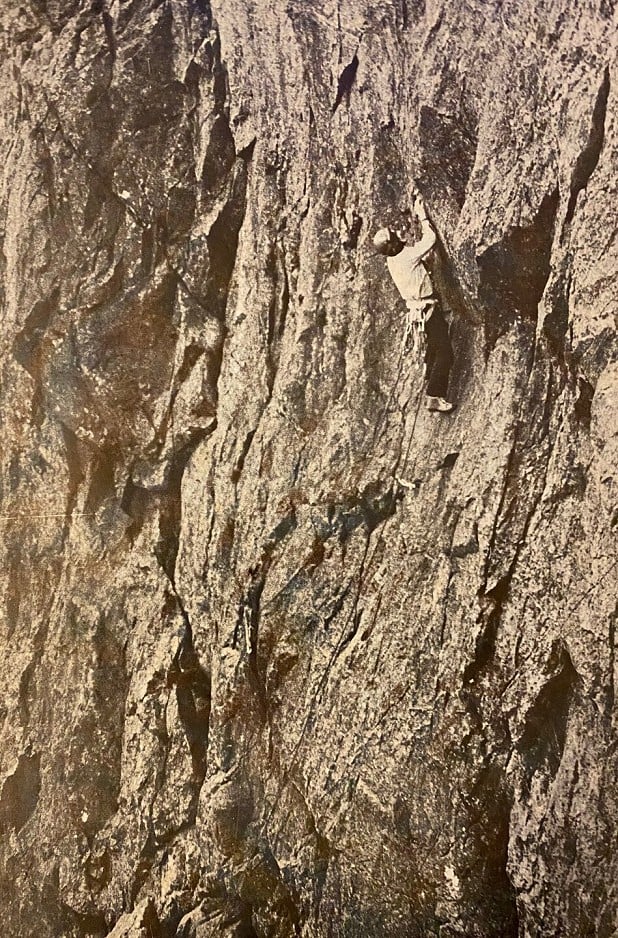

"For a start, there were no climbing gyms for refining your skills and training hadn't been conceived. There were no bolts, pre-practice was frowned upon and an onsight ethic prevailed. But most notably, trad protection in those days was a token gesture - a home-made nut tied-off with a piece of hemp-line wedged in a crack, and that's if you were lucky! It's no surprise that most of the routes at the time were slabs or vertical walls and an overhang like Paladin would have been considered incomprehensible. There are many strong climbers today who would still be intimidated by a route like Paladin, and rightly so. It really can't be conveyed in words just how 'out there' it would have been over half a century ago."

- Neil Gresham

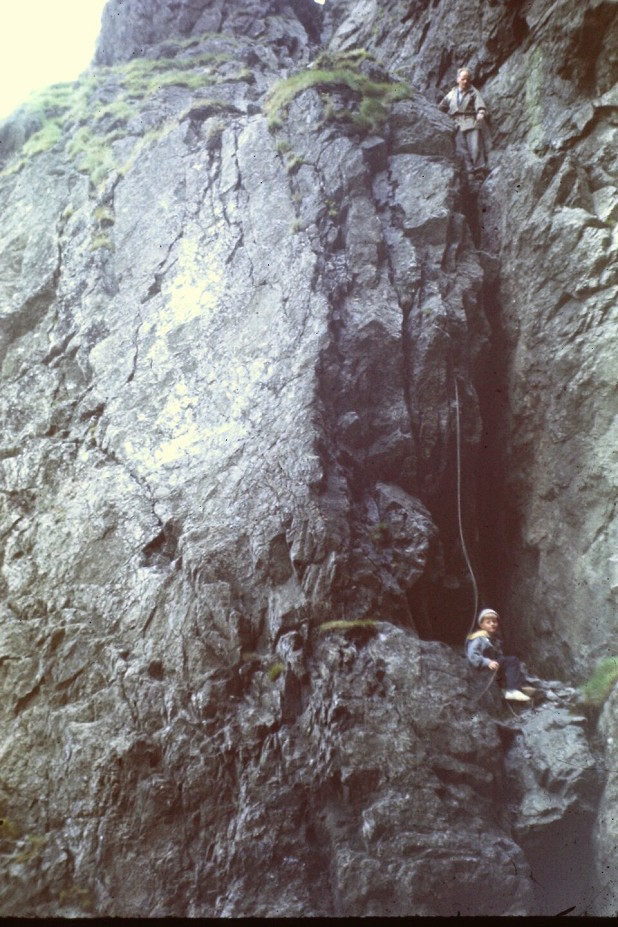

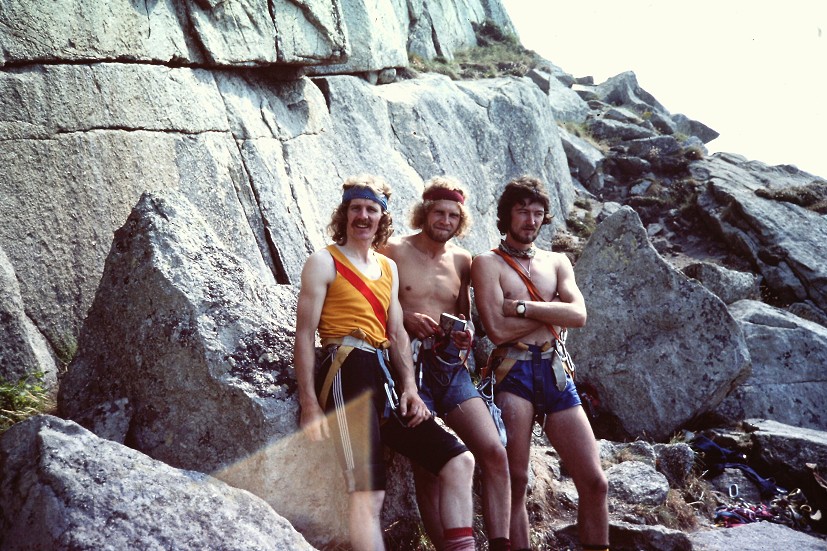

The Mathesons lived in Barrow and their regular walking—and later climbing—haunts were the Duddon Valley, Coniston and Langdale. 7-year-old Rob had his first mountaineering experience on The Cobbler in the mid-50s and for the following few years, the family began learning about rock climbing together.

"We spent many long weekends and evenings climbing as a family, Dad, Mum and myself, mainly on Wallowbarrow Crag in the Duddon, Scout and Raven Crag in Langdale and of course on the mighty Dow Crag above Coniston. Our equipment was basic, to say the least. We progressed from a borrowed hemp rope to a Viking 11mm nylon one, with some 9mm slings and a few Stubai and Cassin big D carabiners. Dad bought a few Moacs, which complimented our trusty collection of drilled out nuts. No harnesses — rope round the waist with the bowline knot. No belay plate — just behind your back with a twist round the bottom arm!"

Early on in Rob's climbing escapades, his parents began chatting to a climber who was making light work of everything at Shepherd's Crag in Borrowdale. After soloing everything in sight, Rob followed him up Monolith Crack (VS), which he describes as "a great leap forward in grade for me at the time."

"He told me to get some proper climbing boots so you could stand on nothin'."

The man introduced himself as Ray McHaffie and inspired Rob to not only buy his first pair of rock boots, but lead his first VS a year later.

There was little awareness of what the wider climbing world was up to in Rob's early days. Cragging with his parents wasn't insular as such, but the climbing took precedence:

"There was no holding us back and the rest of the climbing world was irrelevant."

Moving up the grades had been slow; a V.Diff to Severe was a major event, but the ticks in the family guidebook were racking up. Ground-up and on sight were their only methods of climbing and by today's standards they were weak, but Rob attributes their success to "crag-craft and mental resilience."

It wasn't until his late teens when Rob started to become aware of what other climbers were doing. There weren't many places to hear about climbing news and Rob's information all came from the dominant Fell and Rock Guidebooks, or other 'pirate publications.' His focus was on finding new climbs to tick off and by his own admission, he 'wasn't really into the history of climbing' at this point.

The Lakes scene in the '60s and '70s was insular, even territorial. Climbers focused on their own patch and were wary of outsiders coming in and pinching lines, which did happen; Geoff Oliver climbed the classic Ichabod (now E2 5c) on the East Buttress of Scafell, Pete Crew added Central Pillar (E2 5c) on Esk Buttress and Les Brown was adding hard, committing climbs across the Lake District, to name a few.

By the late '60s, Rob had completed most of the hard routes in the Lake District, climbing them as per the guidebook description at the time.

"If there was an aid point it was not in my psyche at the time to try and dispense with it. I was just happy to tick off the routes."

Now an experienced climber with a number of hard repeats to his name, Rob was beginning to look for new challenges and a line at White Ghyll caught his eye:

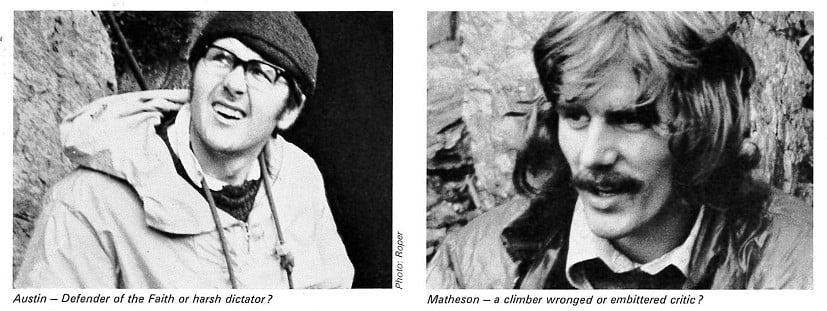

After Rob's ascent of Paladin, the Lakeland establishment began arguing against his tactics. Allan Austin was particularly critical that he returned to free the route after climbing it on aid. When repeating it, Austin used two points of aid, casting doubts on Rob's claim and in the 1973 guide wrote the route up with his two points of aid.

'This hurt at the time, so climbing it again 50 years later meant a lot to me - job done!'

Over the next couple of years, Rob, together with Pete Livesey were very active new-routing in the Langdale area but occasionally used pre-placed gear, sparking further debate, particularly relating to aid slings left in place. Pre-placed gear and pre-inspection are par for the course in the modern era, but the Lakeland hierarchy—in the form of the Fell and Rock Club—at the time were in stern opposition to such techniques.

"I do not see crags as impressive backcloths where ruthless men can construct their climbs.'

Allan Austin

Their strict ethos was a determination to 'preserve the true spirit of rock climbing.' This determination led Austin and Valentine to omit Rob and Pete Livesey's routes from the 1973 Langdale guide, despite Rob's honesty on the tactics used. Rob had spent the early '70s climbing new routes; Paladin, Cruel Sister, and Holocaust to name a few. On Cruel Sister, Rob made use of a skyhook to reach an in-situ sling on a peg. His aim was to tackle the overhanging section directly; he didn't think of bypassing this section and traversing in, something that the first free ascent did. To quote Rob, 'I'd bought a skyhook and I was going to use it! But hell let loose, anyway' at the FRCC.

Writing in to Mountain magazine, Rob accused Austin and Valentine of omitting 'harder new routes, which the writers either hadn't done or couldn't do, or which they considered used too much aid.'

Allan Austin's retort in the following month's issue included the fantastic line: 'I do not see crags as impressive backcloths where ruthless men can construct their climbs.'

Austin's argument was that by using tactics such as pre-placing gear, climbers made their ascents certain and this went against the challenge of difficult rock climbing.

The ongoing debate into what constituted fair practice on first ascents was part of an ongoing wide debate in the British climbing scene; were pre-placed runners allowed? What about abseil inspection? Points of aid? The lively exchanges in Mountain magazine appear hypocritical, mostly on Austin's side of the argument. He didn't appear to have a clear policy for what made the cut in the guide. Climbing was unquestionably in a teething phase at this point; free climbing was not yet de rigueur and what perhaps matters most is that Rob was honest in his descriptions.

Ethical dilemmas in the Lakes cropped up frequently over the next decade as the sport settled. Climbers like Pete Livesey were making their mark across the UK with ascents of Right Wall (E5) and Footless Crow (E5). For Rob, the focus was pushing towards the mythical E5 6b barrier. Ethics were becoming more set in stone for the new Matheson/Cleasby team:

'From our perspective, we often abseiled and cleaned the lines but there was no top-roping or pre-placing gear, not even pegs!'

Gear was occasionally slumped on but was declared as aid, such as on Shere Khan (E4 6a) and Mother Courage (E3 5c). But once on Deer Bield Crag in an effort to get Imagination (E4 6a) done before the end of the day, Ed Cleasby did top-rope up to check the crucial gear before leading it. - 70s grades - graded at the time

'Well, strong words certainly flowed in our direction when Pete Whillance found out about the top-rope, as this had not only been one of his favoured lines, but in his opinion top-roping was cheating and totally out of order! A couple of weeks later Ed put up a new route in White Ghyll called Ethics of War! Ah well, all I can say is that Pete Whillance carried such respect, that his opinion was not there to be ignored! I do not recall top-roping again in this era!'

Towards the end of the decade, Rob's motivation for climbing was waning. He'd lost some of his obsession and by the early '80s he'd given up entirely. Mad potholing, windsurfing and squash took precedence. Climbing had undergone a bit of a revolution in the '80s and when Rob returned in the '90s, he was shocked by the standard.

Hooking up regularly with the 'Barrow Boys,' he sampled indoor walls for the first time, getting burnt-off by a young crimper called Dave Birkett. The Boys travelled up and down the country, onsighting E5s and practising a few harder ones. Rob soloed Slip and Slide (E6) at Crookrise, led Linden (E6) at Curbar and ticked off some classics like The Cad (E6) at Gogarth. It was around this time that Rob's eldest son, Craig, had dipped his toe in the water and climbed his first route – a severe at Pot Scar.

"It's popular to suggest that age isn't a barrier in climbing but I think there are some obvious challenges for older climbers to overcome. I find it incredibly inspiring the way Rob has kept pushing forward. It takes skill and wisdom to avoid injury, and motivation can start to dwindle, especially when we notice that most of our partners are half our age! It's clearly not going to happen unless you have a deep love of climbing and there's no doubt that this is the fuel that powers the Rob Matheson machine!"

"In modern climbing, strength seems to be the most valued commodity and we're often told that we need to be able to do certain things on a fingerboard in order to climb hard. Yet climbers like Rob Matheson prove to the contrary by re-writing the training books and reminding us all that in fact, nerve and skill are at the centre of things."

- Neil Gresham

Rob set himself free in 2010 and retired from teaching. His aim: get strong. Injury struck nearly straight away and he learnt important lessons about addressing muscle imbalances and starting to take care of himself. He returned to climbs that had haunted him in the past. One, in particular, was Cave Route Right Hand (E6) at Gordale:

'I was totally disillusioned at being so far behind the leading pack and could never hope to climb anything like that. Shortly after, I gave up climbing completely. So, at the grand old age of 61, I returned and led it.'

After his retirement, Rob and his son Craig began climbing together more. Craig's skillset and strength had improved greatly since his lead at Pot Scar and his climbing CV is now bursting at the seams. He's climbed first ascents of outrageous E8s like Stopper Knot at White Ghyll, repeated Birkett's routes Another Lonely Day (E8 6c), If 6 was 9 (E9 6c), and perhaps the hardest of them all - Welcome to the Cruel World (E9 7a).

A serious broken finger at the end of 2014 put paid to Rob's climbing efforts, so he took up cycling, as many climbers have done. Not for pleasure in this case but for serious competitive road racing, involving four years of intense training. Physically and emotionally he 'hit the wall' in 2018 after clocking up several wins and many podiums on the journey. Craig, for one, was glad to get his dad back into the climbing fold. Although they obviously climb several grades apart, their love of the mountain crag environment shines through.

"Personally, as I move into my 70s, I want to continue my 8-week blocks of 'steady state' training, as this is keeping me injury free, and enables me to work on my weakest muscle groups. This also involves working on that creeping stiffness in those joints and hip flexors - this has honestly helped massively! Recently I've had long discussions with Neil Gresham about training my weaknesses, which has been really useful in developing strategies, no matter what age, or grade you are aspiring to.

"Motivation is another force which I constantly have to work on. It's all very well having a wish list or desire, but the real test is getting off your backside, often when it doesn't particularly suit, and taking a positive move in the direction of your goal, which may well be to walk up to Scafell in the pouring rain and abseil down that new line you have often thought about. The advantage of having climbed for so long is that some of my early first ascents, such as Paladin, Cruel Sister and Holocaust are up for 50-year anniversary ascents which are, of course, purely personal. This is likely to get more challenging as the years progress and grades increase! And an E7 at 70 seems poetic!

"As I get older it seems even more important to maintain that drive and focus, and do what you can to stem that southerly flow."

- Rob Matheson

Below is the video of Rob's first ascent of Scarface (now E6 6a) on Cam Crag in Wasdale:

Comments

That was absolutely amazing.

I've met Rob a few times over the years and have been star-struck each time, not least because of what he's done, but also because of what he's still doing - it's inspirational on all levels (and also a bit mind-blowing).

Great article too Nick. It's definitely got me psyched to repeat some of his routes as/when we're allowed to travel again. That said, I'm going to have to put some time into training for them, because not many of them are easy!!

I've had this same feeling very strongly once - while leading the top pitch of Vulture at Cilan. 1968... proper E4, and WAY out there. Jack Street, what a legend.

Perhaps the mid-career climbing break is no bad thing g as you return more hungry. Great article. I seem to recall climbing with one of Robs's mates (Stuart) when I was doing my ML in 1974. Seems a lifetime away.

Brilliant article and videos. Really enjoyed Rob's walkthrough of Paladin. By the by, IIRC, both Central Buttress and Tophet Wall were subject to abseil inspection. Some people's ethics were based mostly on mythology.... ;)

Totally agree. I think Central Buttress was subject to more than abseil inspection! There's an argument for regarding it as the first (or an early) worked project/headpoint. I guess that Austin & co viewed it simply as an historial anomaly rather than a different way of doing things.

It's probably hard (or impossible?) for people now to appreciate just how powerful an influence the mountainering ethos once had on rock climbing. (By 1970 it had been around for about a century.) With this ethos, of course you start at the bottom and end up at the top. However once you abandon the ethos, you can pretty much do what you like as long as a) you don't damage the rock and b) you don't lie about stuff.

At the time I had considerable sympathy with those on both sides of the divide. But the conflict was handled poorly - as it would be, a decade later, with the bolt wars. In particular, I feel that the treatment meted out to Rob Matheson was downright unfair. It's probably rare for such stories to have happy endings and I'm glad that this one does. That he's climbing so well, 50 years later, is testament to a lot of talent, a lot of motivation and a lot of hard work. Long may it continue!

Mick