Graham Hoey remembers friend and gritstone legend John Allen, who died earlier this month in a climbing accident in the Peak.

John Allen 10th October 1958 - 18th May 2020

On Monday 18 May 2020 John Allen tragically lost his life in a fall at Stoney West. He was a well-loved legend within the climbing world and well on his way to becoming a National Treasure - a title which would have amused him but one I feel he would have accepted with his usual humility.

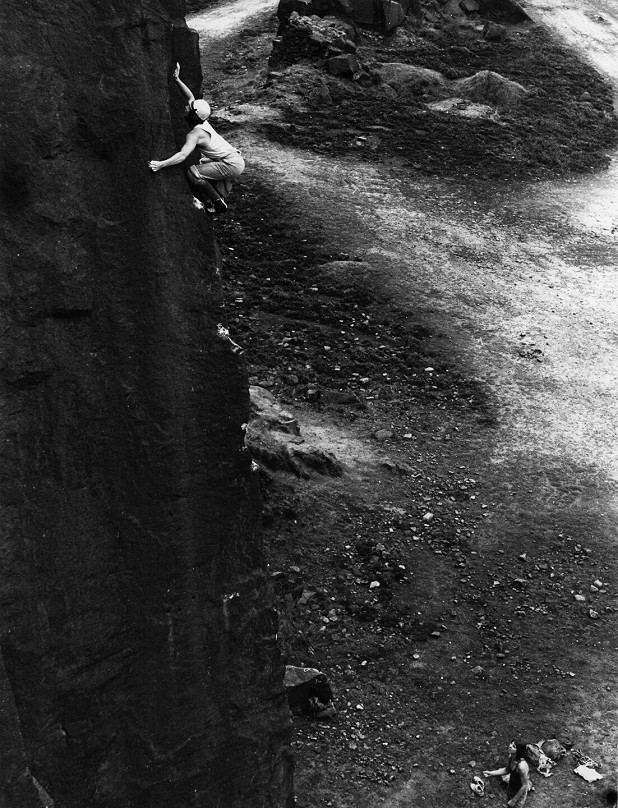

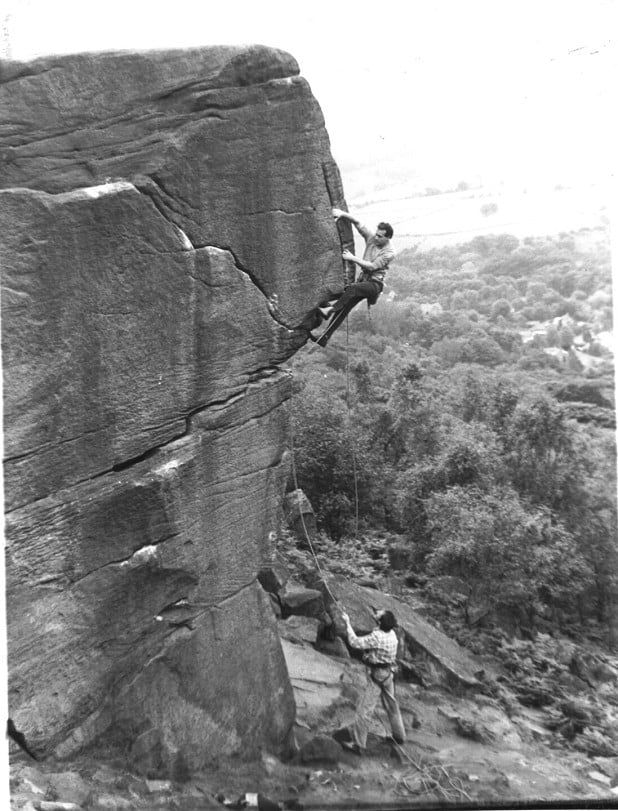

John started climbing around the age of 10, being mentored by family friend and experienced gritstoner Les Gillott. On their early forays from his home in Sheffield, John would imagine he was his hero Joe Brown and when he was just 12 years old he led what was arguably Brown's hardest gritstone route, the Dangler (E2 5c) at Stanage. A year later he was adding his own routes and went one step further than his hero by leading Soyuz (E2 5c) at Curbar Edge, a line attempted by Brown some twenty years before. These were pre-Ondra days when climbers didn't step out of nappies onto a climbing wall and for a schoolboy to be working his way through the hardest gritstone climbs of the day was simply unprecedented. Then, in 1973, Allen stunned the local climbing fraternity with his ascent of the 'impossible' east wall of High Neb Buttress at Stanage Edge. Old Friends (E4 5c) was a serious route with poor protection and a strenuous, technical, committing crux an uncomfortable distance above the ground. Along with his equally demanding climbs, Constipation (E4 6a) and Stanleyville (E4 5c) also done that year, Allen had added three of the hardest routes on gritstone at the age of just 14. Only Green Death (E5 5c), Edge Lane (E5 5c) and Linden (E5 6a (aid)) were harder. The following year, Allen demonstrated his increasing maturity as a climber by making the first free ascent of The Moon (E3 5c, 5b) on Gogarth. He was clearly no mere crag rat and more and more climbers began to take notice.

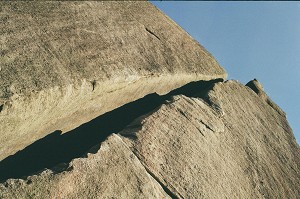

But the best was yet to come as the 'Shirley Temple of British rock' (as Crags Magazine dubbed him) went on to set gritstone alight over the next two years. His best routes from this period are amongst the finest outcrop climbs in the country and took gritstone climbing to new levels. In 1975 he added (amongst others) Moon Crack (E5 6b), Reticent Mass Murderer (E5 6b), Hairless Heart (E5 5c), White Wand (E5/6 6a), Profit of Doom (E4 6b), and London Wall (E5 6b), the last four of these being climbed within a two week period!

London Wall ...

at 16...

Unbelievable!

He also found time to pop across to Cloggy to make the (credited) first free ascent of Great Wall (E4 6a, 6a), although, as Mountain magazine laughingly qualified, his ascent did use chalk!

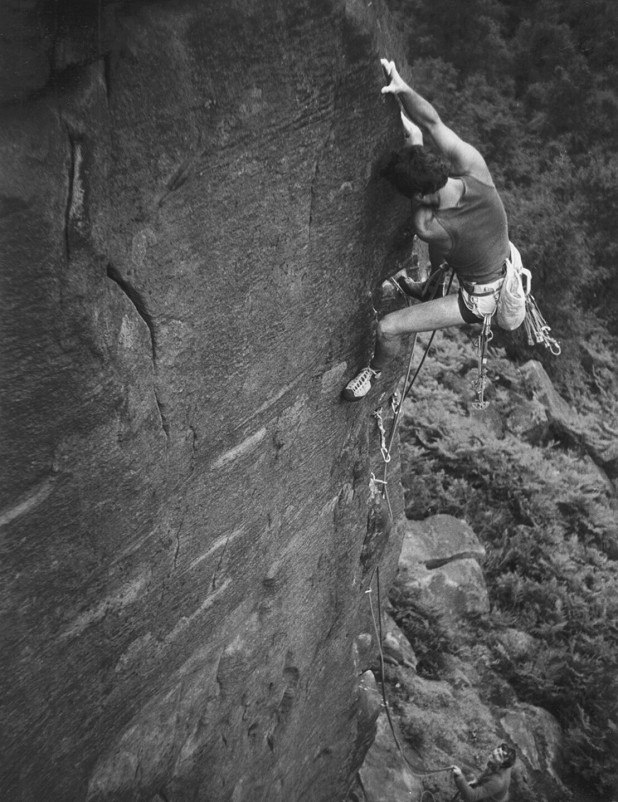

In 1976 the assault continued; Artless (E5 6b), Moon Walk (E4 6a), Nectar (E5 6b, 6b), Strapadictomy (E5 6a) and Caricature (E5 6a) - all simply stunning climbs. Of Caricature it was written that "Allen stepped over the threshold of the possible" and in a way this summarised John's attitude to climbing which made him and other pioneers before and after him so visionary. He was completely unfazed by the apparent difficulty of a line, nor by any reputation it may have acquired from the efforts of earlier 'greats' or his older rivals. He revelled in the challenge they represented at the time. Even today with cams, sticky boots and 'modern fitness' these routes from 1975-1976 still present a considerable challenge and on-sight ascents are rare.

Then, late in 1976 John left with his parents for New Zealand. First ascents here and impressive repeats of hard routes at Arapiles in Australia kept John ticking along. During this period he also proved his worth on big walls with a phenomenal (non-jumared) ascent in 1981 of The Nose on El Capitan with Simon Horrox in a day. Between them they lead and seconded every pitch; the first time this had ever been achieved, the locals were amazed.

In the early eighties John developed a recurrent dislocating shoulder which was so lax it could pop out when he rolled over in bed awkwardly. He eventually had surgery on it early in 1982. The recovery from this was quite slow, especially as the surgeon didn't believe in physiotherapy! He had difficulty trying to regain flexibility, but typically he didn't make a fuss about it despite it affecting his climbing for a number of years. After surgery, John returned to England to find that things had moved on somewhat.

Beau Geste had been climbed by Jonny Woodward and the grades were increasing. He found it hard to catch up. E7 was the new top level and the heir apparent Johnny Dawes was about to push standards even higher. Nevertheless, John carried on new-routing, adding a plethora of routes all over the Peak. Although no longer at the cutting edge, he was actually climbing technically at his best during the mid-eighties and produced some superb climbs including Chip Shop Brawl (E5 6c), West Side Story (E4 7a), Shirley's Shining Temple (E5 7a), The Fall (E6 6b), Boys Will Be Boys (E7 6c), The Children's House (E6 7a), Feet Neet (E5 6c) and Concept of Kinky (E6 6c - his last hard route on grit, in 1989). Some of these have become classic highballs whereas the others have yet to receive even a handful of repeats. Boys Will Be Boys is modern hard while The Children's House has in my view one of the finest technical sequences on grit.

Eventually John's business commitments and, it has to be said, increasing girth, led to a slowing down of his climbing activity, but he never lost the bug. Along with most of us he came to embrace sport climbing and regularly holidayed in Spain. More recently he had become enamoured once again with new routing and had been enthusiastically developing a number of sport climbs on the limestone quarries in the Peak District. This was not without excitement, however. On one occasion, to avoid being caught trespassing by the local farmer, John quickly threw himself to the ground and lay as flat and as still as possible in the long grass just metres away!

As a young grit-obsessed teenager climbing in the early 1970s I had heard of John Allen, "the next Joe Brown", but it wasn't until 1975 on Millstone Edge that our paths crossed. A young man walked up to Edge Lane, put on his helmet, tied on to his rope and promptly soloed it. It was a captivating sight as the climber calmly and smoothly made his way up one of the hardest routes in the Peak - I had never seen anything like it. "That's John Allen" my friend said. Allen was just 16, unbelievably a few months younger than myself, but looked considerably older with his strong physique and confident climbing style.

On his return from New Zealand in 1982 I got to know him through our shared love of gritstone climbing. We were kindred spirits, both 'children of grit' who had learned the subtle nuances of gritstone climbing and we both loved talking about it! On one occasion we came across each other in Chee Dale and spent ages discussing in minute detail the holds and sequences of some routes we had done on Stanage. After some considerable time John's climbing partner, Mark Stokes looked at us despairingly "Oh come on, that's enough 'Pockets and Pebbles' for today!" he said.

John had a wonderful, calm temperament and would always treat you as an equal, whereas I always saw him on a higher pedestal than myself, feeling the warmth and joy you get when talking to someone who is a master of that which you are passionate about. He was always a pleasure to climb with, wonderful to watch with superb balance and technique. I remember doing a first ascent with him on Rivelin Edge. I was going well on the grit, managing 6c (English!) pretty consistently. He was not in the best physical condition, but casually stepped up to a break, rocked into it using a pebble and stood up. Looks OK I thought, standard grit move, but it was only when I got on it I realised the sheer steepness of the face. On a slab I might have managed it but … I needed a bit of tight on that one!

John also had a fantastic sense of humour and a mischievous streak. We were once climbing on Ramshaw Rocks with the gritstone jedi Martin Veale. Coming up as third man on John's new route, I was astonished to find my car keys buried at the back of a break. It was obvious how they must have got there but when I accused John his absolute denial along with a completely deadpan face was so convincing that I was left flummoxed. It was over 30 years later that he admitted, amongst fits of laughter, that he'd put them there - still found it funny even then - lovely man. However, despite his mild nature and patience John didn't suffer fools gladly, which meant most American climbers he met in Yosemite! On one visit to the USA he fashioned a pair of aerials from coat hangers, attached them to his head and wandered into a local bar. Eventually someone was 'hooked' and asked him what they were for. "Communication with Aliens" he said matter of factly. Most people would have got a punch, but John had the charisma to get away with it.

He became in the course of his life a rich man, but no one would ever have known it to see him out and about or to hear him talking; John was never 'flash', he was always a warmhearted, generous man. He was also very modest about his achievements but he was understandably quite proud of them; when interviewing him for Peak Rock he jokingly said he rather hoped one day to see a chapter in a book entitled 'The John Allen Years'!

I regret I was not in the traditional sense a closer friend of John's. We would bump into each other at parties, at guidebook launches, out at the crag or go climbing together occasionally but we had a strong bond and respect for each other born from our love of climbing on gritstone. I will never forget his smile, his soft, lazy Sheffield twang, his childish mischievousness, his grace, poise and strength. I will miss the "Pockets and Pebbles" greatly. He leaves behind a fine legacy of climbs; "So Many Classics, So Little Time" (E4 6b John Allen 1984).

I will think of him as I solo along Stanage on warm summer evenings with the rising sound of the curlew behind and he will be there. No longer an old man but the young man I watched all those years ago floating effortlessly up a gritstone arête.

- DESTINATION GUIDE: Leonidio Limestone 9 Mar, 2017

- GUEST EDITORIAL: A Gritstone Retrospective 18 Feb, 2009

Comments

Many thanks to Duncan Critchley, Phil Kelly, Keith Sharples, Nick Taylor, John Codling, John Woodhouse and Alan Hoey

Great article, great photos, thanks very much

RIP John Allen

Nice read, thank you. For a flavour of John Allen's achievements take a look at this ticklist Paul from UKC pulled from the database - https://www.ukclimbing.com/logbook/set.php?id=4080 - stunning list.

A beautiful eulogy Graham, thanks for sharing.

Really enjoyed reading that, thank you