A reflection on the mishaps and close shaves of one climber's life...

Complex simplicity: Going Solo

I pulled the bike off the road, killed the rumble of the single cylinder motor and swung my leg off the seat. The void of silence was replaced with the familiar clicking and pinging of the cooling engine as it caught the gentle coastal breeze.

I lifted the open-faced helmet off my head, spat the insect debris from between my teeth and checked my face for bug splat in the bike's mirror. It's hard not to ride with a big, fly-catching grin on your face when you're trying to find the outer limits of the tyres on these twisty Cornish B-roads and, despite the tell-tale signs of age in the form of grey flecks in my beard and my thinning hairline, it still brings the same juvenile joy I felt when my ten-year-old self first twisted a motorcycle throttle.

The simple pleasures of motorcycling, combined with climbing, have been a constant throughout my life and still deliver the same thrill—even if the bike has been sidelined a little in my obsession to climb. However, on days when I am taken to seek isolation and total freedom, it provides additional depth of pleasure to a day's soloing.

I threw the helmet and jacket into the backpack, double checked I had packed rock shoes and a chalk bag and set off across the fields towards the coast path, drawn by the ever-present noise and turbulence of the Atlantic Ocean as it went about nature's work.

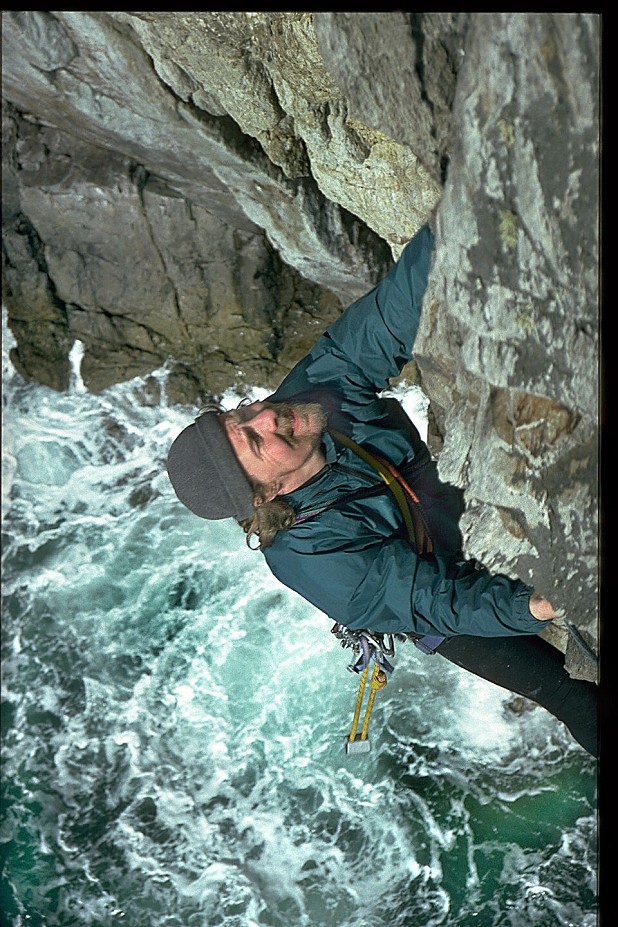

Passing under the giant white radar dishes and skirting around the double perimeter fence on the way to Lower Sharpnose Point is always a surreal experience. It feels like a scene from a sci-fi movie, which seems a little out of place when surrounded by such rugged natural beauty. Once the spy dishes are behind you, you can embrace the setting and take in some of the most stunning scenery that North Cornwall has to offer. Looking north on a clear day, you can feel the magnetic pull of the spectacular Lundy Island with its miles of granite and dream of its hidden zawns offering adventures to match any.

As I break off the coast path heading down towards the crag, the roar of the ocean intensifies. I push through the waist-high gorse and I am treated to a prick of its sharp thorns through my trousers but, almost as if in apology for its harshness, the sting is softened by the sweet coconut scent given off by its vibrant yellow flowers.

Looking down on the crag from above, I gulp in the updraft from the sea and feel the usual excitement as I view the steep vertical sandstone walls and contemplate the movement and exposure of soloing in such an uncompromising setting. I am startled out of my trance as a family of Peregrines screech past, twisting, stooping and playing in the updraft while giving their young fledglings a lesson in survival. How can such a sight taken as a whole not raise your spirits and swell your soul?

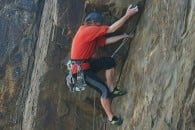

I like to spend time settling into a situation when I am out soloing; relaxing, breathing in the atmosphere, starting to feel at one with the environment. I like to take my time, to contemplate, to slow my heart rate down with breathing and prepare myself for smooth, unrushed, precise movement so I can feel the joy and unrestricted flow—no ropes, no gear, no weight…simple pleasure.

Shoes and chalk bag on, a few deep breaths...I pull gently onto the wall. The joy of soloing lies in its freedom, its untethered movement. It requires total focus and commitment. No room for error or uncertainty. Its beauty is a complex simplicity, simple in theory but deeper in its undertaking. It requires you to really know yourself, to be at one with your inner thoughts and your ability to stay calm and focused, to keep bringing things back to the positive if they should drift and the ability to shut out or deny the negatives so you can perform and survive.

I warm up on the crag's classic Extreme. The start is steep but positive despite the holds feeling damp and greasy from the last high tide. The line follows a 30 metre diagonal crack with a sting in the tail, but lives up to its name and always makes me 'Smile'.

After three or four routes I feel sated and I sit atop the narrow summit fin contemplating the thundering waves as the incoming tide cuts off the escape route from the zawn.

As I relax, I am taken by the fulfilling glow which always follows a flurry of climbing action in such committing situations. My mind drifts off on the breeze and contemplates what I find so attractive about the whole game.

To say when soloing that you can always be in control would be misleading—unless you are climbing well within your limit. If you get drawn into the headspace of pushing yourself physically, it is natural that psychological baggage will surface and it is certain that you will be sailing close to the wind. The art is to find the simmer point and not let things boil over. If you are seriously searching for that inner buzz, you will inevitably end up finding that edge and, surprisingly, it is often not at your physical limit.

Soloing is not something you can encourage in others and, although many climbers will taste its delights, it is not for everyone; it is a very personal inner game—not a game of chance, but a game of both mental and physical control. Often when soloing, you find cruxes are not in the same place as when you are climbing roped up. You can't take anything for granted and it always requires you to stay sharp and ready to adapt.

For me, the act of soloing with its commitment and simplicity fits with my ideals. I have gone through the same steep learning curve in life that we all face, but my aim has to been to keep things simple, uncluttered. To live the life that I want. I have often lived on fumes so that I can climb—being unmotivated by financial gain or possessions—and moved to areas that feed both my soul and my objectives. I can't say it has not been a selfish journey or one without casualties, but my biggest fear has always been the mundane; to live a life in beige.

During negative phases of my life, soloing has served as a means of sharpening the spirit, for resetting the way forward. Its intensity brings clarity and focus in a meditative way. It lays the cards on the table; there is nothing like the feeling that you have something to lose to make you realise that you have something worth saving! At other times, it has served my desire to be alone in a simple 'at one with nature' kind of way and, if I'm honest, I can't say that playing with fear doesn't have a hand in it.

For a few years, I went through a period when in the process of searching to extend the personal journey by climbing bigger and harder objectives alone, I got totally embroiled in the art of roped soloing with a 'silent partner'. I tramped around Europe in search of big walls to climb but, while I enjoyed the process and its challenges, in truth it is a full-on game which requires lots of effort and gear. It can be an intense and exhausting process demanding total focus and your full attention. It is not without its merits, but it is a million miles away from the freedom, joy and simplicity that is so attractive about free soloing.

As I ponder, my thoughts wander back to my introduction to climbing. It is amazing that I got drawn into it in the first place. My introduction was less than positive and if my early life had not been spent looking for risks and sticking my neck out, I may well not have got off the starting blocks.

Climbing back then, pre-climbing wall, was not as accessible as it is today. It was a chance meeting while working as a tree surgeon in the mid '80s that I met an addicted climber; a rare character who held an 'off the beaten track' view of the world in general. I say 'oddball' in the nicest way—we really meshed.

He would turn up for work in his Mk1 VW Beetle, which was hand-painted red and wax-oiled to within an inch of its life. His packed lunches looked like something from Peter Rabbit's larder, consisting of raw veg including carrots, radish, celery, garlic cloves and whole onions that he would eat like apples and stink out the cab of the wagon—much to his amusement and everyone else's annoyance.

His parents christened him Malcolm but I later found out his friends had given him the nickname ALF (which stood for Animal Liberation Front) after he had got himself a job in the local abattoir in order to uncover and expose animal cruelty, which ended up splashed all over the front pages of the local newspaper.

Our planned first weekend of climbing was foiled when I got an out-of-the-blue phone call from his partner to say he would not be able to make it. Alf was lying in bed in Buxton hospital after a 40 foot fall whilst soloing. He had attempted to make a deep crater at the base of Ruby Tuesday, an E2 at The Roaches.

Having spoken to him later about the incident, he explained in a matter of fact way that he was part way through the crux when he realised that he had nothing left in the tank. He had to make a split second decision whether to keep pushing and chance falling off out of control into the many boulders littering the base (which I'm sure would have been fatal) or choose his spot and jump hoping that he could land between them and perhaps minimise the damage.

He chose to jump; a decision that ended in a totally shattered ankle joint and a broken arm. Thankfully, Alf survived.

My introduction to climbing included the pitfalls, consequences and aftermath of what happens when you screw up while soloing. To say Alf was lucky is an understatement and after a long rehab we formed a partnership and climbed together for many years, despite his fused foot requiring modifications to his climbing style.

I'm not sure whether it was inspiration or stupidity that found me soloing the roof of The Wombat, an E2 only a few routes across from where Alf had impacted, but it just shows that you can't (or don't) learn from other people's mistakes. The practice of soloing had gotten under my skin from early on.

Soloing is a game of risk with little or no margin for error, but those close shaves come in some strange forms. Over the years my soloing has been peppered with a few spicy moments. All have left lasting impressions and taught me to never take anything for granted. I have learned to always be on my guard for a multitude of possibilities and pitfalls, which have rarely been down to lack of preparation. On numerous occasions, I have literally found my life in the balance when startled out of focus by an unforeseen incident.

Stockinged Feet!

This first incident was a real leveller and just goes to show that respect for the situation and the implications of gravity should not be purely based on grade. A week after an ascent of Right Wall (E5) on the open book walls of Dinas Cromlech in Snowdonia, I came very close to screwing up whilst soloing a steep and exposed Grade 3 scramble on the opposite side of the Pass in less than ideal conditions.

I can still feel the fear and vulnerability of my predicament. Steep, green, polished rock running with water in big mountain boots while carrying a heavy rucksack is not a good mix and the day was only saved by the removal of my boots and a precarious, wide bridging move across the waterfall in my socks to gain friction while trying to ignore the growling rocks gnashing their teeth far below.

Always expect the unexpected

I remember cruising around on Staffordshire gritstone at what was then my local crag of The Roaches and being hit in the face by a startled Tawny Owl. How it didn't knock me off is a miracle and it was only by instinct and fast reactions that I managed to hang on by the skin of my teeth!

The wood ants at Lawrencefield are notorious, they hide in wait on the ledges and belays to inflict pain on the unsuspected climber who sits on their underground labyrinths. One day while soloing in the quarry, I reached up to mantel onto a ledge to be met with an army who drew weapons and sprayed me in both eyes with formic acid! I hung there blind for some time while my eyes worked overtime to water away the sting.

Another memorable incident happened on East Germany's Elbsandstein towers while enjoying a long jamming crack pitch. I was nestling in a deep hand jam when I felt something moving in its depths and was startled by a chorus of high-pitched squeaks! Quickly shifting my hand to another position, I stared into the darkness of the crack only to be met with a cluster of beady eyes and the gnashing fangs of a gathering of bats who were not best pleased with being disturbed from their beauty sleep.

Once, to my horror I jarred and dislocated a shoulder when a foothold snapped unexpectedly, leaving me hanging from a hand jam. Luckily for me, it sickeningly clunked back into place as I gently tried to move it. I will never forget the pain or the fear of the consequences. At that point I was committed to the route so I had no option but to continue upwards, but as it had trapped the nerves and left my arm in a weakened state it was a tenuous and careful exit.

On occasion when soloing, be it because you are in the wrong place or in the wrong state of mind, brash moves are made or forced. I have learnt over the years to listen to my mind and body. For example, if you trip over your shoelaces on the way to the crag, take it as a bad omen and just enjoy the views. But there have been one or two instances when I've ignored the signs and ended up being forced out of my indecision by a ticking clock and literally getting away with things by luck rather than judgement. Those experiences are truly frightening and embed themselves in the dark places in your mind that come back to haunt you.

Lastly, being caught in an unexpected rain shower while soloing on E grade slate slab routes does not come under the heading of Fun! Luckily for me, someone lowered a rope as I was stood on the only remaining dry patches. Always expect the unexpected.

Strong foundations: Learning to play with fire

I am a believer that 'what comes before' sets you up for the future and the skills we gain and fine-tune through play in childhood can form a large part of the direction we take and the situations we can deal with as we grow.

The cycle flipped end over end and landed on its side, the knobbly tyre still spinning on its buckled front wheel. A 9-year-old me picked himself up off the ground, dusted himself down and inspected the grazes and gashes through torn clothes. The stunt had been destined for failure from the minute the wheels started rolling at the top of the steep hill. Gathering speed towards the ramp, the bike hit the makeshift ramp halfway down, sending me high into the air. Unfortunately gravity had its own plans and instead of landing smoothly on the back wheel in control, the bike took a nose dive and planted its front wheel into the dirt, spitting me over the handlebars and sending me arse over tit down the hill to land in a heap at the bottom.

My childhood was full of risk-taking. It's part of growing up and finding out who you are and what you're capable of. If there was a danger element, then it always cast a spell on me.

As a youngster I was always willing to attempt to give my hair-brained schemes a go, whether it was bike stunts, climbing up buildings or trees, jumping gaps or playing dare with cars—I was always in for the ride.

I learnt to convert my overactive imagination into 'visualisation' at a young age and with the help of some larger-than-life characters in the form of a web-spinning comic book hero and a maverick motorcycle stunt rider going by the name of Evel Knievel as role models, it's no wonder that both climbing and motorcycles have featured heavily throughout my life.

When I think back, bruises, grazes and breaks were acquired like an extreme form of stamp collecting. They were worn with pride and, in the long term, the ongoing fine-tuning has got me to this point in one piece.

The whole idea and concept of active risk taking and the psychology behind it has always fascinated me. Why are some folks happy to take on risks and consequences which many find unacceptable? I am sure science has the answers involving chemical reactions in the brain causing stimulation, which would destroy my romantic ideals as I am more interested in individuals, their own personal motivations and what makes them tick.

Everyone who climbs does so while acknowledging perceived dangers based on their own personal level of skill, regardless of grade—who is to say that one climber can't get the same buzz and fear from climbing say, 'Severe' as someone onsighting at E6?

We all have a perceived limit, whether that is a physical technique or a psychological cut-off where self-preservation kicks in. What interests me are those that really climb knowing they have something to lose: on solos, bold hard routes, loose routes, new routes in isolated locations etc. Those that actively go looking for that fine line and thrive on the journey; a journey that switches very quickly from the body physically taking the mind on a ride to the point where the tables turn and the mind is taking the body. The point where, without mind control and acceptance of risk, you just can't get your body to perform.

I know from my experience that self-confidence and self-belief play a major part. I have built a strong foundation over a lifetime from accepting and taking the risks and getting used to what it feels like to be in that situation. One thing is certain: if it floats your boat, it's addictive.

The art of climbing is much more than the sum of its parts. It's not just down to the physical act or the outcome—it's the overall process. I feel privileged to have found my outlet through climbing and all its depth. I have enjoyed the process and journey to build the hard-won skills and judgement which allow me to take my personal climbing and operate with what the natural environment throws down, enabling me to become completely engrossed in its rugged splendour. This is why adventure trad climbing has always been my poison of choice. It has allowed me to follow my heart, to find my own ideals, it has allowed me to create and has given me something which has totally consumed me above all else.

If you play with fire for long enough, you are bound at some point to get burnt. Gravity is a hard taskmaster and dishes out strong lessons. If you are pushing the limits of what you feel capable of, things don't always go to plan. In recent months, my lockdown brain has been thinking back to the close shaves and near misses I have had. Here, for your pleasure at my expense, are some incidents, accidents and experiences I have picked out from the past 30 years—any one of which could have ended with a different outcome.

Dyer Situation

Through my disorientated confusion the sky looked strange, heavy-hung and grey with rounded mammatus clouds. I saw the white spots at the end of the tunnel closing in and felt the fuzz of approaching blackout.

The day had started with the usual excitement and expectation of creating a new route on the sea cliffs in North Devon with all the associated complications and uncertainty. This particular escapade was of a more serious and unpredictable nature, even for the Culm coast, as the climbing was based on the sandwiched bedding plains which made up the strata and consisted of compacted mud and rock. In the winter these bedding plains were often a soft rock/mud mix, but in the summer the heat baked it to form a solid(ish) mass.

It was quite obvious that standard climbing protection was not going to cut it, so we had to beg, borrow and steal a stash of 'Warthogs'—long spike like pegs which are used for ice and snow in winter mountaineering—which we planned on driving into the baked mix as and when the features allowed.

My partner for the day was Nick Dill, no stranger to the coast; a talented climber in his own right and never one to shun a challenge.

The proposed route was on the flipside of Walk of Life at Dyer's Lookout. The first pitch offered an alternative start to Pat Littlejohn's classic horror show Earth Rim Roamer 2 and had gone well, giving interesting gymnastic climbing around E4 on more traditional protection.

I set off from the first belay with my jangling bunch of warthogs and other pegs and headed off into the unknown.

Moving up the soaring sandwiched rock strata on pinches and lay-aways, I made swift progress, stopping to tap in the long spikes and blades where I could. As the rock steepened, I changed my approach to one of counter pressure, pushing out in a bridged position for both hands and feet, making small, calculated moves to gain height and keep the fragile holds in place.

No stranger to climbing on loose rock, I felt I had about as much control over the situation as was possible with just the right amount of adrenaline to keep things focused.

I had gained some height now and was well into the pitch. From my precarious position, I made the decision to belay on a small ledge that I could see a little further up. I very carefully tapped in a short knife blade peg level with my chin while holding myself in place by bridging. The peg slid behind the block way too easily and the hollow sound did not inspire confidence! Still, what could I do? I was in the situation now and no amount of crying was going to sort the problem. Push on.

I made a tentative move up, pushing with my hands to advance my feet then re-locking my feet with pressure to advance my hands. Breathe. Try to relax...heart pounding...deep breaths…Slowly. In through the nose, out through the mouth.

With closed eyes, I tried to centre. A little self-chat to convince myself I wasn't alone. A few more moves and I would be on the belay ledge, although it didn't look as welcoming as I had hoped as it was narrow and sloped downwards.

I scanned the wall behind it for belay placements. A couple more moves and I would reach my island of sanctuary.

To this day, I still don't know what happened. As I moved up above the blade peg, I released the pressure on the holds and...SNAP!

The mind plays funny tricks when in imminent danger. In reality, these things happen very quickly but the mind seems to overview the situation in slow motion whilst at the same time trying to process everything at turbo speed. It's like an out of body experience. For a split second there was a deadpoint of nothingness and silence before gravity took control. I started to fall backwards.

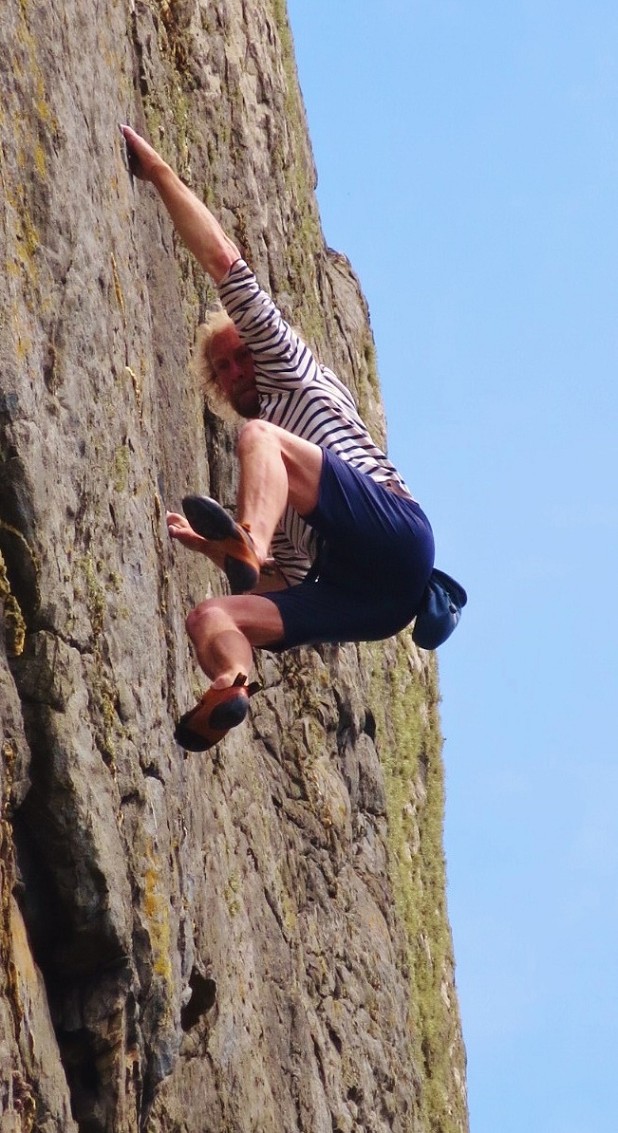

When you're climbing on this weird, unpredictable rock with sketchy protection, it pays to climb on double ropes, but it is not always easy to be totally aware of where they are in relation to your feet as the climbing is so three-dimensional. In the ensuing fall, I made a rookie mistake. As I fell, one of the ropes caught my heel and flipped me upside down. As I accelerated backwards, I had a perfect inverted view back up the crag and saw the top blade peg rip from the block!

I hit the arête with a slam and continued to gather speed as the second Warthog exploded from the wall, spitting me onto a spine of rock further down. I remember thinking: 'SHIT! This is gonna be a big one!' I felt a further two Warthogs pop like press studs from the rock, my downward progress interrupted by my collision with protruding rocks.

I came to a halt on the last remaining Warthog and hung, stunned and disorientated, inverted in my harness, staring down at the grey mammatus cloud-like boulders. In my state of shock, I slowly tried to right myself and my initial reaction was to start laughing hysterically at the absurdity of the situation. I was staring up at Nick having fallen the length of the pitch, passing the belay and stripping out all but one piece of gear. It was then that the pain in my hip and femur hit me and I was engulfed in nausea. I hung there in silence for what must have been 15 minutes before I could overcome the need to pass out each time I tried to move.

Nick hoisted me up onto the belay and set up our escape abseil to the beach.

It was a close call and I was lucky to escape with bad bruising. Needless to say, I have not returned to try again and the line still awaits an ascent. Any takers?

Diggin' for fire: Mind games and recollections of ascent

When you have climbed obsessively in an area over a long period, inspiring routes at your limit can dry up. I was coming to the point where I had climbed everything that inspired me up to my onsight ceiling. One day, whilst scanning the North Devon & Cornwall guidebook, Naked God jumped out at me.

The dark face of Blackchurch in North Devon is an intimidating place to climb. Over the years I had climbed everything else on that right side of the wall and had particularly enjoyed bagging the second ascent of the superb soaring arête of Lord Bafta. Time to take another look.

Naked God E6 6b sits to the right of Lord Bafta's arête and takes a 45 metre journey through a fine sheet of blank slab into the heart of nothingness. Both routes were '90s creations by the bold South West climber and unsung legend, Frank Ramsey.

At the time I had been re-repeating the big routes on Smoothlands' Great Slab and eliminating their pegs, so I was tuned into the style. I climbed with a local, Dan Gorvett, who wanted to follow me up these big lines. When I approached him about the Blackchurch route, he was keen.

I picked an early evening to allow the crag and my Raynaud's-prone fingers to benefit from some late rays of sunshine and we set to it. We got established on the small ledge at the top of the scrappy first pitch and made a semi-hanging belay just right of Archtempter's soaring groove.

Looking up from the stance, the route looked huge with no glaring line making itself clear. The guidebook said 'a powerful line tackling the smooth expanse of rock' with the additional words 'very bold' thrown into the mix more than once as well as the inspiring mention of 'skyhook runner' and 'short knife blade peg' to draw you in. I realised that at its original grade of E6 6a, it was going to provide quite a ride.

In all the years I had climbed in the area I had never seen anyone anywhere near it and, at that time, I was not aware of anyone having repeated it, so I thought I was about to embark on the second ascent.

Knowing the unpredictable nature of rock on this coast and contemplating the condition of its ageing pegs, I was starting to think it would have been wise to abseil the line first, rather than going for the onsight, but from my experience of the coast I convinced myself that I would be able to back them up to ease my passage.

I stepped into the unknown and straight into some bold climbing. I placed a skyhook and followed a parallel line right of 'Godspell'. At the top of the initial wall Naked God briefly joins Godspell at a good stainless steel peg, after which it climbs a rising line rightwards into the middle of nowhere. Little did I know that this was the last piece of reliable gear and by the time I reached the next friable peg, I realised there was no going back. Despite the fact that I would not have hung my coat off it, I clipped it and tried to back it up as best I could. I closed my eyes took a few calming breaths and pushed on.

The face was made up of small 'After Eight'-sized edges and flakes, which provided crimps and sidepulls that creaked when pulled on, so I reverted to the Culm Coast art of pushing them in whilst pulling down to keep them seated. What I used for my fingers I then had to use for my feet, so they didn't offer much respite for screaming calves either.

Moving up via the right choice of holds felt like a game of high stakes Jenga. I dealt with what was in front of me and linked things together in small moves, not letting my mind get flooded with the big picture. Running it out is mind-frazzling at the best of times, but running it out on protection that is unreliable at best is not something to ponder on. I didn't think I had placed a piece of pro I was happy to sit on, let alone take a fall on. I had no 'Get out of Jail' card and was committed to the ride. There is nothing like a touch of fear to sharpen you into climbing your best.

Many people enjoy the movement of slab climbing; it creates a feeling of masterfulness in the balletic motion of dancing on tiny edges. It's not about how strong you are physically. It's about footwork and flexible hips and while seconding or top roping without the fear of commitment, all is well. Leading is a different ball game; you can climb yourself into No Man's Land. Stand in balance and contemplate your predicament and its consequences. It becomes a deep mind game when you throw a potential ground fall into the mix with little room for error. My mental biceps were working overtime. I can't say I wasn't enjoying myself, but I was acutely aware that this was serious fun.

With no going back and no chance to bail out, I continued to move up tentatively, making precise moves and spreading my body weight across all the small edges and hoping I would arrive at a sinker nut placement to dispel the fear. I felt tense and resorted to internal dialogue to calm things down. Steady as she goes. Focus on breathing. Concentrate on feel. I continued adjusting my body position in small increments to achieve smooth moves. In these situations where brash moves have consequences, the worst thing you can do is lose it. You have to have faith in your ability and keep things simmering.

I remember one section distinctly; having pulled up I made a move right to reach a foot edge about an inch wide—an island in a sea of chaos! The problem is that these small rests break the spell and are hard to leave. I balanced there a while, attempting to fiddle in protection: an RP and a 0 cam on two lobes was the meagre reward for my efforts. It then took a few tries to leave them and make the tricky moves up and left.

With the first ascent pegs all replaced, it would have been bold but at least I would have been climbing from one island of safety to another. Knowing these rotting relics would snap like biscuits and finding worthwhile protection among the creaking flakes was proving difficult. It was probably the first time in my climbing life when I was fully aware that a fall was unthinkable and I really felt under pressure.

It felt like I was 'Out There' for quite a long time, teetering around in nervous energy. Now three quarters of the way up the slab, I could see a little higher up; it would ease, but as is often the case with sea cliffs the rock starts to deteriorate near the top, so the rock demanded respect and dictated that I make no false moves. The tension remained high until I clawed at fistfuls of grass and pulled over the top. I screamed with the joy of success (or was that survival!)

I lay back in the grass for a while staring up at the cloudless sky and taking in the quiet of a now settling mind, feeling not so much elated as stunned. When Dan arrived wide-eyed at the top we sat back in the grass and laughed at the craziness of the journey.

Later, in a more serious tone, he asked me what would have happened if I had fallen. I shook my head and screwed up my face. "Best not go there!"

To knowingly dance in the danger zone through your own choice and dig deeper than you thought you could, to keep everything under control, to use all of your technical skills and tactics to play the long game of trad onsight climbing results in an intensity I have never found elsewhere.

Naked God certainly provided an experience. It wasn't at my grade limit. It just combined elements at the right time for me to enjoy its challenges and get away with it: bold, sustained climbing on unpredictable rock with poor, unreliable protection on an uncertain line forced me to draw on years of experience in a situation that could have ended differently. It has left a lasting impression and could certainly fit into the category of ... A Close Shave.

**Note** I found out later that the second ascent was done by an on form Ian Parnell many years earlier (probably on good pegs!) and the talented James McHaffie has repeated it since my ascent.

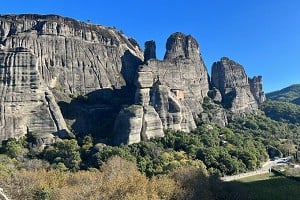

- ARTICLE: Lines in the Sand - Crack Climbing on German & Czech Sandstone 26 Feb

- CRAG NOTES: Dunderstruck! 31 Aug, 2021

- ARTICLE: Extreme Culm - Recollections of Climbing on the Coast 21 Oct, 2020

- ARTICLE: Far and Wide - Offwidths Around the World 18 Jun, 2020

- DESTINATION GUIDE: A Masochist's Tour of Cornwall's Offwidths 2 May, 2019

- ARTICLE: Hostile Terrain - Trad Adventures in North Devon & Cornwall 23 Oct, 2018

Comments

Brilliant, Stu! I can relate to so much of what you say about soloing although I've not done much of late. My own weirdest "expect the unexpected moment" came while soloing at Stanage early on in my soloing, and noticing a strange dusty texture on all the holds half way up, increasing the technical challenge significantly... Turns out it was some poor sod's ashes poured down the face! Grim and ironic, had it caused me to fall off.

Impressive stuff!

I've met similar at Froggatt, on Nursery Slab (M) which is the descent route - however they may be ashes of someone's pet rather than a someone - not sure that makes much difference.

I really enjoyed that.

One minor quibble that is unrelated to the article itself but is the case on a lot of editorial posts, it would be very helpful if the article photos actually linked to the climbs on the database. Sure, I can just find them anyway but since it is a feature of the system, why not? :-)

Glad you enjoyed it & thanks for your comments, I think in past articles the routes have been highlighted in blue & when clicked take you to the relevant route...not something I can do from my end though.

Thanks again, all the best, Stu.