Mick Ward used to dream of a secret crag: 'It was never in the same place twice. And, when I'd wake up, it seemed so real, yet I couldn't remember where it was. (Well, of course, it wasn't anywhere...but let's not spoil the illusion!) The only person I ever told was Geoff Birtles and he came straight back with, "Well I've got two crags I dream of - one on grit and one on limestone." Typical...' Perhaps, for many climbers, there's a dream crag; an archetype which we yearn for. This was Mick's dream crag - with dream routes to match.

His dream crag, the lost outcrop, lay forlorn and forgotten on the bare hillside. Yet twice it had given the hardest route in Britain.

In memory of Brian Cropper, who loved moorland grit and

Harold Drasdo, who dreamed of a valley of huge, silent crags.

A long time ago, on unfrequented shelves in a private library, he came upon the classic series 'Climbs on Gritstone'. Those old guidebooks were his initial, vicarious experience of the world of outcrops. Pete Biven swung free from the lip of Quietus, suspended in timelessness. The Dangler was 'for strong parties only...' Sentinel Crack cried out to the brave and the bold.

So much history: people, dates, climbs, places... atmospheres. 'A wet, misty day at the Ravenstones.' Intrepid souls at Den Lane, Upperwood, Yellowslacks. Hallowed names which would, in time, become a litany of personal devotion. High Neb, Burbage, Gardoms. Wimberry and Widdop. Shining Clough.

In his time, he learned to love gritstone the hard way, the only way, for this is its great gift. The moves merged in his mind, so that the cunning heel lock on Pebble Wall led into a delicate stemming of Crease Direct, was lost in the exquisite final smear of Piece of Mind.

'The moves are so easy; it's just making them that's so hard.'

The years passed; his apprenticeship was over. He'd been to Ogden Clough, to Baildon Bank, often to his beloved, then deserted Shipley glen. Grit was a private affair, an implicit passion, marred and diminished by the presence of crowds.

Blackstone Edge in spring, Derwent in autumn. Endlessly rediscovering the eternal secret. The moves are so easy; it's just making them that's so hard.

Of course he went elsewhere. Bowden and Armathwaite continued the idiom. And there was always the pocketed creaminess of limestone. For differing perspectives, there were the Lakes and Wales and Cornwall. For fun, the Aiguilles; for space, the Verdon.

But the dream had begun long before, with grit. And because our lives are the living out of our dreams, he had to return, time and time again to that grey, primordial stone which had spawned and nourished his passion.

In his way he became a connoisseur of outcrops, yearned for the joy of fresh encounter. Slipstones and Scugdale. Gilstead and Shooter's Nab and even Pule Hill.

In time he dreamed. Dreamed of the one outcrop which yet eluded him, revisiting it endlessly in reverie, learning to love the harsh imprint of its contours upon his palms. Each time, the memory weakening, fading. Afterimages lingering...

Sometimes it was deep in the Churnet, often high upon a bleak hillside above Halifax or Huddersfield. Once near Keighley. Sometimes it reminded him of Dalkey. It was always somewhere else.

The contrasting passion of his work demanded a quotidian drudgery upon the great arterial motorways which endlessly pump travellers the length and breadth of England. He would criss-cross the Pennines from home to motorway, often going miles out of his way for the bright gleam of early morning light on the surface of Ladybower or the familiar, reassuring bulk of Kinder, high in the darkness above him.

And still he dreamed - dreamed of his lost outcrop, standing proud and alone on its dark hillside. The lost outcrop. The last outcrop. Forgotten by all. Who knew where or why?

'How, he asked himself incredulously,

how could it have stood there, unfrequented for so long?'

It was close to him now. He felt it. The flicker of pale yellow light on isolated buttresses behind Longdendale hinted at its proximity. Soon he would be there again. This time he would find it - and remember.

The day was stifling, at the height of midsummer, his journey north from Birmingham a constant snarl of tailbacks and contraflows. Near Knutsford, on the M6, an articulated lorry had jacknifed, disgorging its cargo of plastic mouldings. He eased past with trepidation and made for the M56. His back ached; rivulets of sweat trickled down his spine. The air shimmered with petrol fumes and heat haze.

Past Glossop he began to relax. Almost there now. And yet, more than ever, he knew the need for caution. Up ahead, a lay-by yawned invitingly. Wearily, gratefully, he pulled in. Five minutes, he promised himself - no more.

His seat tilted back. The keys swung from the ignition. The blessed warmth of oblivion rushed to meet him. Before the keys were still, he was gone.

This time, for the first time, he could see it clearly, standing on the bare hillside above him. Small, compact, clean, unyielding. Seventy feet high at most, yet every foot mattered. A prominent roof guarded the centre of the crag. How, he asked himself incredulously, how could it have stood there, unfrequented for so long?

'A lead was considered 'unjustifiable'...'

Apart from shepherds, the earliest pioneer must have been James Puttrell, in the early 1890s. Although he climbed the deep, left-bounding chimney which bears his name, little else proved feasible. George Bower was next, some thirty years later, adding a companion route to Puttrell's, at the other side of the crag. Bower it was who first drew attention to the centrepiece, the great hanging slab above the roof. Diary notes mention a rope-assisted inspection of a possible line upon that slab. Bower gave, as his opinion, the angle of the slab to be, 'at or beyond the very limit of frictional adhesion' and surmised that a lead, 'would involve little more than moral support from the rope.'

The 1930s saw two visits, the first from Eric Byne and Cliff Moyer, drawn by the allure of Bower's great hanging slab. Both failed to toprope it. A lead was considered 'unjustifiable'. And so the line waited.

'It was the boldest and hardest lead I have ever witnessed...'

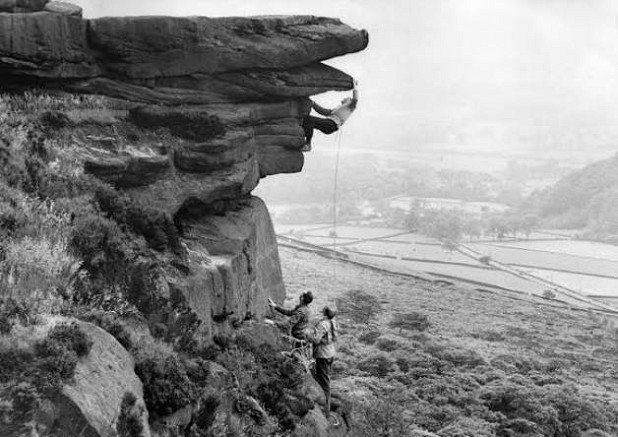

Waited a further year, until the advent of Colin Kirkus and Alf Bridge. Body-belayed by Bridge, precariously straddling the depths of Puttrell's Chimney, Kirkus gingerly traversed onto a tiny, sloping ledge at the base of the slab. 'From there, I ascended directly...' The characteristic diffidence of Kirkus' diary entry gave no indication that the route was, by many grades, the hardest on gritstone or indeed elsewhere in the country at that time. Bridge, who needed a rope 'taut as a bow-string' to follow, snapped a crucial pebble. Typically he was more forthright. 'It was the boldest and hardest lead I have ever witnessed.'

Another decade passed. Kirkus, the gentlest and most decent of men, had died on his way home from the molten flesh of Bremen. His route, unnamed and unknown, paid silent vigil on the lonely hillside. There were no suitors.

Much later, the eminent Polish mountaineer, Dr Kuba Bujak, did an obscure line to the side of Puttrell's Chimney. He meant to return but never did. Instead, while on a climbing holiday in Cornwall, he vanished.

In the 1950s, Bob Downes resolutely attacked the obvious central roof crack. Forced into using three slings for aid, he nevertheless reached the temporary sanctuary of what would later be known as Kirkus Ledge. Daunted by the potentially fatal runout above, he unwittingly reversed the traverse into Puttrell's Chimney.

'...completely unprotected and poised above an horrific void.'

Jim Perrin and Tony Shaw were next, in 1969, the day of the first landing on the moon. After protracted effort on Downes Crack, 'two grades harder than Quietus', Perrin freed it, to also reach Kirkus Ledge. Not knowing anything of Kirkus' earlier ascent, he 'tiptoed into the unnerving blankness...' A delicate high step onto a curving ripple near the top of the slab was, 'the boldest move I've ever done, more technical than the crux of Daydreamer, yet completely unprotected and poised above an horrific void.' Frantically he lurched for the top, terrified and amazed to still be alive.

On the drive back to Manchester, Perrin pondered name and grade. For the latter, XS would suffice; back then, it covered a multitude of sins. Naming proved somewhat harder. He'd always loved The Enigma of the Hour, Giorgio de Chirico's classic evocation of timelessness. On the crux move, with his life literally in the balance, it was as though time had stood still. Yet clearly such a title would invite ridicule. While Drummond had got away with A Dream of White Horses on Gogarth, in Yorkshire, Two Ton Sardine had been brutally discarded for Shuffle Crack. No, The Enigma of the Hour wouldn't do. But why not simply... Enigma?

‘…the first proper Extreme on grit…’

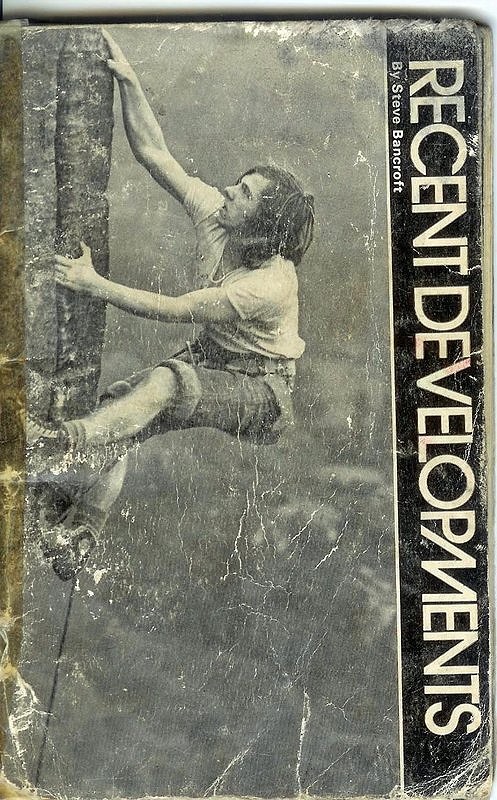

Throughout the 1970s, the aptly named Enigma garnered a legendary reputation amongst gritstone cognoscenti. Most suitors failed on Downes Crack; the few who reached Kirkus Ledge unwittingly followed Downes' example and fled to the sanctuary of Puttrell's Chimney. Al Manson sardonically quipped, 'it's the boldest route I've never done.' Steve Bancroft wrote it up in Recent Developments as, 'the first proper Extreme on grit', thereby inciting even more attempts and more rebuffs. Although a nonchalant solo ascent by Andy Parkin was rumoured, it's likely that Enigma, a paean to boldness and technicality, had to wait more than a decade for its second ascent from Dougie Hall in the 1980s and yet another decade for its third ascent from Seb Grieve in the 1990s. Seb it was who first suggested the then outrageous grade. Undaunted by the resulting controversy, he persisted, "Looks like some of those old boys could climb harder than anyone imagined!" Inevitably it was suggested that Perrin hadn't done it. However a single, faded snapshot from Tony Shaw's camera told otherwise: a desperately lonely figure, limbs splayed out on the crux, ropes dropping into the void, the last runner far, far too far away.

‘…a paean to boldness and technicality…’

As Peak Rock noted in 2013, 'Enigma Variation was the hardest route in Britain by several grades. Amazingly it was climbed by Colin Kirkus in the 1930s and only credited to him many decades later, after diligent research by Steve Dean. A side-runner in Puttrell's Chimney leaves the - as yet untested - option of a horrible pendulum. Could Bridge (or anybody else) have held a fall while straddling the chimney? It seems unlikely. Failure on the first ascent of Enigma Variation would almost certainly have resulted in death for both members of the party.’

‘…a fine place to ponder the frailty of human existence.’

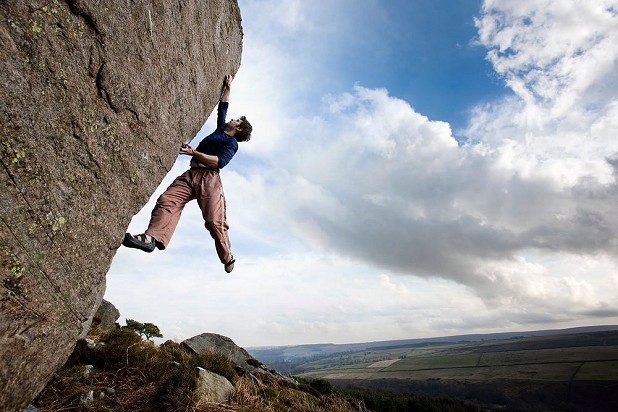

‘The addition of Downes Crack makes the direct route, Jim Perrin's Enigma, much more demanding. Once again it was the hardest route in Britain and the first of its grade. The temporary sanctuary of Kirkus Ledge is a fine place to ponder the frailty of human existence. The crux slab will always remain a testimony to gritstone boldness. Even with the most modern of micro-cams, the highest runner in Downes Crack is still unlikely to prevent a sixty foot groundfall.'

'…an exquisite blur of controlled motion, so high above that empty moor…'

So... after the dream route Enigma, what could possibly remain? With a keen eye, he scanned the compact buttress, searching for inevitable omissions in his predecessors' perceptions. Nothing. Nothing? Except...what about the right-hand bounding arete?

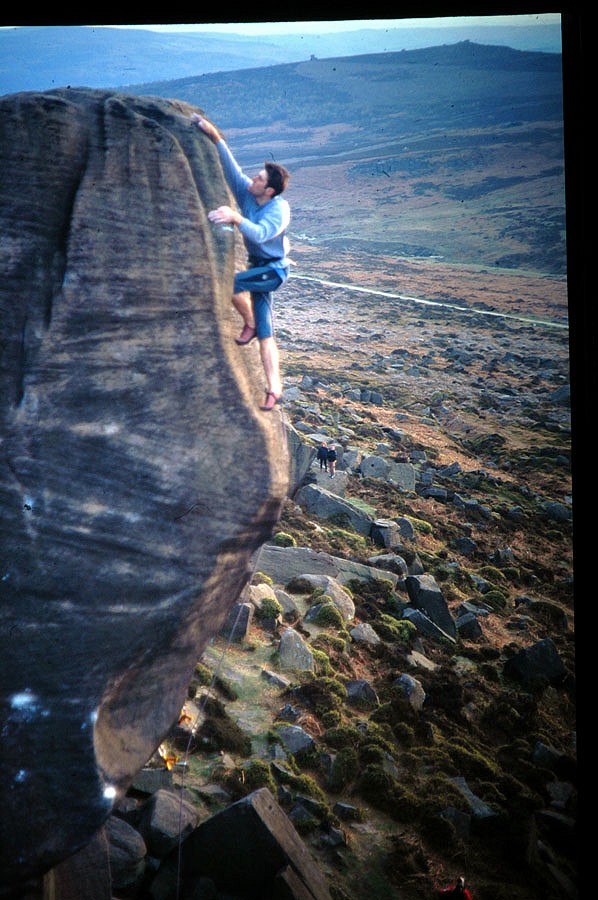

The initial moves were even harder than they looked. Intricate edging on suspect pebbles culminated in an achingly long, irreversible stretch for the first break. It was rounded, uncompromising. Desperately he smeared in shallow pockets. Above, the arete bulged menacingly; beneath, the hillside dropped sharply away into a jumble of heather-filled boulders. The thought of jumping off was stomach-churning.

Go for it then. Chalking up, he fiercely pinched the blunt arete. Smear and reach across. Both palms together. Pinch and press. Balance. Smear again. Balance. The apex of the bulge. His and its limit. Slap or -

Got it!!! Taut fingers cutting into the faint crease, toes running up high, wriggling into tiny pockets. A wild layaway on the now sharp arete. The final ten feet, an exquisite blur of controlled motion, so high above that empty moor, were better than it would ever be again.

Bounding happily down the stark hillside, he turned once to glance back. Warm sunlight bathed the sturdy tower of stone. His outcrop. Their outcrop. The lost outcrop. The last outcrop.

The last outcrop... He muttered restlessly in the drowning heat. A bluebottle buzzed in the back of his car. Slowly he came awake, to petrol fumes and the drone of traffic and the bitter, salty tang of hot dogs. The lost outcrop. This time it was gone, truly gone. Untroubled by hope, he reached for the ignition.

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

Comments