Mick Ward shares a fictional story of a talented female climber, whose course was altered by the dark side of 1960/70s hedonism...

(With gratitude to Ian Campbell, Calum Fraser, Pete Ogden, Reg Phillips, Brian Trevelyan and Chris Prescott for help with the photographs.)

She was so young, almost unbearably gifted, poised to utterly transform British climbing.

"Only five climbers – Crew, Yates, Willmott, Holliwell and Ward-Drummond - have previously succeeded on this, the most audacious route in Wales. Now we have a sixth. At just 17 years of age, Miss Lorna Murrion is the youngest and, some might say, the least experienced. Yet it's apparent that she has ability in plenty. No less a personage than Crew himself has described her as, "…the best climber I've ever seen. She's a complete natural. She'll utterly transform British climbing in the years to come." (Ken Wilson, Mountain Craft, 1967).

"Barty, I don't want to do it."

"Don't worry, babe - it'll be fine." But it was anything but fine.

Afterwards he lay back, satisfied, replete, a thin spiral of smoke curling upwards to the ceiling of the little flat above Wendy's. She buried her head in the grubby pillow, felt salt tears trickle down her cheeks. She felt diminished. And dirty.

***

"So - think you can do it, then?"

"I don't know. Maybe…"

Joe smiled wryly. "Show some confidence, Lorna. Show some bloody confidence, my girl."

***

The walk up to Cloggy was no less brutal than before. Her lungs rasped from too many cigarettes. They stopped at the Halfway House for home-made lemonade. A brief respite. Not brief enough though. She thought of Barty, who'd still been in bed when they left. He'd be downstairs now, busy chatting up that new girl in Wendy's. Harris fancied her too. But it'd be Barty who'd get there first, she reckoned. That boyish charm, the sheepish smile that melted your heart, even as you knew you were going to be royally fucked over, one more time.

Close up, the face looked blank - bloody blank. Well that was the whole point, wasn't it? That's why Brown hadn't managed it, not with his ration of two points of aid, per pitch. 'This is crazy,' she thought. 'Two years ago, I was a beginner at Windgather. And Brown was God. Now it's as though I'm challenging God Himself. How can you challenge God yet feel so dirty inside?'

Slowly, lingeringly, Joe and she uncoiled the two-hundred-foot ropes. "They're on loan for one day only," he joked. She looked across at him, smiled. "I'd better get it done then, hadn't I?"

***

Leaving the ground was always the hardest. A vile little voice in her head murmured seductively. 'You don't have to do this, you know. What difference will it make anyway? Your life won't change because of it. So why not just walk away… while you still can?'

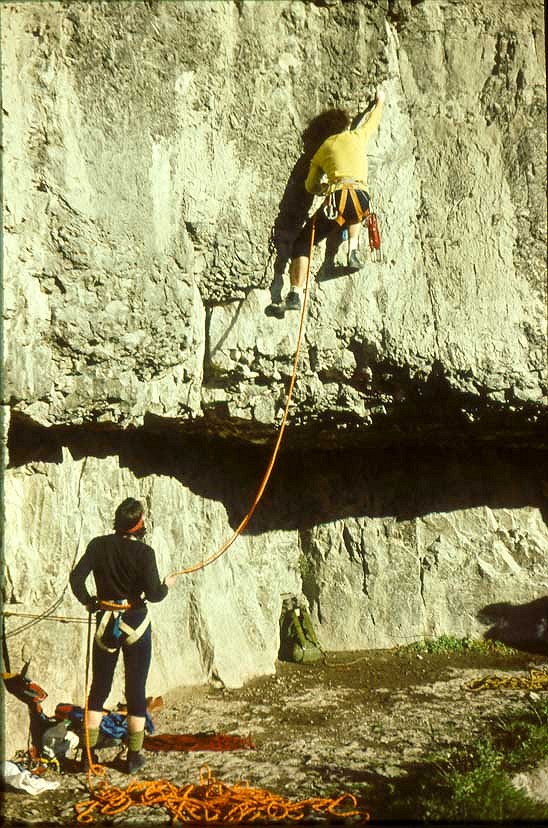

Instead she stepped off the ground, made a move up, then another, then another. Tried to fiddle a little garage nut into the first thin crack, wasted ten minutes but it wouldn't seat properly. The peg was only a few feet higher. Press on. She couldn't really work out the last move to the peg, just pulled on something, anything. Clipped it. Moved up again, found herself on a little ledge in the middle of the wall. Looking down. Twin ropes gently swaying in space. Joe's white face staring up at her from far, far away. A little knot of climbers standing near him, looking up, maybe concerned, maybe aghast.

So hard to leave resting ledges. You want to remain forever, not discard them like former lovers. She stepped off the ledge, made a move up, then another, then another. She looked down again, knew she'd hit the ground if things didn't work out. And they might not.

Breathe, breathe, she told herself. And go to where you've been before, that calm, gently removed place where it's as though you're standing outside yourself, watching yourself execute the moves with perfect precision. Breathe, breathe. Find that calm, gently removed place. Go to where you've been before.

Yet in the middle of the wall she faltered briefly, could hear a muffled gasp from the assembled throng below. She fought for composure as waves of unreality washed over her. Breathe, breathe, she told herself. Go to where you've been before.

And then finally, almost too late, it came, that cool, relaxed feeling which never failed to set her free. Finally climbing well, so well, climbing better than she'd ever climbed before. The thin, ragged crack loomed, twenty feet above. So much rope out now and so few runners that it wasn't worth bothering about any more.

At the top of the ragged crack, there was a long reach diagonally rightwards. Such a long reach for a girl, she mused. I guess those other guys were taller than me. 'But not necessarily better,' the inner voice murmured, finally her friend. Make that reach and the route was in the bag. She looked down at the bootlace thread wrapped round a split pebble in the ragged crack, so fragile, the heavy steel karabiner mockingly redundant.

Go. Just go. And she did. At the last moment, realising that the finger-jug was even farther away than she'd thought. Too late now. Only one way. Up. Tensing on a tiny edge. Reaching, farther, farther, farther still. A canvass of grey stone spread out below her. Fingers brushing the finger-jug, closing over it, latching it. She pulled through to thunderous applause, knowing with grim certainty that it was better than it ever had been before and better than it would ever be again.

***

"So what does it feel like to be the rising star of British climbing?" "I'm… not sure really. I don't feel any different. I guess I'm just me. The same as always."

***

"Barty and I are off, next week. Cham first, then Grindlewald. The Eiger." "But it's only had a couple of British ascents… are you sure you're ready for it?" "Well I'm crap on rock - as you well know. But I can move fast on ice. And Barty can lead the harder rock pitches. We'll be fine."

But they weren't fine. When Barty came back, he wouldn't meet her eyes. Wouldn't talk about Joe. She went to see Joe's heartbroken parents, coked to the eyeballs to get through the ordeal. They seemed to think she'd been his girlfriend. "I always wanted him to meet a nice girl," his mother confided. God, if only she knew.

"Try this babe, try this. The warm hand on the brain – but better. Much better. Takes away the pain. Takes away everything."

"I don't like needles, Barty."

"Just this once, babe. Just this once…"

***

Llanberis was a rapidly fading memory. She spent her days around Kings Cross, selling the only thing she had left to sell. Spent her nights in a squat with many others. Shared needles. Sometimes she saw Barty, most times she didn't. Wasn't surprised to learn he'd OD'd. Didn't go to see his parents. What was the point? In any case, she had more urgent things to consider. Would Barty's parents have considered her 'a nice girl'? Somehow she doubted it.

***

Years passed. London, Liverpool, Newcastle, Birmingham. The cities were different, her life was essentially the same. You didn't have friends; how could you, when all of you were competing for the same thing? A friend was someone who would betray you tomorrow. You only had one friend. She knew that one day it too would betray her, as it had betrayed so many before.

***

"Lorna? Lorna Murrion?" "I… I'm sorry." "Lorna - don't you remember me? James Campion. We met at Carreg Alltrem. I was gripped shitless on Lavaredo Wall. You soloed across and placed a runner for me. You saved my life, that day. I've never forgotten you."

***

Rehab. A lot of time. And an awful lot of money, she reckoned. Some interesting companions. A novelist who'd become famous overnight, after four decades of soul-destroying struggle. The highest paid star on television, whose career had been terminated abruptly. She didn't say much about herself, refused to 'unburden' herself in the obligatory therapy sessions. "You've got to let it out, my dear, you've got to let it out." But she didn't let it out. Her childhood was a sealed room, forbidden to anyone, even her. Especially her. Llanberis? Another sealed room. Afterwards? More sealed rooms. She had a haunted mansion of sealed rooms. Be that as it may, the dosages steadily decreased. She even gave up smoking. She knew though that she'd have to be unremittingly vigilant for the rest of her life. When you've indulged, you've indulged.

Afterwards she went back to Oxford to live with James. God, he was a nice man. A physicist at the university. Tall, bearded, gangling, bespectacled. She remembered how terrified he'd been on Lavaredo Wall. He'd tried to run the two pitches into one, had pumped out on the crux bulge, would have peeled and splatted himself on the ledges below if she hadn't soloed across. Maybe, as he insisted, she had saved his life. Both of them knew he'd saved hers.

He was gentle, undemanding. She never knew what he saw in her but clearly he saw something. And he was resolute. Early on, there was a brief, overheard telephone conversation. "I'm sorry, mother but Lorna is an integral part of my life now. In fact she is my life. It's non-negotiable."

From earliest days he'd been brilliant at school, went to Oxford with the brightest people in the country, remained brilliant, well at least at physics. Had been talent-spotted early on and given lavish research facilities. His colleagues were in awe of his brilliance. His gentleness was beguiling. Didn't really join in the social scene, lived quietly with that strange girl. On the obligatory occasions when he had to make a social appearance, she was never with him.

James had somehow believed he'd be brilliant at climbing too, had been shocked to discover how hopeless he actually was. Somebody had once noted caustically that Crew was the wrong build for climbing, "and yet he still did it." James applied the same rationale to himself but somehow it never worked. Undeterred, he hung around on the periphery of the university climbing club for years. He liked the company of climbers. Lorna never talked about climbing.

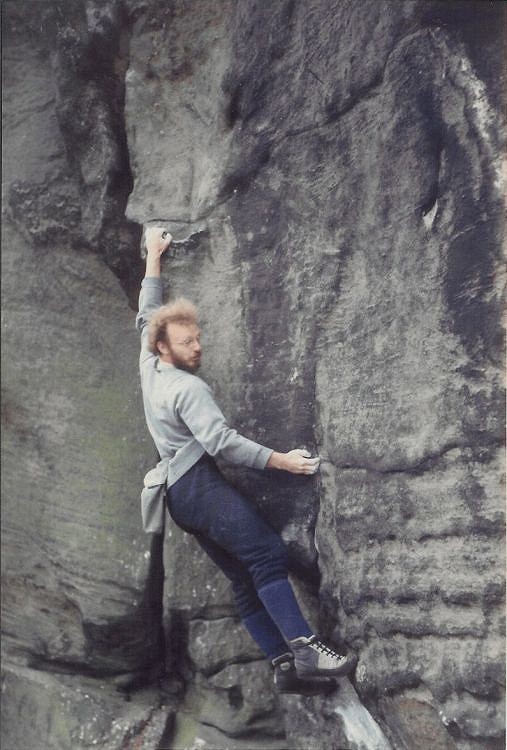

She came away with them just once, in the golden summer of '76. They drove up to the Peak and camped near Hathersage. They went to Stoney and the leading light in the club threw himself unsuccessfully at Scoop Wall, taking a monster lob from the bulge and almost hitting the ledge. Lorna had been playing around on the start of Our Father, once the hardest route in Britain. On impulse, she borrowed a Whillans harness, far too big for her and a couple of slings. James belayed as she attacked the vicious hanging flake. She was up it in seconds, clipped the mouldering peg, rested. Moved out across the bulge and clipped the single piece of tat. Rested. Then moved up smoothly to the undercut, with immaculate precision, placed borrowed EBs high on the overhanging wall and pulled through easily to the sanctuary of the cave stance. Nobody could second her, nobody could even get off the ground for more than a few seconds, so she abseiled to retrieve the two runners. A figure, clearly the leading light, detached himself from the watching throng below. Lank hair, a thin, undernourished face, watchful eyes brimming with intellect. "Good effort, love. First woman to do that. I'm Steve - Steve Bancroft." She shook his proffered hand. "I'm… Lorna." There was a telltale flicker in his eyes and she knew that he knew.

That was the only time she went out with the university climbing club. As the rumour machine surged, James and she became even more reclusive. Christened Lorna Jane, now she became Jane, Jane Campion, although they never married. Much to his mother's displeasure. They could never have children, not after what her insides had been through. They didn't speak about it.

Years passed. Decades passed. She got qualifications, not like his of course but enough to do what she wanted to do, which was to teach kids with learning difficulties. She didn't talk about her work, in some quarters was revered for the devotion which she brought to it. The kids loved her. On some arcane level that isn't on any psychological scale, they understood her - and she understood them.

Trying to make sense of the world, she read voraciously – but not about climbing. It remained a sealed room in her memory.

Once though, she was in the waiting room at a dental clinic and idly chanced to pick up an old Sunday Times magazine. An article written by somebody called Peter Gillman. 'Das Bluejeans - Brits on the Wall of Death' An Historical Review of British Ascents of the North Face of the Eiger, from 1962 to 1995. A photo of Joe and Barty getting wasted in the Padarn. And the story of 'The Young Ones…'

'By 1967 the Eiger was fast becoming a magnet for the emerging new wave of young British alpinists. The prevailing ethos couldn't have been more stark. If you were hard enough and could climb hard enough, then you could get up well-nigh anything. Conditions, weather, fitness, acclimatisation time in the mountains - all these were secondary considerations. This 'go for it' attitude resulted in some remarkable ascents. It also resulted in an unprecedented number of fatalities, in what has subsequently been termed 'the Lost Generation'.

'In the summer of 1967, two young British climbers named Joe Burgess and Christopher ('Barty') Bartlett arrived in Snell's Field, at Chamonix. Within two days, they'd done the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses. They moved to Zermatt. Another two days saw the north face of the Matterhorn completed. They moved to Grindlewald. On August 21st, they headed up the north face of the Eiger, making very fast progress on the first day. On the morning of the second day, the pair split up. Bartlett descended the face while Burgess carried on alone. On August 23rd, he reached the summit but was trapped in a storm for the following five days. When the Grindlewald guides found him in his snow hole on August 28th, he'd frozen to death. Although many people regard his ascent of the north face of the Eiger as the first British solo, unfortunately this cannot be accepted, as he completed the initial, easier sections with Bartlett, albeit mostly unroped.

'For years rumours have abounded about the 1967 ascent. Crucially, why did the two men part company? At the time, Bartlett refused to be interviewed. He died, from a drug overdose in a squat in Brixton, in 1969. Formerly the two had been best friends, although it's claimed there had been a fierce row between them in the infamous climbers' pub, the Bar Nash, in Chamonix, several days before the Eiger ascent. Intriguingly both men were close friends with the legendary, vanished British rock-climber, Lorna Murrion.'

"Mrs Campion, Mrs Campion!" She looked up, startled by the brisk, imperious tones of the receptionist. "The dentist will see you now, Mrs Campion!" Numb, she stood up. Numb, she walked through into a room of clinical impersonality.

***

A new century dawned. James' career had gone into overdrive, there was talk of a shared Nobel Prize for something almost nobody could understand but would somehow make a big difference. He spent more and more of his time away at conferences all over the world. Sometimes she wondered whether he was faithful. He couldn't help but be tempted; he was a man, wasn't he? But somehow she felt that he was as faithful to her as she was to him. Did he miss having kids? Probably. He'd have been a great father.

And then came the news – chilling in its brutality. Lung cancer. Ironic for one who'd never smoked and ran five times a week. Advanced and inoperable. She watched him wither to a pathetic remnant. Round the clock visits to the hospital. Then the hospice. Finally holding his skeletally thin hand.

"I'm sorry, Jane… Lorna. I'm sorry. I was never good enough for you. Maybe nobody could have been."

After the funeral she sold up, packed in her job, moved away from Oxford. She hated leaving the kids, but every year brought more paperwork and more cost-cutting. She'd loved the job, loved the kids but knew she couldn't do it any more.

James had left her not only affluent but downright rich. Her tastes had always been simple; she had little need of surplus money, gave most of it away to charities who seemed serious about what they were doing. Moved up north, almost to Bradford, where she'd originally come from. Bought a little cottage high up on the moors near Oxenhope, lived there quietly with her paintings and her books and her music. Went running on the moors. Sometimes she'd go soloing, mid-week, at deserted gritstone crags such as Ogden Clough or Rylstone or Simon's Seat. Just take rock shoes and chalk-bag and a little food and water and run out and play once more on stone. If other climbers turned up, she'd move on before conversations had a chance to develop.

***

In 2015 she turned 65. The girl of the summer of love, back in 1967, still weighed almost the same, although now her shoulder-length hair had turned from blonde, through grey, to silver-white. She celebrated by going to Almscliff, remembered having visited it once before with a lovely young guy from Bradford named Jim Fullalove. Back then they'd soloed all the VSs and HVSs, those joyous routes, such as Overhanging Groove and Frankland's Green Crack and Great Western. She soloed them again slowly, savouring them, old friends who would never let you down.

Because it was her birthday present to herself, she'd broken her golden rule of deserted crags. Almscliff was a vast array of people, with prodigious numbers of bouldering mats. Hardly anybody doing routes. Nobody else soloing. She was a relic of a long-vanished era.

Some guys were trying the boulder problem start to Wall of Horrors. Again and again they'd reach for the cup-hold on the rib, only to power out before they could get it. Eventually they tired and got bored and wandered off somewhere else.

She looked at the route, wondered. Silly to try it without a rope or runners but maybe she could just do the start and jump off from the cup-hold. Why not?

The grass beneath the route had been worn away by the passage of innumerable feet. She unfolded a strip of cloth from an old work shirt, carefully placed it at the dusty base, put on her rock shoes, cleaned each one in turn and stepped on to the improvised mat. She rubbed spittle into the rubber beneath the toes until it squeaked. Then she reached into her chalk-bag, touched her fingers together, blew the surplus chalk away.

Leaving the ground was always the hardest. She smiled wryly at the memory. Not any more. Those days were long gone. There was nothing to prove and nothing to desire.

She got the first curving layaway with both hands, brought her feet up. Reached for the next curving layaway, more of an undercut this time. Shuffled her hands and feet. Brought her right-hand layaway a little higher. Changed her body position. Her left hand pinched the blunt rib and went up and over the cup-hold. Her other hand joined it. She hung for a couple of seconds, loving the feeling of being there. And then let go. The landing was more jarring than she'd expected. 65-year-old ankles need more protection than an old strip of faded cloth to land on.

She carefully dusted off the piece of shirt and tucked it away with her rock shoes and her chalk-bag. She wandered idly down, through the fields, away from the crag. From high above, a pair of keen eyes watched. The old timer had been following her progress for quite some time. Back in the dim recesses of memory, something stirred, perhaps a face glimpsed momentarily at an Al Harris party long, long ago.

He turned to his climbing partner and mused. "She's a natural, a complete natural… the best climber I've ever seen."

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- ARTICLE: The Vector Generation 21 May, 2020

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

Comments

Well done Mick! Weaving a line between the believable and almost believable... the factual and the almost factual... A great read!

Simply brilliant.

A fantastic and beguiling article Mick! Great stuff! :-) Cheers Dave

Inspired by Take it to the Limit perhaps?

Lovely Mick - very evocative.