Mick Ward shares another retrospective, this time of the 1960s climbing scene: The 'Vector Generation.' (With very many thanks to Geoff Birtles, Ian Campbell, Chris Harle, Chris Jackson, Tony Marr, Reg Phillips, David Price, Dave Smith, Rod Wilson and the late Ken Wilson for help and kind permission to display photographs of this unique period in British climbing history.)

The 1960s was arguably the coolest decade ever. 'If you can remember it, you weren't there...' The UK reeled under the concurrent influences of sex, drugs and rock & roll. Out on the crags, the bravest of the brave were making climbing history. This is their story.

In 1960 Joe Brown turned 30. For almost half his lifetime he had been the predominant British rock climber. Only Whillans had challenged his supremacy. The first ascent of Kangchenjunga in 1955 had secured his acceptance by the establishment. Conversely it had given Whillans yet another chip on his shoulder. Their famous partnership was no more. Whillans aside, by 1960 Brown knew that other, stronger climbers were starting to come through. But the hard years weren't yet over. In fact the best was still to come.

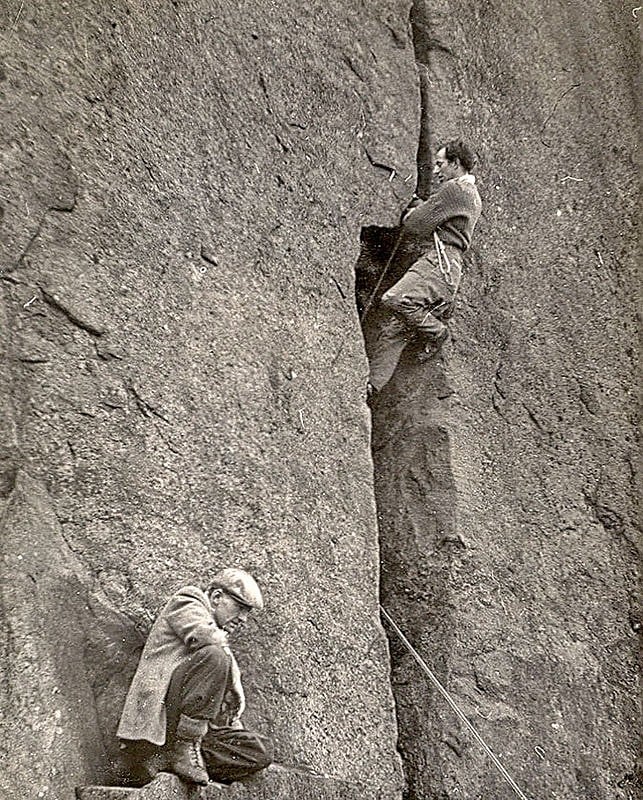

In the long hot summer of 1959, Cloggy came into condition for weeks on end. Jack Soper and Dave Gregory formed one team among many, securing early repeats of then-feared Brown routes. It seemed as though the mantle of invincibility might be slipping. Bonington recalled having once been spooked by Cenotaph Corner's intimidating aspect but then realising that, when you actually embarked upon it, the crack bristled with holds and hand jams. A teenage Martin Boysen casually remarked to Nea Morin, "It's OK - you can get a runner every 10 feet."

It looked as though the pack might be catching up with The Master. There were also a few ominous portents of things to come. Hugh Banner made the first ascents of The Hand Traverse and Troach. The Hand Traverse takes a stunning line above a vastness of space, while Troach demonstrated that Cloggy walls were not as devoid of holds as might be imagined. Look up and Troach appears blank. Look down and it's a ladder of jugs and little ledges.

Further along the crag, Boysen relatively easily seconded Brown on the first ascent of Woubits Left Hand, musing whether the top peg was really needed. Many years later, Banner would reflect that climbing was about 'jousting for crowns'. Brown must have realised that Boysen – more than a decade younger – was a likely contender for his crown.

Brown's riposte was inspired

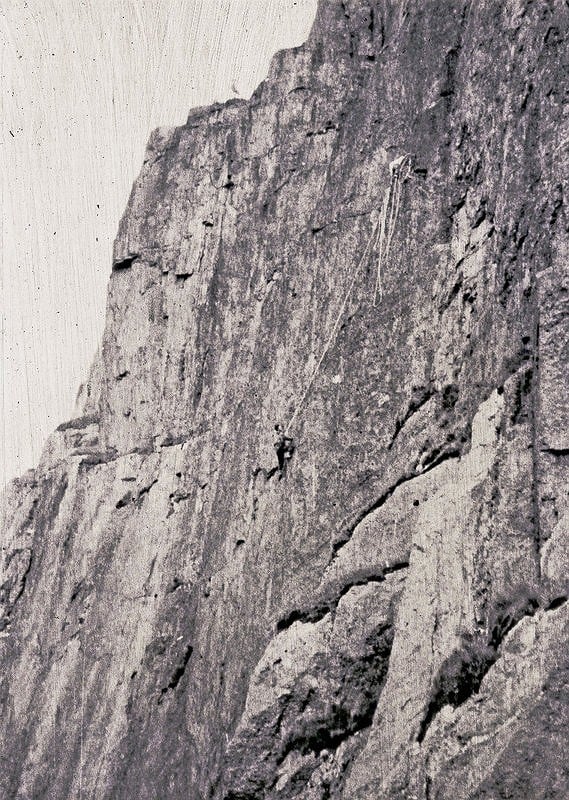

In March 1960 Brown made the first ascent of Vector. If Cenotaph Corner and Cemetery Gates had looked unlikely in the early 1950s, in 1960 Vector must have seemed utterly ridiculous. As Bonington noted, after watching him on Tramgo, Brown had far more than superb technical ability. He also had the boldness to go where no-one else dared. He was a master at hanging on in highly dangerous situations and patiently inserting pebbles for protection. He could break down the most demanding unclimbed lines into sections and painstakingly piece them together.

As with Cenotaph Corner, Vector is a masterpiece. But whereas, with Cenotaph, the line is painfully obvious, with Vector it's anything but obvious. Vector is three-dimensional and multi-directional. It vectors all over the place, constantly probing for the line of least resistance. It's perfectly named (courtesy of Claude Davies, who had been studying vectors for an exam). Vector seems quintessentially 1960s: an utterly stylish name, for an utterly stylish route, in arguably the most stylish decade in history. It's almost unimaginable that it could have been climbed in the 1950s. And yet the first ascent occurred a mere three months into the new decade.

Brown had thrown down the gauntlet. Any serious contender would have to repeat Vector. One by one, they came. Whillans repeated it. Crew repeated it. A young lad named Barry Brewster repeated it, allegedly in bendy boots. Many aspirants fell from the top crack. On the first ascent, Brown had uncovered a jug, then craftily replaced a sod of grass over it, to obscure it. Gamesmanship personified! Even today, with the sod of grass long gone, arms can tire, as you hang on just below, not knowing how close that comforting jug is.

The 1950s Brown-Whillans hegemony had given testpieces such as Quietus, Rasp, Erosion Groove Direct and The Thing. As with Vector, all these routes are E2. But to think of them in terms of climbing E2 today is to miss the point utterly. Pre-cams, pre-wires, what was your protection? A sling over a spike? Not many of those around! A pebble threaded, à la Brown? No certification and not so many kilonewtons, I'm guessing. How good would it be if you took a 30 foot lob onto it? In 1964 Dave Sales fell off Quietus; both runners ripped and, tragically, he died.

In his beautifully evocative autobiography 'Rope Boy', Dennis Gray mentions a climber using garage nuts for runners on Brant Direct, I believe, in the early 1960s. The poor guy was derided as 'Whitworth' and laughed off the crag. If you led VS, then the hallmark of a skilled climber, you took your life in your hands (hardly any runners). If you led Severe or V Diff, or even Diff, you still took your life in your hands (hardly any runners). Most routes were death routes to lead. Above all else, a leader had to be steady. Once people left their carefree youth, married, had families, it became increasingly difficult to muster the commitment for hard climbing.

Vector became the gold standard for hard climbing

But there were outliers (there are always outliers). From Whillans came Goliath, Sentinel Crack, Forked Lightning Crack and Carnivore Direct. From Allan Austin came High Street, Western Front and the futuristic Wall of Horrors. Sure, Austin used combined tactics on the boulder problem start of the latter. But going past the second crux, the horizontal break, solo, must have required an almost insane level of commitment.

For sheer physicality came another outlier, curiously one which would remain almost unknown for more than half a century. In 1962 Vulcan, at Tremadog, was pegged. With the pegs in place, Barry Brewster led the pitch free. Today Vulcan is regarded as a tough E4. With some of the holds probably obscured by pitons, heaven alone knows how hard it was for Brewster's ascent. F7a would be one guess. It can't have been much easier and it may well have been even harder. At least it would have been relatively safe.

In 1960 a teenage Pete Crew announced himself to the climbing world by falling off The Mincer and landing almost literally in the arms of the newly formed Alpha club. Barely had his feet touched the ground than he was proclaiming to all and sundry that his mission was to burn off Brown. Predictably this went down like the proverbial lead balloon. In the words of Al Parker, "We liked Joe..." While the Alpha males may have viewed themselves as successors to the Rock and Ice, there was still a line to be drawn.

With Vector, Brown had gone onto a seemingly unclimbable area of the crag and succeeded. He did the same on Carreg Hyll Drem ('the ugly crag'), with the superbly named Hardd ('beautiful'). He did the same (Tramgo) at Castell Cidwm, an inspired discovery by Claude Davies. And he would go on to do the same at Gogarth, with routes such as Mousetrap, Red Wall, Rat Race, Dinosaur and Winking Crack.

The greatest prize in Welsh climbing

In the early 1960s Brown made a series of attempts on the tentatively entitled 'Master's Wall' on Cloggy. Who came up with the name, I wonder – some wag in the pub or maybe an aspirant? For more than a decade, Cloggy had pretty much been Brown's personal fiefdom. Now, for the first time, he faced serious competition from a host of climbers such as Hugh Banner, Martin Boysen, Barry Brewster, Ian Campbell, Frank Cannings, Pete Crew and Dave Yates.

Famously Crew beat Brown and everyone else to the first ascent – but only by gamesmanship. If aid was needed, Brown parsimoniously allowed himself no more than a couple of points. Sure, you could peg your way up all manner of stuff - but was this a game worth playing? With a couple of points of aid, you gave yourself some leeway. Given that, back then, nearly all routes had ground-up first ascents, cleaning as you went, a couple of points of aid really weren't such a lot.

The first ascents of Great Wall (1962) and The Boldest (1963) marked the apex of Crew's climbing career. He peaked very quickly indeed, barely into his twenties. Both routes utilised what some regarded as cheating tactics: several points of aid on Great Wall and a bolt, hand-placed on lead on The Boldest. Nevertheless both routes will always stand as iconic masterpieces. As with Vector, The Boldest, a direct line on The Boulder, was exquisitely named. With Great Wall, Crew could have stayed with the original name, Master's Wall – but he didn't. Maybe he felt uneasy about the extra aid, knowing that Brown could undoubtedly have done it in this style. Maybe he didn't feel such a master after all. Maybe he felt unwilling to provoke Brown. Only two years previously, he'd vowed to burn him off. And arguably he had. But sometimes victory is accompanied by pangs of regret.

Barry Brewster had harboured ambitions for the first ascent of Great Wall. As a consolation prize, he went for the first British ascent of the North Face of the Eiger. Hit by stonefall, his dying words to his companion were heartrending: "I'm sorry, Brian..." Bonington and Whillans risked appalling stonefall to reach Brian Nally; it must have been like going through the gates of hell. Ken Wilson always reckoned that both should have received the George Cross, the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross, for their outstanding courage.

Perhaps the greatest ever Crag X

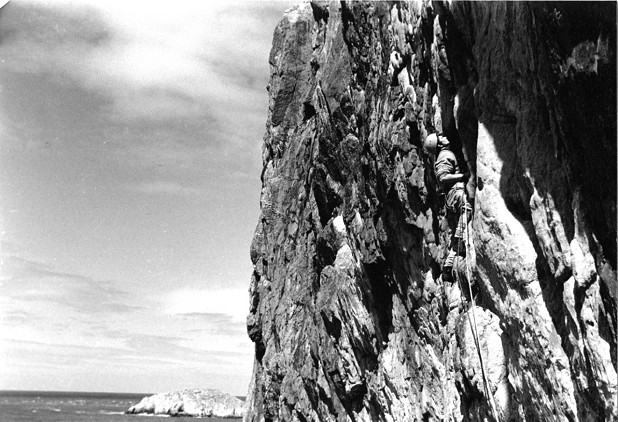

In 1964 Craig Gogarth was discovered. Sea cliff climbing was still in its infancy. A handful of routes were done and unbelievably the crag was thought to be worked out. Once again the perils of ground-up exploration were all too evident. Today the route Gogarth is an amenable E1. But when Boysen led the top pitch on the first ascent, huge, disposable flakes abounded. It must have been terrifying.

In the same year, back in the Pass, Eric Jones and Rowland Edwards beavered away, reducing the aid on Left Wall over several weekends. In the end, Rowland soloed it. Working routes is normal today; back then, it wasn't the done thing and Rowland never made any claims for his ascent. However it's only fair that, however belatedly, he should be credited both with the first free ascent and the first solo of a route which is, for many people, among the finest in Britain. Both Eric Jones and Rowland Edwards would push themselves hard over the next five decades, having adventures that most of us can only dream about.

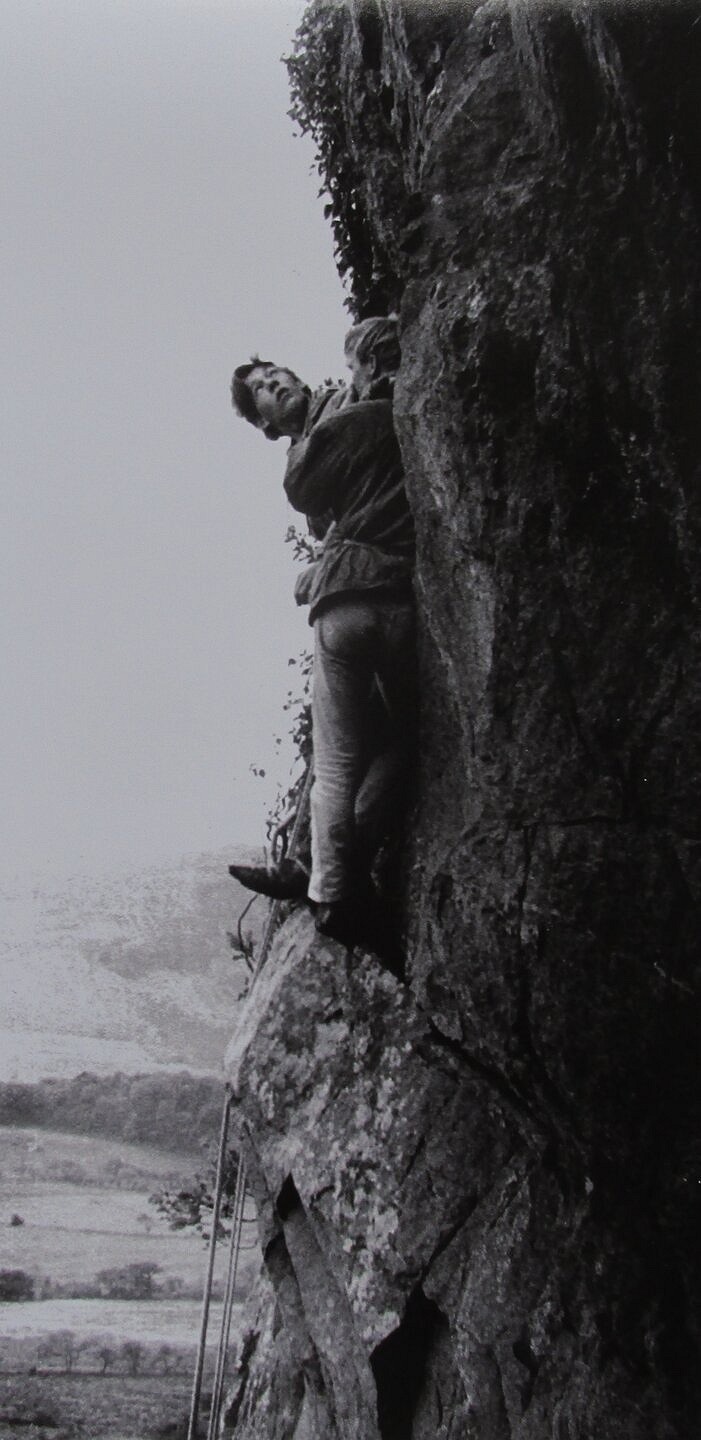

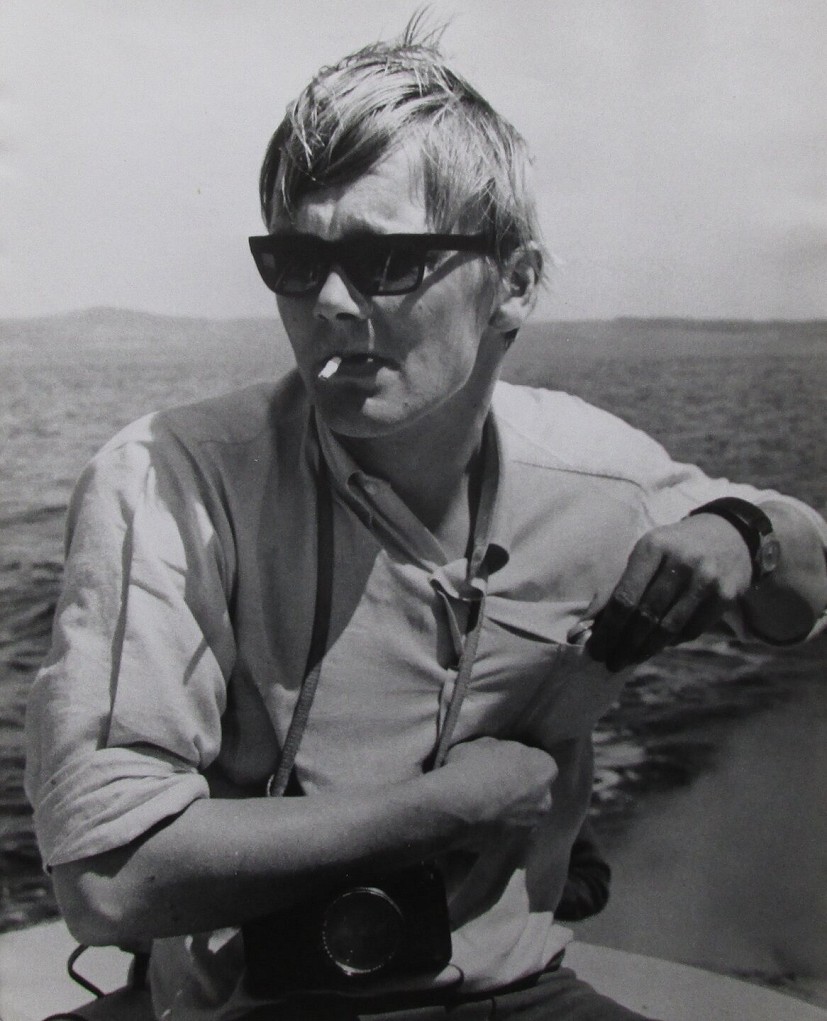

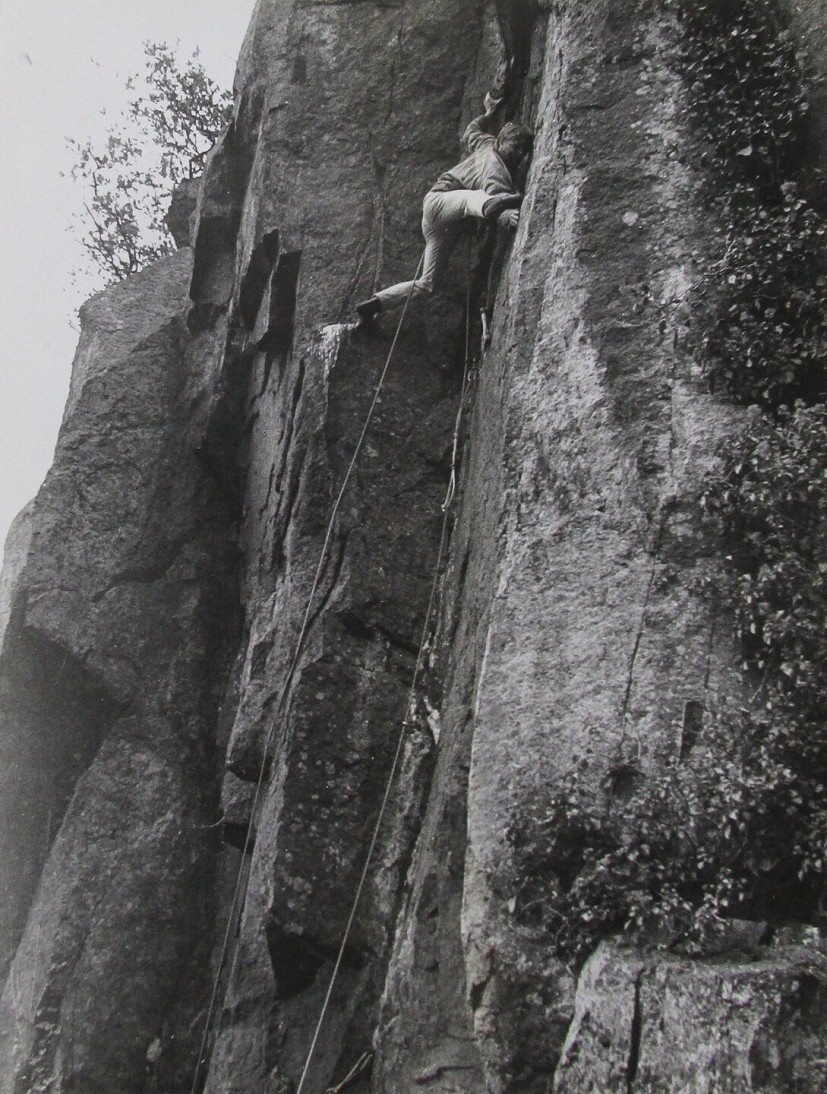

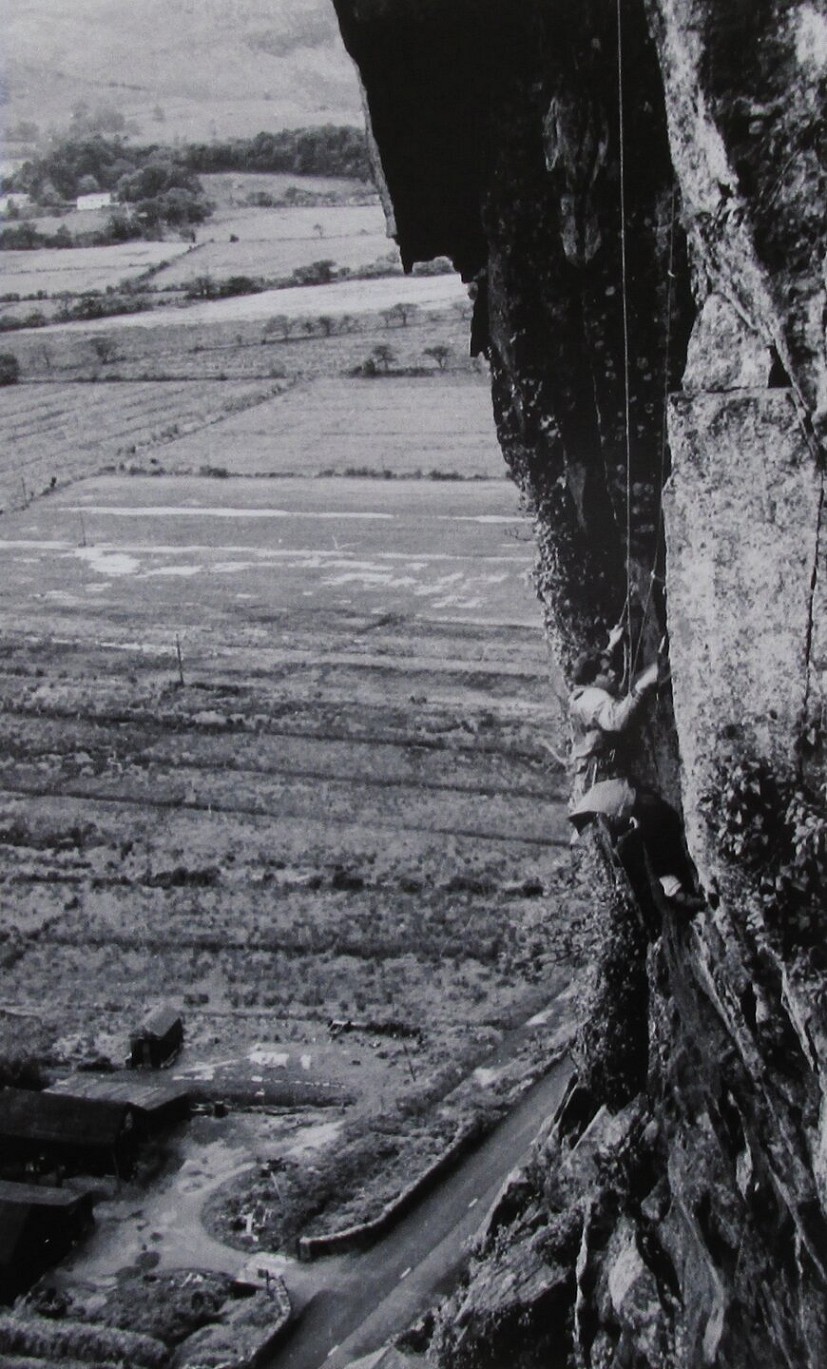

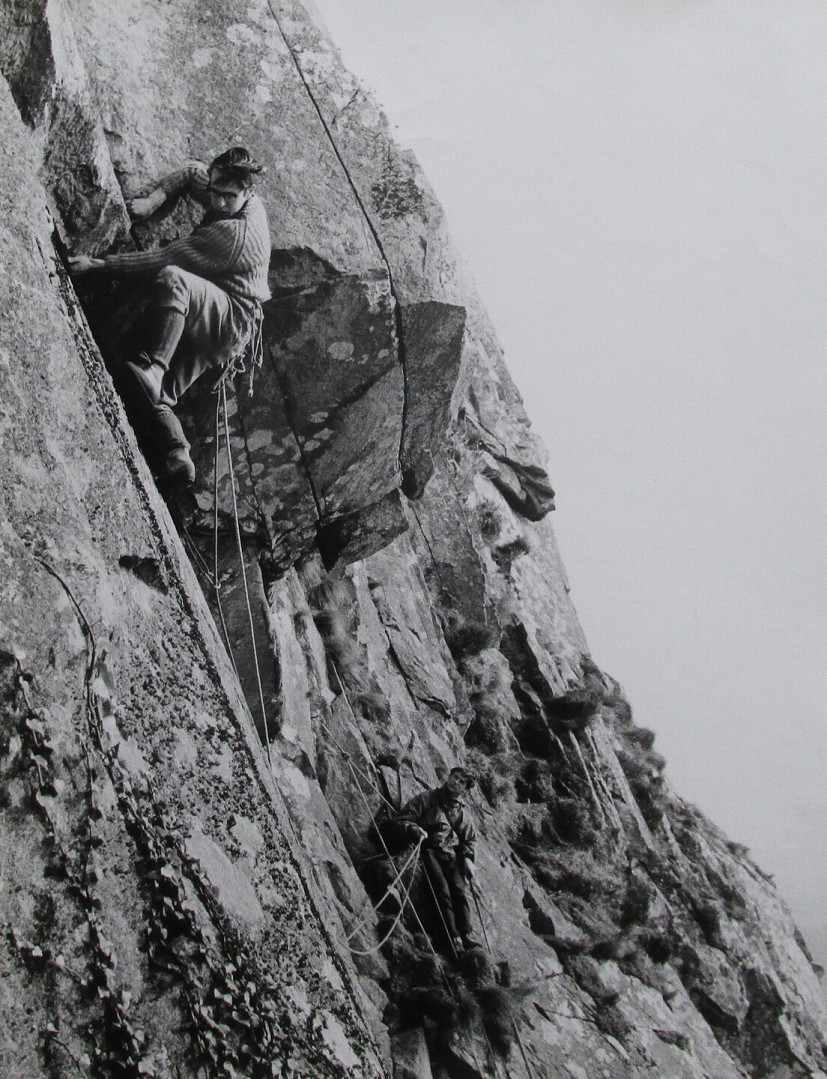

In the mid-1960s, John Cleare began taking a remarkable series of photographs of some of the leading activists of the day. The upshot was the superb 'Rock Climbers in Action in Snowdonia'. Cleare's photos have triumphantly stood the test of time. Black and white, superb composition, epiphanies of commitment. The star was a bespectacled figure in a white pullover. Although Pete Crew had passed his prime as a climber, he still enjoyed cult status.

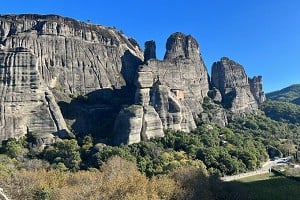

Gogarth... Crew had never quite forgotten about the place. He went back and was astounded by the range of possibilities. Gogarth became perhaps the greatest ever Crag X. The mountain crags of Snowdonia were increasingly being regarded as worked out. Maybe the future of Welsh climbing was by the sea.

Once the cat leapt out of the proverbial bag, development was fast and furious. Brown visited and, with his almost uncanny nose for undeveloped rock, found Wen Zawn. Several teams vied for the aptly named Rat Race. Famously Brown and Crew teamed up for the first ascent of the even more aptly named Dinosaur (Brown, apropos of Crew: "Long neck and no brains.") The pair were on the crag for something like ten hours on a scorching day. Tottering blocks were prised off, hurtling into the sea. Finally deeply deserved success came to 'probably the strongest team ever to set foot on rock in this country', in the words of Ken Wilson. Although considerable aid was used, going ground-up on such an intimidating and loose line was inspired. The technically much easier Mousetrap ('an instant classic') must have been almost as nerve-wracking.

New dimensions

Much as he was liked, Brown had reduced virtually all of his climbing partners to seconds (the sole exception is Whillans). And this is exactly what happened with Crew. The 'old man' became the boss. To Crew's great credit, he pushed Brown into tape-recording what became his autobiography, 'The Hard Years'.

It must have been galling for Crew. To the climbing world – and to the public generally – he had inherited Brown's crown. In reality he knew that, even with the psychological masterpieces of Great Wall and The Boldest, his routes really weren't any harder than those of the Brown-Whillans era. And by 1967 there was a vibrant new breed of even younger climbers such as Ed Drummond, Lawrie Holliwell and Tony Willmott. Holliwell made the fourth ascent of Great Wall, Drummond the fifth. Crew must have felt hopelessly trapped between generations.

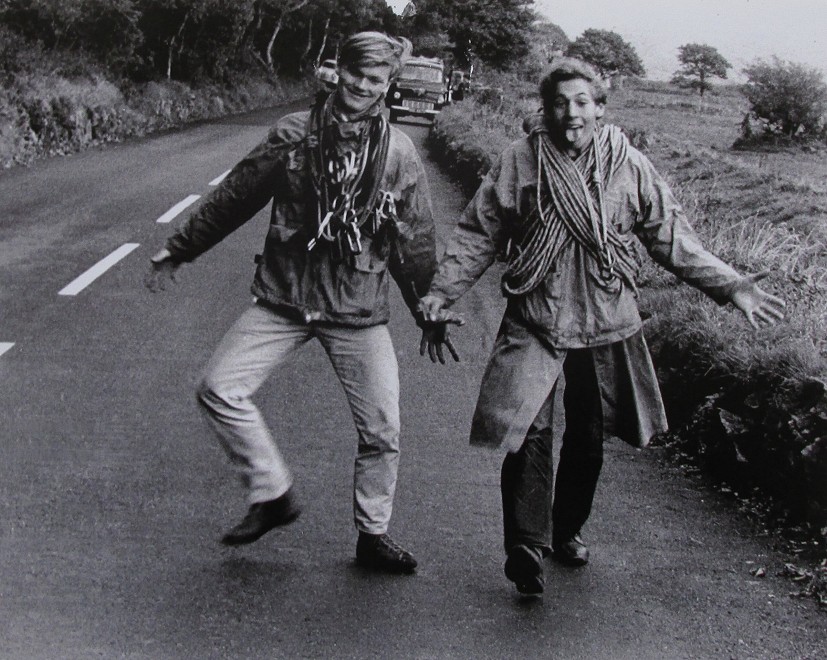

The new aspirants came from all over the country. From 1965 onwards, the then Edwin Ward-Drummond pioneered a remarkable series of new routes in the Avon Gorge. At around the same time, the Cioch club, comprising people such as Geoff Birtles, Chris Jackson, Jack Street, Al Evans and Tom Proctor were developing Stoney Middleton. Going ground-up on limestone first ascents, clearing loose rock as you went, made for bold, forceful climbers.

In 1968 Proctor and Birtles made the first ascent of Our Father at Stoney. This was the first route comparable in physicality with Brewster's Vulcan. But, unlike the pegged version of Vulcan, on Our Father protection is decidedly indifferent. With arguably F7a climbing in a highly committing situation, Our Father was almost certainly the hardest route in the country. For more than a decade afterwards, hopefuls would make the pilgrimage to Windy Ledge to attempt it. Most found themselves back on the ground again within seconds.

It was unsurprising that places such as Sheffield and London would yield strong climbers. Less obvious was the seeming backwater of Exeter, which surprisingly boasted quite a few highly capable activists in the mid-1960s. A young Pat Littlejohn rapidly went from beginner to XS leader. Together with Pete Biven, Frank Cannings and Keith Derbyshire, he went on to make adventurous explorations of many South-West sea cliffs. However, it was Cannings who grabbed the biggest prize of the day with the outrageous Dreadnought.

Back on Cloggy, yet more blankness beckoned. If Troach was possible and Great Wall was possible, then what about the space to the right of Great Wall? In 1967 the supremely bold Lancastrian climber Ray Evans made a ground-up attempt on what in 1986 would become Britain's first E9 – Indian Face. Although Evans was understandably forced to retreat, I'm sure we can all applaud outstanding audacity. Similarly Evans attempted Right Wall ground-up, before Pete Livesey's first ascent. On this occasion, he was forced back down again by his concerned second's refusal to give him any more rope!

Boldness. If you wanted to climb hard in the 1960s, you simply had to be bold. You had to be steady. You couldn't slump on a wire and shout, "Take!" One of Britain's more unstable crags is Yorkshire's Langcliffe quarry, poised above the council rubbish tip and conveniently adjacent to the local graveyard. In the foot and mouth epidemic of 1967, most crags were out of action and Langcliffe enjoyed a brief bout of popularity. A relatively unknown climber named Pete Livesey repeated the existing death routes and added another, even harder one, Sickler. At the time, Pete was caught between the competing attractions of high-standard running (years earlier, he'd come cruelly close to a four minute mile), high-standard caving, high-standard kayaking and high-standard climbing. A few years later, when he focused his formidable energies on climbing, standards would rocket.

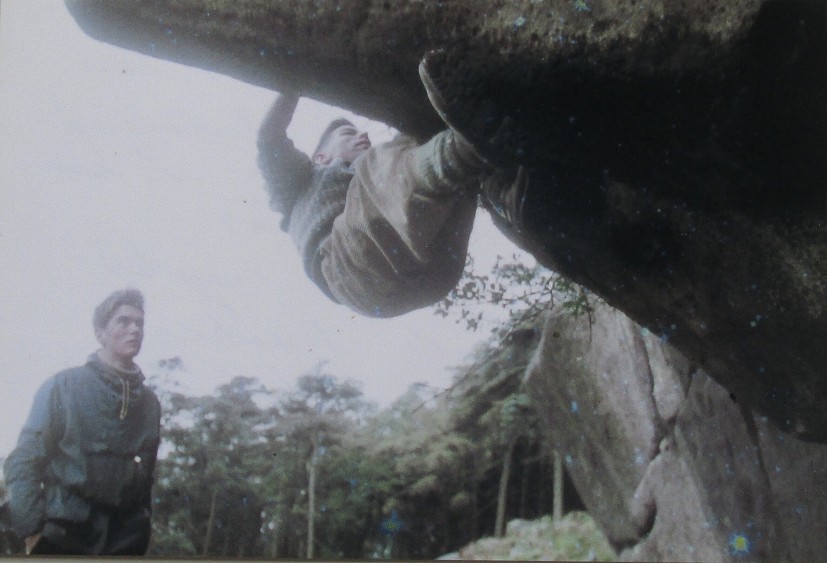

In 1968 a young Al Rouse began training on The Breck, a tiny, finger-shredding outcrop near Liverpool. A similarly aged John Syrett began training on a climbing wall in Leeds university. Tom Proctor was training on the walls of outbuildings in a Derbyshire farm. Lawrie and Les Holliwell were training on southern sandstone. Each would have been unaware of what the others were doing. In every case, the training yielded significant results.

("Anything he could lead, I could second - in winklepickers and mortar board!")

The birth of modern climbing media

In the winter of 1967, Martin Boysen, Mick Burke, Pete Crew, Peter Gillman and Dougal Haston staged an expedition to Cerro Torre. Although unsuccessful, it was an attempt to bring hard, technical climbing to a super-Alpinist environment. As such, it was well ahead of its time.

The Cerro Torre expedition coincided with the birth of modern media in climbing. Until the late 1960s, most information (e.g. about new routes) had to be gleaned from journals put out by leading clubs such as the Climbers' Club and the Fell and Rock. But suddenly there were not one but two vibrant climbing magazines. Rocksport catered for domestic rock climbing while Mountain took a worldwide view of both mountaineering and rock climbing. Mountain was edited by Crew's friend, climbing photographer Ken Wilson. Quizzing Crew on his return to Britain, Wilson was bemused to learn how slowly an all-star team had moved on Cerro Torre, versus the supposed first ascensionists, Maestri and Egger. Unsurprisingly Maestri later received the full Wilson interrogation – a harrowing experience, as some of us can attest.

Closer to home, scandal erupted in The Sunday Times with a well researched article by Peter Gillman. This alleged that a considerable number of new routes in Snowdonia were bogus. While nobody wanted to risk pushing the perpetrator over the edge, equally there was a duty to inform prospective ascensionists that these routes were almost certainly still unclimbed and the grades little more than guesswork. Televised spectaculars (e.g. the Old Man of Hoy) had brought climbing into the living rooms of the nation. Now we had climbing exposés as well.

At the end of the 1960s, there was a sense almost of ennui in the climbing world. It was well summed up in an article by court jester, Al Harris, in Rocksport. Were all the crags worked out? Was climbing in a cul de sac? One reaction was hard soloing. Both Cliff Phillips and Eric Jones excelled in soloing Extremes. (The then XS covered what's now E1, E2 and E3, together with outliers such as Our Father, E4. You took a chance on how hard your route would turn out to be.) In the event, Richard MacHardy made the coveted first solo ascent of Vector. Others, such as Ron Fawcett and Jim Perrin, would follow him. Earlier MacHardy had demonstrated his expertise with a rapid first ascent of The Vikings on Scafell – probably the hardest route in the Lakes.

(Don Whillans indulging in an impromptu spot of performance climbing coaching)

Itchy-fingered upstarts waiting in the wings...

Back in the early 1960s, poor old 'Whitworth', with his garage nuts, had been laughed off Brant Direct. But of course once a technological genie escapes from the proverbial bottle, you can never quite get it back in again. However crude by modern standards, garage nuts pre-threaded with nylon slings, could be placed with far less skill and a hell of a lot faster than Brown's pebbles. The obvious next step was machine-made nuts for climbing. Many climbers came to love MOACS and baby MOACS. For the first time ever, good runners could be placed swiftly.

Training would have an effect (e.g. Rouse, Syrett, Proctor, the Holliwells). Protection was slowly getting better. Brought together, training and better protection would take climbing out of Harris's cul de sac. But the time wasn't quite ripe.

To my mind, the 1960s Vector generation was the boldest in all of British climbing history. Climbing first and early ascents of E2s, with a dodgy runner every thirty feet, was no mean feat. Often routes were littered with loose rock. Earlier hard routes had often been easier-angled – so at least you could hang around, contemplate your fate and attempt to compose yourself. But some 1960s routes are pretty steep; back then, you really did have to go for it and failure might be distinctly painful, if not downright terminal. Although climbers in the 1970s climbed much harder, they generally had far better wire protection. And when the first cams became available in the late 1970s, many cracks became more amenable.

In 1970 Brown turned 40. Although he would carry on exploring for nearly another four decades, for him the hardest years were over. He will always be widely respected as the greatest ever British climber. Whillans had a last blast of glory on Annapurna, then faced a protracted decline. Crew drifted away from climbing, discovered archaeology and poured all of his formidable intellect, energy and focus into it.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Boysen, with his amazing talent, had seemed set for climbing stardom. Near the beginning of the next decade, he went up to Suicide Wall and, with Dave Alcock, did several new routes in a weekend. Wilson's verdict, "Go anywhere at Extreme..." was uncannily prophetic. Soon people would be going pretty much anywhere at Extreme.

In the early 1970s, Dave Cook broke the quasi-Masonic code of the dark Satanic mills with a celebrated Mountain article entitled, 'The Sombre Face of Yorkshire Climbing'. It ended with a tantalising mention of itchy-fingered upstarts waiting in the wings, biding their time, with swathes of as yet unclimbed limestone about to come within their grasp.

Dave Cook couldn't have been more right. But not all of the itchy-fingered upstarts would be content with merely changing the sombre face of Yorkshire climbing. Some had their sights set on much further horizons. Those itchy-fingered upstarts were indeed waiting in the wings, relentlessly training, knowing that their time was fast approaching. Soon not only British climbing but world climbing would be changed forever.

- IN FOCUS: Custodians of the Stone 5 Dec, 2022

- ARTICLE: Clean Climbing: The Strength to Dream 31 Oct, 2022

- ARTICLE: Thou Shalt Not Wreck the Place: Climbing, Ecology and Renewal 27 Sep, 2022

- ARTICLE: John Appleby - A Tribute 28 Mar, 2022

- ARTICLE: We Can't Leave Them - Climbing and Humanity 9 Feb, 2022

- ARTICLE: Staying Alive! Climbing and Risk 9 Jun, 2021

- FEATURE: The Stone Children - Cutting Edge Climbing in the 1970s 14 Jan, 2021

- OPINION: The Commoditisation of Climbing 2 Mar, 2020

- ARTICLE: 10 Things to Do at a Sport Crag 27 Aug, 2019

- ARTICLE: Ed Drummond (1945-2019) - A Retrospective 6 May, 2019

Comments

Another gem, Mick. Thanks!

A wonderful piece. Much appreciated Mick.

A really great article, Mick, thanks a lot. Plus I liked the Pete Crew photos, and the Zukator (E4 6b) first ascent photos

Good read that :)

That rolled back the years.