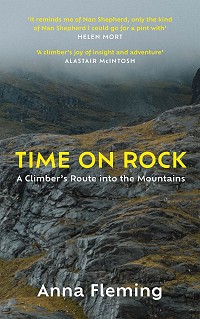

Released today (6 January), Anna Fleming's debut book Time on Rock: A Climber's Route into the Mountains, published by Canongate, is a story of a young woman's climbing apprenticeship with a socio-cultural and geological bent. Anna's ten-year climbing journey takes her from a dusty indoor wall in Liverpool to the gritstone outcrops, Welsh slate, Lake District rhyolite, Moray sandstone, Cuillin gabbro, Cairngorm granite and Kalymnian limestone. It's an adventurous coming-of-age tale in part, but Anna's scope in Time on Rock is also far broader.

Each rock type has a unique character which influences not only the way we climb on its surface, but also shapes our ambitions, fears and the stories we tell over pints in the pub, Anna discovers. She deftly describes the physical and mental challenge of climbing in a manner that is accessible and compelling to both climbers and non-climbers—no easy task.

Anna also writes openly about the challenges of climbing as a woman in a male-dominated sport (managing contraception and climbing performance throughout the hormonal cycle, anyone?), helping to balance out the lack of female perspectives in mountain literature.

'An affinity for rock develops slowly. It is not something you can easily pin down, explain or quantify. It is an embodied knowledge, acquired through craft, care and practice. It is a relationship that is constantly evolving, developing and changing. In the process, for better or worse, the medium becomes engrained into your being. We shape the rock, the rock shapes us.'

Helen Mort's cover quote is both high praise and on point: "It reminds me of Nan Shepherd, only the kind of Nan Shepherd I could go for a pint with."

Anna is a Welsh writer, Mountain Leader and PhD graduate based in Edinburgh. I shared a conversation with Anna about climbing, geology, culture, history and found out what her time on rock has taught her about the natural world and her own identity as a climber, woman and human being...

"That's what good climbing means to me, finding that very deep connection to the earth and to the landscape and feeling it and performing it within your own body."

You write that your family occasionally went walking and were slightly outdoorsy, but that they didn't understand climbing. You started climbing in an indoor setting. When you were climbing indoors, what attracted you to the sport?

Indoors, I love that process of working up the wall, pulling your way up holds and connecting physical sequences. There's that amazing rush of achievement when you complete a route. I love the physical movement of it, of being so intensely in your body working out how to map your body onto the climb. I also like the sociability of it. Everyone wants to chat and you can make great friends. That was initially what pulled me into indoor climbing and it feels a lot safer than when you're climbing outdoors. It's a nice entry point because there's less to manage; you're not getting cold, you're not on a rock face. It makes climbing accessible in the way that going swimming in an indoor swimming pool is lovely, but out in the sea or in a river is quite a different experience.

After your indoor apprenticeship, you moved on to the gritstone. You talk about it being almost like learning a language and having to get to grips with this weird rock type. What did you learn from climbing the grit?

Grit is an interesting rock type to learn on. It's difficult because it's so technical — a baptism of fire — you've got to get those techniques nailed in terms of 'Here's a blank slab, there's a tiny little pebble...can you hold your balance and your nerve and keep going through it?' Suddenly you're inside a very sketchy chimney or squirm hole that's apparently only graded Severe and you're like, 'Oh my god, I can't get up through this!' As a new climber I was very grade-oriented and thought about climbs in terms of how difficult they were and what I thought I should be doing, so to then get outside onto gritstone and essentially have my ass handed to me many, many times made for a very sobering learning experience!

I don't love grit, but I'm glad to have spent that time on it and I would still go back for another week of having whatever strange epics you have on those 10 metre walls. It teaches you about technique and how strangely difficult rock can be compared to indoors.

Grit was where I learned how particular that niche outdoor climbing subculture is, which is so different from indoors and hillwalking. That was where I first understood how all these routes have got names, histories and dates attached to them. There are people working through them and developing that continuity over the years of people climbing them and then you'd meet the older climbers — who are totally battle-scarred — and they'd show you all the damage they've done to their hands over the years and be so proud. I thought that was something special about this particular rock, which is just bloody difficult and short and weird. It has such a strong presence within climbing subculture. It's an interesting entry point to the world of rock climbing and it's very British. Yeah, very, very British!

The book showcases the variety of rock types and climbing styles in the UK. Kalymnos is an outlier geographically, but you talk a lot in that chapter about risk and how non-climbers see it as a dangerous sport. You write that climbing 'provides a good space to continue exploring risk as an adult' following on from learning to take risks as children. 'Failing can be difficult. The emotions of failure are hard to stomach. But the best climbs are those where the outcome is uncertain [...] A good climber does not eliminate risk: they harness its electrifying charge.' How was it for you to get this across to a non-climbing audience?

Having come from a non-climbing family I sometimes envy people whose parents are climbers, because I can see that they've been brought up with a level of comfort around the risks of climbing. They have an ease that's handed to them from their parents who've been through that process. My family don't really like climbing and they've always been concerned for me. The mainstream media perspective on climbing hones in on how dangerous it is. When you start, especially outdoors, you internalise all those mainstream cultural perspectives on climbing that tell you it's very dangerous and it's for all these adrenaline junkies. The mainstream media groups all climbing together; from gritstone climbers to Himalayan adventurers. It's only as you start to find your way in that you realise there are very different types of climbing experience.

Learning to push myself in climbing is so engaging and that's the same for all climbers at every level of ability. You can be a V Diff climber or an E11 climber and you essentially get the same experience when you push yourself out of your comfort zone. That's where you weigh up all of the balances and try to get into that zone where you are comfortable pushing yourself that bit harder. One of the things that's exciting about climbing is working towards that place and achieving that and then coming back into your comfort zone later on.

A bit further on in the chapter you talk about gendered ideas of risk and how people don't encourage women to take risks in the same way that they might encourage boys. You — like many women — are often told to "Be careful!", which makes it a lot harder to break out of that comfort zone. Can you elaborate on this?

It's something that I experienced, but I don't know whether that's true for all women. Now that we're getting more women coming into the sport, we're able to hear more women's perspectives on things. Since I didn't know a lot of women climbers and mostly climbed with men, that makes for a very different experience in terms of how you feel about risk and when I'm pushing my limits I'm definitely very aware of that social pressure from all the people around me who might not like me doing this, who might think that I shouldn't be there, that I shouldn't be up on that wall, that I shouldn't be pushing out of that zone. I don't know whether men have that same experience, that sense of social pressure meeting them on the wall or not?

'I had imported a set of cruel binaries and constructed a tight-fitting corset for myself, telling myself I couldn't climb as well as my male friends because I was a girl.'

The physical differences between men and women made you feel inferior to male climbers, but in Kalymnos you realised for the first time that women can climb just as well as men. Climbing walls can be very performance-oriented and set by men for men, you write, but in Greece you learned that there was a more level playing field outdoors. What was going through your mind there?

I was bouldering a lot in Leeds and had learned climbing from men and with men. Whenever I struggled, I watched men do the moves, and since they showed me how to do things I felt that men were better than me. If I wanted to know how to do something better, I would watch a man. Going to Kalymnos and climbing beside women who were streets ahead of everyone was totally transformational.

Seeing other women climbing helps me dream my body into new spots on the rock: 'Oh, other women whose bodies look like mine, who have periods and have hormone cycles...they have the same physiology that marks us apart from men and yet they're still able to go up and do those amazing things!' That was a powerful moment and I find the changes that I've seen in climbing since I started in around 2008 exciting. It felt like a different world to what it is today in terms of indoor climbing. Back then it was still male-dominated and it's now reaching 50/50 and outdoors is slowly catching up. In this book I want to encourage more women that trad climbing can be for you and yes it's scary, but that's OK. Meeting your fear on the rock is not a bad thing. You just keep trying and have another go. Gradually you'll get more comfortable with it and that's fine.

You also talk a lot in that chapter about mindset, the differences between Chris Sharma and Adam Ondra's approach and differences between men and women and how we try to take on other people's mindsets. What did you learn on that trip about your own mindset and how was that developing as you were climbing?

When I was in Kalymnos, I was keen to push myself and climb harder in that high energy, high desire climbing space. I was coming up against mindset troubles in terms of moving above bolts and suddenly facing that fear of run-outs, which, having done a lot more trad now, I'm like, 'Well, bolts are a bit more chilled-out!' I was thinking about mindset because I'd reached a certain level of technical ability and physical strength. It was around that time that I read The Rock Warrior's Way, which I found helpful. I was finding the head game challenging and I feel like that is more troublesome for women. I know a lot of competent women who find it more difficult to lead climb, but notice many men who are far more comfortable leading and taking falls. I was thinking about physiology and asking, 'Oh, is that testosterone at work and something that I'm missing... because it would be nice to have more of that!'

Luke, whom we were climbing with, had been climbing for 20 years and so his technique was excellent. He was pushing a different mindset. We had been entering that aggressive battle mode, which I've written about on the gritstone, which quite often is this 'fighting' rock. Similarly on Kalymnos I was seeing it as a battle — you go up, you fight and you chase for victory. Trying to switch into a much calmer headspace was the goal that I suddenly discovered on Kalymnos; rather than trying to charge and fight to the top of the route, it was more about slowing down and thinking through everything and occupying a calmer, meditative strategic state on the rock. It was exciting and fun to explore that, although it is more challenging to try and adopt a new mindset compared to learning a different set of moves.

You write about hormone cycles and how many women (and men!) are only just starting to talk about hormones in the context of sport and how it affects their performance, both mentally and physically. Is the taboo lifting in climbing, do you think?

Many women are now tracking their cycles. Previously, you would track your cycle if you were trying to get pregnant. Now those who aren't trying to get pregnant are still tracking their cycles and keeping an eye on those changes. It's important in that high performance space and if you're trying to push your grades and climb hard and you've got an intensive training schedule, you need to work with your physiology in terms of how well your body's performing, what kind of headspace you're in and knowing when to back off and take it easy and when to push. Even if you're not in such a high intensity training schedule, tracking can be useful to let yourself off when you're having those tough weeks when you're suddenly like: 'Oh, my goodness, why can't I tie this knot? What is going on? Oh, I'm premenstrual, that's fine.' The climbing community is becoming more open to talking about these issues and it's been really nice to see this shift in perspective.

Moving on to the Cuillin, you talk about how time on rock can feel 'boundless, fathomless, infinite' and how when you were climbing your sense of time just faded away. 'I stumbled into the most extreme geological disruption of time.' How did you experience that in the Cuillin?

The intensity of focus in climbing melts time. I always got completely lost in it, especially in my earlier, less experienced days. I had no idea of how long things took and it would seem like you'd hardly covered any ground at all, but then you'd check the time and several hours had passed or suddenly it was getting dark.

When you're moving closely across small details and focusing so intensely on them, you slip into a different time zone. I love that about climbing. It can be terrifying when suddenly it's dark and you're in the wrong spot. But it also feels like such a privilege to be able to give yourself that much to the mountain and to get completely lost inside an experience like that.

When you lived in the Lake District, you didn't have access to indoor walls and you were completely immersed in the outdoors. You had to spend even more time on rock. Living there 'paved the way for a different relationship to landscape and climbing than I had known before.' You write that your legs 'soon fashioned a new muscular familiarity with the landscape' as you built your 'own map' of the well-trodden area. You also met the Birketts and the drystone wallers. In which ways did the Lakes give you new perspectives on landscape and how people interact with rock and the environment?

In the Lake District I got my first sense of what environmental climbing could look like. Instead of being about performance, sports, grades and pushing yourself, climbing could be an immersive environmental practice, a way of being in the landscape, of getting to know the texture of a place and how it feels to inhabit the landscape in a place where many layers of nature and culture meet and mingle. I saw this from spending time with the locals who have such an affinity to their place. We'd meet in the pub and and their stories were never about gear, grades or performance. They were not interested in that.

Rock plays a central part in the connection to their home. The Birketts and wallers always handle it so well with strength and dexterity within their bodies, within their hands, within their minds, which is something I recognised from my own dad because he's a builder and manual labourer. Being able to visualise something and then physically manifest it was something that I saw from my dad and then here in those climbers and wallers. They could see these stones and put them together into a wall or they could look at a rock face and see the routes and the way that their body would move through it all to make that route exist. I saw a very different way of relating to environments and working with rock as a material that you could produce some kind of art with.

When you returned to the Cuillin, you write that you had completed something much bigger than the Cuillin itself; you had tested your body and 'it had performed the piece.' How different did you feel in yourself when you returned?

Worlds apart. The first time I went to the Cuillin, I was in my early 20s and was completely out of my depth. I was terrified of the routes, the rock, the exposure. Returning, I expected to find it as challenging as that again, so it was a real shock to go back and discover that those things weren't an issue anymore. I find it exciting and engaging to be able to work with such an amazing, massive piece of rock. Suddenly route finding was fun, picking your way through all those narrow edges and teetering along the little ledges and keeping yourself in balance and trying to sniff out the line. It brought this amazing sense of exploration and adventure. I realised more of what I learned from the Lake District, of how climbing can be that artistic embodiment of a landscape and how you're working with the forms that are there and performing them through your body and that can be a beautiful dance or performance on the face.

The Dinorwic chapter was one of my favourites. I could tell that the place was special to you as a Welsh woman and it was very moving in the way that you write about the extraction of the rock and the exploitation of the rock and the people as well, the slate miners who had tough lives. What was that chapter like for you to write?

It was different to writing the other chapters because the others centre on natural landscapes. Dinorwic was the only industrial or post-industrial landscape that I wrote about in a lot of detail. It's an emotional chapter, which was partly about connecting to Wales and exploring that sense of Welshness and the relationship between Welsh identity and landscape and place and that experience of extraction and exploitation, which happened to people and the landscape.

Dinorwic is fascinating. It's so huge, it's mind boggling; beautiful and disturbing. With all the old metal, loose slate and broken staircases there's a sense of waste and decay – a place left behind to rot, but then the quarry is also so immense and beautiful and is full of gorgeous slabs.

So those two things are held in contrast while the history is also present. Climbing on those edges, you become aware of the people who made them – you're climbing a face that has been made by fathers, sons, brothers, uncles from this local area, many of whom died young from lung disease. The scale of suffering sits alongside the scale of achievement. That human aspect of the Welsh culture and pride was interesting to explore. I wanted to celebrate those men and their achievements.

I was interested to read about your grandmother, who was 'a Lancashire woman with a passion for words and language.' Did your grandmother influence your writing?

My grandmother loved writing, she was a literary woman. She went to university in Manchester and studied English Lit. She had a viva at the end and she was examined by Tolkien. She said she absolutely hated him after it as he was sexist and gave her a hard time. So yeah, the family don't like Tolkien!

She used to appear on Woman's Hour and write articles. She never had any books published, but she created this strong literary family and we take real delight in words and language and quoting things. On her deathbed, as her mind was shutting down, she was quoting Shakespeare. From her, I got a sense of the importance of words and language and that definitely passed down through us all and we're one of those families that love an anecdote, love telling stories. So for me, that's why one of the things I love about climbing culture is that oral storytelling aspect; "We've had a bad day, but let me give you the story!"

You explain how climbing helps to forge profound bonds between very different people. You write about the quarrymen working together and climbers working together. Throughout the book, you're forming friendships and social bonds with the people that you're on trips with. You also talk about how climbing can form very strong, intimate but platonic bonds between the sexes. Is this something that makes climbing special for you?

I love the friendships you develop through climbing; deep friendships where you go through challenging experiences, where many people would just say, "Absolutely not, I'm not doing that!." It's quite a particular group of people that you're working with and those who are good to work with in those spaces become real close friends and allies. I value that cross-gender mixing. I've never been interested in doing all-women events, or only climbing with men — I just love having a mix of people to spend time with.

'That's one of the things that I love about climbing. in the unforgiving vertical regions is that there's no room for bluff, bluster or pretence. On the rock face, the veneer is stripped away and you can see the heart and mettle of a person.'

That's one of the things that's so special about climbing, you can have those close working friendships with men and it doesn't need to be about sex. You've got a shared ground, you've got this thing that you're working on together and you can both respect each other for doing that. That's on an individual friendship basis, but there's also the wider community and that sense of belonging to climbing culture and this climbing community is something special. Once you're a climber, you're part of this community and you've got this shared language and these shared experiences that people are so excited to share, such as what a climb was like: "What the hell are you talking about? Why are you so excited about weather and bits of rock?" I love the absurdity and obsession and the intensity of it.

Most of the book is about your journey as a climber, but in the Moray sandstone chapter, you get a bit more personal, writing about a relationship breakup and how you threw yourself into climbing as a way to clear your head and to have something to focus on. How did climbing help you grow personally?

Climbing was amazing at that time. I was so sad after that breakup. It was raw and there was a lot of grief and pain, but climbing lifted me out of that. I would go climbing and feel horrendous before and horrendous afterwards, but on the route, while moving on rock, I felt better. It was partly to get out and socialise and see people and it was partly that I was just doing physical exercise, which helps. But there was something about the immersive intensity of the focus of climbing that helped and through that experience, my climbing transformed. That was a real shift for me in terms of my headspace. I suddenly became much calmer and more focused on the rock. The grief stripped a lot of things from me and in that raw state, climbing was everything.

I was conscious that quite often women get into climbing through a relationship — and then what happens if that relationship ends? If the man has taught her and the man has the gear, the woman can stop climbing. That was part of my determination through that breakup as well, to say: "I'm still going to keep going climbing. I'm still doing it — I love it and I'm going to keep climbing without a man."

In the Moray chapter you make connections between pilgrimage and climbing and the Bronze and Iron Age people who lived in or visited these caves inside the sandstone. You write about how 'distinct realms' open up when you're inside or engaged on bodies of rock. Do you think climbing is comparable to a religious practice in some ways?

It can have a religious element. There's something about that practice of going to the rock every week and being present there and trying routes. We are living in an atheist time when we don't have spiritual wisdom. What we do have is a lot of consumerism and materialism and capitalism, so finding those places where you can get deeper meaning and find a connection to something that goes beyond the present moment and your consumer self is important and that's one of the things that climbing gives to me — that moment where you can connect with very different times through the rock's geological history, however many millions of years ago when it was formed deep within the earth and then its future. It gives you that sense of being in that very different scale of time rather than just dwelling in your everyday concerns.

There's also the cultural human history of rock; connecting with climbers from the present and in the future. If you're making new routes, you're making routes for the future. You're setting a new cultural piece. You're also connecting with all those people who've gone before, you're putting your hands on something that someone else touched last week or years ago, and you've all collectively put that polish on it. You're connecting with that climbing culture and that history as well. But you can also connect with that much deeper, older human history and culture from before climbing times, such as quarrying rock to build houses, or caves that have been used for some kind of ritual practice, which links back to a religious group I witnessed in Yorkshire, where priests sang into the gritstone. There's something intriguing about the rituals of going to these rocks that exist far longer than we do, bringing our practices to them and our practices marking them with scratches or graffiti.

Both your approach to landscapes and your writing are inspired by Nan Shepherd. You mention reading Shepherd in a café in Liverpool. How much did she influence your thoughts and how you see the environment?

Nan Shepherd was a game changer for me. It was so important to read her work. I knew Wordsworth's work through my PhD and read him first. Then I read Nan Shepherd, who was influenced by his writing. There's that continuity and what I loved about her was that she was a woman, so I could read about a woman having these environmental insights and relationships with the mountains and walking in them and I could relate to her because it was another woman writing. It was amazing to discover a woman who had that philosophical insight into the mountains and she was a role model and a guide for me throughout my 20s from that first reading in Liverpool, when I was starting to think about relationships to mountains, to when I was living in the Cairngorms and walking among her hills. I was spending a lot of time on my own walking into the mountains and that could get boring and lonely, but I took her with me in my head and spirit.

Shepherd sees the mountains very differently to someone with the goal-oriented perspective of personal bests and reaching the summit; once you've done all the tops, what else is there to do? You could think 'Oh, I must go to a new area and do all the tops there!' or 'Do I need to try and beat my personal best?' Shepherd gave me a different way of being in the mountains that you could enjoy by opening up your senses and lingering there and exploring the place in different weathers. Each time you'd go into the mountain you'd be experiencing it in a different way; you would see something new, your body would feel different. Your internal weather would be different, and so would the external weather be. Shepherd taught me to open myself up to those subtleties of experience and to chase that richer depth rather than going harder, better or faster.

The finale in the Dubh Loch is a fitting end to the narrative arc from your indoor initiation and cutting your teeth on gritstone to climbing Cayman E2 5c. Tell us how everything came together on that mountain route. How were you feeling?

I was nervous beforehand. I ran across the route in my mind and tried to anticipate what might be there. The two sides of the coin were in balance; the nervousness and the excitement. That's the magic of a good performance, whether in climbing or a job interview or on stage; there's that narrow window where nerves and excitement come together and it all works. The Dubh Loch is a magical place and there's such a long walk-in through the environment. You're in the place in that Nan Shepherd way of walking through and immersing yourself in it, filling your water bottle up from the burns, drinking from the mountain and you're becoming part of the place before you even get onto the rock. When you look up, it's an enormous face. The level of unknown was high because Cayman is such a seldom-climbed route. I was starting at the extreme end of Dubh Loch esoterica! There was an intimidation factor but also a sense of being part of the place, by coming in and getting on the rock and working well in a strong partnership, with both of us having that Shepherd approach to mountains.

We were of one mind when it came to the climbing, working up the line and entering into the rock while managing early-doors nervousness, thinking: 'Oh gosh, that's one pitch and we've only got nine more to go!' But discovering the rock on those ten pitches pulls you into a very different headspace compared to being on a short gritstone edge. This mountain of rock demands that if you're going to complete this route in good time and form, you need to crack on, bring your best and just do it. It brought out the best in our climbing. Then you move into fatigue, which is a special part of climbing. When you're so tired, that environmental perspective softens it a bit; you're experiencing how the place makes you feel, how exhausting it is but also how special it is and why it's worth it. Then you complete the climb and you've still got a long way to go, to walk out through the darkness with the stars coming out and the stags roaring.

It seems that by the end of your journey, you've not only become fluent in rock climbing movement, but you've also gained a deeper understanding of and appreciation for the outdoor environment and people's connection to place. How would you sum up your 'Time on Rock'?

That sense of fluency with the rock is like learning to speak the language of rock. In writing this book, I revisited many rock types and put my head inside those rocks again to remember how they worked, trying to capture that rhythm of different movement styles on different rock types. From the slate with its sharp, precise edges and no friction to the gritstone, where you eye your way up and turn your body into a hold.

In the book, I explore the fluency of working with different rock types, which I see as a builder-climber practical mindset of how to handle a particular rock type, complemented by the Nan Shepherd, artistic and environmental perspective with its holistic, embodied way of being in a landscape and familiarising yourself with and putting yourself in the place. That's what good climbing means to me, finding that very deep connection to the earth and to the landscape and feeling it and performing it within your own body.

Read Anna's blog The Granite Sea. Follow Anna on Twitter and look out for her upcoming book tour dates across the UK.

- SKILLS: Top Tips for Learning to Sport Climb Outdoors 22 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

Comments

Fascinating interview. What wonderful highways and byways there are in climbing! I've added it to my books-to-buy list.

I accidentally tuned into an interview with her on R5 and my journey flew by ! I kept waiting for her to to tripped up by the stock media questions and every time she came back with a well considered answer I could pretty well relate to.

Here is the interview. Starts just after 2 hours: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m00132n6

I thought it was very good from both the interviewer and from Anna.

Amazing piece.

Great interview, very much looking forward to attending the book launch in Edinburgh on the 14th (tickets still available!) and reading the book.