Chris Shepherd writes about climbing on the spectrum and how the sport has helped them to lean into their difference, rather than conceal it entirely.

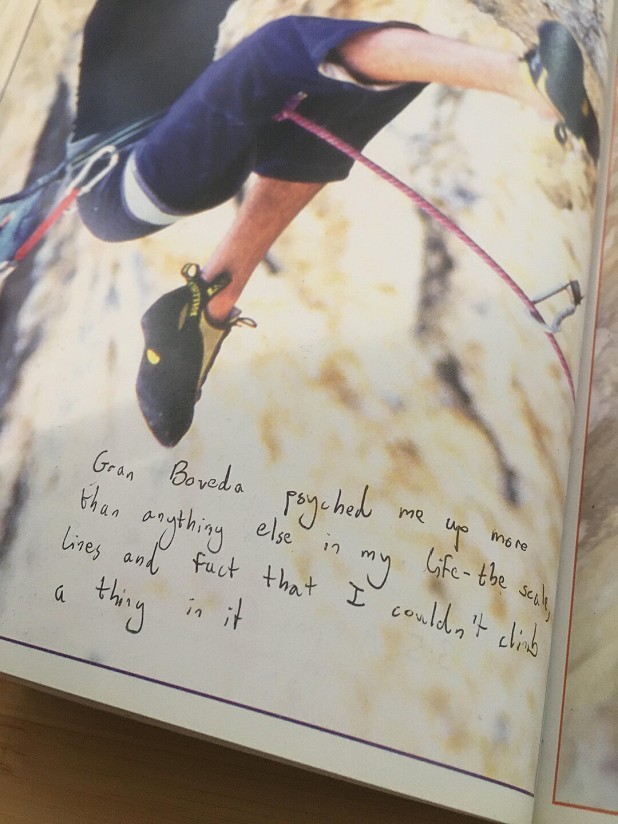

It's a busy Saturday at the Cheedale Cornice and, as in so many other instances, I know exactly how my day will unfold. After a quick hello to the regulars, it's back to the project - one route to the right of the previous fixation - quickdraws in, shoes on, tie in, carefully inspect and practise the moves.

While working the crux sequence, I notice that by flicking my right hand into a previously-unused undercut before a strenuous clip, my hips come out and the position becomes slightly more stable. Elated, I thoroughly brush all the holds, preparing for my next time up, and gush about this progress to anyone in my line of fire. This incremental progress, realised through extensive repetition and subtle variation, floods my system with dopamine to an extent that general society may find perplexing: my day has been made and I may well be back tomorrow for more of the same.

My name's Chris (they/them), I'm autistic, and the opener above was my rough attempt at describing the sensations of pursuing climbing as a special interest - an intense and highly-focused passion, which is a key aspect of many autistic people's experience. However, this paragraph is also a cliché, and you've probably read recollections like it countless times before. The question I therefore pose to you is, given that only around 2% of the general population is estimated to be on the autism spectrum, why does this account feel so familiar?

In this article, I'd like to suggest that climbing and autism enjoy a unique relationship, beyond that of a typical special interest, and that climbing provides autistic people with a route to a more social and colourful existence. Because everyone's experience of autism is unique, and I'd rather not speak on anyone else's behalf, I'll be using my own experiences as an example. I'll finish with some of my own gentle suggestions, for autistic people and allies, with a view to make our community as inclusive as possible for everyone's benefit.

What is the autism spectrum?

I guess we should start with the unavoidable slab of definitions. Autistic people are born with a developmental neurological anomaly with many possible causes, which affects how they communicate and engage with the world. They may have difficulties understanding how others - and sometimes themselves - feel, in processing nonverbal communication and when picking up on behavioural norms.

Autistic people may be more sensitive than the statistical average to stimuli such as bright light and loud noises, and find the uncertainty of new environments and experiences to be highly anxiety-inducing. The autistic spectrum ranges from those who require full-time care, to those who can fully "mask" their differences within general society, with the latter being common among women and people raised as female.

You may have heard mild-to-moderate autism described as Asperger's syndrome, a term which, in addition to presuming that autism is a disorder, is tied to the Nazi eugenics program. This term is also considered somewhat redundant, so I'm going to avoid this term entirely, instead using the term "autistic" to describe anyone on the spectrum. Autism is included within the broader category of neurodiversity, which encompasses non-standard neurological and behavioural patterns, including ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity "disorder"), dyslexia, dyspraxia and several other variations.

This is all quite formal and frames these conditions as disabilities - which isn't necessarily true - so let's humanise it. I like to think of people as having a Dungeons & Dragons-esque character sheet with different areas of their personality receiving points, which can be levelled up by work, but from an unequal base depending on one's player class.

Compared to the rest of society, autistic people's "socialising" stats are somewhat dialled down to varying degrees, and their character points have been pumped into the "logic", "focus" and "determination" skill areas. This leads to a highly-tuned individual, and of course I'm using the analogy of a spell-casting character - I'm describing myself as a wizard and there's nothing you can do about it.

Just as a spell-casting type has to step back during mundane battles, only later to wipe the floor with magic-sensitive foes, autistic people can excel at specific tasks* and make enormously positive contributions to society. For example, in addition to the legacy of autistic people excelling as artists, mathematicians, musicians and scientists, curveball examples also abound. For example, openly autistic Greta Thunberg is spearheading radical climate action in young people, recently-diagnosed actor Anthony Hopkins is regarded as a national treasure, the list goes on.**

Getting back to the topic at hand, which is still apparently climbing - I don't know how that happened either - world-class wad and newly "diagnosed" autistic person Paul Robinson sustains a near-unfathomable climbing output, having climbed over 1000 boulder problems graded 8A or harder.

* Although they absolutely do not have to excel at anything in order to be valid

** We don't talk about Elon Musk around here.

Special interests

It's no great secret that, in the face of a sensory and behaviourally confusing daily life, many autistic people like to invest their energy in a narrow set of interests, pursuing them to an extent that may appear excessive to neurotypical people. The role of these interests as an output for autistic people's passion and determination seems to be crucial - studies place the proportion of autistic people with special interests as high as 75 to 95 percent.

Autistic people may partake in lofty pursuits such as art, music or science, but may also choose quieter pursuits such as collecting records or trainspotting. Whatever the interest, they tend to be pursued with an abnormal degree of repetition, and can lead to extensive expertise in a particular area.

All of this is par for the course amongst climbers, who are unshakably keen to visit the same piece of rock for years, showing up with an assortment of small brushes to meticulously prepare their environment for the Redpoint Go. Combine this behaviour with the meticulous logging of activity in guidebooks, and the soaking up of technical skills, training knowledge and the like, and in my opinion it's fairly clear that climbing is pretty autistic. I'd go as far to say that the special-interest aspect of climbing is among its most celebrated elements, and the community treats its most focused and dedicated practitioners with a special reverence.

This stands in stark contrast to the guilt-ridden upbringings of some autistic people, who were taught that their powerful desire to pursue their passions was selfish or even malicious, a symptom of a spoiled or maladjusted child. Personally, the label "obsessive" was a label that was often used against me, and I've benefited greatly from the climbing community's reclaiming of this term as a positive attribute.

In my opinion, this reflects a community which supports the harnessing of autistic people's focus, allowing them to achieve incredible feats, to feel fulfilled and rewarded for being their authentic, brilliant selves - all of which segues neatly into my next point.

Social conventions and social groups

If I were to ask you, "How do people on the autism spectrum interact with others?", what kind of behaviours would you describe? Unfortunately, I think there's a significant chance you might picture an obnoxious and scheming personality who manipulates those around them, influenced by the fact that the most familiar autistic character in popular culture is physicist Sheldon Cooper in that god-awful TV show (The Big Bang Theory). You're also probably picturing a cisgender man, but we'll get onto that soon enough. You might imagine that autistic people are incapable of learning even the most basic social skills, making them vulnerable to pity and ridicule.

However, many autistic people are adept at learning implicit social behaviours by processing them in an explicit way. This helps autistic people to "mask" - appear neurotypical - in society but can be extremely draining. The cognitive load of masking may lead to so-called shutdowns and meltdowns, which describe the loss of high-level functioning and speech control through the "freeze" and "fight" involuntary responses respectively.

With my sample size of one, I can confidently say that at least one autistic person finds that the high-level processing required to mask day-to-day leaves them with little energy left for free-time social interactions. As a result, many autistic people experience feelings of social isolation and loneliness, with as many as one half to two thirds of this population having no close friendships whatsoever.

With this alarming statistic in mind, you might see what I'm getting at by describing climbing as both autism-friendly and community-focused. By some stroke of luck, many of the social idiosyncrasies of climbing align to relieve autistic people of passing-type behaviours and allow them to socialise without burnout.

Struggle with eye contact? No problem, you'll spend most of your day staring at the rock or at your partner's forehead/bum. Not into small talk? You and your partner will spend most of the day on the other end of the rope, and one can hang out all day with people while not having to talk to them. To be honest, that's something I basically always want, no matter how nice you are. Sorry not sorry.

However, even the making of plans with a climbing partner can be daunting for people on the spectrum. Personally, if I'm having a rough week/month/whatever, I can't always bring myself to commit to a social occasion involving talking to others, because I just don't know in advance whether or not I'll be able to do so.

This is where the climbing wall becomes a blessing, because it offers a pre-made social occasion requiring no planning, to which people can just show up.* There's the option to socialise if one feels up to it, but there's also no obligation, and if executive function drops to critical levels, there's always the option to brood in a quiet corner or practise the underrated yet masterful art of the French exit.

Maybe I'm not making a compelling argument that many autistic people actually value social interactions, but the take-home message here is while I don't know a single autistic person who's genuinely an island, the connections with the mainland wax and wane with the tide, and climbing can make traversing these ephemeral strips of land more manageable.

*That said, the climbing wall can be a lot for some autistic people. See my suggestions section.

Managing uncertainty

If that self-indulgent metaphor hasn't turned your stomach and caused you to slam your laptop shut in a fit of rage, I've got a few more observations about the special role of climbing in autistic people's relationship with uncertainty. It's no great secret that many autistic people struggle with the variability of daily life, potentially because special sensory requirements and a reduced ability to recognise the internal states of others makes new environments and behaviours - however mundane - a potential source of anxiety.

Couple that with the fact that autistic people may struggle to recognise how close they are to their own limits, and it's no wonder that many autistic people come to favour repetitive routines and behaviours. For example, for the longest time I struggled to know whether what I was wearing was socially appropriate, so I wore basically the same outfit for about five years, and at a particularly chaotic point in my life I clawed back some stability by eating the same lunch for nearly a year.

Given that I'm apparently on the jagged edge of becoming a complete stereotype, it's a good thing that climbing itself doesn't have to change much if one doesn't want it to. In fact, countless climbing careers have been built on managing to not send projects for near-miraculous durations, a phenomenon I once wrote about in a piece with a now-embarrassing lack of gender balance (21 year-old Chris had a lot of self-discovery ahead of them).

Even amongst the degenerates who are indecent enough to actually climb things sometimes, the routines of a day's climbing can be very comforting. The near-automatic actions of putting on a harness, shoes and rack, tying on, going through the well-worn checks and phrases: all of this forms a comforting backdrop for a day which could involve a huge quantity of unknowns.

While you don't have to be neurodivergent to understand how the familiarity of a well-organised rack can keep your head out of the gutter on a knee-trembling onsight, I'd like to extend this observation into the lifestyle aspect of the climbing package, as I believe that these routines help autistic climbers tolerate more uncertainty in their daily lives, leading to a richer and more fulfilling existence.

Consider, for example, the experience of travelling out to a remote area of an unfamiliar country. The hack travel writer's line about stepping out of the airport and being bombarded by new stimuli - rich aromas, car horns blaring, blazing light - is straight out of many autistic people's nightmares, total sensory overload.

It's an unfortunate snag that while some autistic people may yearn for adventure, to get away from the frustration of their daily social obligations and become temporarily anonymous in a new place, the resulting break from routine introduces a huge barrier to doing so. However, autistic climbers may be able to manage these scenarios by scheduling a solid block of familiar bolt-clipping, wire-fiddling, whatever, in the middle of most days.

In doing so, they may be able to bring their daily dose of unfamiliarity down to tolerable levels, allowing them to experience the perks of adventurous travel. This resonates, at least, with my own experience: upon entering a new country, I often find myself inconsolable, mid-shutdown and desperate to give up and get the first plane back home, only for my spirits to become lifted almost the moment I tie on, pull on or even flick through the guidebook.

Beyond the travel-related benefits, I believe that most of the important moments of my life have happened against the consistent backdrop of my special interest. Many of the neurodivergent people in my family have chosen a calm and somewhat isolated life, and while I'm glad they've found something that works for them, I'm glad to have found a means of not, according to my own sensations, living on the sidelines.

Furthermore, as a young teenager struggling with my own unrecognised sensory and behavioural needs (and receiving the bullying to which around 68% of autistic children are subjected to by the age of eleven) the point at which I found climbing marked the first time I felt allowed to pursue my happiness on my own terms, and the awakening of the joyous and passionate elements of myself.

When I'm feeling macabre or just mildly hungry, I also wonder whether the outlet of climbing has helped steer me away from the more disturbing tendencies present in my genetic history, which may be related to neurodivergence. Yes I'm actually finishing this section by unironically stating that climbing saved my life, but this is my article and I call the shots here. In fact, not losing your heads in the forums, and instead showering me with compliments, will form a launching point in my…

Suggestions for allies

Believe people's lived experience: in my opinion, this underpins every other aspect of allyship. To genuinely empathise with and support autistic people, you have to trust them to accurately report a set of feelings which are inaccessible to you. If that sounds like a lot of work, remember that autistic people are performing these mental acrobatics every day in order to conform to societal norms. Furthermore, if an autistic person is struggling to articulate their experience, that doesn't make that experience less profound.

On a related note, the rate of gender nonconformity in the autistic people exceeds that of the general population, and the experience of these people should also be respected.

Understand what autism looks like for different people: as I've mentioned before, autism exists on a spectrum, and to understand how to be an ally to autistic people, it may be helpful to seek out testimonials across its full range, keeping in mind that many of these stories are male-focused.

In fact, due to society's heightened expectations and scrutiny of female social interactions, many women and people raised as female have developed sophisticated masking techniques in order to pass as neurotypical. These behaviours include pre-preparing conversation, forcing eye contact and mimicking others' social cues, and while this often leads to fewer female diagnoses, this doesn't invalidate their neurodivergent experience.

Recognise people's boundaries: if your autistic climbing partner says they'd appreciate, for example, some personal space, a breather in their climbing day, or to be home for a particular time, that may be because these requests are related to their core routines. Deviation from these routines may make them highly uncomfortable, although they may be too polite to say so. If in doubt, ask them whether or not this is the case, and where possible, allow them to direct these details to minimise their discomfort.

Avoid passing judgement for socially inappropriate but non-hurtful behaviour. You are not entitled to an opinion about another person's avoidance of eye contact, speech irregularities, or behavioural eccentricities. Not in the workplace, not at the crag and not at the pub.

Start an initiative at your local wall: the colourful and stimulating aesthetics of modern climbing centres can be challenging for some autistic people. The bright lights, loud music, coffee aromas and rainbow hold splatter can be, well, a lot. Couple this sensory overload with an unspoken social etiquette for taking turns on routes/problems, and you have a recipe for an autistic hazard awareness test - one from which some people on the spectrum might want to keep a healthy distance.

If you're a member of staff at a climbing wall, you may want to consider running sessions which cater to those with particular sensory needs. You could choose a quiet time, turn the music down, make the lighting a little less brash and focus on one particular hold colour. A few of these initiatives have already popped up, for example the SEND social at the Climbing Works. Join the future.

Remember that the entire community benefits from your allyship: as I've mentioned, the climbing community and society has profited greatly from its autistic members, and supporting these people is in your best interest. Please don't pat yourself on the back for doing the bare minimum, and try to share the discomfort that autistic people are keeping to themselves.

Suggestions for autistic people

Know your own needs: take the time to recognise your internal state, and figure out which situations you find triggering. Keeping a diary helped me with this. Once you've figured out those needs, set boundaries and communicate them to others - nobody can respect them if they don't know they exist. For example, you may want to show up to the climbing wall or crag at quiet times, clearly set your expectations for durations of sessions or ask for quietness rather than encouragement while you're trying hard.

Stop apologising for/caring about what others think: as someone who's spent way too much time trying to guess how others perceive me, it's been enormously liberating to abandon that line of reasoning entirely and ask "Who would I like to be if I were to completely disregard everyone's opinions?". In my case, living by my answers has made me a lot more fun to be around.

Consider the people around you: If your friends judge you for any of the above, find some better ones. There are plenty of people out there who'll appreciate you for all you are, even if it may not always feel like it amidst the isolation of autistic life.

Be visible: while the world is not currently particularly accommodating to autistic people, this does not have to be the case. There's strength in numbers, so educate yourself and become an advocate for your community. Take inspiration from your favourite social movement, start an initiative, find your people.

Know that you're valued: many of the autistic people I know, after rocky childhoods, are some of the most interesting and unique people I know. Even if they weren't, they'd still be just as deserving of love and respect as anyone else, despite a world which sometimes tells us otherwise. Figure out what closeness means to you, live on your own terms, and don't let anyone tell you how to feel. You are worthy, you are loved, you are not alone.

Some resources

Social media: for open and fun discussions of neurodivergence, my go-to is iampayingattention. I find that resharing their stories is a helpful low-effort way to communicate my experiences to neurotypical friends.

General information: during the writing of this article, I was pointed to the website Embrace Autism. The site contains loads of helpful information on what autism is, from a perspective on autism as a superpower rather than a disability.

Support groups: your local area will most probably have an autism/Aspergers support group. If in doubt, as a GP or mental health professional.

Diagnosing bodies: while the notion of autism as a "disorder" is falling out of favour, you might still like to pursue a formal diagnosis. The starting point is your GP, although you may be in for a wait of over a year.

Non-emergency mental health services: while I'm no expert in accessing ongoing mental health support for high-functioning autistic people, it still may be worth a conversation with your GP. For example, NHS South Yorkshire offered me a one-off block of 10-12 therapy sessions - albeit not autism-specific - as part of their IAPT scheme.

If you're in immediate distress: Samaritans offer a judgement-free listening service, 24 hours a day. There's also the National Suicide Prevention Helpline and Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM).

Comments

Really good article.

You could add https://www.autism.org.uk/ to your list of resources. They've got quite a lot of information and contacts plus a forum if you want to get advice from a bunch of people who have personal experience of autism.

Thanks Chris for writing this, it will help me greatly next time we climb together.

Thank you for writing this Chris. My partner recently received an autism diagnosis and you've articulated really well many of her experiences within climbing and in the rest of the world. Useful advice too. I'll try and thank you in person next time I see you at the Works.

Here are some other helpful resources:

Diagnosis - Psychiatry UK will provide an NHS funded diagnostic assessment via the right to choose process, the wait for this was around 3 months (I had an assessment early December):

https://psychiatry-uk.com/right-to-choose-asd/

Therapy/ Counselling - The ANDT provides a directory of autistic therapists/ counsellors/ psychologists spread around the UK (all private unfortunately, however I have found that I have made more progress working with an autistic therapist for an extended period of time than I was able to make with the NHS provided therapy which was unfortunately poor and difficult to access in Derby).

https://neurodivergenttherapists.com/

Autistic Self Advocacy Network has some helpful resources on their website:

https://autisticadvocacy.org/

This has some good resources for people looking to be allies or to understand the condition:

https://coda.io/@mykola-bilokonsky/public-neurodiversity-support-center

A useful glossary of terms can be found here:

https://autismacceptance.com/glossary/

I definitely find trips to the wall can feel overwhelming some times, more so since a sustained period of burnout, I'm slowly starting to climb again, but I still find it feels quite overwhelming a lot of the time.

Well, I enjoyed reading this refreshingly open story and its viewpoint enormously. Well done.