Anna Fleming explores the incredible life of Polish mountain climber Wanda Rutkiewicz.

'There is no escape from a passion like climbing, even though it may be the path to death.'

Polish climber extraordinaire Wanda Rutkiewicz was no stranger to violent death. Born in Lithuania in 1943, her family soon moved back to Poland and she grew up in war-torn Wrocław. When she was five years old, her brother refused to let her play a game with him and his friends among the bombed houses. She ran home in floods of tears to her mother, who raced out but was too late. The bomb the boys were playing with exploded, killing all of them.

Intelligent and athletic, Wanda was sporty in school, competing in high jump, shot-put, discus and javelin. She was selected for women's volleyball team to go to Tokyo Olympics in 1964, but she never went. A different passion had emerged that would shape the course of her life.

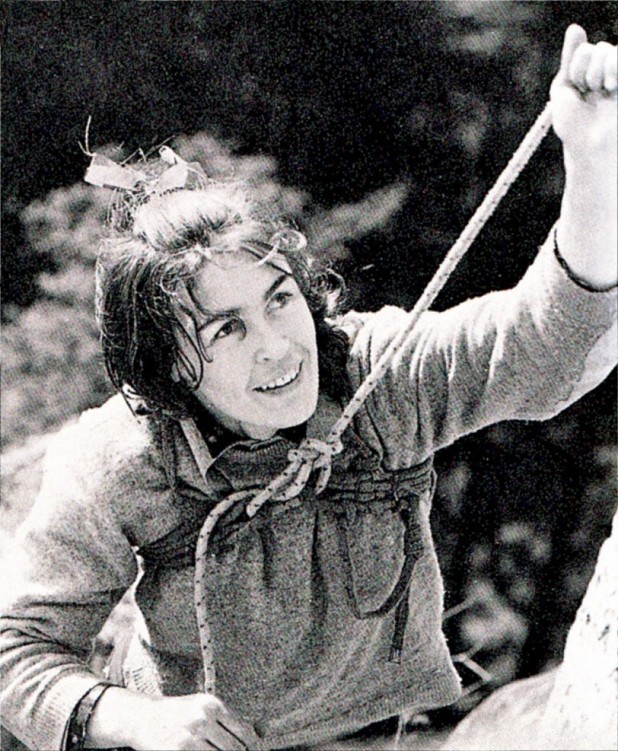

At the age of 18, some student friends took her to Husyckie Skały, a beautiful area of rocks, forests, and mountains in south-west Poland. There, she discovered climbing:

As Wanda's experience grew, her ambitions developed. She travelled west, crossing the Iron Curtain to climb in the Alps and Norway, where she and her climbing partner Halina Krüger-Syrokomska made the first women's ascent of the east buttress of Trollryggen in 1968. Coming from Poland at this time, Wanda was part of something special.

Despite being a poor communist country, Poland produced a number of climbers who did astonishing things in the high mountains. These climbers came into their own over the 1970s and 80s, producing hard-core achievement after achievement, but often at a high cost. They included Jerzy Kukuczka who became the second man to climb all fourteen 8000-metre peaks in 1987 - two years later, he fell to his death on Lhotse. There was also Voytek Kurtyka who pioneered Alpine climbing in the Himalayas, and Tadeusz Piotrowski who specialised in winter climbing. He died on K2 in 1986.

The climbers were revered in Poland, partly for showing the possibilities of travel and escape from the Communist bloc, as well as for demonstrating the power of Polish strength and determination to the world. Wanda was part of this movement but through her climbing, she was also tackling another formidable barrier.

In September 1973, Wanda climbed the North Face of the Eiger with an all-women Polish team. Over three days, the three women climbed through waterfalls and slept out in temperatures down to -10°C. All three suffered hypothermia and frostbite but this was just the beginning for Wanda.

The achievement on the Eiger, as a woman's team, was of critical importance to Wanda. Climbing was a man's world – and Wanda was a feminist. She was a champion of women's climbing, advocating for women's-only teams and climbing en cordée feminine. Her views were strong and unequivocal:

To develop this fair competition, in 1975 Wanda led an all-women Polish expedition up Gasherbrum III (7952m) in the Karakorum, Pakistan. The women did not know how they would be received in a Muslim country, so they combined their trip with a Polish men's expedition to Gasherbrum II. Happily it turned out their gender was not an issue as the locals 'didn't regard our ladies as women, but as white men of the female gender.'

The Gasherbrum III expedition was successful: Wanda and Alison Chadwick-Onyszkiewicz summited alongside Janusz Onyszkiewicz and Krzysztof Zdzitowiecki. But the trip was challenging as Wanda was not a natural leader and conflict rose around her zeal to separate the women's success from the men. Wanda was strong-minded, determined and obstinate. This made her a good fighter and climber but not the best at diplomacy or inspiring people to work together.

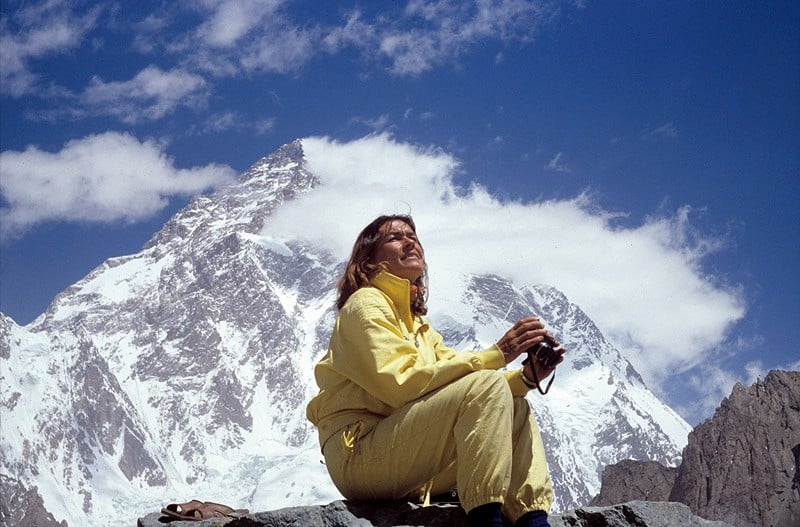

Wanda persevered. In 1978 she became the third woman and first Pole of either gender to summit Everest. In 1985 she climbed Nanga Parbat, the killer mountain. In 1986, after two prior failed attempts, she was the first woman to climb K2. Driven to achieve, Wanda's ambition was to ascend all fourteen eight-thousand metre mountains.

Funding these pioneering trips was not easy. Wanda noted the difference when she climbed K2 with a team of Swiss climbers. Whereas the Swiss had money and no time, the Poles had time and no money. Money made the trip easier for the Swiss, with relative comforts covered on the mountain, making their expedition more of 'an adventure holiday'. By contrast, from food to equipment, Wanda and her Polish companions worked to earn every part of their trips.

Sponsorship was not an option. Wanda was shy and she struggled to produce the charming audacity to court wealthy people. Instead, she began film-making to finance her expeditions. In 1989 she joined the British women's expedition to Gasherbrum II where she filmed the documentary Le Donne Delle Nevi / The Snow-Women, capturing the daily life of women's expeditions. She was one of the first people to film at 8000 metres.

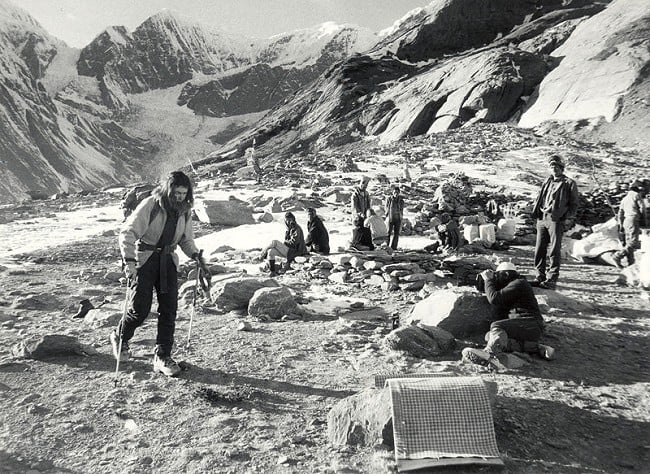

Wanda's life was lived to the full and packed with hard experience. She got meningitis in 1976 and had to re-learn how to eat, speak and walk. In 1982 she broke her leg but this did not stop her. Determined to climb, she hobbled all the way up the brutal 11-day walk-in to K2 basecamp on crutches. Following that unsuccessful summit attempt, she then walked all the way back out again on crutches. She was incredibly tough.

Yet beneath her strong exterior, Wanda described herself as an 'anxious person'. She struggled with the media circus which was intense after her success on Everest, leading to panic attacks.

She also experienced many traumatising losses. In 1972 her father was brutally murdered by a couple that had been living with him.

In 1982, Wanda lost her friend and climbing partner Halina Krüger-Syrokomska on K2. Hailna died very suddenly and unexpectedly in her tent in Camp II, from a heart attack or stroke. On the same mountain in 1986, after successfully summiting, Wanda's friends and teammates Liliane and Maurice Barrard died on the descent. In 1985, while Wanda was attempting to climb Broad Peak (8047 m), her friend Barbara Kozlowska drowned crossing a glacial river. Four years after Barbara's death, Wanda returned and recovered her body, removing it in a horrifying state of decay to give Barbara a proper burial beside Halina in the K2 graveyard.

With each of these experiences, Wanda worked hard to process her emotions and conquer any irrational fears. But she also knew that fear, in the mountains, was essential, recognising that 'fearlessness is a kind of deficiency.'

Wanda married twice and separated twice. She was not one to play the role of traditional wife and she had no children. She died in 1992 aged 49 on Kanchenjunga. This was her third attempt to climb that peak, which would have been her ninth eight-thousand metre mountain. Wanda was last seen sheltering inside a snow cave at around 8300m. It is not known whether she reached the top. Her body has never been recovered.

Confronting challenges both on and off the mountain, this remarkable climber left a phenomenal legacy. She proved what women are capable of in the distant heights.

- INTERVIEW: Catherine Destivelle - Rock Queen 8 Mar

- ARTICLE: Top 10 Borrowdale Routes at VS and Under 22 Jan

- ARTICLE: Herstory 7: The Rise of Women Mountain Professionals 27 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Herstory 6: Lhakpa Sherpa's Long Dream of Everest 31 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: The Climbing Cholitas: Skirts to the Top for Women's Empowerment 2 May, 2023

- HERSTORY: Alison Hargreaves: Climbing Her Mountain 7 Mar, 2023

- HERSTORY: Lady Climbers of the Long Nineteenth Century (1850-1914) 20 Dec, 2022

- HERSTORY: ORIGINS: The surprising origins of women's mountaineering - 1770-1830 9 Nov, 2022

- ARTICLE: The Cobbler: A Return to Mountain Cragging 7 Sep, 2021

- ARTICLE: A Climber in Lockdown 14 May, 2020

Comments

The word "history" comes from Greek, "historia" meaning "knowledge gained by inquiry". It's not related to "his/him" so there's no need to reinvent the word to introduce gender.

The word 'Herstory' is a commonly used term for history written from a feminist perspective or from a woman's point of view, so there's no need not to understand the context in which it's used.

Really interesting piece: thanks for this.

A good article; for a fuller account of Wanda's life "A caravan of dreams" by Gertrude Reinisch is a good read. I found it in an Oxfam book shop.

No one said it had masculine connotations lol.

It's obviously just a play on words between History & Her Story. You really can winge about anything 😅

Superb article. Thanks for sharing!