In memory of Tom Frost

In the 1960s, Yosemite became a climbing paradise. But what do you do when paradise is threatened with destruction?

In 1972, Chouinard Equipment, run by Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost, was busy making pitons when it ran into a problem. The problem wasn't their pitons, which were world-class. The problem was damage to cracks caused by pitons – everybody's pitons - being hammered into and out of the same placements. The most obvious damage was in Yosemite where some of the most beautiful cracks in the world were getting trashed.

At its simplest, pitons (pegs) are metal prongs which you hammer into a crack. You can use them for belays or protection or aid. Some early pitons had rings on the end. You could unrope and thread the rope through the ring, tie on and continue. Karabiners brought a huge advance. You could easily clip the krab into the eye of the piton and clip your rope into the krab. Quickdraws were many decades away.

The Munich School

Initially climbers could only use spikes or chockstones for belays or running belays or aid. In many rock types, spikes and chockstones are rare. The invention of pitons meant that, for the first time, you had portable protection - another huge advance.

The availability of this portable protection opened up some amazing routes on pretty big walls in Austria and the Dolomites in the 1920s and 1930s. However in Britain, with much smaller cliffs, pitons (castigated as the 'Munich School') were staunchly resisted.

Post World War II climbing technology consisted of pitons, ex-war department steel krabs (which weighed a ton), nylon ropes and nylon slings. Nylon was a huge advance over hemp rope. It stretched and didn't snap under stress. But nylon running across nylon would melt.

The most iconic rock climb in the world

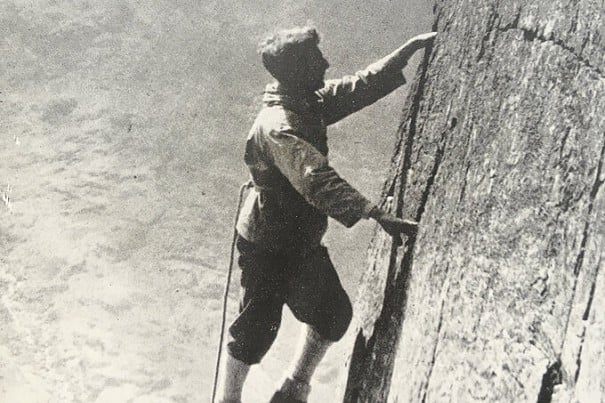

Armed with such state of the art technology, 1950s American climbers attacked the obvious challenges of Yosemite. In 1957 Royal Robbins and team climbed the North West Face of Half Dome, the first Grade V1 climb in America. In 1958 Warren Harding and team trumped this with the first ascent of The Nose on El Capitan – arguably the most iconic rock climb in the world.

Once The Nose was climbed, there were two directions in which Yosemite big walling could go. One was to do more routes on El Cap; the other was to do routes in better style. The first ascent of The Nose was made over several months. Robbins and his companions did the second ascent in one push. Yes, there was some ego involved (Robbins versus Harding) but there was also a sense of style - not just what you did but how you did it. Robbins became seriously interested in style.

Throughout the 1960s Yosemite steadily grew in importance. Camp Four became home to a Beatnik generation of climbers. Harder routes followed. In 1968 the first ascent of the North America Wall was done by Yosemite royalty in the form of Yvon Chouinard, Tom Frost, Royal Robbins and Chuck Pratt. This was the hardest big wall in the world. Rightly it was viewed as a huge triumph. However, it posed a fascinating question.

Conquistadors of the Useless

If you spent enough time on honing your skills and enough money on equipment, maybe you could climb anything? And, if you could climb anything, well really… what was the point? Lionel Terray had entitled his autobiography 'Conquistadors of the Useless'. Doubtless his existentialist Gallic irony resonated with the dirtbag Beatnik culture of Camp Four. But conquistadors of 'we can get up it any old way - by fair means or maybe foul'? That had a sour taste.

Doug Scott was the most accomplished British aid climber of the 1960s. In the early '70s he made an ascent of the Salathé. Around that time he wrote an excellent book called 'Big Wall Climbing'. He researched the history and found something intriguing.

Yosemite… a climbing paradise

When Ken Wilson started Mountain magazine in 1969 he envisioned a publication which would be the predominant authority on world climbing. He succeeded brilliantly. Mountain 4 - probably the most iconic issue of any climbing magazine ever - was virtually devoted to Yosemite. Ken had a brilliant photographic eye. He realised that Yosemite was a visual feast. With Mountain 4 he gave us a climbing paradise. Yosemite fuelled thousands of dreams. The trickle of foreign climbers would become a flood.

So, entirely understandably, when we thought of big walls, they were Yosemite big walls. But what Scott's 'Big Wall Climbing' revealed was that it had actually started in Europe, long before. While European walls may have lacked the aesthetics of Yosemite, they could still be very big and very mean. From the 1920s onwards, a host of Euro wads had done some very impressive routes in the Dolomites and the Austrian Alps. A classic example is the Comici Route on the Tre Cime – pretty radical for 1933!

'Where a drop of water falls, there shall I ascend…'

However, the Comici Route threw up the same ethical dilemma that would be raised in Yosemite 35 years later. About 80 pitons had been used. Was it excessive? Perhaps piqued by criticism, Comici soloed the second ascent in three and a half hours.

With wonderful European romanticism (hey, he was Italian!) Comici wrote 'Where a drop of water falls, there shall I ascend.' Thus was born the cult of the direttissima. Sounds good? Well, yeah, it did. But, as Oscar Wilde sagely noted, 'Each man kills the thing he loves.'

In the decades following Comici's death, there were quite a few direttissime forged on big walls. But lines of weakness rarely go straight from bottom to top. For instance, the 1938 route on the North Face of the Eiger wanders all over the place.

So while following the line of a mythical drop of water sounds great in theory, in practice it turned out differently. By the late 1960s there were direttissime that seemed little more than bolt ladders to be soullessly aided. With a piton, you need a suitable crack. But you can place a bolt anywhere. With bolts you can climb well-nigh any piece of rock – with not much skill involved.

The Murder of the Impossible

Direttissime were Grade VI – the highest grade given. Sure, they were big and serious. But how hard were they? One Grade VI might be E2. Another might be A2. Same grade; wildly different propositions.

In 1971, in a celebrated Mountain article, Reinhold Messner announced 'The Murder of the Impossible'. He laid into over-bolting and the cult of the direttissima. Climbers took him seriously. When he said we needed to take climbing ecology seriously, people listened.

But nobody really knew what to do. One celebrated experiment happened in Yosemite – and it wasn't a happy one. The then last great problem on El Cap was the Dawn Wall. Robbins' old nemesis Warren Harding returned, a decade after his celebrated trip up The Nose and made the first ascent. He used a lot of bolts. Had he created a masterpiece? A flawed masterpiece? An abomination? Who knew? The only way was for someone to go up and find out.

A flawed masterpiece?

Robbins aimed to do the second ascent of the Dawn Wall as he'd done the second ascent of The Nose – in better style than Harding. Specifically he started chopping bolts – more and more of them. And then, just to show how perverse fate can be, Robbins found himself up against some hard, committing climbing which Harding had clearly done without bolts. He stopped chopping. Even if too many bolts had been placed, maybe there could also be an ugliness in chopping them wilfully? (This was a lesson for the future.) To his eternal credit, Robbins did one of the hardest things that any of us can ever do: he publicly admitted he was wrong.

In the 1960s Lito Tejada-Flores had given us 'Games Climbers Play', a taxonomy of climbing 'games', from bouldering to Himalayan. To preserve validity, each had to be a game worth playing. So, for instance, using a ladder was fine in the Khumbu Icefall but ludicrous on a boulder problem. Underlying the notion of a game worth playing was the principle that adventure should be uncertainty of outcome where the outcome matters.

Enter three people

Bolt ladders were soulless. Excessive pitons were soulless. Bolt and piton damage was worse than soulless. It defaced the rock forever. Somebody had to do something. Sure, Robbins had tried – but the experiment hadn't really worked.

Enter three people: Yvon Chouinard, Tom Frost and Doug Robinson. Chouinard had started making pitons in the late 1950s, following John Salathe. Before Salathe, most pitons were made in Europe, of soft steel, typically for limestone. Soft steel deforms in limestone cracks; it's what you want. But granite cracks are a very different proposition. And Yosemite is granite. For granite, you want hard steel pitons. That's what Chouinard provided.

Bongs made a deeply reassuring sound as they went in. (The alternative to a Bong was a wooden wedge which would alarmingly expand and contract with repeated soakings and dryings.) Bongs were the biggest pitons around. Conversely the RURP (Realised Ultimate Reality Piton) was the smallest piton available - about the size and thickness of a credit card. To tap a RURP into a hairline crack and step up was wild, thrilling.

Chouinard Knifeblades, Lost Arrows and Angles Photos: Patagonia 1978 catalogue

Superbly functional, supremely beautiful

These pitons were superbly functional in granite. They were also supremely beautiful. Lost Arrows, Bongs, RURPs and Leepers (from Ed Leeper) came in matte black chrome molybdenum. They looked as though they'd escaped from a natural history museum. Because they were so good, they were favoured in Yosemite. Because they were so hard, they were more likely to damage the cracks. What to do?

In 1967 Robbins had visited the UK and been impressed with the sparing use of pitons. Joe Brown was a master of cunningly inserting chockstones in cracks. The next step was machine nuts, on nylon slings. The next step was purpose made nuts. One superb example was the MOAC, from John Brailsford. A well-placed MOAC gave almost as much confidence as a well placed piton. Robbins brought this knowledge back with him to the Valley. The 1967 pitonless route Nutcracker, led by Liz Robbins, was a deliberate statement of climbing style.

In 1971 Chouinard, his business partner Tom Frost and a young guide named Doug Robinson began making alternatives to MOACs. Robinson came up with an inspired name – stoppers. Although they weren't curved, otherwise they looked pretty similar to the wires you carry on your rack today. They were a classic design.

To complement stoppers, Chouinard brought out a different type of nut – the aptly named hexentrics. These went from pretty small to pretty big. But (and this was crucial) the torquing action of hexes, particularly big hexes, was just what you wanted for wide granite cracks. Taken together, stoppers and hexes provided a viable alternative to pitons. You could put them in and take them out repeatedly without damaging the rock. It was virtually 'leave no trace'.

'No longer can we assume the earth's resources are limitless…'

Chouinard and Frost made a crucial decision to advocate nut use rather than piton use wherever possible. They explained the rationale in their fabled 1972 catalogue.

'Granite is delicate and soft - much softer than the alloy steel pitons being hammered into it. On popular routes in Yosemite and elsewhere the cracks are degenerating into series of piton holes. Flakes and slabs are being pried loose and broken off as a result of repeated placement and removal of hard pitons.'

The Whole Natural Art of Protection

The solution? 'Start using chocks. Chocks and runners [i.e. nuts] are not damaging to the rock and provide a pleasurable and practical alternative to pitons on most free and many artificial climbs.'

Doug Robinson added an extended essay entitled, 'The Whole Natural Art of Protection'. It began thus: 'There is a word for it, and the word is clean. Climbing with only nuts and runners for protection is clean climbing. Clean because the climber's protection leaves little track of his ascension.'

The finest advertisement imaginable for the new creed of clean climbing

At around the same time, a young photographer named Galen Rowell snagged an assignment with National Geographic. Rowell photographed Robinson and Denis Henneck on the first hammerless ascent of the North West Face of Half Dome. It became the finest advertisement imaginable for the new creed of clean climbing. 15 million people were exposed to it.

In Robinson's words, "This slam dunked the clean climbing revolution - not what we did but the publicity generated by it. Within a few months you could not be caught slinking out of Camp Four with a hammer. It was that fast. Everybody got on board. Thank you, National Geographic."

For harder aid routes a hammer and pitons would still be needed. But The Nose and the North West Face of Half Dome were saved for posterity. So were many other smaller routes. Piton damage virtually ceased.

Interestingly, in his essay, Robinson noted, 'We must finally admit to still being a manufacturer of pitons. We are proud of our pitons and continue to refine their design and construction.' So they weren't saying, "Don't use pitons." They were saying, "Don't use pitons unnecessarily."

Thou shalt not wreck the place

Back at Mountain, Ken Wilson had discovered a talented young cartoonist named Sheridan Anderson, who depicted a victorious nut and a defeated piton. Another image featured a quasi-Biblical prophet holding a tablet of stone against a backdrop of snowy mountains. The edict was, 'Thou shalt not wreck the place' — a fitting commandment for ecology in all its forms.

The abrupt switch from pitons to nuts saved some of the most beautiful cracks on the planet from being defaced. It was a rare ecological triumph. Arguably it was the first major ecological movement in climbing. With his Clean Climbing essay, Doug Robinson laid down a better way.

But big changes would impact the climbing world. That 1972 Chouinard decision had consequences which nobody anticipated. Within 15 years, clean climbing would be in ruins. Yet ironically, 50 years later, it's more relevant than ever.

Those six words of Sheridan Anderson's said it all: 'Thou shalt not wreck the place'. His bittersweet humour was gently urging us towards a better world.

With very many thanks to the following for much-needed help with photographs: Robin Brooke,

John Dale, Jacob Harmer, Philip Garner, Ian Parsons and Patagonia archives. John Dale, of the Cleveland

Mountaineering Club has recently co-authored a book, 'North York Moors: Above and

Below'. It's a fascinating account of the history of the area, including climbing and caving.

He can be contacted via UKC. His nom de plume is Blackshiver.

This article was sponsored by Patagonia