Himalayan climbing books (speaking here as someone who never has, and never will, climb Himalayas) are a bit like bad video games. Plodding uphill, in a snowstorm, not really knowing where you are; and then pouf! You're dead. What is it about this one that has sold 11 million copies, making it the Number One mountaineering book of all time?

Well, it was written in 1951: just as the French were trying to rebuild national self-esteem after the defeat of World War 2. It involves two of the greatest mountaineering writers (and mountaineers) in France at the time: Chamonix guides Lionel Terray and Gaston Rébuffat. However, it was written by Maurice Herzog – who turns out to be the third….

But what makes the difference could be being written, in French, by French people.

The book's full-on in having an Introduction, a Foreword and a Preface and number three, the Preface, already shows where we're going. (Okay, no spoilers here, we're going to Annapurna.) It's written by the President of the French Mountain Federation. "A flame so kindled can never be extinguished. When we have lost everything it is then we find ourselves most rich…. The summit is at our feet. Above the sea of golden clouds other summits pierce the blue and the horizon extends to infinity. The summit we have reached is no longer the Summit. The fulfilment of oneself—is that the true end, the final answer?"

Such lyricism would be inconceivable from a President of the BMC. He then compares Maurice Herzog with Mallarmé – and no, this isn't the French spelling for Everest climber George Mallory… The French romantic poets, Mallarmé and Baudelaire and Rambaud, cherished the harsh, unpleasant and disgusting. With their general depravity, dangerous pleasures, bizarre outfits – they don't have anything in common with Himalayan mountaineers.

They don't. They really don't. Do they?

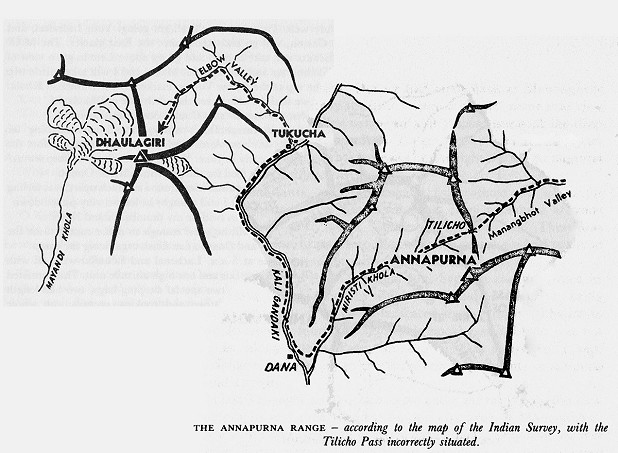

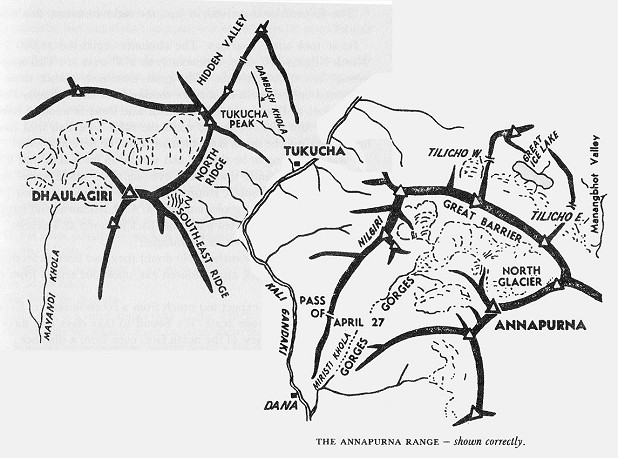

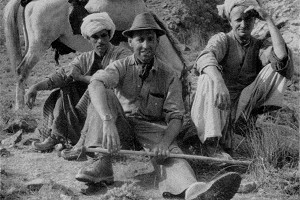

Hold these thoughts through the first half of the book, as the expedition assembles, treks out of India into Nepal, and carries out preliminary explorations. Not sure which hill they want to climb, they spend a month failing to find a way up Dhaulagiri before turning east. Then they spend a fortnight failing to find Annapurna at all.

Annapurna's northwest spur, in Herzog's description, sounds like a cracking Alpine mixed climb, maybe around AD+: the north ridge of the Zinalrothorn but ten or twenty times as long and up around the 6000m mark. Has nobody ever been back there? (A Polish expedition in 1996 climbed the upper part of it, the 'Cauliflower Ridge'). By the time they turn to the more straightforward (but horribly avalanche prone) north face, there are just 12 days left before the forecast arrival of the monsoon.

Which compels an agile and lightweight (by Himalayan standards) attempt at the first 8000m summit. (Pedant: members of Malory's Everest expeditions in the 1920s got well higher than Annapurna, er… Howard Somerville? Norton? Plus Frank Smythe in the 1930s. And who says Mallory himself never got to the top, eh? Me: Tais-toi, pédant!) The climbing is basically up an icefall, under kneedeep or thighdeep new snow in between the steep bits.

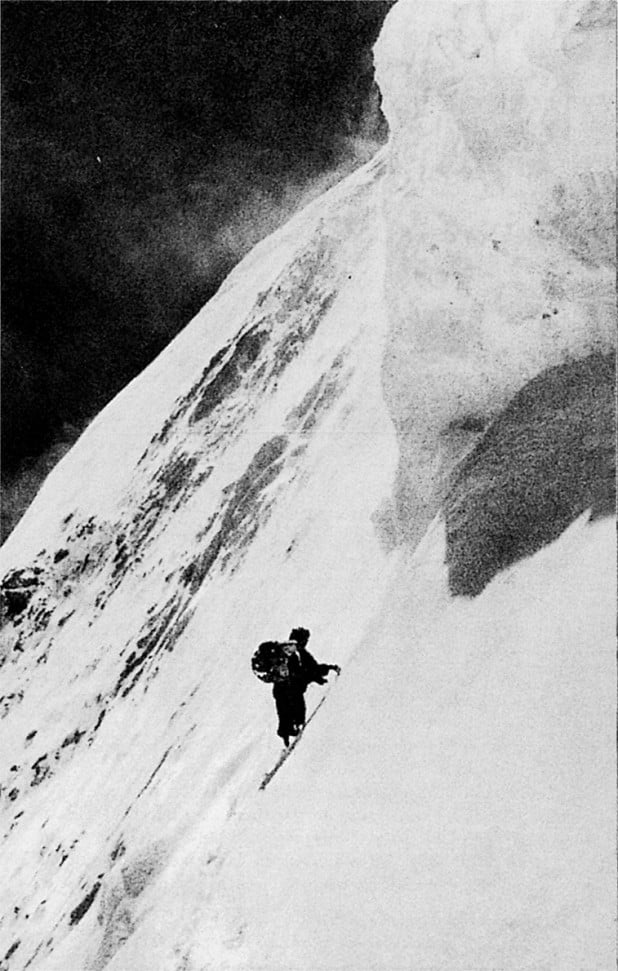

Ten days of climbing sees Herzog himself and top Chamonix guide Louis Lachenal cramponing up firm snowslopes from Camp Five to the summit.

But as everybody knows, the summit is only half way. A few moments into the descent, his oxygen-starved mind decides it needs something out of his rucksack. Did I mention, they're climbing without bottled oxygen? As he rummages, he drops his gloves. Both of them, and off they go down the north face into the avalanche couloir. He has spare socks he could use instead. But – as I know from my own experience, even the mildly chilled, somewhat hypoglycaemic mind of an ordinary hillwalker operating at full atmospheric pressure can't be bothered working out stuff like that…

Herzog arrives at Camp Five with hands frozen into solid blocks, and feet, in their Alpine-style Vibram boots, in a bad way as well. Lachenal doesn't arrive at all. In the mist he's missed the camp, and taken a fall, and he's lost his gloves as well.

In an outstanding feat of endurance, Terray and Rébuffat have climbed from Camp Two, moved tents from Camp Three to Camp Four, and continued up to Camp Five with supplies, all in the space of two days. Abandoning their own summit plans, they lead the injured climbers down through the snowstorm. All day, back and forward through the blizzard trying to find Camp Four. At nightfall they bed down in the bottom of a crevasse. In fine, simple prose, Herzog prepares himself to die.

In the morning a powder snow avalanche fills the crevasse. It takes an hour, with bare hands, to dig out all eight of the boots. And Terray and Rébuffat, who took off their goggles to lead the way in the fogs, are now snowblind, seeing nothing but mist.

And that's just the beginning of a mountain rescue that goes on, and on. Down the icewalls and the avalanches, the stony moraine. Out through the flooded rivers and mud of the monsoon. And on, through the paddy fields of Nepal, down into India. Just one detail out of the terrible journey. Right at the end, the train southwards along the Indian railway. Jacques Oudot, expedition doctor, waiting for the station stop to carry out another round of anaesthetic-free surgery. And as the train pulls away, a little pile of half-rotted toes and fingers, swept out onto the station platform…

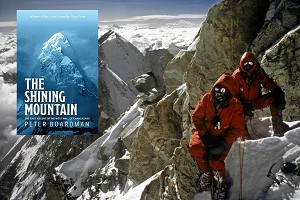

My American paperback of 1953 has a thrillingly inappropriate cover pic (featured at the top of this article: but at least the safety conscious protagonist is wearing his snow goggles). A lady on my train thought I must be reading science fiction. In compensation, it has a dry, British Introduction by Eric Shipton ("The achievement of the French expedition has won our wholehearted admiration and applause"). The 1997 Vintage edition has a cover that, for mountaineers, is every bit as exciting – the rock and ice wall behind the tents isn't even Annapurna, but the 'Great Barrier' of the Nilgiris, a mere 7000m high. Just look at that south spur of Nilgiri South – someone's climbed that now, they must have… (Hansjörg Auer, Alex Blumel, and Gerry Fiegl made a route here in 2015, Fiegl dying on the descent ). Eric's Intro is replaced by Joe Simpson, who was inspired by the book, as a schoolboy, to go up mountains himself and – yes, just like Maurice – to lie in the depths of a crevasse waiting to die…

Joe Simpson is more lyrical than Shipton: "Mountains have a stunning beauty, a coldly savage addictive quality that is difficult to resist and dangers to ignore." But he lets himself down, for me, with the traditional moral: "It is possible to win against all the odds if you just keep trying." Well yes: but it's even more possible, as Mallory discovered, not to.

The editor may correct me here, but this website hasn't so far explored the match between the 8000m summits and France's so-called Accursed Poets [it's all yours Ronald - Ed.]. Herzog's summit ecstasy (no other word will do) – don't worry, I'll quote it in a moment – might remind us, supposing we'd ever come across it, of Mallarmé's 'Les Fenêtres' (the Windows) where a dying man turns his shoulder to the world, longing for a life in the sky beyond.

Son oeil, à l'horizon de lumière gorgée,

Voit des galères d'or, belles comme des cygnes

Sur un fleuve de pourpre et de parfums dormir.

His eye, at the horizon gorged with light

Sees golden galleons, lovely as a swan,

Asleep on floods of perfume and of purple

Now here's Maurice Herzog, at 8091m, about to commence the most unpleasant six weeks in the mountains by anyone, ever:

Never had I felt happiness like this – so intense and yet so pure. What an inconceivable experience it is to attain one's ideal and, at the very same moment, to fulfil oneself. Never had I felt happiness like this – so intense and yet so pure. That brown rock, the highest of them all, that ridge of ice – were these the goals of a lifetime? Or were they, rather, the limits of man's pride?

This diaphanous landscape, this quintessence of purity – these were not the mountains I knew; they were the mountains of my dreams. The snow, sprinkled over every rock and gleaming in the sun, was of a radiant beauty that touched me to the heart. I had never seen such complete transparency; I was living in a world of crystal.

Well – was I really so far off with Mr Mallarmé?

Once again, in these writings about mountain writing, I've grossly overrun my word count. I don't have space to discuss 'True Summit" by David Roberts (2001) based on later journals of team members and showing that Herzog's account was, to some extent, self-serving.

But I do have to take a few more to credit the translators, Nea Morin and Janet Adam Smith. Their version from 1952 is reused in all later editions. Both were rock and ice climbers in their own rights. Morin, in particular, climbed in the Himalayas, was a pioneer of women-only ropes on hard routes in the Alps, and put up Nea (VS 4b **) on Clogwyn y Grochan. I hope to cover her autobiography, 'A Woman's Reach', here one day.

Just supposing the editor isn't too annoyed with my overrunning wordcounts.

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: Native Stones by David Craig 3 Nov, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: Mont Blanc, Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni 20 Oct, 2022

Comments

Pity you couldn't find a few more lines to add more about David Robert's book & the reaction to it in France. Maybe another article ?

This book is such a gripping read.

Can totally understand you going over your word count!

Will always have a plethora of mixed emotions about this book.

Isn't there a rumour that either Nea Morin and Janet Adam Smith wrote the brilliant last line?

Mick

P.S. Can we have Janet Adam Smith and Nea Morin in this series?

What was the reaction (or reactions?) in France?

I had even more mixed emotions about this one!

Mick

I read it a couple of years ago back to back with Mick Connefrey's Everest 1953 and the difference between those two ascents, only a couple of years apart, really struck me. The French returned with frostbitten hands and feet all over the place and seemed to wing important parts of the expedition. By comparison the 1953 Everest expedition was almost boring in its efficiency!

Both great reads though.