From wherever-Camelot-was, eight weeks through Wales to the Peak District, in winter conditions: that's a fair hike, says Ronald Turnbull, even in Gore-Tex lined boots with modern footpath signs. These Dark Age verses on an arduous quest must be the first account in English (or thereabouts) of a long-distance bivvying trip.

Mony klyf he ouerclambe in contrayez straunge,

Fer floten from his frendez fremedly he rydez.

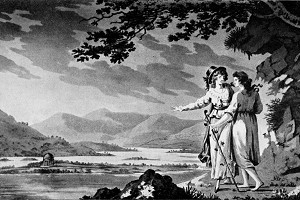

This could even be the very first hillwalking strapline in Middle English. 'Many cliffs he clambered up in countries strange; wandered far from his friends, as a foreigner he rides.' Some time in the Dark Ages, maybe 1500 years ago, the knight Sir Gawain, along with his horse Gringolet, sets out on a serious long-distance hike through Wales and the Peak District. An eight-week journey, from autumn through into early winter, sleeping out in the open in cold iron armour.

Near slain with the sleet he slept in his irons; More nights than enough in naked rocks

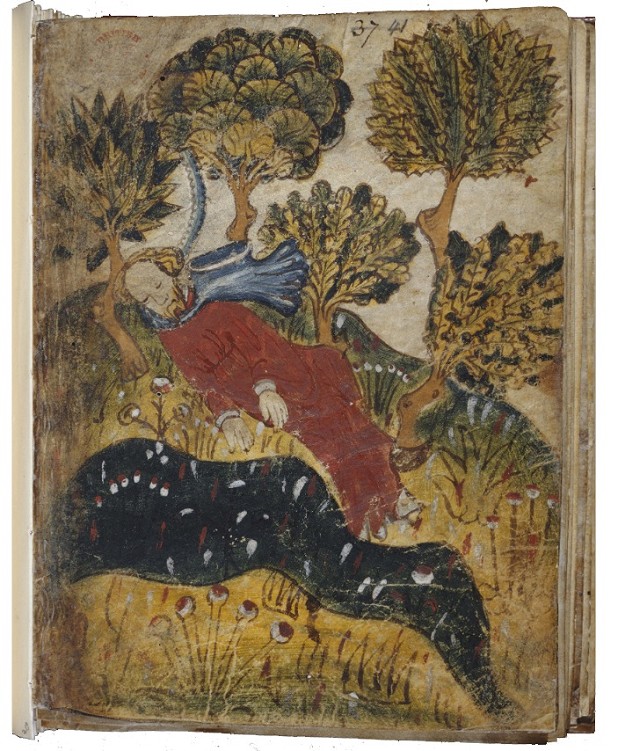

In 1839 a librarian came across the single copy of the 2530-line Gawain poem, inscribed in tight little handwriting on sheets of calf-skin along with four faded illustrations. The name of the poet is unknown. He or she lived and wrote at the same time as Geoffrey Chaucer. But instead of Chaucer's jolly group walk along the road to Canterbury, this is a dangerous bivvy trip through the wilderness; and instead of Chaucer's almost-modern English and decorous rhyming couplets, here's an older and more rugged Middle English from Middle England, somewhere around Staffordshire. And their verse-form went back to Beowulf and the old Anglo-Saxon language: the line with four stressed syllables and a gap in the middle, with three of the stresses starting with the same alliterative consonant – klyf, clambe and contray in the line at the start of his journey.

Gawain was not a hiker of today, setting off up the Offa's Dyke Path for whatever reason we set off up Offa's Dyke for. The word 'adventure' was brought into English by King Arthur himself (well sort of). The story behind Gawain's one is a bit complicated.

It's Christmas, at Camelot. Arthur, as is his custom, won't let the meal begin until 'sum auenturus þyn' has been related, or happened in real life. That weird letter Þ is 'thorn', pronounced like the voiced th in breathe, or the Welsh dd in Carneddau. The other weird letter, yogh ȝ as in Sir Gawayn and þe Grene Knyȝt, is the CH sound of Scots and Gaelic 'loch'. Yogh became the silent z in many Scots placenames, such as Drumelzier Hill above the Tweed, or Ben Chonzie pronounced 'Ben-y-Hone'.

Before everybody's got too hungry, the adventurous thing occurs. Into the hall rides a strange knight, green all over including his hair and his horse, and carrying an enormous axe.

Okay, so some authorities think the weird green colour may be some Saxon's misunderstanding of the Celtic 'glas' which can mean anything between green and grey – as in Glaslyn and Glas Maol. But who wants to hear about the Slightly Colourless' Knight?

The moors and the mountains were muzzy with mist; and every hill wore a hat of mizzle on its head

Anyway, the Green Knight challenges everybody to a 'Christmas game', a jolly head-chopping contest. Some brave champion is to use the enormous axe to cut off the Green Knight's head. And in return, a year and a day from now, the Green Knight gets to have a go with the axe himself. This is a dodgy proposition and nobody goes for it, which is a bit embarrassing for King Arthur. At last Sir Gawain, the best and bravest of the knights, steps forward and offers to have a go.

Gawain successfully chops off the Green Knight's head. The Green Knight picks it up again, leaps on his green horse, and with a brief but terrifying parting speech, gallops off into the night. Ten months later, on All Saint's Day, Gawain sets out on his quest to find the Green Chapel and his New Year rendezvous.

The stanza starting at line 691 describes his journey through the hills and forests, sleeping out alone in his cold armour, consoled only by the image of Jesus' mother Mary on the inside of his shield. Nearly every river crossing was defended by an enemy knight he had to fight. We have to imagine him at night hanging his food in the branches because of the bears; Wales in those days was also infested with bison, dragons, wolves, wild boars, ogres and even wodwos – those being a sort of cross between a human being, a holly tree and a hedgehog. But just as for walkers on Offa's Dyke today, the worst of it was the weather:

Ner sleyn wyth þe slete he slept in his yrnes

Mo nyȝtez þen innoghe in naked rokkez

Þer as claterande fro þe crest þe colde borne rennes

And hinged heȝe ouer his hede in hard iisse-ikkles.

Near slain with the sleet he slept in his irons [armour]

More nights than enough in naked rocks

Where as clattering from the crest the cold burn [stream] runs

And hanged high over his head in hard icicles.

The previous stanza indicates his route-plan: starting wherever Camelot actually was (take your pick) through to North Wales, leaving Anglesey on his left. Then through the wilderness of the Wirral, where the few inhabitants are hated both by God and by their fellow men.

The pandemic-year film starring Dev Patel puts in various updates to the storyline, giving Gawain a girlfriend and adding in an animatronic fox. But it leaves in the long-distance trek, shooting it entirely in Ireland and featuring the Wicklow mountains instead of Snowdonia.

Gawain spends Christmas in a convenient castle. And that turns into an adventure of a different kind, as its mistress tries to make love to him, bringing his courtesy and his chivalry into direct conflict. But the only outdoor activities, a bit of hunting, happen offstage.

So now, here is Gawain setting off for the Green Chapel, in what could be the finest bit of outdoor writing left to us in Middle English. For full effect try reading it aloud, bearing in mind the values of thorn and yogh, and using a Derbyshire accent if you've got one:

þey boȝen bi bonkkez þer boȝez ar bare,

Þay clomben bi clyffez þer clengez þe colde.

Þe heuen watz uphalt, bot vgly þer-vnder;

Mist muged on þe mor, malt on þe mountez,

Vch hille hade a hatte, a myst-hakel huge.

Brokes byled and breke bi bonkkez aboute,

Schyre shcaterande on schorez, þer þay doun schowued.

They scrambled up bankings where branches were bare,

clambered up cliff faces where the cold clings.

The clouds which had climbed now cooled and dropped

so the moors and the mountains were muzzy with mist

and every hill wore a hat of mizzle on its head.

The streams on the slopes seemed to fume and foam,

whitening the wayside with spume and spray.

Trans Simon Armitage

The Green Chapel turns out no chapel at all, but an atmospheric chasm among the rocks. Given the landscape described, the Peak District dialect of the poem, and the proximity of the Wirral on the way in, it's been identified as Lud's Church, a landslip chasm above Gradbach and underneath the Roches.

From wherever-Camelot-was to the Peak District, in winter conditions: that's a fair hike, even in Gore-tex lined boots with modern footpath signs. The only recorded walk since Gawain himself was by Simon Armitage, the poem's translator, Pennine Way walker and current poet laureate.

Seems like a sad lack of traffic for England's oldest long-distance walk.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

The edition co-edited by Tolkein (the Lord of the Rings man) has useful notes and a Middle English glossary that's longer than the poem itself. Tolkein also, separately, published a translation.

The Armitage translation also has the original text in parallel.

- The Green Knight, written and directed by David Lowery, was released in 2021. Trailer here

- Simon Armitage documentary (BBC4)

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: Native Stones by David Craig 3 Nov, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: Mont Blanc, Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni 20 Oct, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush 3 Oct, 2022

Comments

Both instructive and entertaining. Thanks.

Simon Armitage is a northern lad and his translation reads well to someone similarly from the north of England.

Thanks, a really enjoyable and evocative piece. That patch of land around Back Forest and Gradbach Hill is pretty much my favourite bit of the Peak District, and perhaps a little bit of that is because of the associations with this great poem (made so much more accessible by the Simon Armitage translation). Walking through those woods and moors on a dark and misty November day brings some of those lines to life.

Probably a Staffordshire accent rather than Derbyshire.

A few years ago the author Alan Garner wrote about this poem in The Times and described its setting in the modern landscape. He tells how he read it to his father, who spoke the old Staffordshire dialect and had far less trouble understanding the language of the poem than Garner's tutors at Oxford.

Great fun...thanks.