Mark Horrell reviews the film Nawang Gombu: Heart of a Tiger, a profile of a much-loved but little-known Sherpa.

When I watched the 46-minute documentary Nawang Gombu: Heart of a Tiger on YouTube, it had only been watched 151 times before me. This is ridiculous, given that another one of a man opening a beer bottle with a chainsaw had been watched 3,234,053 times (one more than that after you just Googled it).

I've mentioned Nawang Gombu previously. He was the nephew of Tenzing Norgay, and one of my chosen ten great Sherpa mountaineers. Nawang Gombu: Heart of a Tiger has flaws as far as documentaries go, but it deserves to be watched more widely because of its subject matter.

There is a treasure trove of historical archive footage, and an astonishing number of people have been interviewed to celebrate the life of this extraordinary man: the great and the good of American and Indian Himalayan mountaineering of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, almost his entire extended family, as well as friends from his childhood. At times it causes the film to feel disjointed and repetitive as we are rushed through soundbite after soundbite of people making the same point in different words. But you get the overall message: Nawang Gombu was loved and respected by everyone who knew him. And the positive side of this approach is a wealth of endearing anecdotes that help to paint a picture of his character.

The film has a bizarrely shouty narrator who seems to be auditioning for a female version of Brian Blessed (and she is remarkably successful in this respect). It also begins in irritating fashion. The first 60 seconds consist of soundbites trying to answer the perennial question of why people climb.

'Why would we do anything? Why do you ski?' we hear one voice say, clearly irritated by the question.

I might add: why watch celebrity cake-baking contests, or TV talent shows involving rank amateurs? In the case of mountaineering this question has been asked enough times, and enough decent answers have been provided. We don't need to keep asking it.

In Gombu's case this question is answered in more detail later, but without reference to this opening sequence, so we forget that it was asked. His reason is an important one. He was a Sherpa, and although he loved his job, he climbed primarily as a means of supporting his family through school and giving them a route to a better life. This is the same reason climbing Sherpas still do the same job today. As Tenzing Norgay's nephew, Gombu provides a direct link back to the mountaineering pioneers, and his educated offspring interviewed in the film provide evidence that it can be a successful route.

The question passes and Gombu's friends and family tell us about his early life. He was raised near Thame, in the Khumbu region of Nepal, but as a boy he was sent to the Rongbuk Monastery in Tibet to train as a monk. He hated it there. Boys were beaten with sticks if they forgot their prayers, and after a year he escaped and fled back over the Nangpa La into Nepal. There follows one of those annoying sequences in which about 20 different people (OK, more like five) explain what an amazing achievement it was for an 11-year-old boy to flee over this glaciated pass. Perhaps for western boys, but the Nangpa La is a principal trading route for Nepalis and Tibetans. I've been up it myself. It's true, there are crevasses; but, on the Tibetan side at least, it isn't especially difficult.

Gombu moved to Darjeeling, where his uncle Tenzing took him under his wing. We learn that Gombu was incredibly strong, and although he was only a little over five feet tall, his chest was as broad as a barrel.

We learn about the incident when a 17-year-old Gombu berated expedition leader John Hunt for carrying only one oxygen cylinder during the 1953 British Everest expedition. We are told that this character trait remained with him throughout his life; Gombu liked to speak his mind, and he was not especially diplomatic – 'he called a spade a spade' is how one of his daughters described him – but people regarded this as a good characteristic.

Gombu became an instructor at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (HMI) in Darjeeling, an organisation set up by the Indian prime minister Nehru after Tenzing's ascent of Everest in 1953, with Tenzing as its director. The HMI brought Gombu into contact with many American and Indian expedition organisers. He climbed with the Americans Willi Unsoeld and Will Siri on Makalu in 1954, and in 1960 he reached 8,600m on Everest with an Indian expedition.

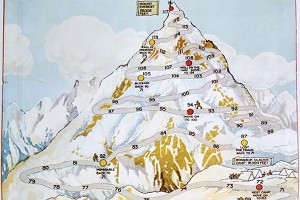

In 1963, Gombu joined the American attempt on Everest, an expedition that was to turn him and many American climbers into mountaineering superstars. Historically this expedition has become best remembered for Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein's first ascent of the west ridge, in which they traversed the summit and descended its south-east ridge.

At the time, however, it was Gombu's ascent of the south-east ridge with Jim Whittaker that held the spotlight. At 6'5", Whittaker was a foot taller than Gombu, and they made an odd pairing, but together they became the first American and second Sherpa to reach the summit. Whittaker is interviewed at length in the film, and describes their gentlemanly 'you go first', 'no, you go first' sequence as they approached the summit. Eventually they stepped onto it together, avoiding the childish controversy that followed Tenzing and Hillary's ascent.

After the expedition, Gombu and four of his teammates were taken to America. They met President Kennedy, and Whittaker relates a story of how they asked the president to feel Gombu's thigh. The Sherpas were given a giant Cadillac to drive across America. When the police stopped them for speeding, they were let off after complaining 'but officer, don't you know who we are?'

Gombu returned to Darjeeling in high demand. In 1965 he was invited to join another Indian expedition to Everest. He asked them this question:

'But I already climbed Everest in 1963. Why should I go there again and again?'

He was offered scholarships for two of his children and a plot of land. He was also promised a place in the first summit party. These offers were enough for him to accept. In May that year he reached the summit again, a historic achievement that one of my favourite interviewees in the film, Colonel Narender 'Bull' Kumar (whose nickname is self-evident) describes with a huge grin: 'I used to very proudly introduce him as the only man in the world who has climbed Everest twice.'

Much of the second half of the film focuses on Gombu's later career as a mountain guide in the United States (where he also became the first Sherpa to climb Denali, the highest mountain in North America).

Phil Ershler, one of the founders of American super-operator International Mountain Guides (IMG), relates a story of when he was a novice mountain guide on Mount Rainier. He was nervously glancing around a crowded mountain hut, 'looking like a lost puppy dog', trying to find a spare bunk when Gombu – now a mountaineering legend – slung his own mat and sleeping bag onto a pile of ropes and said 'Phil, you sleep here.' Ershler has a look of awe in his eyes as he delivers the last line of the story: 'And that's how I met Nawang Gombu.'

Much of the final part is given to Gombu's sons and daughters to reminisce about their father. They talk about how tourists used to turn up at their house in Darjeeling as though it were a shrine. When they were still children he used to ask them to write letters for him in English promoting a particular cause or reference for someone he had agreed to help. He became very active in the Sherpa Buddhist Association, an organisation originally set up as the Sherpa Climbers' Association to help the families of Sherpas injured or killed in climbing accidents.

There is a somewhat teary ending to the film. Gombu died as recently as 2011 and he is still fondly remembered. One of his daughters, Rita Gombu Marwah, became a mountaineer herself, and got to within 183m of the summit of Everest in 1984 before turning around when she saw a storm approaching. There is one sequence in which she is translating on behalf of her mother, and both are crying as she completes the sentence.

'He was really hard-working and very caring and he always wanted to help people … he was always concerned about everybody, not only his family but the rest of the people in the community.'

His character is perhaps best summed up by Jim Wickwire, the first American to climb K2, who climbed with Gombu on an expedition to the north face of Everest in 1982. On that occasion, Gombu promised his family he would not try and reach the summit, even though he was still in his forties and easily strong enough. Wickwire said:

'He was just a great guy to be with in the mountains, never down. He was always optimistic, always up, and that's the kind of person you want to be around on an expedition.'

It's easy to overlook the film's many little faults and annoyances when you consider it as a whole. All the archive footage and interviews make it an excellent historical record, but most of all, it's a great tribute to a man who deserves to be remembered.

Comments