You've heard of Hannibal's crossing of the Alps, but what other lofty feats took place in mountainous areas long ago? Author of an upcoming book on ancient mountaineering history, Matthew Shipton, shares some tales of high altitude adventures from the ancient world

'At about the last watch, with enough of the night remaining for them to be able to cross the plain under cover of darkness, they got up when the signal was given and marched towards the mountain…' Anabasis, Book 4, chapter 1

In the violet-dark of a mountain dawn the Greek mercenaries struck camp. They had been travelling for more than six months, having crossed the Taurus Mountains in late spring, and now found themselves on the threshold of the Armenian Highlands. Ahead, a mass of steep sided hills occupied by the Carduchi. They were a warlike tribe – a Persian army of 120,000 was said to have perished here, so rough the terrain, so hostile the locals. And beyond them the prospect of an ascent of the Pontic Alps, the final barrier between the Greeks and the Black Sea, where hope of escape might be realised.

The date was autumn 401 BCE and the account is that of the young Athenian, Xenophon. His Anabasis, or The March Upcountry, is one of the most exciting tales of Greek heroism that survives from ancient times. It tells the story of 10,000 Greeks enlisted by the Persian King's brother, Cyrus, in his attempts to win the throne by force. But it is also a remarkable document of ancient adventures at high altitude.

Most of the Greeks came from the Peloponnese, the poverty of rugged landlocked Arcadia or the dull neutrality of neighbouring Achaea providing cause for many a young man's wanderlust. Mountain terrain would be familiar to them, and not just through myth. While 'snow-capped Olympus' or Helicon 'whose muses go forth, veiled in thick mist, and walk by night', featured in their founding tales, the mountains also served practical purposes in ancient Greek society. Not untypically, Mount Kyllini, a Peloponnesian peak second in height only to Taygetos at 2,380m, and sitting close to the major Arcadian settlement of Orchomenos, was topped in antiquity by a temple. In this case it was to Hermes, 'a bringer of dreams, a watcher by night, a thief at the gates', patron of travellers and wayfarers and tormentor of Prometheus, bonded by adamantine to the Caucasus mountain top. And a famous scene from the Greek play of 458 BCE, Agamemnon, suggests the existence of a relay of mountain top beacons. Aeschylus writes of sentinels connecting Ida on the plains of Troy, the 2000m pyramid of Mount Athos, rising precipitously from the Aegean Sea to Macistus' (literally 'tallest') on the mainland as, 'the never-dimmed flame burned brighter still, shining like the radiant moon, until it reached the rocks of Cithaeron… on it sped, down to the lookout near our city, perched on the peak of Arachnaeus (Spider Mountain)' But the mountains the adventurers travelled through in Asia Minor were larger, much larger than those of their homelands, the conditions much more severe.

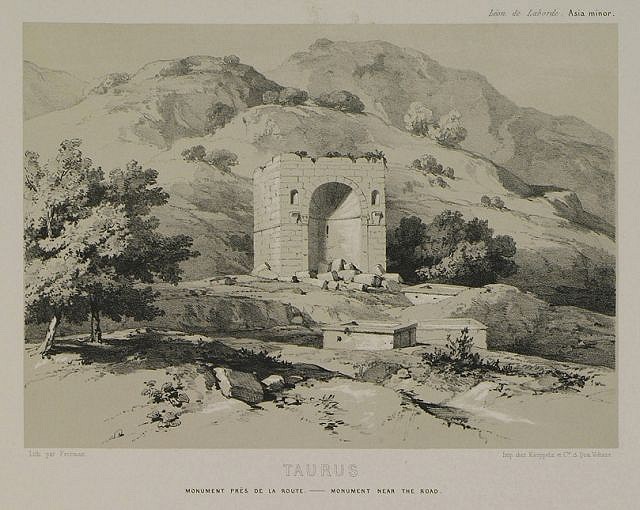

Earlier in the mercenaries' expedition, before Cyrus was killed at the battle of Cunaxa near Babylon, they fought their way through to the foot of the first major mountain pass, The Cilician Gates. The Gates cut a slender channel through the towering wall of the Taurus Mountains, the shark fin peak of Medetsiz Tepe (3524 m) to the west and the thuggish bulk of Ak Dag to the East (3213m), forming a near impassable rock barrier for those attempting to reach the ancient city of Tarsus on the plains of Cilicia. Echoes of earlier battles would have resonated with the Greek force. The doomed Greek heroism of the defence of Thermopylae 'the Hot Gates' against an invading Persian army, said by Herodotus to number in the millions, not 80 years earlier remained a strong cultural memory. In the shadow of Mount Kallidromo, the Greeks, including a detachment from Orchomenos, fought the Persians for seven days before being outflanked and their famous Spartan-led rearguard destroyed. In a reversal of events at Thermopylae, the army deployed at the Cilician Gates, loyal to the Persian king, fled after betrayal by one of their own. But passage through the Taurus was to be costly. Xenophon reports that two companies, 100 soldiers, of the rear guard vanished and speculates darkly as to what Fate befell them. In this weathered and friable karst terrain, prone to seismic activity, it's easy to imagine rockfall or slips into the precipice. Ambushes awaited those who became lost too but it's tempting to imagine whispers of worse. The Greeks had their own stories of terrors who inhabit the high places, such as the figure of Cycnus who dwelt in the pass of Thessaly and built a temple to Phobos, the personification of fear, from bones of the lost adventurers he'd slaughtered.

But the bulk of the Greeks survived. They continued for some months, fighting and winning until a rash charge by Cyrus at the Persian king saw the young challenger fatally wounded. Now pursued by the king's army and abandoned by local allies, they struck north in an attempt to reach the sea. The Greeks fought running battles with the Carduchi for seven days as they passed through the Mount Judi range, said to have been the final resting place of Noah's Ark, before arriving at the river Centrites that flows south west from Lake Van into the Tigris. Xenophon recounts hard days. A Boreal wind sent heavy early season snow, more than six feet deep and 30 soldiers died of exposure along with uncounted numbers of slaves and animals, the dead horses left frozen in the snow like fragments of Parian-marbled statuary. Sacrificial offerings were made to appease the gods and the wind eased. But the cold and snow persisted; the following day's march saw many soldiers fall, exhausted and malnourished. Having set out in spring and endured the shimmer-heat of a Mesopotamian summer, they were ill equipped for winter. Early in their flight, when Persian trickery had led to the capture and execution of their generals, allowing Xenophon a more prominent role, they had agreed to burn their tents and much of their equipment to make swifter their escape. In miserable snow holes, as enemies encircled, they couldn't risk camp-fire light giving away their positions; when moving those caught snowblind, or with toes lost to frostbite, were left to die as the main force struggled on. But through harsh necessity, they did discover some means of battling the elements:

"It was a relief to the eyes against snow-blindness if one held something black in front of the eyes while marching; and it was a help to the feet if one kept on the move and never stopped still, and took off one's shoes at night."

Temperatures as low as minus 40 are not uncommon in the region during winter. Having walked so far their footwear would have been worn to nothing and Xenophon says many responded by fashioning foot covering from freshly flayed ox-hides. The conditions, and lack of equipment, must have been brutalising.

A sudden stroke of fortune gave distance between them and the pursuing Armenian forces. They came across a scattering of more welcoming villages in the foothills of the Pontic Alps where they could rest, eat and shelter from the elements. Having recovered their strength they pushed further into the mountains. What opposition they encountered they overcame, even when faced with defended peaks. Xenophon writes of the storming a hill-top stronghold, the Greeks having dodged hails of boulders thrown down pine wooded slopes. As they breached the walls they discovered a grim sight. Unwilling to be taken captive, the inhabitants threw themselves off a cliff edge, killing themselves and their children. This passage is gruesome to modern readers but must be read against the reality of Spartan life (they made up large numbers in the mercenaries' ranks too). The highest peak on the Peloponnesian peninsula, Mount Taygetos, standing at 2,400m, played an important role in Spartan society. The Ceadas ravine is gouged out of Taygetos, around a third way up the eastern flank, and was where ill or deformed Sparta infants were left to die of exposure. The killing of one's own children on the mountainside appears a grisly commonality between the two cultures. The location of this macabre event is uncertain and Xenophon is strangely taciturn is his narrative of the mercenaries' negotiation through the Pontic Alps. It has even been speculated that the Greeks became lost by his faulty navigation amongst the labyrinth of passes and bounding ridges. It is possible too that Xenophon took the Greeks on a circuitous route, moving up through complex parallel valleys and under the shadow of 4000m high Kackar Dag.

What's more certain is many days later they arrived at the ancient city of Gymnias, likely to be modern day Bayburt. Here they found the inhabitants in conflict with tribes to the north through which the Greeks would march and thus an alliance of interests. The governor of the region offered a guide to the Greeks and promised that after 5 days of marching they would find themselves atop the mountain from which they would look upon the Black Sea, and the final route home. True to his word, on the fifth day, they arrived at Mount Thekes - possibly the Zigana Pass (2000m) or Deveboynu Tepe (2850m) - and the shout went up from the Greeks: "Thalassa Thalassa!" "The sea, the sea!" They had survived, though at great cost, having lost hundreds of men to death in the mountains. In Xenophon's account we have some of the earliest descriptions of high altitude warfare, the use of winter techniques to combat the elements and the services of mountain guides.

Perhaps, if we search the ancient sources with same spirit of adventure of a Xenophon we will find much more evidence for mountaineering in millennia past. The stories of Hannibal in the Alps, Pompey in the Caucasus, Alexander the Great in the Karakoram or Nero ascending Etna are well attested, but there's much more to be rediscovered: tales of ancient mountain rescue, trade, communication, warfare, love, sightseeing, exploration, all set amongst some of Europe and Asia's highest peaks The tantalising prospect emerges that, travelling through the rough-hewn terrain of their world, we will discover a more adventurous relationship between the ancients and the mountains than has been previously credited.

About the Author: Matthew Shipton grew up in Sheffield where he was first taught to climb on school trips to Stanage. Now based in London, he is currently writing a book on the ancient history of mountaineering. His first book, The Politics of Youth in Greek Tragedy: Gangs of Athens, is published by Bloomsbury on 8 February.

Comments