On the 4th anniversary of the first ascent of The Dawn Wall by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, we are pleased to release this multimedia interview with Caldwell that took place during the 2018 Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival in Alberta, Canada.

Tommy Caldwell didn't enter this world smoothly. Born seven weeks premature in August 1978, a tenuous birth and survival against the odds set the tone for a life that would come to be defined by enduring hardships and challenging expectations. 'Not giving up seemed to come naturally to me,' Caldwell writes of his earliest days in his acclaimed autobiography The Push, published in 2017. This resilience has since bolstered him through some turbulent times: a reclusive childhood; a traumatic hostage situation in Kyrgyzstan in 2000; the loss of an index finger in a DIY accident, a difficult divorce and a particularly stubborn 7-year-long climbing objective.

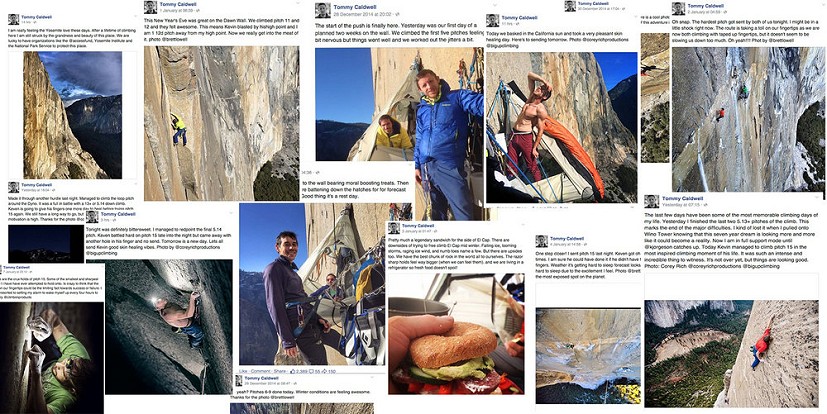

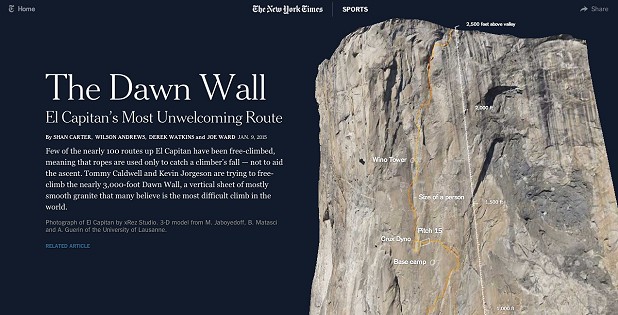

In 2015, Caldwell's first ascent of the 32-pitch Dawn Wall (5.14d) on El Capitan alongside Kevin Jorgeson captured the imagination of climbers and non-climbers alike – even Barack Obama was impressed. Thrust into the mainstream by inquisitive New York Times journalist John Branch, the story of two men forging the world's hardest big-wall route up a blank granite face 'using only their hands and feet' changed the course of Caldwell's life and had a major impact both on the climbing industry and public perception of the sport. Online engagement with climbing-related searches grew by 69% over twelve months due to Dawn Wall mania, while searches related to climbing walls rose by over 200%, according to research by digital marketer Adam Stack. Suddenly, Caldwell's face was appearing on news programmes, TV adverts and even cereal boxes.

Despite being in the glare of the spotlight, Caldwell hasn't let fame get to his head. He's a self-proclaimed introvert for whom the often sensationalist Dawn Wall media frenzy was not his natural milieu. A classic example of an unlikely hero, Caldwell regularly mocks his younger self in slideshows, juxtaposing an image of his former professional bodybuilder father, Mike Caldwell – 'a real life comic book character' – with an image of himself as a weedy, bespectacled youth. Perhaps the greatest, most fulfilling outcome of climbing the Dawn Wall, however, was the personal growth that Caldwell achieved through the process, resulting in reconciling differences with his father, meeting his wife-to-be, Becca, and becoming a father himself.

Caldwell's biography The Push is an unusually honest, introspective account of of persistence and failure both on the wall and in life in general. Relationships are a core theme in the form of a complex relationship with his body-builder father, a teenage union with Beth Rodden which fails to mature, the kinship with Kevin Jorgeson borne out of their dedication to the Dawn Wall project and the bond formed on becoming a father. The title takes on multiple layers of meaning as each chapter passes: an encouraging but perhaps occasionally pushy father, the decisive push exerted on Caldwell's militant rebel captor off a cliff in Kyrgyzstan, or the final push to complete the Dawn Wall's first ascent. Shortlisted for the 2017 Boardman Tasker Award, the book is a gritty memoir written in strikingly descriptive prose.

The eponymous documentary The Dawn Wall, following Caldwell and Jorgeson on their free climb of the route and delving into Tommy's dramatic backstory, was released in September 2018 and has since grossed over $1,200,000 globally.

Since the historic climb – repeated by Adam Ondra in 2016 - Caldwell has set multiple speed records on The Nose of El Capitan, culminating in the first sub-two hour record (1:58:07) alongside Alex Honnold in 2018. Four years since the Dawn Wall and now aged 40, Caldwell has two children with Becca. The family is currently on a year-long road trip touring the States in their van. During the 2018 Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival – where The Dawn Wall won the Best feature-length Mountain Film award - Caldwell took the time to answer some questions about his early life, the Dawn Wall experience and what the future might hold for him, using The Push to guide questions.

How do we build grit in our children? For my dad and me, it was a combination of bribery and exposure to minor traumatic experiences."

― The Push.

Growing up, your father – a bodybuilder and mountain guide - was, you write, 'a fitness freak with an outsize sense of adventure' while your mum was 'the classic wallflower'; two very different people. You seem to have gained positive qualities from each of them. You write: 'More than money or prizes, I was driven by the desire to impress my dad.' What effect did this have on you, growing up?

Yeah, both of my parents helped to shape who I am. I think my personality is very much more like my mom's but there is no doubt that I idolised my father growing up, so he was a very, very powerful influence in so many ways. He just created a lot of excitement in life - he's a natural leader so it's really easy to gravitate towards that.

You write that as a young child you used to stubbornly dig in the garden and try to reach China. 'For more than two years I dig [...] Somehow, some way, I am going to get there.' How much of that attitude do you think came from your father or your upbringing, or was it something innate that you were born with?

I think it was probably a combination of everything. I think I was innately born with that and, you know, I would say my mom is probably even more like that than my dad is. She's very focused and methodical. My dad is a bit more scattered, but he creates the vision, the dream. I had this goal to dig to China and that probably came from my dad. But the meditative aspect of being out there and just having my head down and working and being kind of anti-social, that came from my mom. Because really, a lot of that was just me being so inside my head and not wanting to interact with other people.

You had a compulsion to build things when you were very young, but building relationships was tougher, you write. Do you think that came about because you were so self-reliant and independent, and maybe you didn't need to rely on other people as much?

Yeah, I'm just a classic introvert. I gain energy when I'm alone and so that isn't necessarily good for the social aspects of life.

Your father introduced you to climbing and adventure, taking you camping in the snow at age 2 and guiding you up routes from age 3 onwards. He was a trad climber and mountaineer, but you write that he quite forward-thinking: he wasn't against bolts and he understood how beneficial sport climbing could be to progression. Did you ever feel differently about bolts, since many of your Dad's Yosemite friends were more traditional in outlook than your Dad?

Yeah, we definitely grew up in a community of people who were always bickering over ethics and chopping each other's bolts and it was all about drawing a circle around your ethical standard. That went for the majority of the people I was around growing up, the climbers at least. My father wasn't like that at all. He kind of appreciated everything, he saw what was coming next. We went to Europe and we went sport climbing there and he'd be wanting to bring a piece of that home, even though most of the community thought that was ethically a little bit funny at the time.

Because I knew more about climbing than the other students, for the first time in my life kids started to look up to me, even asking me to teach them[...] Climbing became another form of my education." - The Push.

You mention Yosemite pioneer Warren Harding holding court in your parents' living room in your book!

Warren Harding did a slideshow at my house when I was quite young, so I met him but he wasn't part of our community per se because he lived in California and we lived in Colorado. But our community was comprised of the guides of the Colorado Mountain School, the local guiding organisation where both of my parents worked. I had a lot of guys to look up to. But they were real dirt bag climbers - you don't make money from guiding in the United States. So they all lived out of their cars, but they were super fun. Fun, dirtbag climbers of that era.

You were a competition climber for a period and you write that being the best at something, was like a 'tempting elixir.' You explain that when you were younger you were quite small and not as developed as other children, but then you found your niche in competition. However, you started to struggle a bit when you got older as a teenager, with a younger Chris Sharma pushing you. What do you put that down to?

I think I always had this self-consciousness from a very young age because I just felt like a failure. I wasn't intellectually very advanced. I had learning disabilities and so climbing provided something that I could be good at when I was really young. And then, when I started to fail there too, I suppose that that hit me harder than it might hit somebody who just had a more healthy sense of self-worth, I suppose. But I don't know, I think that self-consciousness has maybe been pretty good for steering me in the right direction. I've always looked at the things that I could excel at and focused on those, and that's served me quite well.

He turns sharply toward me. Our eyes lock. I lunge for the strap of the gun slung over his shoulder. I pull as hard as I can and push his shoulder. His body arches backward through the blackness, outlined by the moon. He cries out in surprise and fear. His body lands on a ledge with a sickening thud, and then bounces toward oblivion." - The Push.

Aged just 22, during a climbing trip to Kyrgyzstan in 2000, you, Beth Rodden and two companions were kidnapped by armed Uzbek rebels at war with the government. You write about the trauma of this event, describing a troubling realisation that you had the capacity to kill a man, despite not actually killing your captor when you pushed him over a cliff edge in order to escape. In The Dawn Wall film your Dad mentions that your personality changed and that you became highly insular. Can you describe what this period was like?

In your relationship with Beth Rodden you were described as the first couple of climbing. You had a high level of media attention post-Kyrgyzstan. What was that like for you to deal with?

God, man, that's a pretty complicated question, honestly! The media attention with Beth basically started when we got kidnapped in Kyrgyzstan, which was very contrived, because we were a professional climbing couple who came back from this crazy experience and then the media surrounding that was mostly a conspiracy theory after one guy thought that we had made the whole story up and he had a mission to prove this "hoax."

So it made me very sceptical of the media in a lot of ways. It made Beth withdraw from it all, so the fact that we were in the media was almost unwelcome, in a way. We really liked to excel in climbing and we liked to have this sense of mastery, which meant that we kind of got "famous" in a small way, but it was never our safe place. I was never that comfortable with that.

Dad always taught me that it's not what happens to you, it's how you deal with it."

―The Push.

Beth retreated from climbing. She wasn't ready to get back into performing like she used to, whereas you went the opposite way. You felt like you had to get back into it and you made the first free ascent of the Muir Wall, describing your ascent as 'another step toward normalcy.' Was big wall climbing a form of therapy, in a sense?

I think Beth thought climbing was the reason that we went through what we did in Kyrgyzstan. I didn't think that so much, and climbing was always the place where I gained strength, so of course I gravitated towards climbing. And just being that introverted young kid, just being in the mountains alone or with Beth felt like the right place for me, yes.

Your divorce had a similar effect in that you write about how perception affects experience, similar to how Kyrgyzstan changed the way you perceive things; your way of thinking about difficult situations and how to overcome them. You jumped back into climbing - mostly alone. It seemed as though Yosemite's walls were once again a kind of salvation for you at this point?

Yeah, I think after Kyrgyzstan I spent about a decade going to El Cap and just free climbing all the existing routes. It was a wonderful period of my life and I felt so much progression and success and it was such a great thing. So then when things got dark again after my divorce, of course I kind of gravitated towards the positive aspects such as my curiosity about where I could take things physically. I combined that with my introverted nature and went out and just suffered in the mountains alone. That's what the Dawn Wall represented in the beginning, really.

Panic flooded my mind: How can I climb without a left index finger?" - The Push.

You lost most of an index finger in a DIY accident. You write that you had to become a more cerebral climber to overcome the disability. In what ways do you think you became more cerebral?

I think before I lost my finger I relied on my experience, since I'd been climbing from such a young age, so I sort of took for granted the fact that I could go out and climb quite well without really thinking too much about it. I'd train a bit, but I never really tried to analyse how I could be the best. And after my finger incident, I was like, well, climbing could be gone for me, at least in the capacity and at the level I'd been operating at. I thought I might not be able to climb full-time anymore and I wanted to go on all these trips all over the world.

I thought 'I have to go all in now if there's any chance of me continuing this life.' So I started analysing diet and training and then I started analysing body movements. So those are the cerebral aspects you're talking about.

You write about Alex Megos, explaining that you watched him train and consequently started to treat training 'like a full-time job' while working The Dawn Wall. Do you think if you had trained in that way when you were younger, you might have lost interest? You seemed to be more passionate about the adventurous aspects of climbing when you were younger.

I might have been so into training that I wouldn't have gone into adventure climbing, I suppose. Yeah, people like Alex Megos and Jonathan Siegrist - in my mind they represent this new school way of thinking. The Brits have been doing it for a long time, where they train very scientifically. But that's just not the way we used to do it in the US. And I think I'm starting to understand that that stuff just really works. And it can even be quite fun because you feel yourself getting stronger. So that's what brought my fitness level up to what enabled me to do the Dawn Wall in the end.

It was interesting the different approaches that you and Kevin had to social media on the Dawn Wall where you say your approach was 'send first, spray later,' but it didn't quite work out that way. Kevin seemed much happier to keep up the online persona, whereas you write that you accidentally dropped your phone from the portaledge. Did you really drop your phone, or was it deliberate?! How comfortable were you with the ever increasing interest online?

What a circus. I say nothing. And then, before I know it, I'm fully wrapped up in surfing the web, mouthbreathing at my screen. Wait a second, this is so messed up!" - The Push.

New York Times journalist John Branch took an interest in the story, which proved to be a turning point. Do you think there would still have been the same interest had he not started documenting your ascent?

I think if it were not for John Branch and the New York Times the media scene would have looked very, very different. They created the viral nature of the climb from pitch 14 or 15 onwards. And yeah, I think he helped people understand, including me, that climbing actually can make for a great spectator sport if the stories are told in this long-form way. I mean, if you think of something like the Olympics, one of the reasons it's so cool is because you're following it along for a couple of weeks and you're wondering which country's going to win and there's a decent duration of time.

We did that on the Dawn Wall without even planning it. We were up there for a couple of weeks, and people got emotionally invested. John Branch showed this to the world - and even introduced it to the world - and they followed along.

Suddenly you were in the limelight on the wall, but you write that you felt like your 'bubble of intimacy had been burst' and you also had the film crew there. What was this experience like?

The film crew alone wasn't that weird for me, actually. They were part of that bubble of intimacy because they're guys that I've been doing projects with since I was really young. They were like my best friends. But when the media, the larger, mainstream media started to show up, the news trucks, the people walking and waiting on top - that was when the bubble burst.

You write about how after Pitch 15 when Kevin started to lag behind the media were speculating about what would happen if Kevin didn't do it. Did that add a lot more pressure?

The speculation about Kevin not doing it didn't bother me so much. It was the fact that they were just getting everything wrong factually. Nobody could differentiate between free climbing and free soloing and they would say that we were climbing on El Cap, but they would then show a picture of Half Dome and it just seemed like nobody cared about the details, so that was a little bit hard to see.

But I think it did add pressure, and interestingly, I think it was very motivating for Kevin. He operates quite well when there's a tonne of pressure on him, and they created the tonne of pressure.

Even in physics, matter behaves differently when being observed."- The Push

Did that have any echoes with Kyrgyzstan with the media distorting facts?

Yeah. I mean, it felt very different because Kyrgyzstan was negative media in a lot of ways and the Dawn Wall was purely positive, like very positive in this overwhelming way. I think what Kyrgyzstan taught me, or at least the media aspect of Kyrgyzstan, is that there are always going to be a few lunatics out there and if you spend your life worrying about them it's just not a good way to live.

I still never loved the media aspect though. It's always sat a little bit sideways with me even though it's created a lot of good opportunities in my life.

You didn't really know Kevin that well beforehand. He was more of a boulderer. You write that you developed a brother-like bond and that you were really proud of him. Did it feel in some way like you were a father figure leading him up the wall because you're a bit older than him and he was less experienced?

Pitch 15 was the first to break the pattern, you write, and you were wondering whether you should wait for Kevin, or climb ahead. Then everyone was watching. How much pressure did that add for you at that point? You were rejoicing in your own success, but you also didn't want to celebrate too loudly, I sense?

I didn't feel stressed about my own ascent at that time. I felt a bit stressed for Kevin, but the decision to wait for him up there on the wall felt so utterly right. When the decision hadn't been made, everything was quite heavy. But once I was just like 'I'm going to wait as long as it takes', it just felt right. And the best thing I could do at this point was try and take some of the pressure off Kevin because he was basically chewing his fingers down to little nubs as he was so nervous!

I just had to bring the party up there, and it did make it fun. I'd dropped my phone, which meant I was enjoying the view instead of going on social media. Overall, the situation for that week when I was waiting for Kevin was quite nice, actually.

Before topping out, you were quite uncomfortable because there were strangers on the summit and you weren't sure how to deal with them. You write that you just wanted your wife, Becca. What was it like when you topped out?

I desperately want to hold on to this experience. My body and mind came together in a crescendo of meaning that was years - more than years, decades, my whole life - in the making." - The Push.

You write 'If Kyrgyzstan was [your] storm, maybe the Dawn Wall was [your] wave.' Can you explain this in more detail?

I think that Kyrgyzstan created the ripple effect that led to me climbing the Dawn Wall. It started the series of events that led to me believing that I could climb something like that and wanting to dream big, feeling like every day had to be lived to its fullest. The Dawn Wall was really a way to try and make every day count because I was doing exactly what I wanted to do and I was in the most beautiful place. It also created the strength I needed in a lot of ways - the resolve and mental fortitude.

I mean, honestly, I didn't know … I've always felt that way but I didn't really know exactly how it played out or how to describe it. Writing my book was an effort to try and figure that out a little bit.

You and your father experienced difficult times relating to one another emotionally during your teenage years and post-Kyrgyzstan, as two very 'macho' men driven by success. Your father said he didn't feel like he could meet you at the top because it was too much for him. How did you feel about his absence at the summit of El Cap?

No, he's not very good at showing emotion so he didn't have to show emotion, in a way. He just got to closet it for a while by hanging out in the valley. It's funny, he's emotional in a positive way. He's very loving and happy and gregarious. But more difficult emotions are something that he struggles with. I wish that he could have been there to share in that moment, but he wasn't ready. Actually, having him read my book was a very, very hard thing for him because it just kind of exposed the hard emotions in a way that he's just not comfortable with.

The Dawn Wall film was originally just going to document The Dawn Wall and not your life story, but in the end it was based around your book. How did you feel about this?

The filmmakers were critical readers of my book and originally when we were talking about the film it was just going to be about the Dawn Wall. But I always felt like there was so much to say … that the more powerful story would go beyond the Dawn Wall. So that's how I wrote The Push and I think after reading my book, the filmmakers realised that that was the way it had to be.

Maybe all along the appeal had lain in the satisfaction of giving fully of myself. Maybe climbing wasn't always the answer, but the venue." - The Push.

What was it like watching the film, since you wrote the book with Kelly Cordes and had a lot more control over that than the film? You said you watched the film at the premiere for the first time. Did you have a lot of trust in the filmmaking team?

Yes, I mean, I've worked with Josh Lowell and Peter Mortimer for 20 years, and every time they've told a story of a trip or an experience that I've had, it's really fun to watch. You know you can trust somebody when they do that over and over again. Plus, I had just written my book and I tried to put myself in their shoes, since when I was writing my book I didn't show it to my parents, I didn't show it to many people - it was just me and Kelly because I felt like showing it around would impede creativity and it wouldn't make as good a final product.

So when they were making the film I told the team, 'I think you guys just need to be free and I trust you.' I was quite worried before watching it. I was like, 'Oh, I wonder what they did with my story.' I mean, it's quite an exposing thing that a lot of people will see - but I was very happy with it.

You write that you thought you only gained true fulfilment from being in the mountains, but then you realised that the 'act of creating' things, like the book, talking to audiences, is what you find most deeply rewarding. Can you expand on this?

Yeah, I think I have discovered that in recent years. It's the creative side of things. It's taking something that you feel very passionate about and spending a lot of time trying to make it into whatever that end goal may be. Writing a book, strangely, felt very similar to climbing something like the Dawn Well for me. It took a lot of obsession and it was very emotional and it went deep, and that's kind of where the fulfilment comes from. I think anything that's hard creates movement and creates change in our life, and I'm all about progression.

While I used to focus on what I could gain through experience, I am now thinking more about what I can give." - The Push.

You explain in your book that now you're in the teaching stage of life, focusing on 'giving fully of yourself.' Why is this important to you?

At least for now I'm trying to focus on things that aren't so much about me. I've written a book about myself and this movie came out about my story so in some ways I'm sick of it all being about me. I'm looking to figure out how to take any wisdom that I might have gained and pass it on, for better or for worse - hopefully, for the better. The advocacy work is an opportunity right now, I guess. I've got a bit of a pulpit and if I don't use that for some greater good, what's the point of it, really?

So if I feel like I can move the needle a little bit on the things politically that I feel strongly about, like protecting the environment, I might as well do that. Definitely I have no want to be a politician! But utilising climbing, it's something that people are starting to realise works. Like using "famous" figures to talk about issues actually does work. So yeah, I should do it!

Fame also brings opportunities from big brands and you joined forces with a beer company, which people online were quite critical about on social media. How did you feel about that? How do you approach this, when people come to you with things that you're maybe not 100% sure about?

What's it been like for you having two climbing films in mainstream theatres at the moment? You and Alex are both climbing on the same piece of rock! It's quite a coincidence. Did you expect to have two big films out at the same time?

I don't think anybody wanted both films to come out at the same time. It just happened to be that way. The guys just took a long time to finish their film. I think they are very happy with the film, but if you asked them if they have one regret, they'd say 'I wish we could have gotten it down a year earlier!' to spread them out a bit.

But I'm not certain that it's all a bad thing. I think that the films probably play off each other. It's like if you go see a Marvel movie, you want to see it more often, and so I think there's a bit of that happening. And it's created this thing that it just feels like a moment in climbing right now. Suddenly climbing is being watched by a very large group of people in a way that it hasn't been in the past, because it's in major theatres in two movies and I guess that's cool.

Maybe we can view risk like we would a drug, beneficial to the organism in the proper dose," he once wrote. "Too much or too little may be harmful." - Quoting Tom Horbein's 'Everest, The West Ridge' in The Push.

Since the Dawn Wall, you've claimed The Nose speed record on El Cap alongside Alex Honnold multiple times. Last summer, Kelly Cordes wrote a piece for Outside magazine, titled 'Even Tommy Caldwell Questioned the Nose Speed Record' when multiple accidents and deaths occurred during this style of ascent in Yosemite, and you were setting your records. Can you explain what your reservations were, and how climbing with Alex might change your perception of risk?

You mentioned in interviews at the time how Becca and your family were more worried about the speed ascent than the Dawn Wall. How do you go about justifying what you're doing? Is it hard to justify that to your family?

Yeah, it's almost impossible to justify highly risky things to my family and so they make me second-think it all the time. If I didn't have my family, I probably would be going on big Himalayan expeditions, I'd be climbing very snowy things - that's an environment I love and I feel like I thrive in it, but it's just too dangerous. I can die. But sometimes, the sexy appeal of it draws me in. It's as though I'm a drug addict and I want a hit - occasionally I take a little hit and I feel bad about it afterwards.

My parents didn't believe in spoiling their kids with material goods, but lavishing them with the opportunity to fully experience life was part of their parenting." - The Push.

Having children has clearly changed your outlook on risk and you spoke in Banff about teaching values to your children, and mentioned that writing the book made you look very closely at your own childhood. You're also highly thankful of your parents and how they brought you up. What kind of values do you hope to pass on to Fitz and Ingrid?

You've got a son and a daughter, do you feel it's especially important for Ingrid to encourage her to climb and get outdoors as our community tries to encourage more women into the outdoors?

Yes, in light of the Me Too movement especially. It's all about women power, so I look at my daughter and I think 'We must find a way to make you strong. There're so many evil men in this world and we've got to make you strong.' My daughter, just the way she is, she's so lively and I can tell already she's going to embrace and absolutely love the outdoor adventure culture.

My son, he's actually way more cerebral. But he also loves it, although I won't be surprised if he turns out to be more of an academic or something!

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

- ARTICLE: Alexandr Zakolodniy - A Climbing Hero of Ukraine 26 Apr, 2023

Comments

Good interview but the "multimedia" format is a resounding NO from me.

I think the mixed format style works well here as it is a long interview.

likewise, I started to read this in my lunch break on a PC with no sound only to realise that there were audio clips. Guess I'll have to come back to it later

"That's what the Damn Wall represented in the beginning, really."

is that a [sic] or a typo - good one ....

We'd be interested to hear your reasons for disliking the format.

Doug: It's made clear at the start that it's a multimedia piece and other websites don't tend to have any sort of video warning. Perhaps work isn't the place to be browsing UKC ;)