An Instagram account Climbers Against Dick Pics (@chossyDMs) prompts Natalie Berry to investigate the harassment faced by climbing athletes online. As the climbing community grows, are climbers receiving more abuse? How do experiences of abuse differ between men and women?

The direct message icon flashes blue. It's not from an account I follow. Instead, I have another Instagram message "request" from a profile I'm not connected with. That in itself is no crime; I frequently post journalistic appeals in my stories. I'm asking for it, so to speak. But I'm nonetheless reluctant to tap on the icon.

Social media abuse, cyberbullying and online sexual violence are hot topics in the #MeToo era; the great irony of the 21st century being that social media lends itself to antisocial behaviour in myriad forms. Parody accounts, memes and nasty comments are open for all to see, but the direct messaging feature present on nearly all forms of social media enables explicit material to go comparatively unchecked - for the recipient's eyes only.

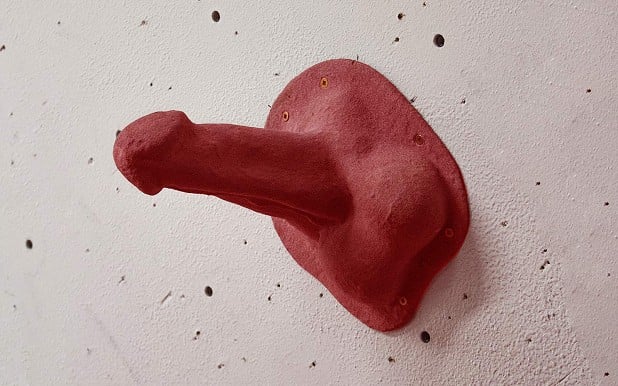

An Instagram account Climbers Against Dick Pics (@chossyDMs) was recently launched by top female climbers in the US as a defiant rebuke to the individuals who send abusive and/or sexually inappropriate messages and images via private messaging on social media. The screenshots of the weird and often not-so-wonderful messages received by the account's instigators - and examples sent in by its followers - are exposed, providing an illuminating insight into what some climbers in the public eye are faced with when their inbox icon glows blue.

I think it's all a lot easier for me being an adult male. I don't envy what some of the young women in the community must get. - Alex Honnold

Internet abuse in the digital era is, of course, not specific to the climbing community. Celebrities, politicians, grandmothers, and girls next door have all likely received unwanted attention on social media. People with a high public profile, however, are arguably more at risk of attracting unwanted attention. As climbing lures in more pairs of eyes with its boom in popularity at a time when society seeks to highlight and stamp out sexual misconduct, I wondered if those in the media glare are increasingly becoming targets for abuse.

'That's got to be spam, or a bot!' came the response of a male friend to a strange message from a stranger. 'Why would anyone in their right mind send you that?' The phrase 'in their right mind' is important to acknowledge. I don't doubt that some atypical communication is attempted by people with mental health or emotional development issues. We are not all capable of socially acceptable interaction and understanding this is key. Sifting innocent attempts at conversation from malicious behaviour can be a nebulous task; a tangled web of gut feelings and guesses. Sometimes there's a knotty overlap. Distinguishing between a harmless fan and sexual predators sounds simple, but in reality it's a sliding - and very slippery - scale. Internet anonymity can fuel a confidence not easily possessed in reality due to a phenomenon psychologists refer to as the online disinhibition effect, and typically shrouds perpetrators from identification or repercussions.

My friend's immediate apportioning of blame onto some faceless, automated system rather than onto an actual living, breathing human with a brain spoke volumes to me. As recipients of such messages, we know that more often than not, there's a face behind the username, and considered, entitled intent behind the message. In the majority of cases, disowning human responsibility and placing blame on bots enables the perpetrators; abusers dehumanise their victims and society dehumanises the abusers.

'The messages go from, "Hi, you are an inspiring climber!" to, "Fuck you bitch!" very quickly if you don't respond.'

'Definitions of sexual violence vary in specifics, but generally acknowledge that sexual violence is about exerting power and aggression (not sexual desire) over someone else in order to undermine an individual's sexual or gender integrity,' sociology professor Jordan Fairbairn writes in the 2015 book eGirls, eCitizens. 'Online harassment is understood as a form of sexual violence in part because of the emotional distress and breach of an individual's sense of safety. Moreover, when people's safety and integrity is compromised online, they are marginalized and/or pushed out of these spaces.' Advocates for categorising sexually violent messages as sexual violence are, according to Fairbairn, 'working against a strong social current of resistance (e.g., "But he wasn't actually going to rape her").'

Online sexual violence not only harms its victims, she argues, but it also bolsters what is now understood as a 'victim blaming' culture in which sexual abuse and harassment is expected, tolerated, and/or encouraged, and women and girls are held responsible for their safety and blamed for their victimhood. 'These conditions are now widely characterized as rape culture and online environments are part of this culture,' Fairbairn writes.

Historically, sponsored athletes in mainstream sports - male and female - have endured cyberbullying, overenthusiastic fans, stalkers and racist, sexist and homophobic abuse. Sports stars are among the most revered celebrities in the world, but little research has been done into the online abuse experienced by athletes. A 2015 study by Bournemouth University developed a typology for understanding virtual maltreatment in sport.

'Virtual maltreatment refers to direct or non-direct online communication that is stated in an aggressive, exploitative, manipulative, threatening or lewd manner and is designed to elicit fear, emotional or psychological upset, distress, alarm or feelings of inferiority. Virtual maltreatment can be classified as physical, sexual, emotional or discriminatory in nature.'

The researchers argue that alongside parents, coaches, and other athletes, fans should also be added to the list of potential perpetrators, despite their role as reverent followers. Although lagging behind the mainstream sports such as football, tennis and athletics in the celebrity stakes, outdoor and adventure/lifestyle athletes including pro US skier Caroline Gleich have spoken out about online harassment.

I send emails to climbers of both sexes who have the biggest social media following. There's the elephant in the room to consider: the high likelihood that the majority of messages received by a female will be from males. This is true of my own experience, but what about those with a bigger profile? Does the content they receive differ? Do male athletes receive weird stuff too?

'The inappropriate comments tend to come from men. I've had a couple where they've asked to date me or take me on romantic trips to crags,' Emma Twyford explains. 'I try not to ignore stuff but I tend to reply politely just to say I'm with someone and they've generally been apologetic and said I'm lovely.'

'The flirtatious comments I get are more often from men, which is obvious, I suppose,' Hazel Findlay tells me. 'Someone sent me an email once asking if I had a boyfriend. I replied to that curtly just saying that I did. However, the negative commentary I've received in comments to some of my more opinionated posts have mostly come from women.'

'I definitely receive more inappropriate content from males,' a female pro climber writes back. This athlete was also subject to extreme cases of stalking. 'I've had photos sent to my home for me to sign. Obviously I don't share my address, so this was really alarming,' she says. 'I've also received emails and calls from prisoners. Again, my email is online, but I don't give out my number. I discovered that he was a sex offender in prison for child sex abuse.'

As climbing grows, sponsored athletes unsurprisingly appear to be receiving more interest and attention from increasing numbers of followers. 'Initially the only people messaging me on social media were climbers,' a sponsored female explains, 'but as the sport grows, climbers and non-climbers message me. I now get more messages than ever before.'

Climbing husband and wife team, Caroline Ciavaldini and James Pearson struck me as an interesting example to look into: since they're a couple in the public eye with a joint Instagram account, does Caroline receive as as many messages as women with their own personal accounts? Although this is tricky to quantify, she nonetheless receives messages directed at her through their combined pages. 'Most of the negative interaction I've seen, on our account, is male to female oriented,' she explains. 'Every now and then I receive messages with sexual content. Once I was even sent a photo of a penis,' she adds.

It's worth noting that a couple of female climbers politely - and understandably - decline to take part due to ongoing trauma brought on by online exchanges and stalking.

Intimidation as the highest form of Flattery

The advent of Chossy DMs curiously coincided with some unwanted attention through my own profile. It began with simple, emoticon-only messages sent as requests from a stranger through Instagram. Due to these 'request' messages being tricky to find, I hadn't noticed them initially. Around five messages had been sent by the time I discovered the 'conversation' thread. 'Are you OK lovely? If you need a chat, just give us a bell :)' followed by 'You seem cool, if you wanna hang out, let us know.' I ignored the messages, knowing that Instagram hides the fact that messages have been seen until you allow the person to connect with you.

An invite to climb in a specific location followed, as well as praise for my work. I continued to ignore the messages, watching this one-sided conversation continue each time I posted a story, when the messenger would send another emoticon comment. The following week, having ignored them on Instagram, my persistent pursuer followed me on Twitter and began interacting. Still non-responsive, a few days later they added me on Facebook and began liking my posts - perhaps the most intrusive of these acts, seemingly coming as a last act out of desperation to hear from me. I stopped posting for a week and the contact seemed to end, before a salvo of five messages hits my inbox in one day. I now have almost 30 messages, none of which I have responded to.

Nothing that this person has sent me is threatening, aggressive or abusive, but the persistent attempts to grab my attention through every possible online avenue and respond to them is nonetheless worrying and if nothing else, highly irritating. I'm well aware that I could block this person, but part of me wants to keep an eye on what they're thinking. If they realise they're blocked, will that make the situation worse? Will I unintentionally escalate the situation by trying to resolve it? This is a question familiar to women: do I smile and go along with the unwanted flirty comment, or do I ignore it, or even rebuff it? How will the commenter react?

My concerns are validated by the experiences of a top female climber. 'I have definitely had messages become more aggressive because I ignored them,' she tells me. 'The messages go from, "Hi, you are an inspiring climber!" to, "Fuck you bitch!" very quickly if you don't respond.' Even with the distance and disconnect that virtual interactions provide, these interactions can be as intimidating as face-to-face encounters. 'Remember that online spaces are, for many, deeply integrated with work and/or educational experiences and institutions, as well as social relationships generally, and the boundary between offline and online is increasingly artificial,' Jordan Fairbairn reminds us in eGirls,eCitizens. The choice of the word "request" seems tragically appropriate considering the purpose for which direct messages are increasingly being used, as a means for demanding attention; an inbox imposition.

My social stalker is a common theme amongst female respondents. 'I have a few followers who seem to comment on every single post and they are always a little weird, slightly inappropriate but nothing too serious,' one woman tells me.

'It seems obvious that more people climbing means more people who don't know how to behave on social media,' says Hazel Findlay. 'I don't receive many inappropriate messages publicly, just in the DMs which I rarely look at,' she adds. Fair enough, but how do we deal with it? Hazel takes a pragmatic approach. 'If people are suffering from abuse on social media, they need not do so,' she says. 'All the platforms have settings which enable you to either not receive any messages at all, or block people. I see no reason at all to interact with idiots who don't know how to behave. When I get an inappropriate message, it doesn't bother me at all. I don't think it's very nice and I don't condone this behaviour, but I don't allow it to affect me.' Likewise, another female athlete chooses to ignore and delete. 'I generally delete and block any undesirable messages,' she says. 'Sometimes I tell people they are being inappropriate, but my go-to action is to delete/block people, which occurs roughly once or twice a month.'

Boys will be Boys

Considering that the majority of responses demonstrate males sending inappropriate material to females, I was keen to hear what kind of interactions male climbers in the spotlight experience. Most responded saying they didn't have much to say, given that they receive minimal abuse, but that in itself was illuminating. I attempt to find a balance between the genders in this topic, even when the scales are tipped towards women bearing the brunt of online abuse.

With 1.4 million Instagram followers, undoubtedly the most high profile climber at the moment - and of all time, perhaps - is Alex Honnold, whose public profile recently burst far out of the climbing microcosm and became truly global thanks to the film Free Solo scooping an Oscar and attracting mainstream media attention worldwide. Alex's audacious solo ascents are well-known both within and outwith the climbing community, but you only have to glance at his latest social media post to see the impact that Free Solo's recognition has had on his social reach. Hundreds of comments belatedly congratulating him on his El Cap free solo ascent show that his name is entering the consciousness of non-climbers worldwide. Interestingly, aside from the sensationalist comments accusing him of being a reckless daredevil, Alex reveals that negative social media comments since Free Solo have generally been directed at his girlfriend, Sanni.

'I get very few truly negative messages, and I don't think I've ever gotten anything inappropriate,' Alex tells me. 'I get criticism but it's generally fair enough - criticising risk taking and such. Now it's mostly people making fun of Sanni after seeing Free Solo, which is worse because it's more mean spirited and she takes it harder. But even those comments are mostly just snide little remarks - they don't really matter.

'I think it's all a lot easier for me being an adult male. Many fewer f*cks given... I don't envy what some of the young women in the community must get,' he adds.

German sport climbing star Alex Megos is in a similar boat. 'I don't really get a lot of weird messages and I usually delete everything from people I don't know, anyway,' he explains. 'There are occasional messages from girls: "Hi <3." That's it for most guys I think.'

Male climbers in the public eye are certainly not immune to flirty comments. Despite receiving far fewer replies from male climbers - possibly because it doesn't affect them to the same extent? - I do some highly unscientific research on their public photo comments, which mostly reveals adoring platitudes. 'Is he single and ready to mingle? ;)'; 'Oh good Lord he's a thing of beauty!;' 'He needs to climb his way into my heart!' along with heart emoticons and tagging friends to give them a glimpse of the eye candy. In parallel with the female accounts, the images with the most flesh and faces on display seem to attract more likes - sometimes thousands more.

Dutch all-rounder Jorg Verhoeven mostly receives what appears to be spam. 'Privately, I get some suggestive offers from sexy-looking 'female' accounts that I believe are actually bad-looking men.' Navigating the weird world of DMs can be challenging, he explains. 'It's hard to distinguish between someone who is genuinely giving feedback and others that just go: "Hi, how ar you? Will you be mi frend?"'

'I feel we need to be adult and non-naïve about the unwanted stuff,' another male pro climber says. 'Of course it happens. It's kinda bloody obvious that it does.' Despite his equanimous tone, this respondent goes on to tell the story of an unsettling experience with a stalker. His nonchalant acceptance that this 'stuff happens' is perhaps part of a toxic culture of victim blaming, to which myths and stereotypes contribute, Fairbairn writes in eGirls, eCitizens. 'If we assume that online violence can be ignored, walked away from, and/or is something that people cause or deserve, then we will continue to hold people responsible for the abuse and harassment they experience.'

As the focus of the #MeToo movement broadened from disgraced celebrities such as Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby to the everyday experiences of women around the world, American writer Lili Loofbourow wrote about an inevitable societal 'attempt to naturalize sexual harassment. "If there are this many men doing these things, then surely this is just how men are!"' Should women just 'shut up and put up' with it? A corollary argument of this attitude is that women must be actively appealing for this attention, and be grateful for it, since we are all sexual beings...

Sex sells

Sportspeople at the top of their game are often fit and attractive - many of them are well aware of this fact. Are they asking for it?

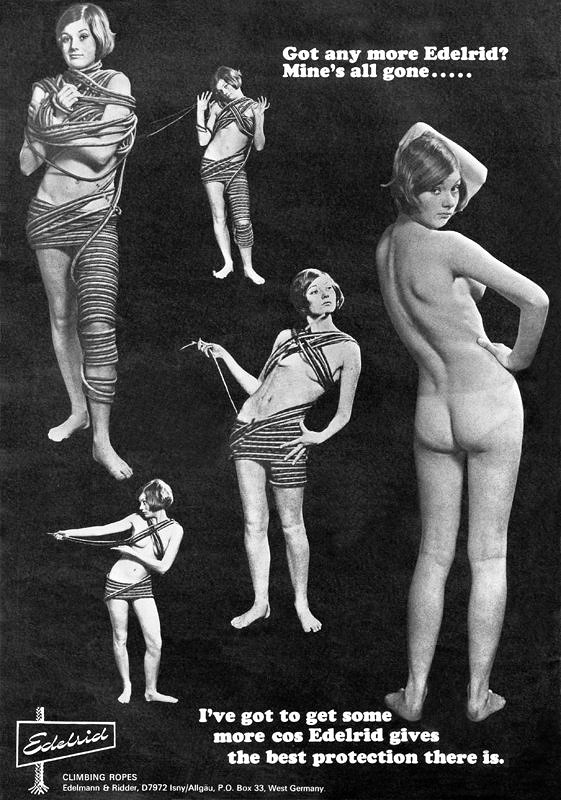

In a UKC article analysing about the portrayal of women in climbing media from 2005, Mick Ryan wrote: 'Such is the dilemma of images of women where at some level they exploit, on another give pleasure, on another celebrate, on all levels sell, and on another darker side feed the myth that women are the tools of men which can ultimately lead to violence and in some cases lead to death.' Ryan references some questionable advertising campaigns at the time promoted by a climbing brand involving scantily clad women in sexually suggestive contexts, which today would likely be called out online in seconds. In those days, climbing media was restricted to printed publications, websites and branded advertising material and the image of women in climbing was wholly dictated by brands and the media. Threads on online forums titled 'Hot Babes Who Climb' or similar were commonplace, where multi-page discussions shared images of female climbers ranked by looks, ridiculed and above all - objectified.

As liberating as social media can be, there remain the old adages that yes, 'sex sells', and 'a picture is worth a thousand words.' It's 2019, and we live in a confusingly fractious time where society is at once hyper-aware of and sensitive to equality, gender politics and #MeToo scandals, but where we simultaneously uphold ideals of beauty, behaviour and continue along down the dangerous course of sexualising young girls and women. Although female climbers have more agency than ever before in controlling their image, the 'dilemma' described by Ryan remains true: no matter her climbing merit, an image of a female climber can always be turned into a commodity - especially if she conforms to conventional standards of beauty and especially if she is wearing practical clothing. 'Practical' often manifesting itself in sports bras, tight lycra and skin on show. Practical is also - conveniently - titillating. Herein lies another paradox: women can both assert their sexuality and be sexually objectified at the same time. Subject and object. Schrödinger's pussy: at once a passive conquest and a feisty feline that 'grabs back.'

Schrödinger's pussy: at once a passive conquest and a feisty feline that 'grabs back'.

Female athletes face a quandary: be yourself, climb hard, be sexy and gain likes, followers and the unwanted comments, or play staid, let achievements speak for themselves, forego follows for sex appeal and potentially miss out on opportunities. Or some other combination of these myriad options. Meanwhile, in a frustrating double-standard, men can be topless, wear a t-shirt, shorts and not have to worry too much about the potential repercussions of their choices. 'At my glummest, I sometimes think women get to choose - between being punished for being unsubjugated and the continual punishment of subjugation,' wrote Rebecca Solnit in Men Explain Things to Me. We're damned if we do use our bodies, damned if we don't. Equally, though, being female - and being attractive and female - undeniably brings advantages. Advantages over other women, advantages over men - because sex sells, and women are highly marketable, especially in 2019. As depressing as this may sound in the #MeToo era, there's no denying the fact that brands and many women are benefitting from the focus on female empowerment as the lens pans wider. In shifting the spotlight onto women, a key question remains: are we selling women to women, or women to men?

All about the Money Shot

Jorg Verhoeven recognises this dualism in the hype surrounding women's climbing. 'I think the topic of social media abuse is strongly related to the fact that we live in a sex-focused world, where women receive abuse, but also sometimes (much more rarely) the advantages,' he says. 'By no means am I saying that women are asking for this stuff, but some probably know that their success is largely due to sex appeal.' The same applies to a smaller extent to some male climbers, who have gained the unlikely status of a male climber 'sex symbol': Chris Sharma, who has featured in Ralph Lauren fragrance adverts, and Alex Honnold, who has graced the covers of magazines in topless poses. Undoubtedly, though, in the case of these male athletes, their achievements carry more weight than their looks in creating opportunities. The instances in which sex appeal has bolstered a male climber's status and success aside from his climbing merit are few and far between compared to their female counterparts historically. Lynn Hill, Catherine Destivelle, Isabelle Patissier - these golden girls of the 80s possessed the 'double threat' of top-end talent and beauty, which attracted brands and TV producers like flies around honey.

Today, the situation remains, albeit with a larger pool of highly talented female climbers and more money and opportunities. Controversy abounds with comments online criticising particular athletes for selling out, or for their good looks trumping their climbing abilities. Does someone deserve to receive a sponsorship largely based on their appearance and social media persona? How low a grade does a woman need to climb before her smile can sign the contract? How hard does she need to climb if her looks aren't conventionally marketable? It's a nebulous situation: is this actually happening? Are brands really so shallow? Who's losing out here, if anyone? It all feeds into the 21st Century model of capitalism.

In a 2015 post on his blog Evening Sends, Andrew Bisharat wrote about the 'athlete/model' conundrum. 'This type of hyperbolic conflation of image and substance is becoming much more common. It's so rampant these days that we don't even realize that once upon a time being a professional athlete had to do with athleticism, not recognition or fame. Now, it's the other way around: athletic recognition is the byproduct of popularity.' Adventure sports can be 'sexed-up' and framed by brands to promote the lifestyle aspects of the activity just as much as the athletic feat - think #vanlife, #travel, #adventure - in a way that eludes most mainstream sports. It's ironic, considering their 'dirtbag' roots, but this sellability of both climbing and the attractive people who partake in it is pertinent, perhaps, to explaining the growing objectification of climbers as 'products.'

Jorg Verhoeven has a theory as to why athletes are increasingly receiving more abuse from followers. 'I think that respect towards each other has probably gone down, while expectations towards pro climbers have gone up - as in, I, the consumer, pay for your salary, so you're my bitch', he explains. 'I believe 20 years ago high profile climbers were evaluated by their ethics in climbing, but today they are judged by their ethics in life.'

The advent of social media has enabled athletes and amateurs to take an influential medium into their own hands, curating their own content and publicising themselves by choosing what to post and what not to share. This has arguably benefited professional climbers - especially females - through being able to sell themselves. On the one hand, social media has resulted in an empowering market shift, leading to increased visibility of women in climbing and giving both men and women the freedom to portray themselves as they wish; on the other, it leaves people open to criticism and abuse through direct contact, and perhaps lends excessive power to the image in a visually overstimulated society.

'Women-as-bodies are sex waiting to happen – to men – and women-as-people are annoying gatekeepers getting between men and female bodies, which is why there's a ton of advice about how to trick or overwhelm the gatekeeper,' wrote Rebecca Solnit in a 2018 Guardian article on the commodification of women and sex. The torrent of online abuse faced by female athletes is perhaps in part explained by this sense of entitlement described by Solnit; the perception that these women are offering their bodies to men. Consent is the bedrock of healthy sexual relations, but online, it can easily fade into the ether. An anonymous direct message is a relatively risk-free attempt to elicit contact. If no response is received, then the attempts to 'overwhelm the gatekeeper' might begin. The unconsented dick pics, 'Fuck you bitch!' retorts, or bombardment with messages follow. Unreciprocated contact angers the perpetrators, and the abuse continues.

In reality, we behave differently in distinct, policed social spaces, but separate virtual activities can take place in just one window, on one device, in just one room. When pornography is just one tab away from Instagram, it's easy to see how unchecked desire can permeate online spaces. Although Instagram attempts to stop the proliferation of pornographic content, even content deemed non-pornographic can elicit a pleasure response. Athletes and followers can form a symbiotic relationship in a constant feedback loop, in which the athlete posts more of the kind of content that elicits the most likes, and followers seek more pleasure through a process of sensitisation. Is the proliferation of online pornography and the 'pornification' of Instagram a contributing factor in the sexually charged content that athletes receive, as an extension of this cycle of instant gratification?

Everything in moderation

The '70s and '80s didn't shy away from overt sexualisation of women in climbing media: naked women were adorned with climbing rope weaving serpentine around their modesty; nude calendars and gratuitous bikini shots were rife.

'The older generation having had to fight some of those classic battles was unsure of this advertising, whereas younger female climbers who have grown up believing that there are no gender boundaries saw the ad as supporting a positive female gender notion – we climb, we are hot and we are in control,' Mick Ryan wrote in 2005 about a contentious advert at the time. Once again in 2019, the double edged sword of female empowerment vs. objectification is glinting in the media spotlight. The control that female athletes have over their self-portrayal online is, in the eyes of Rebecca Solnit, a victory and a revolt of sorts. '[A woman] struggles with the forces that would tell her story for her, or write her out of the story, the genealogy, the rights of man, the rule of law. The ability to tell your own story, in words or images, is already a victory, already a revolt,' she wrote in Men Explain Things to Me. Social media, then, has the potential to be a platform for empowerment, despite its shadier aspects lurking beneath.

Tori Allen, a champion US climber who was in her teenage prime in the early 2000s and is now aged 30, was a victim of online abuse in its nascent state: forum comments, online articles and emails. Her crime? Being young, female, attractive, enthusiastic and embracing the positive publicity that came her way. Tori paved the way for today's young athletes, working with the media and actively encouraging the commercialisation of climbing. Typically, the private messages she received stemmed from comments on public forums.

'People got so riled up that they had to lash out at me personally,' she tells me. 'The comments were very inappropriate, both publicly and privately. People who never had met me were posting all sorts of lies, claiming they had witnessed things. I apparently had a personal helicopter that took me to competitions and outdoor climbing; I was making $500,000; my parents paid routesetters to give them beta to pass on to me; I packed three suitcases for every trip because I was so spoiled; I threw tantrums at crags; my parents were "pushing" me and I didn't really want to climb...you get the picture.'

Privately, messages occasionally took on a more sinister tone. 'Some were flirting but most were abuse and threats about me "changing climbing" and "making it too commercial/mainstream"; that I was "stealing money" from the "real climbers" and that I was a cheater or didn't deserve what I was getting, and that I was too "girly", too "spoiled", too "immature"...' Facing public and private scrutiny at a young age was difficult. Although most of the comments came from men, Tori asserts: 'Women can be very abusive in messages, often in very different ways than men.'

Women are used to editing their physical appearance in everyday life through make-up and clothing, and this often extends to their virtual persona, too. Some of the female climbers interviewed are cautious about the image that they project online. 'I generally don't post photos of me in skimpy clothing because I usually wear clothes that aren't that skimpy, but if I spent more time on the beach there would be more photos of me wearing less clothing,' Hazel Findlay responds. 'I wouldn't want to post photos of myself in skimpy clothes in order to get more likes because I don't want that kind of following. I do find it sad that some of my better-received Instagram posts are ones that show more flesh or where I look nice,' she adds.

Emma Twyford echoes Hazel's comments. 'I'm fairly careful about what I post. Once in a blue moon I might post a skimpy shot or a bikini shot but I don't want people following me for sex appeal, because it does open you up to all sorts of weirdos - not to knock anyone who does this as it's no excuse for inappropriate messages,' she explains. 'I would rather have fewer followers who are friends, just following my climbing or because they like the integrity of my posts. I try to keep it professional and let very little of my personal life online now,' she adds. Once again, the catch-22 situation that trips women up is discussed. 'Even some of the good guys I know say that by posting suggestive pictures that you are opening yourself up to abuse, but where do you draw the line, because surely that's only a step away from accusing girls dressing suggestively on a night out of 'asking for it' through their clothing if they get raped?' asks Emma.

But what does 'dressing suggestively' mean? Are sports bras and bikinis suggestive? It perhaps hinges on the nature of poses. Sportswear is practical and as climbing clothing for women shifts from the 'shrink it and pink it' styles of baggy trousers and ill-fitting tops to more flattering, feminine cuts, women just happen to both look and feel good in clothes that are better suited to the activity of climbing. This discussion ties in to the athlete/model debate: does an athlete sharing photos in swimwear or underwear deserve to receive more weird stuff than other women who moderate their content more? No, but she should probably - sadly - expect it. Women shouldn't be guilt-tripped or victim blamed for how they choose to dress, rather we should challenge the behaviour of men who send abusive messages or consider every female to be 'asking for it.' Asking for attention is understandable, but not every woman online is asking for abuse and sex on a plate.

Moderation is a key aspect of being female; moderating behaviour in public to avoid a potentially dangerous situation, moderating clothing for fear of judgement. Moderating social media use is an unfortunate modern-age sequitur that many women feel compelled to engage in. Filtering which images to share, which to ditch, turning off direct messaging and blocking accounts. Just another addition to the list of emotional labour that women deal with on a daily basis. Yes, #firstworldproblems indeed, but online harassment is just the thin end of the wedge.

'We tend to treat violence and the abuse of power as though they fit into airtight categories: harassment, intimidation, threat, battery, rape, murder,' Rebecca Solnit writes in Men Explain Things to Me. 'But I realize now that what I was saying is: it's a slippery slope. That's why we need to address that slope, rather than compartmentalizing the varieties of misogyny and dealing with each separately. Doing so has meant fragmenting the picture, seeing the parts, not the whole.'

Female politicians and activists face death threats on Twitter almost daily. As more professional climbers turn their hand to activism and advocacy for environmental, equality and diversity issues, raising voices could attract sharp tongues and pointed comments. Indeed, many athletes - both male and female - have spoken out about the backlash received by followers when expressing a political opinion. '"Stay out of politics!" and "Focus on climbing, sweetie." 'I felt like these comments were jabs at my awareness of the world beyond rock climbing and evidence of the misogyny that exists in our country,' wrote Sasha DiGiulian in an Outside online article. Sometimes, it seems, athletes are denied agency as thinkers and individuals - something which women have endured historically. Thankfully, today's crop of climbing superstars are largely challenging that old 'sports jock' trope, being more than just a pretty face and a toned body with strong fingers.

Nonetheless, sharing an opinion can be more daunting than sharing a photo of yourself, especially when your career is on the line, Hazel Findlay admits. 'I don't post a lot of political content or some opinions I have because I am scared of negative feedback,' she tells me. 'Social media is my job, so negative feedback isn't a question of getting hurt - it could be a question of losing my job, so I generally stay clear of controversial ideas.'

The private and the public

In the days of athlete managers and PR representatives, some professional climbers have access to help with managing their emails and PR requests, but personal social accounts are generally handled by the athletes themselves. The advent of social platforms, therefore, seems to leave climbers more exposed to abuse through private messaging channels than emails. According to the athletes interviewed, the kind of content sent through DMs and the comments made publicly on social media posts vary.

'I receive inappropriate reactions publicly and privately,' a female climber responds. 'The private messages are definitely more inappropriate sexually, but people tend to write abusive comments ('you suck at climbing, you dress like a slut', etc.) publicly. I definitely receive more abuse through DMs than emails.' Caroline Ciavaldini was fortunate to receive coaching in dealing with online interactions. 'We got quite a few media management lessons from our sponsors, and it helped a lot,' she comments. 'Rule no.1 was not to answer nasty messages because it only escalates things.'

The 'Ask me a question' feature on Instagram - a Q&A tool in which followers can submit questions to an account - appears to leave people particularly open to intimate or abusive questions. At the lower end of the creepy spectrum, athletes' responses suggest, is the highly predictable 'Do u have a boyfriend?' I notice one top female climber respond to this with an image of her and her partner. A few taps through questions later, and the same has been asked again. 'Since so many of you asked this..!' Flattery or creepy imposition? I suppose it's down to the individual to decide. A responsibility lies with athletes - as it does with anyone - to carefully control their words, information and images posted online. Once they're in the tangled web, you lose control of them and they can be exploited. Many of the athletes interviewed claim to split their private and public lives by using separate accounts to their athlete pages, but in this climate of constant sharing - in Instagram Stories especially - lines seem to be increasingly blurred.

For younger athletes, the effects of abusive comments and content can be more serious. Parents can and do get involved. 'I had my parents screen my social media for me because I was becoming so overwhelmed by the negativity,' a female athlete recalls. 'They would read through my comments/messages to make sure there wasn't anything that would upset me.' The dangers that the Internet poses to children are well-known, and as more young athletes are making a name for themselves in climbing and making their lives very public, they risk increased exposure to online abuse - something Tori Allen is all too familiar with. 'It was very confusing and hurtful for me and my family when it was "just" forums,' she explains. 'I think people need to be responsible for what they say, even behind a pseudonym. Words matter. There is a real person on the receiving end. If you wouldn't say those things, in that way, to a loved one, a person you respect... then why say it at all?'

I wonder how Tori feels about the advent of social media and its influence today. If she were a young climber in 2019, how might her experience differ to how it was in her youth? 'I'd embrace it but I'd be very intentional about it with an audience in mind, targeting tweens and focusing on healthy things. I'd feel a responsibility to give back and social media would be a great platform.' While Tori was unique in her forward-thinking approach to publicity in the early 2000s, now her media-savvy legacy is more prevalent and - broadly speaking - accepted by the climbing community. Consequently, today people perceive her in a different light. 'Interestingly, the tide really turned,' she explains. 'Newer climbers started reaching out and thanking me for paving the way for the opportunities they had and some older climbers apologised. People sometimes find me on social media now and want to rehash things, but overall it has been positive.'

Today, in a sea of hashtags and sponsored posts, Tori's media contributions would likely be a drop in the ocean. Being an exception to the rule made her an easy target to be singled out for abuse. Unfortunately, though, as more people participate in climbing - and more women especially - at all levels, from beginners to pros, the online harassment has become widespread.

Climbers Against D*ck Pics

Climbers Against D*ck Pics (@chossydms - 'chossy'/rubbish direct messages) was started by a group of female climbers from the US. 'The idea came from a group chat where we would share what we got sent with each other,' one of its creators explains. Generally, the climbing community has responded well to the page, which now has over 5,000 followers. 'It has raised awareness of the sexual harassment women face and has created constructive conversations around the subject. People are sending their DM examples daily,' they commented.

Regarding the point and purpose of the page, the creator underlined their hope that it can play an important role in education and raising awareness, rather than providing a source of entertainment. 'We hope that people become more aware of this type of sexual harassment and create an empowering environment where women/men know it is not OK to receive these messages and that they are not alone.' Women comment on the posts with knowing eye-roll emoticons and witty retorts, while some men appear genuinely shocked by what they see. 'At the risk of sounding stupid, is this a real thing?' one male asks. 'Do dudes really send unsolicited pictures of their junk to strangers?' A woman responds with the sad truth, and he comments sympathetically: 'That's so messed up! I'm sorry ladies have to deal with garbage like that.' #NotAllMen indeed, but educating both men and women about the reality of what is happening online and outside the virtual world is a huge step in stamping out sexism and sexual harassment.

'Violence is an abuse of power that hinders a person's ability to be physically and emotionally safe in the world,' Fairbairn writes. 'This world includes the Internet.' In acknowledging the online experiences of these athletes, perhaps we can help to affect change on a more global scale, one click at a time. Chossy DMs is playing an important role in this regard. As one of its followers responded to the aforementioned shocked male, 'But it doesn't just stop at unsolicited pictures. There's the unwanted touching from strangers, and the unwanted comments and remarks.' But it doesn't even stop there. Then there's rape, and possibly murder. To paraphrase the words of Rebecca Solnit, social media abuse doesn't seem to have a race, a class, a religion, or a nationality, but it does appear to have a gender. The Good Guys are implicated in the abuse if they perpetuate the idea that men can't help this behaviour; a myth as unfounded as the bra-burning feminists of the '70s.

Emma Twyford summed up her feelings on social media harassment powerfully:

'We are real people, normal except for the fact that we climb hard. We all have feelings and are no different to anyone else. We should be able to post pictures that show who we are and not have to think carefully about what the response may be, but unfortunately we do,' she writes. 'We also have family, partners and friends - whilst we may be used to brushing off these comments, they may not be. To those posting inappropriate comments I would like to say: imagine that some random stranger posted abuse to your daughter or son's social media, how would you feel?'

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

- ARTICLE: Alexandr Zakolodniy - A Climbing Hero of Ukraine 26 Apr, 2023

Comments

I think that is probably far and away the best article I have read on Ukc. Thanks Natalie Berry.

It's very encouraging to see that subtle online forms of aggressive sexism and such like are being taken seriously and hopefully stamped out.

Many thanks, read this on my lunchtime at work. It is a difficult and challenging read but at the same time very important. Great article.

Absolutely superb. Thanks Natalie.

Well this lifts a lid on a horrible aspect of climbing. It's disgusting. Name and shame the foul f**kers who do this kind of thing - if we can.

Great article Natalie. Depressing to be reminded of the truth that so many men are horrible - but also important to be reminded. Sigh.

A friend of mine is married to an astronaut (yes, seriously) and her official Instagram profile is equipped with a feature that detects abusive content - anything with words like "bitch", "slut" etc. etc. - and filters it so that the abusive poster thinks it has been uploaded (they see it on the comment thread) but nobody else sees it. Quite clever, but as far as I can tell instagram only have this enabled for "verified" profiles, and perhaps only upon special request. A shame, as it could mitigate at least some of the crap (not sure if it also applied to DMs).