Pt. 3: Improving Spatial & Temporal Aspects

Climbing coach and movement expert Udo Neumann is producing a UKC series on understanding and practising adaptable skills that you can apply to the dynamic and complex movements becoming popular in indoor bouldering, from IFSC World Cup finals to your local wall. In Part 3/3 Udo looks into some spatial and temporal aspects of modern bouldering and how to improve them.

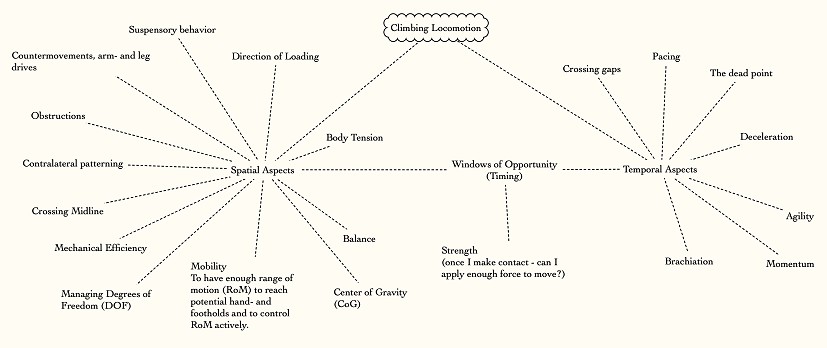

Climbing is a physical activity performed against gravity. It is the combination of body movements created with kinematic and kinetic parameters. The fundamental mechanical interaction between the climber's centre of gravity and the supporting environment has spatial and temporal aspects to it. When we climb well, movements of several limbs or body parts are combined in a manner that is well timed, smooth, and efficient.

Modern bouldering involves sophisticated movements with complex biomechanics and the constant management of forces such as gravity, elastic recoil, torque and momentum.

Performance is tied to diverse elements such as muscle fibres, neural control, elastic properties, distribution of loads over many joints and much more. No single element works on its own and depending on the context even the smallest factors may have a major impact.

Most climbers are obsessed with their ability to produce force. While force production is an important first step and rate of force development is a distinguishing factor for bouldering performance, a lot more needs to be considered!

Modern bouldering is about producing - but also about absorbing, storing, and redirecting and transferring force.

How well force can be used is based entirely on how well the energy gets transferred. The determining factor here isn't whose muscles fire faster or stronger, it is if muscles put joints in the optimal position at the right time to utilise gravity and momentum!

Even minor errors during the time when muscles are activated and deactivated can cause major deteriorations in performance because of a leak in the energy transfer.

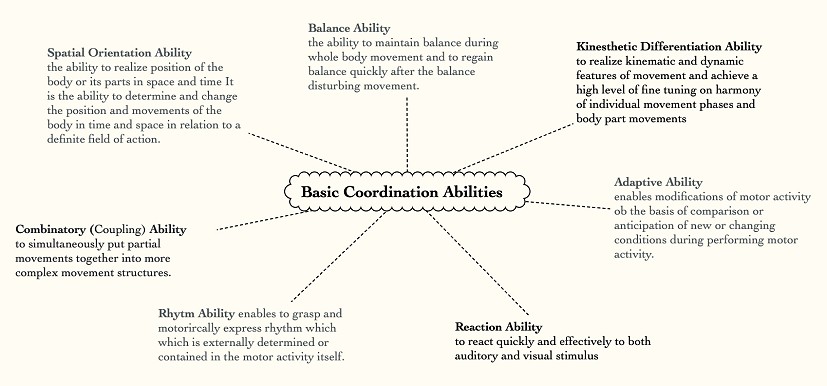

Modern bouldering means to quickly and purposefully perform difficult spatio-temporal movement structures. The complex of coordination abilities consists of a group of basic coordination abilities.

Coordination of multi-limb movement involving both contraction and relaxation is fascinatingly complicated and is "not just a simple addition of activities of muscle in different limbs and the other's activity." Recent studies, for example, demonstrated that muscle relaxation in one limb can suppress muscle activity in the other ipsilateral (on the same side) limb (Kato et al., 2014, 2015, 2016). As an example, muscle relaxation of the foot dorsiflexor (as when toe-hooking) can create a state in the hand muscles such that a required contraction is difficult.

Mobility

How well climbers get into the optimal position is dependent on their mobility. Unlike any other quality, climbers can't have enough mobility. Greater mobility gets them in touch with the contact points and more options for movement in the gravitational field with less effort. Whenever you see an interesting pose in a climbing comp, try to get into this pose, using the ground for support if necessary. You'll find that some of the poses are well outside the reach of ordinary climbers.

Modern bouldering asks for extraordinary mobility in every joint, in every angle, under any load. The required level of mobility for international climbing comps is a lot higher than ten years ago, partly because of the dominance of the Asian climbers. Their feet and ankles, for example, are often more useful tools than the ones of their competitors.

The Centre of Gravity (COG)

CoG is an imaginary point around which body weight is evenly distributed. The CoG is the focal point of gravity's pull on the body. The CoG lies approximately about 10 cm lower than the navel, near the top of the hip bones.

The direction of the force of gravity through the body is downward, towards the centre of the earth and through the COG. This line of gravity is important to understand and visualise when determining your ability to successfully maintain balance. When the line of gravity falls outside the Base of Support (BOS), then a reaction is needed in order to stay balanced.

The precise location of the CoG changes constantly with every new position of the body and limbs and can even be away from the body. Additionally, the centre of gravity can change because the segments of the body can move their masses with joint rotations, as I describe further below when we talk about momentum. This concept is critical to understanding balance and stability and how gravity affects climbing techniques.

Hips don't lie

Control your hip and you control your body. Unfortunately, it is difficult to create a sense of balance in this joint. Even climbers that most likely don't lack basic mobility and who outwardly appear flexible, experience a sense of tightness or restriction in the hips.

Without a sense of balance, there is no confidence in hip coordination. Without confidence, there is no mobility and control.

Educate yourself concerning the difference between movement at the hip and movement at the pelvis. This effects overall coordination between the two areas. Better interaction between hip and pelvis increases balance, coordination, and mobility at the hip joint.

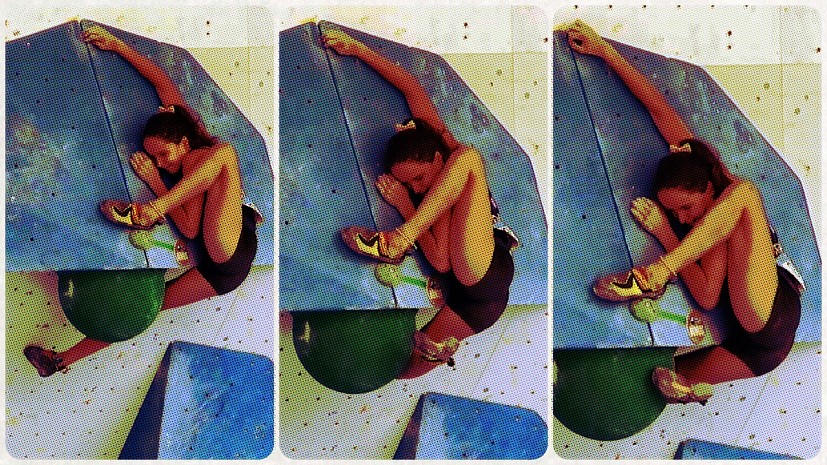

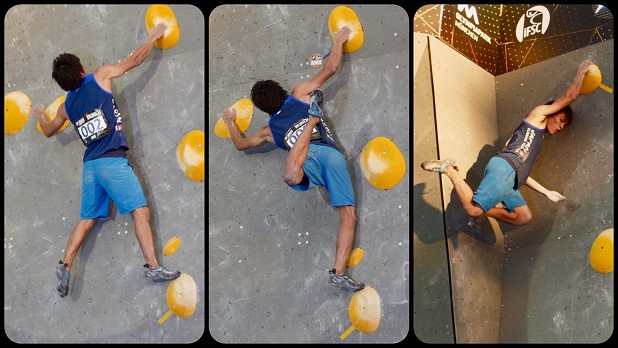

How moves are initiated distinguishes traditional climbing and modern bouldering. Traditional climbers engage with the contact points through the limbs before the trunk in a distal to proximal fashion. Compare this pattern with how Tomoa Narasaki initiates movement with his centre of gravity. This proximal to distal pattern makes just about any movement considerably easier.

Tomoa's mastery of hip movement in all planes and around all axises allows him to control whatever kind of movement he wants to create. From a training session in 2015, when nobody knew that the best of modern bouldering was yet to come.

When analysing climbing movements, you want to see if the CoG moves in the climbers' favour or not. Get a view from different angles, you'll be surprised how different movements look depending on perspective!

To an extent, climbing is about throwing your hips into the right position and letting good things happen! Often your job is done when you have managed to bring your CoG as close to the target hold as possible. But if you miss, that often results in a failed attempt, regardless of beta used and what you do with your limbs afterwards.

By mastering hip control in all planes and around all axes, climbers can control whatever kind of movement they want to create. You can be as static or dynamic as the hip allows. Consider that the hip moves around and plays in 3-dimensional space. Front to Back, Side to Side, Twist and Turn and everywhere in between.

If you combine the impulse and the timing too, the sensation feels like riding a magic carpet!

If you raise the Center of Gravity for as long as required to do the necessary hand- and foot moves, this plateau of the Center of Gravity (CoG) is your magic carpet that, while you are riding it, allows you to do whatever you want.

No-hand exercises are very educational for hip control since without hands you are much less able to compensate for a faulty centre of gravity. You also learn to focus your eyes on external targets and use your arms and other body parts to counterbalance.

Challenge yourself daily by trying to achieve balance in different poses and even with eyes closed. You want your movement from the hip to be fluid and confident.

Contralateral control and crossing midline

The arrangement whereby most of the human motor and sensory fibres cross the midline in order to provide control for contralateral portions of the body is called contralateral control. Most people favour one hand or foot for some tasks and the other hand for other tasks - this is called cross dominance.

Bilateral integration is the communication between the right and left cerebral hemispheres, which allows the two sides of the body to move together in coordination with one another.

Crossing the midline is our ability to move one side of our body across the middle of our body to the other side. This is not trivial, and every human struggles from time to time with it.

Climbers experiencing a hesitation or inability to cross the midline with the hand or foot may have difficulties with shifting weight, complex movement sequences and following through across the body, for example when absorbing a swing. The lack of proper follow- through and weight shift illustrate midline crossing problems.

Competence in crossing the midline dramatically increases a climber's options in complex movement sequences for additional reach and following through across the body.

Agility

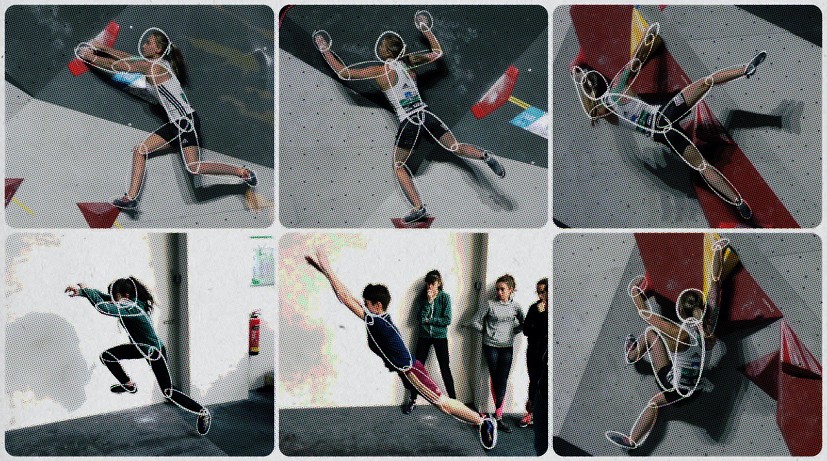

This is the ability to take different positions. Agility can thus refer to both mental and physical stirs and impulses. In climbing, agility is the ability to maintain and control ideal body position while quickly changing direction through a series of movements.

Agility is a neuromuscular skill consisting of movement and reaction aspects. Muscle strength also plays a crucial role in agility, especially in adolescent athletes.

Agility has two major components, cognition and change of direction speed. The cognitive aspects include perception and decision making, and change of direction speed is affected by both technical and physical factors.

Perceptual and decision-making processes associated with agility performance are trainable and decide bouldering contests.

Momentum

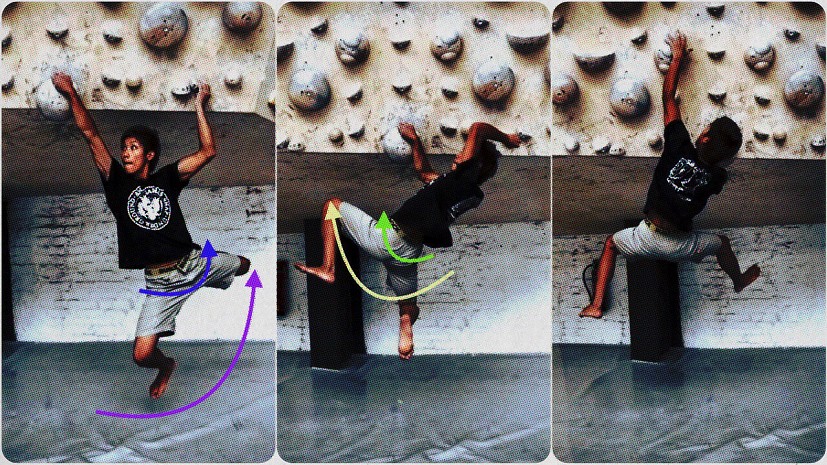

During dynamic movements, the Center of Gravity (CoG) can be outside the body. When the CoG is in front of us, there is no pulling back and we need to be proactive and committed. It is often at this point when many climbers struggle with momentum in climbing.

Remember the concept of the challenge point for practising momentum and start really easy, for example with jumps and step sequences on the ground. Gradually expose yourself to more complexity and constraints. Once you become fairly confident in using momentum on the ground, it is time to involve your upper body and use momentum in different planes and contact points.

Explore how different body segments have distinct centres of gravity and can be used as energy vessels to transfer angular momentum to different body parts and different axes and planes of movement and/or rotation.

The best climbers can initiate angular momentum of some body part from a state of having no whole body angular momentum if this angular momentum is counterbalanced by some other body part in the opposite direction.

Often we observe conservation of angular momentum, the so-called whip effect.

Our joints are arranged in opposing directions of motion, allowing the body to "fold" and "unfold." This concept of opposing joint torque is the principle of posterior chain tensegrity that allows for big-time utilisation of elastic energy in climbing.

Counter-Movements

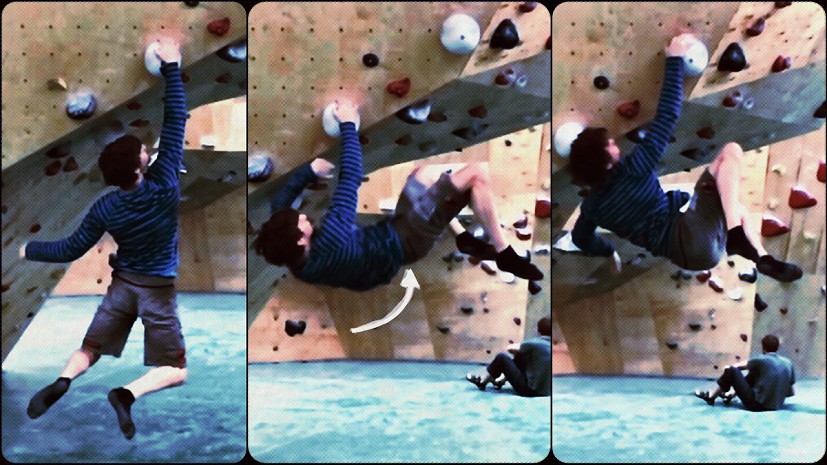

Most forms of jumping are initiated with a downward movement of the body referred to as a counter-movement. This action serves to increase the distance considerably. This increased performance is attributed to a greater range of movement during the propulsive phase and the use of the stretch-shorten cycle.

The stretch-shorten cycle describes the sequence of movement whereby an active muscle is first stretched and then shortened. The stretching phase results in a more forceful shortening of the muscle than if there had been no pre-stretch.

Collision Fraction

The redirection of the Center of Gravity during locomotion when a climber grabs a handhold follows the same principles that govern redirection of colliding objects. The angle between the Center of Gravity force and velocity vectors - as their orientations change throughout the move - determines the collision angle, which often decides if we can hold a hold or not.

Better climbers distinguish themselves with shorter contact time and better control of peak force through more sophisticated collision fraction.

Energy losses due to inelastic collisions of the climber with the holds are avoided, either because the collisions occur at zero velocity, at the so-called deadpoint, or by a smooth matching of circular and parabolic trajectories at the point of contact in every joint of the body. These sophisticated transition types through all joints for collision reduction form a continuum, rather than clearly distinct types.

The more collision reduction there is, the better the motion is adjusted. The best climbers show the smoothest motions!

Terminology

In our quest for better understanding of movement and locomotion, it would certainly help to develop a commonly used terminology.

The first term I would like to discuss is 'Campusing.'

In bouldering, it is sometimes easier to let our feet swing through the air instead of trying to use them on the wall. This liberates the choice of our body's position in three-dimensional space.

'Campusing' seems to be the established term in English-speaking sport climbing and bouldering communities. The term stems from the Campus board, a two-dimensional training device.

Training on the Campus board is intended to build finger, arm and shoulder strength. It consists of bending your arms with hands in a pronated position and a static phase while reaching the next rung with the other hand.

Bear in mind that this is a training exercise, not the most efficient movement. If we initiate the motion with our centre of gravity we can move faster and more efficiently with just our hands.

Hangeln is the German term for this locomotion. Hangeln is understood by everybody in the German speaking world, regardless of age and background. Hangeln is what monkeys do in the trees.

Unfortunately, there is no commonly understood term like this in English. This is reflected in the English translation 'brachiation' - a term used in zoology but not in climbing circles.

Hangeln is a truly three-dimensional movement involving our whole anatomy. Every part of our body is spiralling in a particular fashion and sequence. The body is a true gestalt entity – the total is more than the sum of its parts.

We're only just at the beginning of realising what brachiation or hangeln (or whatever we end up calling it in English) can do for our climbing - start by not calling it 'campusing' anymore, will ya?

Udo Neumann is the author of Performance Rock Climbing, Der XI. Grad and Lizenz zum Klettern. Recent video publications include 'Climbing Technique of the 21st Century' and the 'Ideas to improve your Climbing' series. From 2009 -2017 he was the German Bouldering Team coach with World- and European Champions to his credit. Today, he advises federations and teams and coaches athletes and coaches. Check out his YouTube channel.