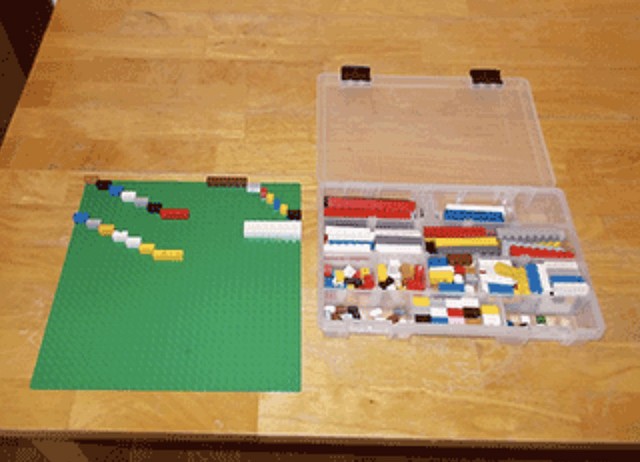

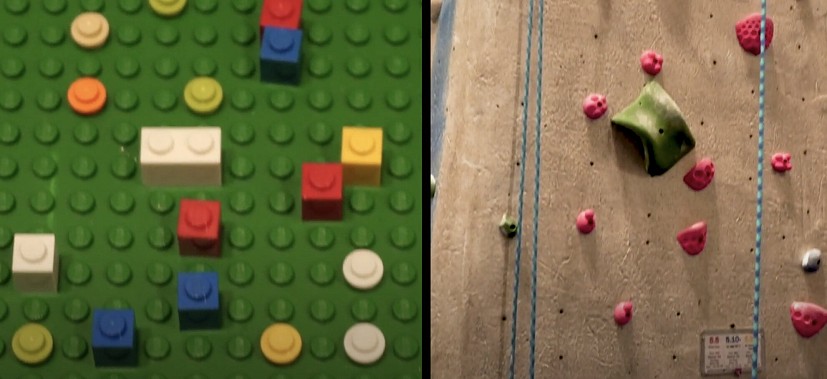

As Matthew Shifrin ties-in at his local climbing wall in Boston, his belayer breaks open the LEGO. A baseplate, some bricks and tiles are clicked together in a mishmash of colours. Matthew runs his fingers over the studs and tiles. 1x1 cylinder...pinch. 1x2...jug. Flat, smooth 1x1 wedge...foothold. This tactile routemap allows him to build a mental picture of the route - almost like a climbing-specific Braille system - and imagine the shape and sequence of the hand and footholds. As Matthew steps off the ground and onto the wall, his belayer switches roles to become a 'caller', shouting out directions to alert Matthew of the relative positions of holds. "Right foot, left knee"; "Left, 1, 2."

Matthew is blind since birth. LEGO has played an integral part in helping him to make sense of the world around him ever since a chance encounter with the construction toy at the age of five when a family friend, Lilya, found a jumble of discarded LEGO in a box on the street. 'It was just a bunch of bricks and pieces, but I was hooked,' Matthew says. 'Unfortunately I couldn't follow LEGO's instructions to build specific models, since they're pictures, and can't be translated for the blind. Or so I thought.'

As a gift for Matthew's thirteenth birthday, Lilya patiently set to work creating a binder of hand-punched instructions by Braille typewriter for an intricate Middle Eastern LEGO palace that she had bought him, ascribing names to every piece and outlining every step of the construction process. 'For example: Put a flat, smooth 2x1 vertically on the front left corner of a 32x32. Put a flat, smooth 6x1 horizontally to the right at the front. Repeat,' Matthew explains. 'It was incredible to finally be able to do what so many kids do all the time.'

The more LEGO sets Lilya adapted, the more Matthew wanted to share this experience with other blind children. The pair launched a website - legofortheblind.com - where they posted text-based instructions for whatever sets they could get their hands on. 'We were bombarded with e-mails from blind kids and their parents and teachers, asking us to adapt their favourite sets,' Matthew remembers. 'There were so many requests, that we just couldn't do it all. We were just two people in a living room doing this in our spare time. We wanted to get in touch with LEGO and ask them whether they could create their own instructions for the blind, but we just didn't know who to talk to.'

Less than a year after the site launch, Lilya died of cancer. Matthew and the LEGO project were in a state of limbo, and he needed an instruction-writer to continue what Lilya had so benevolently started. Matthew was in luck: another fortuitous moment during a discussion led to contact with a friend-of-a-friend who had moved to Denmark to work for LEGO, who put him in touch with Olav Gjerlufsen, the head of LEGO's Creative Play Lab. 'Olav created a technique that used AI to take LEGO's graphical instructions and translate them into text-based directions that are easy to understand and follow,' Matthew explains. 'LEGO has made 30 sets accessible for the blind (available on legoaudioinstructions.com), and will be adding more in the years to come, so that someday soon, every set will come with downloadable text-based instructions for blind builders.'

Now aged 22, Matthew has been described online and in the press as 'a blind entrepreneur', having innovated and inspired through his work with LEGO and in the music world and beyond. He's a professional composer and musician, and credits his enhanced auditory sense and grasp of pitch to his blindness. 'It's forced me to focus much more of my mental energy on my hearing, so as a result, I've trained myself to listen more intently and be able to follow multiple conversations simultaneously, for example,' he says. Matthew also has Perfect Pitch, which means he can identify any note that someone plays. 'It's a skill many, but not all, blind people have, and I think that blind people are predisposed to musicality because they focus so much of their energy on their hearing,' he explains.

Being so reliant on each of their functioning senses, touch and tactile awareness of surroundings are equally vital for blind people. 'They're crucial for me in order to understand the world around me,' Matthew says. But there's a drawback. 'Touch is sequential, meaning that unlike sight, in which the brain stitches together visual information to show you a complete image, you can only touch parts of an object, and your brain must then try and fill in the gaps, to figure out what that object is,' he explains. 'I can't climb the Sydney Opera house, or Big Ben, to figure out how they're shaped, so LEGO acts as a miniature replacement, allowing me to touch and 'see' the untouchable.'

That doesn't mean that Matthew can't reach great heights otherwise, though. Matthew dabbled in indoor climbing as a child and enjoyed the freedom of grasping for holds and progressing up the wall. 'I'm generally very anxious since there's so much uncertainty when you're navigating the world as a blind person,' he admits, 'but when I climbed as a kid it was just me and the wall.' Last year, a friend who coaches a team of disabled climbers invited Matthew to tie-in once again. Without his youthful exuberance and energy, Matthew's movements needed to be more considered and his mentality was less relaxed and more focused. 'Now I was a pawn on a game-board trying to get from point A to point B as quickly and efficiently as possible,' he explains, 'with the added hurdle of not really knowing how to get there, since I'm blind!'

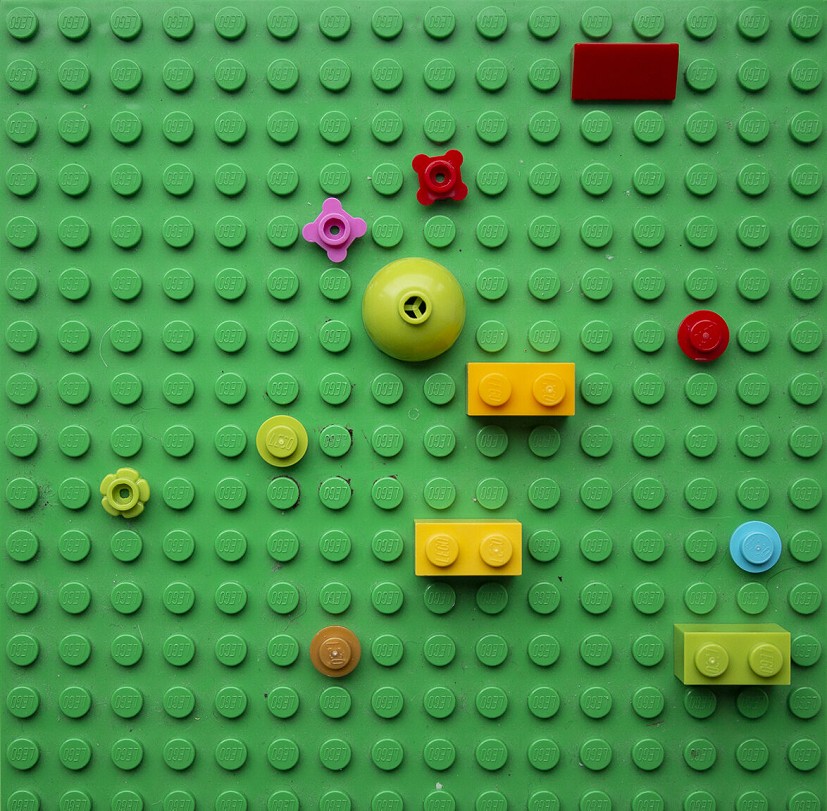

With the help of a friend once again, Matthew developed a tactile LEGO route map tool of sorts for blind climbers. A sighted person builds a replica of a climbing route so that the blind climber can form a mental picture of the route from the LEGO piece 'holds' and the relative positions of each by touch - like a form of Braille. The system was inspired by one that Matthew's music teacher had invented using LEGO bricks to help blind people notate music. Different bricks represent different durations of notes, 2x1: 8th note, 4x1: quarter note, and so on. Matthew took that idea and applied it to climbing, making different pieces symbolise different hold types. 'Pinches are 1x1s, jugs are 1x2s, ledges are 1x3s, etc.,' he explains. 'The smaller scale of LEGO allows blind climbers to calculate the distance between holds more easily, and apply that knowledge to their climbing.'

To complement the LEGO map, Matthew also uses a sight guide and headset when he climbs - a common support system used widely by recreational blind climbers and in paraclimbing competitions. 'The sighted guide (known as the 'caller') gives information on where hands and feet should be placed, and how far away holds are from you,' Matthew says. 'For example: "Left foot, Left Knee," means that there's a left foot-hold at your left knee, and "Right, 1, 2," means that there's a right hand-hold at 1 O'Clock, 2 feet above you.' While the map is invaluable for understanding basic sequences and body positions on a route, Matthew's caller is able to give him tips on how to approach the climb on a more technical level. He says that their communication has greatly improved since starting to use the LEGO system. 'As a blind person, you have to trust people a lot in your daily life, and you're never quite sure of their intentions,' he explains. 'I'm so glad that I can trust my caller completely in what is quite a scary and potentially risky sport.'

The LEGO map has its limitations, however. 'Though I know what a jug or crimp feel like, there are so many slight variations of hold shapes, that I try to just go with the flow,' Matthew says. 'The map is great as an outline of what kind of holds you can expect, but it can't tell you everything - such as hold size - so you trust the map, but you also need the flexibility to think in mid-air, figuring out how to approach different holds as you grab them.'

Without a sight guide or LEGO map, 'non-sighting' a route is considerably harder for Matthew. 'Doing a route mapless and without a caller is very difficult; since you don't know your destination, you're just desperately grabbing onto anything trying to stay as close to the wall as possible,' he explains. 'The best blind climbers exhibit incredible control, climbing very slowly so that they can plan every movement of their body. When you climb a route sightless, there's nothing you can plan for, since you have no idea of what lies ahead and how to approach it.'

Although Matthew hasn't tried the map outdoors yet, he thinks it could work. 'I've used the system with blind outdoor climbers, and they've said it would be useful to them,' he says. He also hopes that it will be employed in paraclimbing competitions across the globe in future. Matthew's unique approach to climbing frequently attracts attention at the wall. 'People are very curious and excited about the system when they see me using it at the gym,' he says. 'I think the fact that it's LEGO really helps!'

Aside from the physical and social benefits of climbing, the sport can help blind people in other ways. 'It's a great activity for helping blind people train their proprioception, or spatial awareness, since it requires precise and accurate movement of all of your limbs, and a thorough grasp of your body in relation to the wall and the holds,' Matthew comments.

When he's not climbing, Matthew is devoted to helping other blind people, while educating the sighted population about the challenges faced by - and the capabilities of - those with visual impairments. He has presented multiple TED Talks, including one on the importance of augmenting the power of language. 'Language is an evolving flexible medium, and it can be shaped and moulded to solve almost any problem you come across,' he explains. 'I think it's crucial to always think outside the box when problem-solving and to think unconventionally. If Lilya hadn't stretched the English language to its limits when she created the text-based LEGO instructions, I wouldn't be climbing today.'

As an ongoing passion project, Matthew is interested in the use of binaural sound and virtual-reality (VR) headsets to improve sensory experiences for blind people. He recently began a project with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab, which won the MIT $15K Creative Arts Competition, creating VR comics for the blind using 3D sound and head-mounted spinning gyroscopes to simulate motions such as flying. 'I hope that immersive entertainment experiences will become more accessible to blind people in the future,' he says. If developers incorporate accessibility features into their process from the get-go, those features will help everyone, not just the disabled community, Matthew explains. 'Closed Captioning, for example, was first invented to help deaf people enjoy television, but now hearing people use it all the time when they want to watch TV without disrupting others,' he says.

Step by step, piece by piece, Matthew is building a career in both music and innovation for the blind. He's currently finishing his Bachelor's Degree in Contemporary Improvisation at the New England Conservatory in Boston, while applying to Master Programs. Climbing is still on the cards for the forseeable. 'I'll definitely keep climbing and I hope to compete soon,' he says.

The most important question...what's his favourite LEGO set?

'The Tower Bridge is awesome!' he responds.

Watch a BBC and Yahoo profile of Matt, and his Lego TED Talk below.

- SKILLS: Top Tips for Learning to Sport Climb Outdoors 22 Apr

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

Comments

Wow! :-)

What an interesting, accomplished guy and what a smart use of Lego.

That is really impressive and inspiring.

The blind are showing us how it's done recently with this and Jesse Dufton's output. I had a funny experience at the wall a couple of years ago - silently judging bloke for all the tickmarks on a route. He gently calls down "is this a purple, I can't see?". That's me back in my box :)

This is awesome, great article! , I bet loads of climbers would love to be a "caller" (some people cant helpthemselves even for the sighted), it would be easy to find volunteers if a blind school wanted to take their kids climbing.