Culm Dancing - Beginnings

The beginnings of climbing on the Culm Coast and Baggy Point in North Cornwall and North Devon seem to follow a pattern; discovery, enthusiastic exploration and then, once the idea of it as a new climbing area has been thoroughly conceived, complete inaction; for decades. This in contrast to other British climbing grounds, made it possible for beginnings to last a full seventy years!

At the very start of the beginning, the great adventurer Tom Longstaff had, from the age of twelve, during visits to his cousins, been at deep play on the North Devon coast, traversing and exploring the rocks above the sea. This exploration culminated in the climbing of Baggy Point's Scrattling Crack in 1898 which as a 40 metre v.diff, should be correctly cited as the South West's first sea-cliff climb.

'The crack is about 130 feet long, but not difficult since it is not really as vertical as it looks and a foot or knee can always be squeezed in.'

Longstaff was soon away from the coast, to larger objectives, travelling to Tibet in 1905, and in 1907 making the first ascent of Trisul, which was the first 7000 metre peak to be climbed. Longstaff's early probings went virtually unknown until the publication of 'This is my Voyage' in 1950.

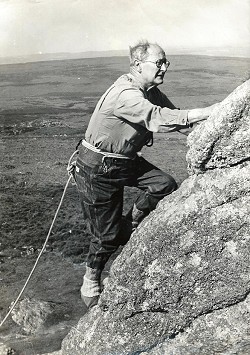

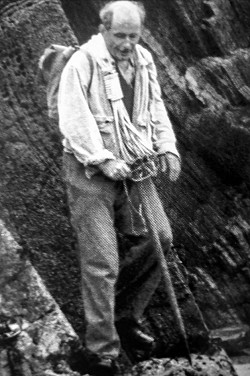

The whole coast now lay dormant for decades. Rennie Bere the famous naturalist and mountaineer of Ruwenzori fame made a few solo outings including the North Ridge at Compass Point whilst holidaying in Bude during breaks in his work in the British Colonial Service in Uganda but left no notes of his activities. He retired to Bude in 1960 and still scrambled on the cliffs into his dotage.

The mis-identification as an airfield and subsequent bombing of the Clifton College Preparatory School cricket ground by the Luftwaffe in 1941 sparked the start of the middle of the beginning for the Culm Coast. It was decided that the whole of the upper school be evacuated to Bude and for the school to be set up in the Edgecombe Hotel. Hockey on the beach, learning to swim in the sea pool and watching American troops taking part in landing manoeuvres were the order of the day.

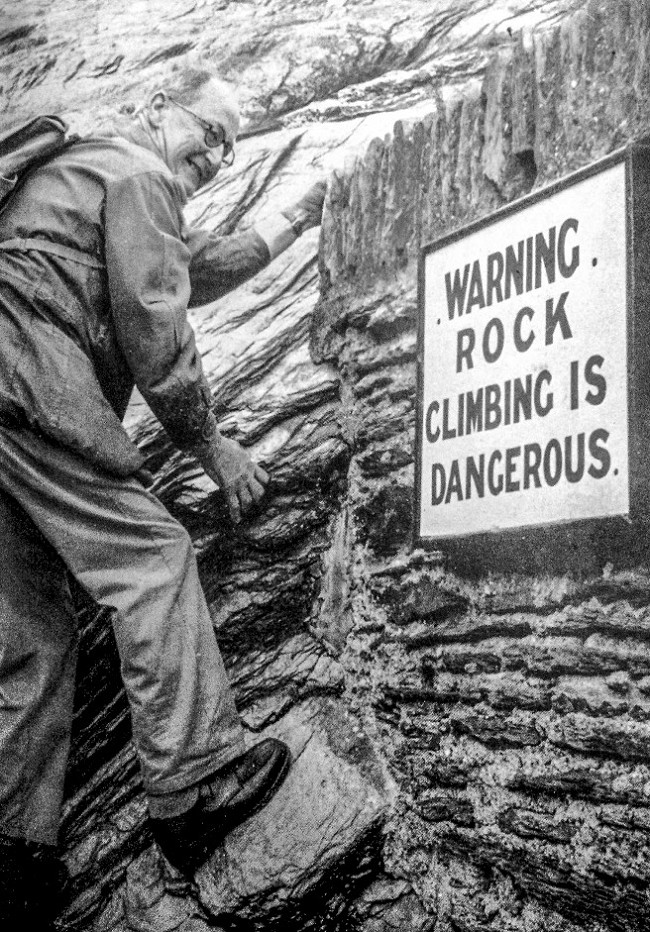

For one housemaster and member of the Fell and Rock Climbing Club, Ernest Hazelton, the hand of climbing opportunity beckoned. Hazelton climbed and recorded a number of routes on the coast. In his article which appeared in the 1945 FRCC journal, he shows his deep understanding of the geological vagaries of the Culm.

There is little at Bude to gladden the heart of the rock climber, indeed it would not be easy for any ordinary member of the Club to find words sufficiently abusive. The cliffs are friable, treacherous and end at their summits in yards of bare soil. Nevertheless, difficult as it has been to sing the songs of Zion in a strange land, oases of happiness have been discovered.

The coast runs due north and south and is notable for its crumbling cliffs and its opportunities for surfing. Its quantities of sand would overpower the most unemotional of Walruses and Carpenters. The rock-strata chiefly stand up vertically. The shale rots away between slightly firmer layers.'

Despite his obvious disdain for the rock quality, Hazelton did climb, recording a number of routes at Compass Point including Westerlation, and on pinnacles at Northcott Mouth and Sandy Mouth. These routes have been duly located during work on the new guide and after more than seventy five years, he will now be properly credited for his deeds. Hazelton obviously enjoyed the wild and isolated feel of the coast.

'Walking north along the sand as the sun lights the cliffs before one, their colours are superb. On clear evenings as the sun dips his final green ' flash ' lasts into a momentary glow. You will certainly be alone and may serenely contemplate the sand and waves beneath you or Lundy Island to your right and Tintagel Head to your left. America will be further away in front of you.'

The end of the war and the retreat of Clifton College back to Bristol marked the end of yet another false start for Culm climbing and another period of inactivity blanketed the coast. This was to remain so until a remarkable pair began to look at the potential away from the established climbing areas in West Cornwall and Dartmoor. In 1956, Admiral Keith Macleod Lawder and Edward Pyatt, following a tip-off in Haskett-Smith's writing of 1894, began to survey the Cornish coast in the hope of finding another area which offered the climbing possibilities of West Penwith. This period marks the end of the beginning.

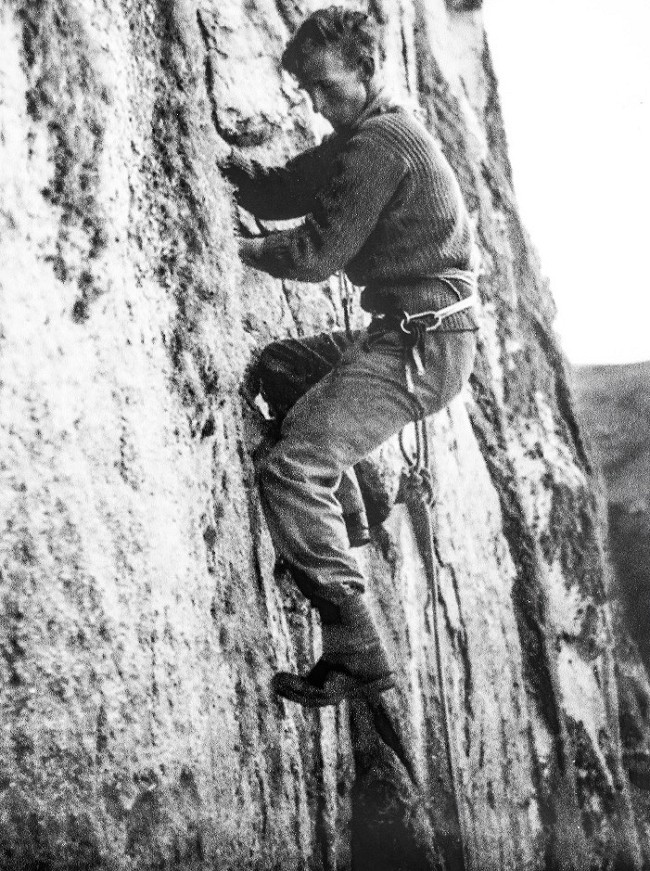

Lawder had exploration and adventure in his bones, having gone to sea for the first time at the age of 19, fought in the battle of Jutland and been in charge of the Gibraltar Dockyard during World War Two. His final naval posting was after the war as Rear Admiral in charge of Devonport Dockyard in Plymouth. Having caught the climbing bug following a clandestine ascent of the Rock of Gibraltar, in 1947 he became a member of the Royal Navy Ski and Mountaineering Club and began his climbing career. He quickly began to develop new climbs on Dartmoor and wrote the 1957 guide to the area. He was also the custodian of Bosigran Count House during the period of frenetic activity during the 50s. This quickly connected him to all of the leading climbers operating in the region and his house at Brook Cottage was visited by many members of the CC who collected the hut keys en-route to West Cornwall.

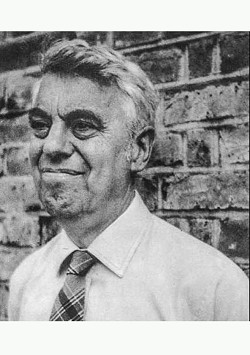

Pyatt, who co-authored the 1950 Climbers' Club guide to Cornwall as well as a number of guides to Southern Sandstone worked in research at the National Physical Laboratory. Pyatt was deeply organised and meticulous; just the man for the detailed recording of climbing possibilities on the north coast.

Over a period of about four years, the pair walked hundreds of miles of coast, mapping features, investigating crags and recording possibilities as well as making some new climbs of their own on the Culm Coast. They eventually published their findings in the 1960 Climbers' Club Journal in an article entitled 'A New Cliff Climbing Area In The West Country'.

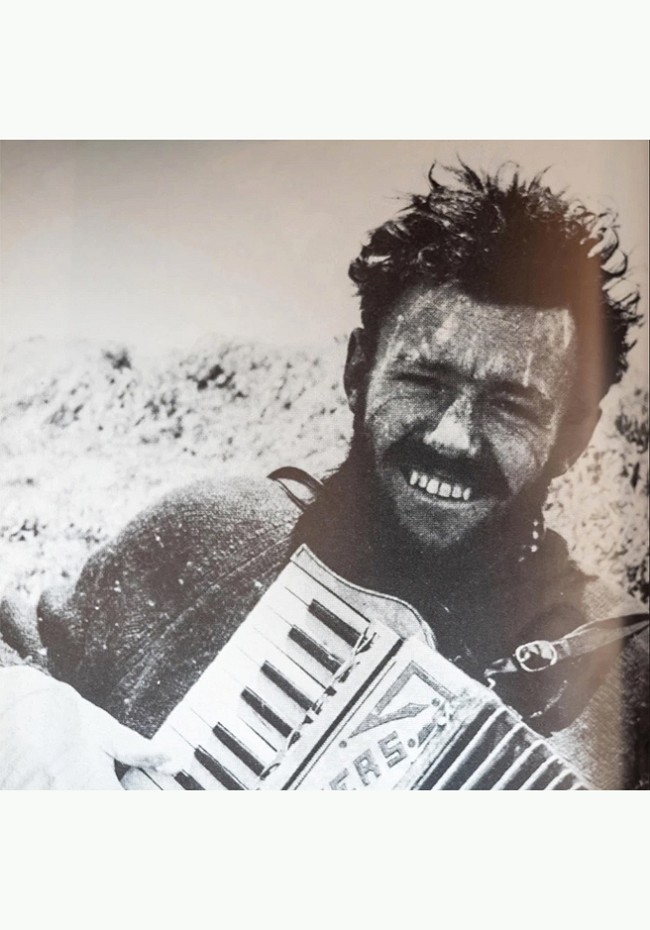

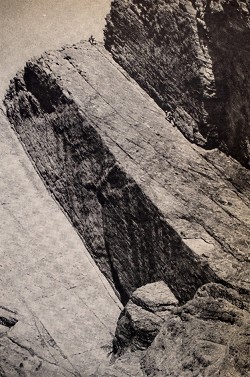

The feature which fired Lawder's enthusiasm most was the huge slab at Cornakey Cliff near Morwenstow. In the summer of 1959, Lawder made a call to his great friend, Major Mike Banks who was in charge of the Cliff Assault Wing and asked for two climbers for an attempt on his unclimbed route. Banks said he could think of a perfect pair and sent Corporal John 'Zeke' Deacon and Surgeon Lieutenant Tom Patey up to the Culm Coast to meet him. Zeke remembers the day clearly as he and Patey, with the Admiral between them took turns to lead their way up both Wrecker's and Smuggler's Slabs the same day, "We climbed a line to the right of where it goes now and had never climbed anything so loose and vegetated. We used pegs only for stances and there were no running belays."

Wrecker's is truly a route of tremendous character, a terrible rock climb in the conventional sense but a superb experience which has deservedly become an enduring classic. In a letter to the Admiral after repeating Wrecker's Slab solo, Patey apologised for having inadvertently removed a number of the holds used on the first ascent.

He continued to visit the Culm, adding climbs in the Hartland area and on the huge cliffs of Higher Sharpnose Point before returning to the Highlands and a life of continued adventure on completion of his military service. Zeke also left the military at around this time and moved away from the West Country for a time.

Apart from the solitary but serious effort of Duncan Finlayson and Rhiannon Lewis on the short lived (due to collapse) Mainsail at Brownspear Point, the Culm once again fell silent and the emphasis moved. The sixties in the South West saw a great development of climbing, based initially on the granite of West Penwith and Dartmoor followed by an explosion of activity at Chudleigh and latterly in Torbay. With the spotlight elsewhere, the activities of a pair of eccentric 'crab crawlers' on the Exmoor Coast and at Baggy Point went completely unnoticed.

The suggestion and potential difficulties of coastal traversing is also given in Arber's text providing, ' . . . studies as serious as those which were necessary when, in former days, some untrodden Alpine peak was to be attacked'. These words were of little deterrent to Archer and having enlisted the help of Cecil Agar, made plans to complete the traverse of the coast from Porlock to Saunton Sands on the north side of the Taw estuary. Over a number of years from 1954 onwards, the pair tackled their project until many sections from Porlock to Bull Point, just north of Woolacombe were completed; a horizontal distance of more than forty miles involving some climbing, lots of scrambling and many serious approaches and escapes on steep, vegetated terrain. Archer published his descriptions of his horizontal endeavours in the privately published Coastal Climbs in North Devon in 1961 to little acclaim. Probably due to the publication of the Culm article by Pyatt and Lawder, Archer contacted the Admiral and asked for help with the Baggy Point section of his project for which he did not have the necessary technical skills. A large team which included, Archer, Pyatt, Agar and Lawder descended into Scrattling Zawn and explored to the south.

Shortly after Archer published a supplement which detailed these explorations, he was badly injured, breaking his femur in a climbing accident at Lym Cove on the Exmoor Coast in 1965 from which he never recovered, and died in 1967. His dream of the complete traverse of the Exmoor Coast didn't die with him and Terry Cheek along with Kes Webb and others who had known Archer, completed the monumental section from Foreland Point to Combe Martin in a single push in just over four days in 1978; truly a serious and arduous expedition involving long sections of technical climbing that Archer had avoided through careful study of the tides.

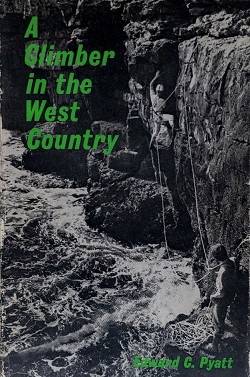

In early 1968, a book was published which was to alter the course of climbing in the South West; Pyatt's 'A Climber in the West Country' laid out in detail for the first time, the climbing potential around the peninsula. It gave detailed information about where climbing possibilities could be found, especially on the North Coast of Devon and Cornwall. Pat Littlejohn and companions didn't hesitate to make use of the information within. I'll hand over the reins to Pat for the next instalment.

For more information visit The Climbers' Club website.