Andy McVittie talks us through how to train improvements in heel hooking and reduce injury risk from them. For more information, visit Andy's website here.

This article is inspired by a noticeable increase in patients with heel hook-related tales of woe and a personal desire to improve my heel hooking skills if I'm ever going to tick that bloody project. It's a non-technical, generalised look at how to train to improve heel hooking ability and reduce injury risk from them.

Heel hooks help keep your centre of mass within your base of support. They reduce the effort needed to maintain the last vestiges of friction on the sloper you're optimistically believing will stick. They're amazingly useful but tend to put our legs in unfamiliar positions and then ask you to pull as hard as you can. Climbing does this to various parts of our body and we respond to that by training them to match the demands.

Skill practise and its benefits for becoming competent at the technique is essential and has been well-covered before:

Most of us will have played around with variations when trying problems, but does anyone physically train for heel hooks? Strengthening should both improve your heel hooking ability and reduce injury risk. So, we need to strengthen our hamstrings, don't we?

Heel hooks can see us bunched, statically, with our knee near our head, or exploding out sideways at our full reach. The forces can be applied most strongly at the knee, or the hip/groin. All muscles will always be active, but some will be stressed more than others in different positions. This is important when we consider what muscles we want to target for climbing specificity – the needs analysis.

Hamstrings refer to the muscles on the back of your thigh. They begin on your sit bones and end just past your knee. They bend the knee, help turn the thigh and help straighten the hip in certain positions. Though they get stretched when we bring our knee up, if the knee is also bent the overall stretch is relieved somewhat.

The hip adductors will now become the dominant force producer as the dangling right leg and left-hand moving have changed the centre of mass and base of support relationship. A more inward pull is now required to find stability. The right leg may press sideways/up into the roof below for compression.

Hip adductors bend, rotate and straighten our thighs. Adduction means to move a body part towards our midline. They are active all the time, stabilising and moving the hip and thigh and are what people often refer to when they talk of a groin strain. They are also the primary hip straightener from over 45°. Do we do many heel hooks with hips less than 45 degrees flexed?

An inward pull towards the wall is internal rotation and adduction of the thigh – the job fulfilled by the adductors. The pull required is increased the lower the opposite side of the pelvis is compared to the heel hooking side; think lip traversing.

As you bump along hand moves with a heel in the same place, the hamstrings and adductors will be lengthening as you go – an eccentric contraction. But our hip position when we do this means it's likely the adductors, not the hamstrings, that will take the majority of the strain at the hip. As the leg is straightened, both the adductors and hamstrings will be under long lever loads in an anatomically inefficient position. It should be obvious we need to strengthen these muscle groups through their full available ranges (with some emphasis on end ranges) and the structures (ligaments) of the inside and outside of the knees to improve heel hook performance and reduce injury risk.

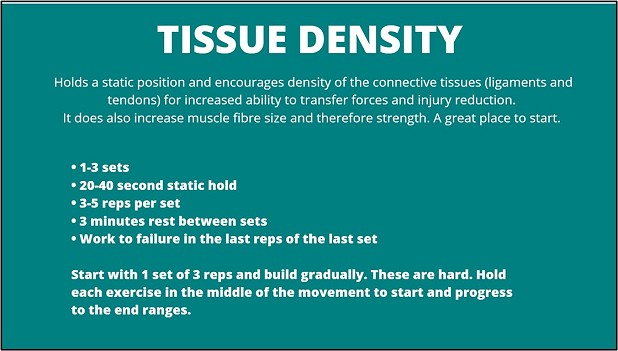

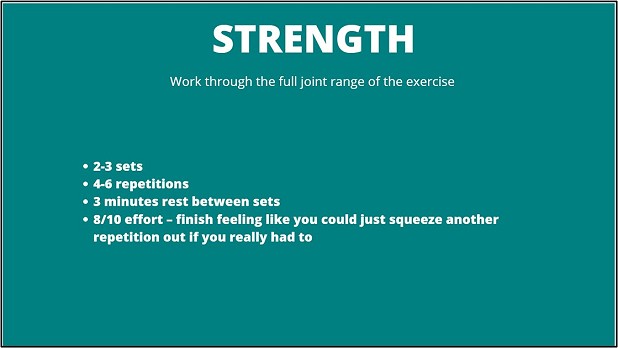

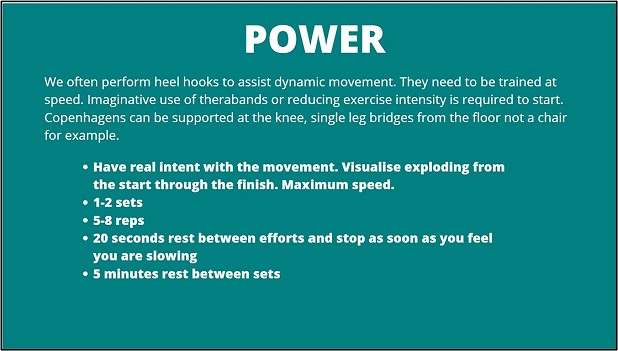

I originally wrote out a detailed programme involving gym equipment and weeks of progressions. However, this discourages self-experimentation, individualisation and puts barriers of equipment, time and space/access in the way. So here are a couple of my favourite exercises that require little or no kit and three protocols to experiment with: tissue density, strength and power. There are many variations on these exercises, so have a Google, but also think whether you are aiming for general or specific strengthening.

Hamstring dominant

- Includes a bend at the hip

- Can use outside of heel to replicate a specific move and target outer knee structures

- Can work inner or outer range of hamstrings (bent/straight hip and/or knee)

- Can be done hanging from rings or on a gym ball

- Done on your toes it can replicate the calf cramping you get from a toe down heel hook

Adductor dominant

- Different variations available to adjust the difficulty

- Targets the structures of the inner knee as well as adductors

- Engages the whole chain – rotations of the upper body in this position are a very climbing-specific exercise

Simulated hook

- Great for warming up and specifics – here I am on the toe of the standing leg with an outward turn and directly on the heel of the hooking foot with a down pointed toe to replicate the start of Pit Problem at Trowbarrow.

- Wellies are optional……

- Any sturdy object can be used. A mat behind you may be a good idea if you are extending backwards.

Feel free to adapt the exercises to suit. If you have a specific project, get specific. Inside of heel, outside of heel, knee rotated out or straight, slow and controlled or fast and explosive. All of these can be incorporated to match the specifics you require.

Don't forget to warm up at the crag if you think you may be about to do a strenuous heel hook. Static and dynamic stretching is a nice starting point. Don't worry about the reported strength loss caused by static stretching. Dynamic stretching after this negates that effect and it was a tiny effect anyway. Wrap a heel around whatever you can find, like the simulated hook above or use an easy hook to get going. Hamstring walkouts lying on your mat will do if there is nothing else. Do something rather than nothing!

As a climber, climbing coach and physiotherapist (who has also done a fair bit of running and cycling), Andy is ideally placed to provide clarity and direction to your return to climbing and outdoor sports.

A life long climber who started coaching 13 years ago, he has coached on Spanish performance improvement holidays, sport climbing, competition climbing and helped people achieve everything from ascents of El Cap to their first V11. More recently he founded a youth competition climbing squad https://processcoaching.me/ with his business partner Ellie.

Whilst his focus in coaching is technique based, his passion in physiotherapy is education, strengthening and a detailed, fully supported, return to sport. This background enables a unique, blended, treatment approach, with in-depth knowledge of all aspects of how climbing impacts the body.

2020 was going to mark his proper return to sport climbing with an aim of 7c onsight. Fingers crossed it may still happen…..

- GEAR NEWS: The Self Rehabbed Climber, by Andrew McVittie 5 Dec, 2022

- SKILLS: Core Training for Climbing 15 Feb, 2022

- SKILLS: Elbow Tendinopathy - The Boomerang Condition 2 Sep, 2020

- SKILLS: Treating Elbow Tendinopathies whilst in Lockdown 6 Apr, 2020

Comments

Only half joking but the heel hook hadn't been invented when I started. I feel weak at them and will try out some of those exercise. Pretty rubbish at those eccentric pulls and recently popped a hip pretending I was still young. Ta!