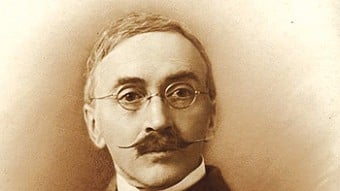

At the time of his death in 1921, en route to Everest, Scottish mountaineer Alexander Kellas was among the foremost Himalayan explorers, with a string of first ascents and an altitude record to his credit. As a scientist, his research into the physiological effects of high altitude broke new ground. So why are his achievements not better known? Sean Kelly digs through the sources to find out more.

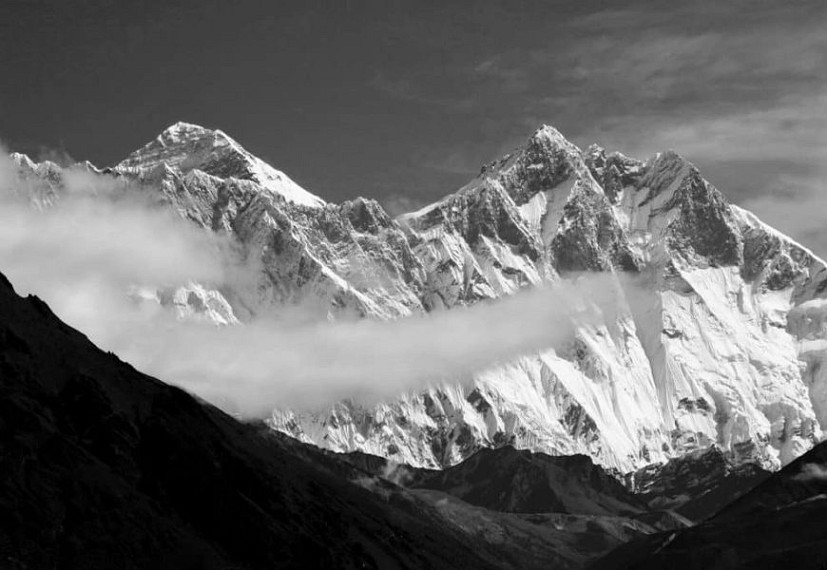

It is one hundred years since the first expeditions set out to attempt an ascent of the highest mountain in the world. Europeans had finally found their way into Africa's heart (not to the benefit of Africans); America was criss-crossed by railways (not to the good of the original Americans), and even the Arctic and Antarctic poles had been reached. But the mighty Himalayan summits were still largely unmapped, and unlike most of the Alps, unclimbed. Everest was in a sense the final frontier.

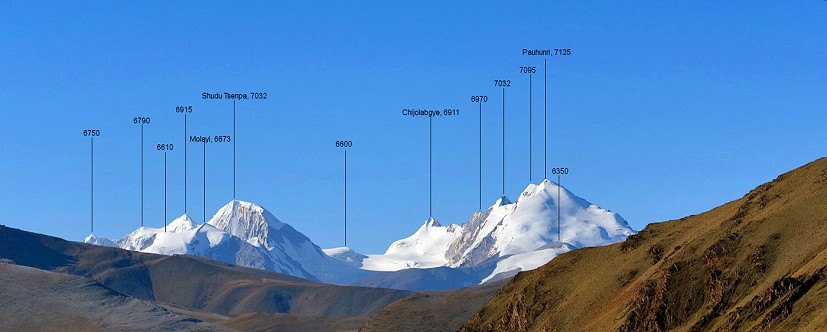

In 1911 an obscure Scottish mountaineer and scientist, with only three Sherpas for company, climbed four peaks in the Sikkim Himalayas. All were first ascents, including the highest mountain summit that had ever been attained to that date, Pauhunri 7128m (the overall altitude record had been set by the Duke of Abruzzi's expedition on Chogolisa in 1909, which reached 7,498m).

He has always been overshadowed by the likes of Mallory, Smythe and Shipton, but in terms of Himalayan experience he was the greatest of all

A few years later he climbed to 7256m on Kamet in the Garhwal Himalayas, the second-highest height attained by any expedition up to that time. Unfortunately he failed to accomplish his objective only 500m higher when, poised for a summit bid, a porters' rebellion scuppered his plans.

Though almost forgotten today, he made eight expeditions to the Himalayas before and after the Great War years. The most experienced Himalayan mountaineer of his generation, he had climbed on more 6000m+ peaks than all other climbers combined. According to Everest veteran John Noel, who was a close confident, many of his ascents involved traverses of these mountains rather than straight up and downs, then circuits around the mountain base back to his starting point.

In some respects his research into the science of human physiology and performance at altitude was even more groundbreaking than his climbing, and not followed up until Griffith Pugh's research over 30 years later, prior to the successful British ascent of Everest in 1953.

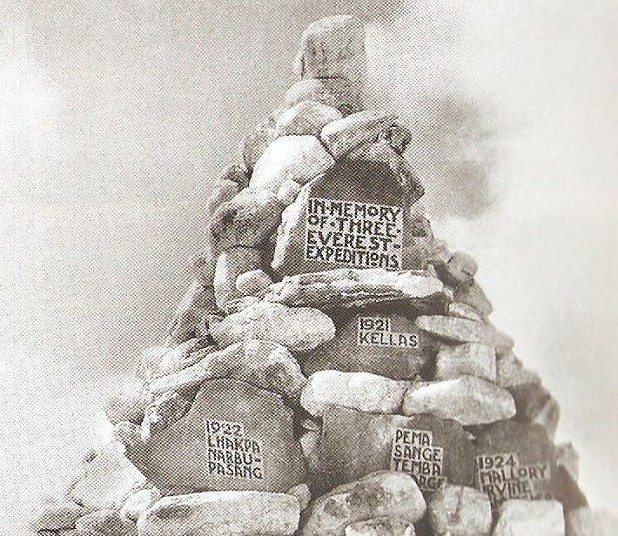

Tragically, he was to die during the approach march on the 1921 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition; in truth the first Everest death statistic.

That little-known Scottish mountaineer and scientist was Alexander Mitchell Kellas (1868-1921).

Kellas' altitude record on Pauhunri (7128m) stood for around 20 years, but was not widely recognised until nearly a hundred years later.

One of the many misfortunes of his life is that the record at the time was attributed to Tom Longstaff, who had climbed the much easier and marginally smaller peak of Trisul (7120m) in 1907. Both Trisul and Pauhunri were resurveyed in the late 1980s but still the implications were not fully realised until the publication of Kellas' long overdue biography Prelude to Everest: Alexander Kellas, Himalayan Mountaineer by Ian Mitchell and George Rodway in 2011.

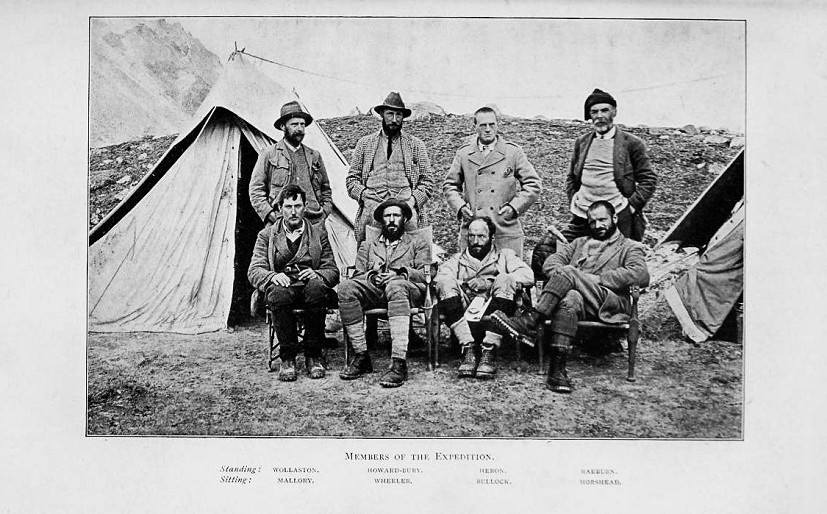

More importantly, in the course of his travels Kellas secured the closest photographs yet of the approaches to Everest, and subsequently he was invited on the 1921 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition. He died before even reaching Base Camp, from a heart attack exacerbated by dysenteric sickness brought about by unhygienic food, and so warranted only a footnote in the early history of Himalayan exploration. Up to that point it appears he was the most liked of all those on the expedition, especially by George Mallory, who wrote to his wife Ruth:

"Kellas I love already. He is beyond description Scotch and uncouth in his speech - altogether 'ncouth. He arrived at the great dinner party ten minutes after we had sat down, and very dishevelled, having walked in from Grom, a little place four miles away. His appearance would form an admirable model to the stage for a farcical representation of an alchemist. He is very slight in build, short, thin, stooping and narrow-chested; his head... made grotesque by veritable gig-lamps of spectacles and a long pointed moustache. He is an absolutely devoted and disinterested person."

Indeed, in the famous team photograph of the Expedition he is visibly absent as it was taken shortly after he died. Unaccountably, his name and achievements appear to have been air-brushed from history. Why was this? Even his commemorative inscription on the memorial at Everest Base Camp has gone missing.

There was no early indication that Kellas would go on to push the boundaries of high altitude mountaineering. As a young man he enjoyed wandering around the Cairngorms, not that far from his native hometown of Aberdeen. In his introductory seasons in the Alps he ascended the Finsteraarhorn and the Briethorn with guides, the latter widely regarded as one of the easier 4,000m peaks. He also visited Norway, but all this was very pedestrian when contrasted against the exploits of his contemporaries. Unlike others such as George Finch, Geoffrey Winthrop Young, and George Mallory, he forged no important ascents, and perhaps this makes his later achievements in the Himalayas all the more remarkable.

In 1907 he embarked on the first of his eight seasons exploring and climbing in the Himalaya, spending the months from August to October climbing first in Kashmir and later in Sikkim. There followed a remarkable series of climbs in the summers of 1909, 1911, 1912, 1913, 1914, 1920, and the early spring of 1921. He prospected the approach to some of the biggest peaks such Nanga Parbat, Kangchenjunga, Annapurna and of course Everest, getting closer than any previous western visitor.

Kellas I love already. His appearance would form an admirable model to the stage for a farcical representation of an alchemist.

In 1910 he climbed nine peaks above 6,100m during a lengthy sojourn in the Himalayas, but 1911 was his 'annus mirabilis' when he accounted for no less than four mighty summits, all but one traversed, including the highest peak then attained. Unusually for Kellas, he wrote an account of these early journeys which appeared in the Alpine Club Journal as well as presenting a talk about his explorations to its esteemed members.

This was all the more of an achievement when considering he climbed without any other European companions. After his initial foray into the Himalayas in 1907 he was very dissatisfied with his alpine guides who struggled to acclimatise to the altitude, and so dispensed with them completely, and from thenceforth climbed only with Sherpas, whom he specifically trained in basic mountaineering skills. Even this could be exciting at times as he recorded in the Alpine Journal during an ascent of Chomiomo:

"It was abundantly proved during this portion of the descent that the cloth boots worn by the coolies [sic] were not satisfactory on ice. It was misty and snowing and it was difficult to keep the ice steps clear. Twice Sona fell out of the ice steps, and on the second occasion he very nearly pulled me down, because he was so long probably at least twenty seconds before he managed to wriggle back into them."

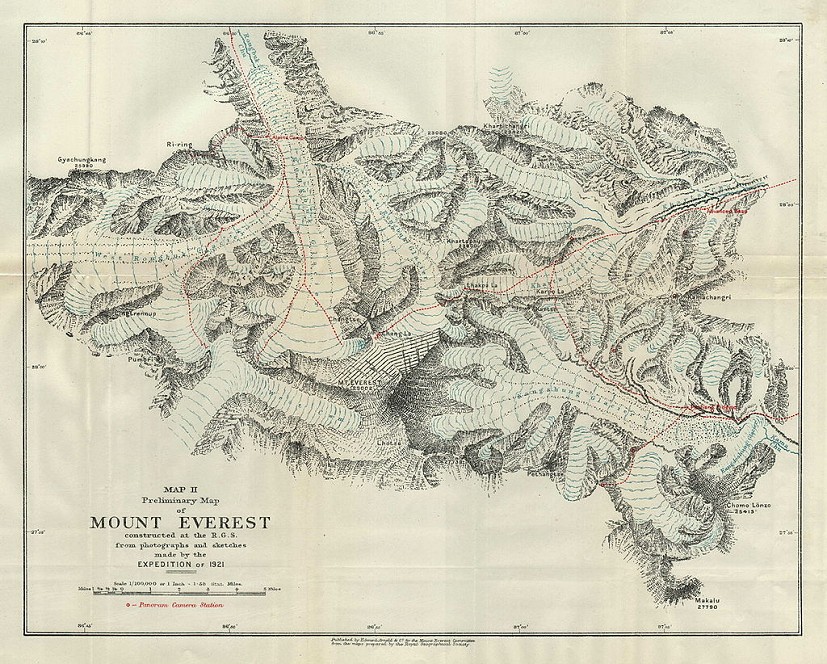

That all this was accomplished with very rudimentary equipment, minimal logistical support, and no accurate maps (the first detailed Everest maps emanated from the 1921 expedition), is all the more extraordinary. His methodology was the same as that adopted by Tom Longstaff, and later by Eric Shipton and Harold Tilman during their explorations in the 1930s, in some respects the true birth of 'Alpine Style' mountaineering in the Greater Ranges.

It is perhaps important to realise that Kellas was an extremely modest and reticent climber. Though not a recluse, neither was he a publicist in the modern sense of the word. As Craig Storti noted in his book, The Hunt for Mount Everest, he was "…of a retiring disposition". He did not seek sponsorship for his travels. He professed that he …"never rode a pony but foot-slogged every inch of the terrain, even at the lowest altitudes". Tall, thin, and slight in stature, but with extraordinary powers of endurance, he only struggled to keep pace with Sherpas at the highest elevations. Kellas seemed better able to tolerate the severe cold and thin air at these extreme altitudes.

As he climbed principally with the Sherpas, there was nobody else to write about his explorations. Indeed the only European that conversed at any length with him was John Noel. Like Kellas he too had travelled extensively in the Himalayas, but perhaps even more surreptitiously. Noel even adopted local dress so as to not arouse suspicion among the local inhabitants on his travels, foreigners not being particularly welcomed in Tibet at the turn of the century. They were both interested in prospecting the approaches to Everest, a possible line of ascent, and maybe even an attempt. As Kellas subsequently wrote to Sandy Wollaston, a later expedition colleague:

"We missed the pole after ruling the seas for more than 300 years, and we will definitely not miss the chance to explore the area around Mount Everest after having been the dominant power for more than 160 years in India […]. I would be proud to go there with two to 10 porters, even go solo, to secure that bit of exploration for the UK."

This was bold talk for 1917.

In 1913 Kellas returned from the Everest region with a stunning collection of photographs taken only ten miles from this mighty mountain. This was thirty miles closer than any previous European travellers in the region, and consequently his pictures stimulated much excitement within the Alpine Club, the Royal Geographical Society and beyond, and proved to be the catalyst for generating later British attempts to conquer the 'Third Pole'.

However, Kellas has left no written record of his journey of that year, the only record of his explorations being his conversations with Noel, and his photographs. From the Noel memoirs it appears that Kellas had been reconnoitring the eastern aspect of Everest, the Tok Tok La pass, and especially the Kharta (Karta on modern maps), and Kama valley approaches that lead to the Kangshung Face of Everest, but this proved to be something of a cul-de-sac as there was no easy access to Everest's North Ridge (that proved to be the Rongbuk Glacier approached from the north). So how had he got close enough to Everest to take his photographs?

In his book Into the Silence, the author Wade Davis suggests, from close scrutiny of Kellas's contacts with Noel, that evidence hints that because westerners were not allowed into Tibet, Kellas schooled his Sherpa companions to secure the photographs utilising a glass-plate camera. This must have included instruction on how to correctly manipulate the camera shutter and aperture to ensure the correct exposure, and to prepare chemicals and process the exposed glass plates.

They hoped for a furtive raid to Everest in 1915/16 but his ambitious plans were thwarted by the coming carnage of the Great War, and plans were not revived until the end of hostilities. The 1921 expedition, after many previous failed attempts, finally discovered a possible route to the top of Mount Everest, which was used on all subsequent summit attempts between the two World Wars. The route went from Kharta, over the Lhakpa La pass, across East Rongbuk glacier and up via the north col.

Resigning his post at the Middlesex Hospital Medical School because of ill-health, (he said on more than one occasion that he could hear voices in his head) Kellas returned to the Himalayas between August and December 1920 and teamed up with H T Morshead to partake in extensive explorations, and in the Kabru area in early 1921 to obtain better photographs of the Everest approaches, an area largely unknown and unmapped. As Shipton famously observed… "A blank on the map".

Kabru has an interesting history as it was one of the first Himalayan giants to be successfully climbed. Standing at around 7338m, the peak was ascended by W W Graham, Emil Boss, and Ulrich Kauffmann on the 8th October 1883. However, their ascent was much doubted at the time, and it is only because of recent scholarship that it is now thought that these three doughty mountaineers genuinely climbed the mountain, or rather to within ten metres of the summit. This was a remarkable achievement for the time as there was much debate whether it was possible to even climb to this great altitude, let alone attain the summit of Everest. (See The Alpine Journal 2009, p.219 Kabru 1883 ─ A Reassessment).

It was while he was resting in Darjeeling that he received his invitation to join the 1921 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition.

Aside from his considerable mountaineering achievements, Kellas, along with other eminent physiologists such as Paul Bert, Angelo Mosso (who conducted his science on Monte Rosa at the Margherita hut), Joseph Barcroft, and Nathan Zuntz, was one of the early researchers to investigate the effect of high altitudes on the human body.

When Kellas had dispensed with his Swiss guides after his first expedition, he noticed that the Sherpa appeared very well adapted for moving fast in the rarefied atmosphere encountered in the Himalayas, and so became close to several whom he could trust and respect, and who subsequently accompanied him on all of his future explorations.

He also marvelled at their sense of humour and ability to work hard while battling immense adversity, in that most trying of environments. Kellas treated his Sherpa companions not simply as porters, but as friends, and singled out two by name, Sona and Tuny. Another Sherpa with whom he formed a close bond was Anderkyow when climbing on Kangchenjhau. Indeed, he was the first to specifically train teams of Sherpas for such high altitude climbing above 7000m.

Returning to London, he conducted experiments at the Lister Institute in a hypobaric chamber, as did another Everest climber, George Finch. The results not only supported the assertion that even short periods of acclimatisation increased altitude tolerance, but also showed how important the use of low-flow supplementary oxygen could be in improving performance during exposure to extreme hypobaric hypoxia.

His studies included the physiology of acclimatisation in relationship to significant variables like altitude, barometric pressures, alveolar PO2, arterial oxygen saturation, maximum oxygen consumption, and ascent rates at different altitudes. From this research, he deduced that Mt Everest could be ascended "by a man of excellent physical and mental constitution in first-rate training, without adventitious aids if the physical difficulties of the mountain are not too great [the technical climbing of Everest's 2nd step was unknown], and with the use of oxygen even if the mountain can be classed as difficult from the climbing point of view."

His research struck a chord with Arthur Hinks, Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, who invited Kellas to speak to its members in May 1916 on the discoveries he had made and the possibility of climbing Everest with or without oxygen.

As John B West noted in his Alpine Journal article about Kellas, Hinks was remarkably perceptive and suggested: "If you could give us a paper with some general title like 'The possibilities of climbing above 25,000 feet' it would be a subject of first-rate interest ...especially since no one perhaps in the world combines your enterprise as a mountaineer and your knowledge of physiology". This was a hotly debated issue at the time. T.W. Hinchcliffe, a former august past president of the Alpine Club writing in 1876, maintained that at 21,500 feet [6,500 metres] "…is near the limit at which man ceases to be capable of the slightest further exertion."

This debate simmered for more than a century, until finally on the 8th May 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler became the first to climb Mount Everest 8848m (now rounded up to 8850m), without supplemental oxygen, so raising the bar for all future 'clean' ascents of the mountain. Kellas even predicted a climbing rate of 100 metres of ascent per hour at these extreme high altitudes — an ascent rate that very closely matched that achieved by Messner and Habeler. Perhaps it is now time to readdress the achievements of this extraordinary mountaineer and scientist.

Frank Smythe passed by his grave on the 1938 Everest Expedition and made reference to Kellas in his book "Camp Six". To reach Kampa Dzong the party had to cross a high pass of 4876m and they climbed a small nearby hill over stony rocks and scree to gain an extensive view of Everest and the surrounding peaks. They gazed in wonder at all the Himalayan giants arranged before them, before shifting their eyes to lesser peaks…

"Next came Chomiomo, Kangchenjhau and Pauhunri, three sonorous names for three noble mountains, which are linked for all time with the name of Dr. A.M. Kellas, who had died on the very pass beneath us on the 1921 Everest Expedition."

He continued:

"Before leaving Kampa [Dzong] we visited Dr Kellas's grave. The inscription put up when he died in 1921 had fallen to pieces, so we erected a slab of sandstone and Shebby carefully measured and traced out an inscription:

Kellas has always been overshadowed by the likes of Mallory, Smythe and Shipton, but historian Walt Unsworth in his epic Everest - A Mountaineering History, wrote: "In terms of Himalayan experience he [Kellas] was the greatest of all!"

At the instigation of Mallory, no less, Kellas Peak 6680m was named in his honour. It is located at the extreme northeast of the Janak Himal mountain range between Sikkim and Tibet.

List of Expeditions and peaks attempted and climbed by Kellas during his explorations in the Himalayas

It is believed that Kellas made at least ten first ascents of peaks over 6,100m in the Himalayas during a 13-year spell despite interruption from the Great War. There may be others that he did not record, as he was much more meticulous about his physiological research than his mountaineering. I have detailed below what is known.

1907 - Kashmir: Pir-Panjal range; Sikkim: Zemu glacier, Grunsee. On Simvu 6816m in September Kellas made three attempts with his Swiss guides, but failed at 6766m because of fresh snow and foul weather when aiming for the summit (Alpine Journal 34, p408).

1909 - Sikkim: Pauhunri, also known as Donghya Peak 7125m. At his first attempt in August, with only two Sherpas, he was driven back by snow and storms from 6400m.

Langpo 6950m: He ascended this from the west, on 13 and 14 September.

Jongsang La 6120m and attempt on Jongsong Peak 7462m. From the end of the Lhonak glacier, later in September a third attempt when he ascended to 6,700m on the west ridge of Jongsong, but owing to thick mist and storm, he was obliged to descend to the glacier near the Chorten Nima La.

1910 – Tent Peak (Tharpu Chuli) 5,694m in the Annapurna region. In May, Kellas ascended the ice-fall to the south and crossed the Lhonak La, 6400m which leads to Lhonak, but which he pronounced too difficult and dangerous for loaded porters.

Nepal Gap, 6400m. Later that month, he ascended it to 6858m in order to examine the summit ridge of Jonsong (Jongsang) Peak 7483m. His two attempts in 1907 had failed, the first at 5486m due to mist, the second at 5791m owing to crevasses. At his fourth and final attempt that May he reached approximately 7400m, within touching distance of his goal, but did not scale a small rock wall to the summit. Over four months he ascended nine peaks above 6,000m in altitude, and rarely descended below the 4300m contour.

1911 - Sikkim: Pauhunri 7125m climbed 13-17 June. Chomiomo 6835m ascended from the south-west in July. Dhanarau Peak 5790m.

Sentinel Peak 6490m east of the Chorten Nima La. Kellas ascended this peak later the same month, although there is some confusion here as H.W.Tobin has dated this ascent as 1910 in the H.J.

1912 - Sikkim: Kangchenjhau (Kangchima) 6920m. In August 1912, took a route from his 5,850m camp on the north side of the mountain up a steep névé and ice slope, which led to a col lying north of the Sebu La at 6400m. Reaching this col in two hours, he turned west on steep snow, at 45 to 60 degrees, climbing another thousand feet to a belt of rocks. Skirting the north side of these rocks, by which he was protected from the prevailing south wind, he attained the summit plateau some seven hours after starting to climb (Himalayan Journal 02, p125)

1913 - Kashmir: explored access to Nanga Parbat via branch of Ganalo peak (little information available)

1914 - Garhwal: approaches to Kamet (little information available)

1920 - Garhwal: Kamet 7756m. Kellas and H T Morshead attempt Meade's 1913 route from the eastern side, and reach a point slightly above Meade's Col. They failed by just 500m from the summit. The results of the field studies conducted during this expedition provided strong support for the use of supplementary oxygen at high altitude. How Primus stoves worked at high altitudes was also studied in preparation for the planned Everest expedition the following year.

Kellas returned again to Sikkim, again climbing with Morshead, and during the autumn climbed Narsingh, 5,183m. It is believed that he also reached the summit of Lama Anden (or Lamgebo), 5,867m about the same time.

1921 - Sikkim: Kabru 7338m and Mt Narsing 5800m. In the spring he worked out a new route on the ice-fall of Kabru, intending to use it later. He was also working with Sherpas training them for the trials of the forthcoming Everest Reconnaissance Expedition. Here they reached 6,400m. After only nine days resting, he joined up with the Everest Reconnaissance Expedition at Darjeeling.

Reinhold Messner & Peter Habeler after their successful ascent of Everest, ascended without recourse to supplementary oxygen thus corroborating Kellas's original findings.

Sources and research

A consideration of the possibility of ascending Mount Everest: A. Kellas. Interestingly, this manuscript, written in 1920 shortly before his death, did not appear in Kellas's lifetime but was finally published in 2001. This document contains many features that illuminate the knowledge of high-altitude physiology of the era, and the strong interest it created in the climbing community. It was preceded by A Consideration of the Possibility of Ascending the Loftier Himalaya that had been published in the Alpine Journal in 1917.

Aberdonian Alexander Kellas: The Greatest Himalayan Mountaineer of his Day. By Ian R Mitchell ─ The Press & Journal/Evening Express, June 2021

Alpine Journal: 26, 52, p113; Alpine Journal 33, p312; Alpine Journal 62, p74-75

A.M. Kellas - Pioneer Himalayan, Physiologist and Mountaineer: John B. West ─ Alpine Journal 1989, p207-213

Camp Six: Frank S Smythe. A & C Black. 1937

Exploration and Climbing in the Sikkim Himalaya. Lieut.-Col. H. W. Tobin: Himalayan Journal 02, 1930

Geographical Journal: 40, p241 ─ Geographical Journal: 57, p124, p213

Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest by Wade Davis. Bodley Head, London 2011

Kabru : Wikipedia

Kellas Peak Revisited, Northwest Sikkim: George W. Rodway & Jeremy S. Windsor. Autumn 2009

Making Everest Possible: by Buddha Basnyat MD. Nepali Times

The Himalayan Journal: 66, 2010.

The Hunt for Mount Everest: Craig Storti. John Murray Publishers 1921

The Mountains of Northern Sikkim and Garhwal: A. M. Kellas. The Geographical Journal Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1912), pp. 241-260. (A much more detailed personal account of his wanderings during a four-month exploratory journey)

Further reading

Mount Everest, the Reconnaissance 1921, Charles Howard-Bury, Mallory, and Wollaston. 1922

Alexander M. Kellas, ein Pionier des Himalaja: Paul Geissler in Deutsche Alpenzeitung Geissler, 1935

Everest: The Ultimate Book of the Ultimate Mountain. Walt Unsworth ─ Grafton Books 1991

Prelude to Everest: Alexander Kellas, Himalayan Mountaineer ─ by Ian R Mitchell, George W. Rodway Luath Press 2011

Through Tibet to Everest: John Noel ─ Edward Arnold 1927

Kellas AM. The mountains of Northern Sikkim and Garwal. Alpine J. 1912: p113–42.

The late Dr. Kellas' early expeditions to the Himalaya. Alpine J. 1922; p408–44

Kellas AM. First ascents of Chomiomo and Pauhunri. Alpine J. No. 196, p. 113

Kellas AM. A fourth visit to the Sikkim Himalaya, with ascent of the Kangchenjhau: Alpine J. 1913. 27: 125–53.

Kellas AM. A consideration of the possibility of ascending the loftier Himalaya: Geographical Journal 1917. [A summary was published in the Alpine Journal 31: 134-138, 1917.]

Kellas AM. The approaches to Mount Everest. Geographical journal 1919. 53:305–6.

Kellas AM. "Sur les possibilites de faire l'ascension du Mount Everest". Congres de I'Alpinisme, Monaco. C. R. Seances Paris. 1920. 1:451–521. 1921.

Alexander M. Kellas and the physiological challenge of Mt. Everest. John B. West,. Journal of Applied Physiology, 63 (1), 3-11. (1987).

- SKILLS: How to Navigate off Ben Nevis in Winter 20 Dec, 2021

- Better Mountain Photography Part 2 4 Nov, 2010

- Better Mountain Photography 17 Sep, 2007

Comments

Thoroughly enjoyed this, thank you!