Written in 1816, Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem is crucial not just to an understanding of English Romanticism, says Ronald Turnbull - it's also important for understanding how mountains came to matter to so many of us today. And it's not half bad either.

The E2 walking route runs from Dover across the Channel and deep into Europe – today's version ends up at Nice on the Mediterranean. Not that many choose to walk the full 4000km of the thing, maybe it's just become too commonplace? Because for two full centuries, from Wordsworth in the 1790s to Nicholas Crane in the 1990s, this project of cross-the-Channel-and-just-keep-going was pretty much compulsory. At least if you were a writer with adventure in their veins, or adventurer with a bit of a literary bent.

Fellwalking, as we do it today, was invented by the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1802 – on 2nd August, if you want to be fussy about it. Before that cloudy Monday, mountains weren't really a thing. After it, they became essential. Essential, anyway, if you wanted to call yourself a poet in the proper Romantic style.

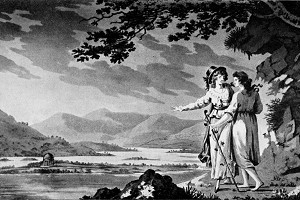

And so, in July of 1814, Mary Godwin, with her boyfriend Percy Bysshe Shelley and her stepsister Claire Claremont, fixed on a plan "eccentric enough, but which, from its romance, was very pleasing to us. In England we could not have put it into execution without sustaining continual insult and impertinence… We resolved to walk through France." Aiming in particular for "the glaciers, and the lakes, and the forests, and the fountains of the mighty Alps."

Shelley is trying to accept and experience the feelings brought on at the bottom of Mont Blanc, these strange, newly invented sensations, without any recourse to the God he didn't believe in

This was an all-new thing to do: Romantic Travel. The aim wasn't to gather souvenirs in the shape of Renaissance paintings to hang in your stately home. The aim was to experience experiences. And not necessarily pleasant ones…

The fun started straight away. To save time, they set out across the Channel in a small boat. Through the sunset and the moonlight and a gale and a thunderstorm that almost capsized the boat, arriving in France at sunrise.

Two years later Mary and Percy came again, accompanied by Lord Byron and a person called Polidori, this time making it to Geneva and down to Chamonix. The two trips combined into the 'History of a Six Weeks Tour': by the time it came out Mary and Percy were married, so she's credited as Mary Shelley. The book's put together out of journal entries with letters home by both Mary and Percy, and finishes with Percy's poem.

'Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni' is crucial to an understanding of English Romanticism in the early 19th century, and the development of Shelley's thought. Yes: but it's also important for understanding how, and why, mountains came to matter to so many of us today – in a way that they really didn't before 2nd August 1802. (What's with this 2nd August 1802? That was Coleridge's 9-day Lakeland backpack and accidental descent of Broad Stand.)

Plus, it's a pretty good poem….

Stanza II

So what do we see when we look at a mountain? And more importantly, what do we feel?

Confusion, uncertainty, even bewilderment – all of them carried by the poem's unpredictable scheme of rhymes and half-rhymes. The second stanza starts with ABBA rhymes – referring to the line-endings, here, not the Swedish popistrelles, as they perversely favour the AABB scheme. Anyway, the ABBA (again no, not the Scandi band, they have the first B the other way round, please pay attention) raises the expectation of a decorous 14-line Petrarchian sonnet. You know, the form used in the 'Mind has Mountains' sonnet of Gerard Manley Hopkins. But here it's just a trick. The nearest the next four lines come to rhyming at all is 'down… throne', while flame (line 7) turns out to rhyme with 'came' at line 11 and then with 'tame', line 20.

And turmoil also the subject matter. We're looking at the River Arve, and its 'ravine', its 'ceaseless motion', its waterfall, its cave, and yes, even that irregular rhyme scheme – it all evokes the river Alph, how could it not. Alph, the sacred river of Kubla Khan in the poem by Coleridge based on his walks along the South West Coast Path. KK, written back in the 1790s, is published (in May 1816) just as the Shelleys set out. Lord Byron has it in his pocket, and I can't believe that Percy Bysshe hasn't already read it and been blown away by it and pretty much got the thing by heart.

But where Coleridge cops out, it was all just an opium dream, Shelley is analysing, working through – indeed is actually creating before our reading eyes – the cultural, spiritual experience of standing in front of some scenery.

Stanza I

And so, before Stanza II come the brief 11 lines of Stanza I. Here PBS announces that this isn't just an evocation of raw nature. Its going to be an attempt to understand the relationship between man and mountain. His announcement takes the form of an extended metaphor:

The everlasting universe of things

Flows through the mind…

Sense perceptions trickle into the little human mind like a stream, but a particular sort of stream. A quiet, leafy stream in the woods – ah, but a stream that has its source high in the mountains,

Where waterfalls around it leap for ever,

Over its rocks ceaselessly bursts and raves…

– before going on to describe that very river in Stanza II.

And then, for the last 15 lines of Stanza II, Shelley is describing not the ravine itself but his own reaction to it, the river inhabiting not its own ravine but the 'caves of Poesy' within Shelley's own mind… And beyond even that, he starts pre-envisaging this mental ravine as a future memory…

Stanza III

So we move into Stanza III with a sense of expectation, as we approach the turn in the path where Mont Blanc, not actually mentioned so far, is finally to appear. Is Shelley going to make some sort of sense of it, as the poem has been promising? Is he going to unveil for us the Meaning of Mountain?

He's certainly going to give it his best shot.

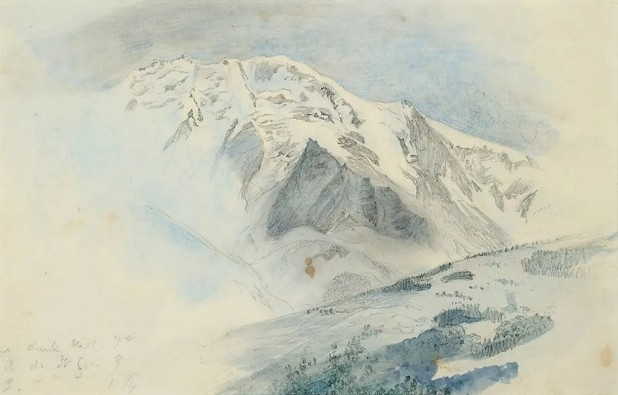

But it's not Mont Blanc in the familiar view looking up the Bossons Glacier with the crags circling in its head. This is Mont Blanc in the 'Year without a Summer' . The mountain glimpsed, just for a moment, among the snowclouds.

"Mont Blanc was before us, but it was covered with cloud; its base, furrowed with dreadful gaps, was seen above. Pinnacles of snow intolerably bright, part of the chain connected with Mont Blanc, shone through the clouds at intervals on high. I never knew—I never imagined what mountains were before. The immensity of these serial summits excited, when they suddenly burst upon the sight, a sentiment of extatic wonder, not unallied to madness."( M and P Shelley, 'Six Weeks Tour')

Is Mont Blanc, so seen, a material object at all – an image of the imagination – a dream, even a "gleam of that remoter world" seen only after death…?

The poem's so overwhelmed it can't actually describe Mont Blanc at all, but only its effect. An effect not only on the imagination but on religion or the lack of it, and even politics:

Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal

Large codes of fraud and woe

Stanza IV

So what do we see when we look at a mountain? Shelley is trying to accept and experience the feelings brought on at the bottom of Mont Blanc, these strange, newly invented sensations, without any recourse to the God he didn't believe in.

Stanza IV starts off with an 11 line listing of the natural world:

The fields, the lakes, the forests, and the streams,

through to

Earthquake, and fiery flood, and hurricane –

But not Mont Blanc. Mont Blanc isn't any of that!

Power dwells apart in its tranquillity,

Remote, serene, and inaccessible:

Serene and inaccessible: and also, in its separateness from anything we think of as life, scary.

A city of death, distinct with many a tower

And wall impregnable of beaming ice.

Yet not a city, but a flood of ruin

Is there, that from the boundaries of the sky

Rolls its perpetual stream….

The 1816 trip to Lake Geneva would also give us Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and The Vampyre by Polidori based on Byron. And yes, Mont Blanc interpreted as horror fiction.

Stanza V

And yet, high on Mont Blanc, the snowflakes fall:

… the flakes burn in the setting sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them.

And the poem ends in uncertainty, with that question posed to, and by, the mountain itself: is this really nothing much at all? Or is it

…The secret Strength of things

Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome

Of Heaven is as a law!"

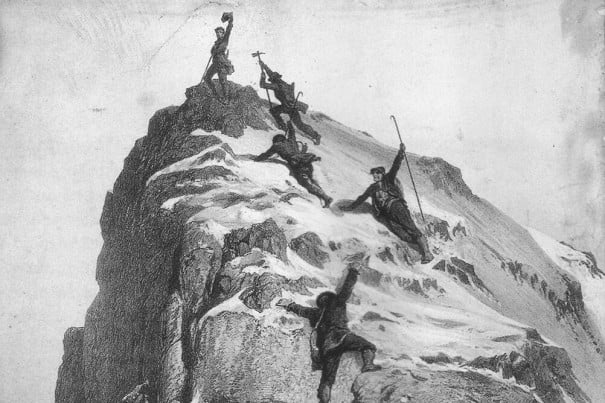

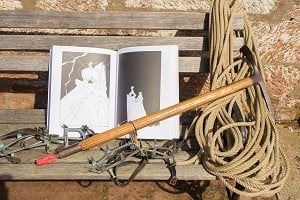

Shelley's adventure sport was small boats – he died , 200 years ago this summer, sailing one into a storm off the coast of Sardinia. Mont Blanc had its first ascent 30 years before, but it didn't occur to Mary and Percy to actually climb the mountain.

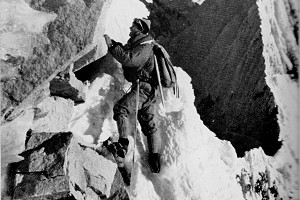

Indeed, Shelley was almost alone among Romantic poets in not climbing any mountains. Wordsworth and Coleridge rambled all over the Lake District. Byron, with his club foot, climbed Lochnagar by the grade 1 scramble called the Stuic. Even the sickly John Keats walked up the West Highland Way to the top of Ben Nevis.

But Shelley, when it came to Mont Blanc, was merely a spectator. The full account of what it is to be a person interacting with a peak: this had to wait for poets who would actually grab the thing between their fingers and poke it with their ice axes. Except – with all respect to Winthrop Young and Wilfred Noyce and even David Craig – that climber poet of Shelley-like stature hasn't actually yet come along. Meanwhile, the experience of being a bloke in front of Mont Blanc, that "sentiment of extatic wonder, not unallied to madness," is revealed by small-boat man, Percy Shelley.

- Read the poem here

- Mountain Literature Classics: Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog 15 Feb

- Mountain Literature Classics: South Col by Wilfrid Noyce 9 Jan

- Mountain Literature Classics: Free Solo with Alex Honnold 29 Nov, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: That Untravelled World by Eric Shipton 3 Aug, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight 4 May, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Menlove 9 Mar, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Basho - Narrow Road to the Deep North 12 Jan, 2023

- Mountain Literature Classics: Conquistadors of the Useless by Lionel Terray 17 Nov, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: Native Stones by David Craig 3 Nov, 2022

- Mountain Literature Classics: A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush 3 Oct, 2022

Comments

Thoroughly enjoying this series. This is not a criticism, but I can only assume the reason you didn't mention the story behind 'Frankenstein' is because you'll do another of these on 'History of a six weeks tour'.

Worth noting that MS has 'the creature' making the FA of the Eiger north face, so in a way Frankenstein qualifies as climbing literature too!

I thoroughly enjoyed this analysis. The more writing about the niche pursuit of climbing/mountain poetry the better! (I contributed a couple of articles on the subject to climber magazine a couple of years ago.) I'm interested that you place so much (tongue-in-cheek?) emphasis on Coleridge's 1802 descent of Broad Stand as marking the "invention" of fell-walking. Although Coleridge's account is a fine piece of writing, personally I don't think it's as powerful as Wordsworth's brilliant description of his earlier 1791 night-time ascent of Snowdon in Book XIII of the 1805 Prelude. And there's so much walking in the poem as a whole my feet ached at the end of it! Anyway, I very much look forward to the next article.

Thanks for the comments! Roberttaylor, the main reason I didn't go into Frankenstein etc is that these pieces are supposedly at 500 words... Yes, I do have 'Six Weeks' Tour on my list, but there's a lot of other things on there as well. The suggestion of Frankenstein as fellwalker is one to follow up on.

As for Coleridge - I did cover him a long way back, near the start of this series. [https://www.ukhillwalking.com/articles/literature/mountain_literature_classics_coleridge_among_the_lakes+mountains-12006]. My high opinion of him as fellwalker is based on his fell notebooks and letters as a whole: such as his night crossing of Helvellyn, and his verse painting of Moss Ghyll's waterfall. The series has also covered WW's Lake District guidebook, again a few years ago now. But yes, the Prelude can certainly count as a fellwalking poem, and Tintern Abbey is an account of a long-distance trail too.

I'd like to see your pieces from 'Climber' if you were able to forward them.

I'll send you photocopies of the climber articles if you pm me an address. David Simmonite (the Editor) did a very nice presentation job on them.