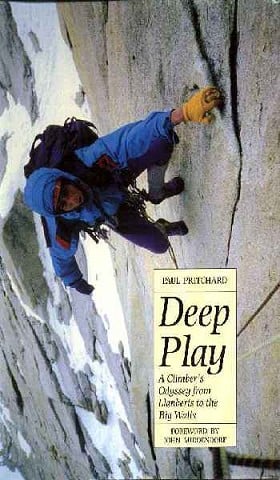

This previously unpublished article is part of a lecture Paul Pritchard gave in Slovenia, Italy and France in 2009. It has been adapted from the introduction to Paul's book Deep Play.

Playing the System - by Paul Pritchard

The Eighties was a unique era in British climbing: a time of flux. It was a time of economic depression. A generation floating between two other distinct eras. There was the climbing superstar culture of the 1970s, with its big names - Rouse, Scott, Macintyre, Boardman and Tasker - and it's major sponsored expeditions, the likes of which had not seen since the first ascent of Everest. Barclays Bank put up £100,000 for the 1975 Everest SW face Expedition. That is equivalent to millions of pounds now. This unique climbing culture was suspended between this era and the super professional rock climbers of the late 1990s to this day.

The generation of climbers who began making their impact in the 1980s, had their own peculiarities that set them apart from other generations. These differences were a result of social circumstances in the UK at the time. With millions unemployed we had time on our hands and an opportunity to forfeit the worker's life and just go climbing. It was a world which produced a crop of British climbers in the early to mid-eighties who showed the world how it was done. Climbers such as Myles, Moon and Haston were of that new 'leisure class'. They threaded lines up Gritstone edges, mountains and sea cliffs and showed others where to go. This was only imaginable after a decade of living for the rock every day, blowing off everything else. Their need to get stronger, to use all their time struggling towards their dreams, even though they had no private wealth, is what some found disagreeable.

There was a letter sent in to an American climbing magazine once deriding me for 'lacking in character' because I indulged my passion - at the expense of the British tax-payer by 'claiming the munificent British Dole'. There are many of this opinion when it comes to judging the out of work. I would like a little room to explain the system I grew up in. I would like to give those people a portrait of the Lancashire of my youth.

In 1979, after Callaghan lost, it could be said that the blanket attitude of the young began to change. By 1983 there were 4,000,000 men and women unemployed, workers' morale was sinking. Companies won contracts by paying their workers less money for longer hours. The dismantling of the heavy industries and the move toward communications and finance sucked the life out of the industrial areas. This led to a widespread loss of respect for the Conservatives in my home, a northern mill town, which still endures today. To the north of Manchester the miners' strike brought communities to tears, as the collieries of Brackley, Ashtons Field and Hulton stood silent. But, for us youngsters, this was now the land of opportunity, the government told us anything could be ours. We were free to gamble, but if we failed, we would be at the bottom of the heap.

If you were one of the lower classes that's what you did; you left school, went on the dole, and explored your creativity. Or you became a drug addict or a joy-rider. That was accepted by the majority of people; being unemployed wasn't stigmatised until a few years later. The Eighties under Margaret Thatcher was a time of mass unemployment and incredible creativity.

These unemployed had free time to develop sometimes obscure skills that seemed at first to have no use to the community. Later this would be seen not to be the case as, throughout the country, champion runners and cyclists and famous painters and writers emerged. And the young climbers of Britain soon exploited this potential. It is interesting to note that celebrated author Hanif Kureshi, who in 2008 acquired a knighthood from the Queen, actually began his artistic career on the dole in the Eighties.

At Hulton, near my home, some of our neighbours went through the picket lines to work because their families needed food. They compromised principles, though they agreed with the strikers' cause. Moral decay had been forced. Nationally this went even further as armaments became one of the biggest industries of the UK, our most marketable product, and who the buyer was didn't matter. How do climbers fit in to this you may wonder? Out of the ashes of this social, economic and moral turmoil the full time climber rose like some scruffy, bedraggled phoenix to push the boundaries of what was possible on the crags, quarries and sea cliffs.

There had already been full-timers for a while then. Bancroft, a gritstone cult hero, was probably the original dole climber back in '77, followed by such masters as Allen and Fawcett who gave so much to us younger climbers. When I stood at the bottom of Beau Geste or Master's Edge I could see them moving just as I wanted to move. I wondered if I could ever be like them. Many then could still use university as an excuse to climb. Grants were good and it gave lots of free time, and a chance for MacIntyre and Rouse to become such great mountaineers. Later, as grants decreased, students even had to work their summer holidays (as they still do) and the university life became less appealing to the dedicated climber.

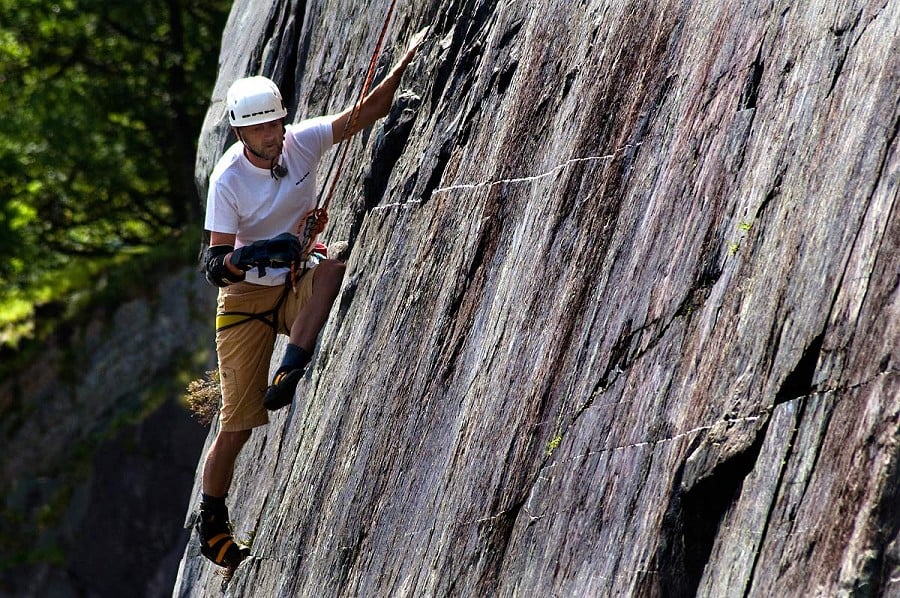

As the young athletes strove to ascend wilder and wilder rock climbs the endeavour became more time-consuming. They had to train long and hard to develop the power needed to create these masterpieces. These climbers paid little thought to the politicians in Westminster, who were inadvertently creating an environment most suitable for the serious climber. with so many unemployed it was easy to sign on. How could they prove you weren't actively seeking work if there wasn't any work to be found? And it became easy to justify too; you could go out to the sea cliffs self-righteous in the knowledge that another was working and feeding his family as a result of your sacrifice! We did look for work, me and my friends, but we were not going to go into a factory after the freedom we had tasted. That no jobs were ever offered to us by the job centre, as was the system, only reflected the economic circumstances of the country, especially in the rural areas of Wales. So why should I not use my time to go climbing? It now seems ironic that my passion contributed to the transformation of the gigantic Dinorwig slate quarries, the scar left after the community was near fatally wounded by its closure. Together we unemployed bums created, from what was once a thriving place of work, and then a vast, silent ugly space, a place of leisure for the weekend climber. And it was hard, dangerous graft, let me tell you, the clearing of loose rock and the drilling, just like the quarrymen had once done. Harder than any desk job I used to think.

But the dole handout or the government climbing grant, as we called it, paid very little. For my first two years as a full-timer, living in the Stoney Middleton wood shed or in caves around the Peak, I received eighteen pounds a week. I had to buy and sell, borrow and steal to get a rack and feed myself. We lived in the dust on a diet of cold beans and white bread. They banned us from the 'Moon' because we didn't spend enough and they thought we would give the other customers our flu.

It was a gamble climbing on the dole, to deprive yourself of all those potential luxuries for the sake of pushing up the grades. Most of my old school mates had cars and girlfriends by then. And what if you didn't make it? What would you do in ten years time if you got injured and you had no education or trade to fall back on? I still wonder. But I don't regret forfeiting the career and the consumer durables.

Some of the route names of those days celebrated the unprecedented situation in which climbing found itself, which couldn't have come about in a more healthy economic state. Doleman, Dole Technician, Dolite, Long Live Rock and Dole. One of the ardent Stoney dossers, Dirty Derek, said he'd vote Tory again to ensure he'd get another four years of Giros! But the dossers have gone now. Their generation only really lasted a decade. A climber on the dole is scum in the eyes of many now. New rules have made it tough to stay signed on for any length of time and to be a traveller, like many US climbers, is not an accepted way to live. They put barriers up in Britain and signs, no overnight parking. Now many climbers aspire to wealth and sponsorship and a sporty car as an escape from the trap of conformism. They want to attain what their heros have attained. But neither type, not the doley nor the new professional ever escapes. They both play the system.

It is acceptable to be a student, to study philosophy or art, and you can receive a meagre grant, but to filter out a little money to create great lines up cliffs is, in the eyes of some, morally wrong. It doesn't quite adhere to the system which we have manufactured. What does appear ironic now is that those unemployed - who appeared of no use to the community - having perfected their craft, were seen on the pages of magazines and in advertisements. They were transformed into heros who helped to sell the equipment the manufacturers were producing and so, inadvertently, became an indispensable part of the system they thought they had dropped out of.

To live the life we chose we rode on the wealth of others, just like the explorers of old and these, surely, must command all our respect. Shipton, Tilman, even Darwin made their journeys of discovery using the riches of the empire - from exploitation of conquered lands. They were of the original leisure class which will always be with us. They have been around for ever, almost. The working-class climbers slowly came on the scene from the thirties to the fifties. They were hard men who gained fame on the outcrops near their city homes. After the war there were enough jobs for everyone and their ascents could be made in a day or two at the weekend. As the boom babies grew up job opportunities diminished and the seventies brought the new leisure class, rebels with a rock hard cause. And now, are we heading back to the beginning? You can climb Everest if you have enough cash.

It was said in the 1980s that at either end of the economic spectrum there was a leisure class. Through unemployment the poor had the time to have their adventures, albeit on a smaller scale, on the rock outcrops close to their homes. Now this may still be true but the opportunities open to the lower leisure class would seem to be restricted somewhat when compared to how it was in the Eighties.

The first world cup finals was held in Birmingham in 1989 and won by understated Brit Simon Nadin. This and Patrick Edlingers amazing display at Snowbird in Utah was the turning point. These very public performances changed perceptions in what climbers thought the public wanted from them. Because there was zero risk involved in these gymnastic displays the public only understood rock climbing in terms of technical difficulty. Suddenly climbers could be measured against each other - winners and losers.

What followed was wholesale professionalism and the death of adventure in rock climbing. This coincided with an explosion in the numbers of climbing gyms. In the early nineties we began to see fast cut MTV style climbing on TV. Climbing was becoming more mainstream. A whole different class of people were exposed to climbing. The kind of person that craved fame instead of peer recognition.

No climber could get peer recognition with the intention of getting peer recognition. Those people are just laughed at. The only people who did it were the ones who were 100 percent bonafide bad ass. Because you couldn't fake it. You couldn't do these things with the intention of getting famous. You could only do it if there was a burning desire to push the boundary of what was thought possible and, sometimes, what was considered acceptible.

Nobody told you to your face that you were a great climber. Respect was a very subtle thing back then - it may have been just a line in Mountain magazine. There was never any mention that any route was 'The hardest in the world', that was all done retrospectively. So John Redhead's ascent of 'The Bells, The Bells' was only regarded as the first E7 in Britain as numbers began to be important.

So, we now had a situation were some climbers were not interested in peer recognition. Their sole aim was to impress the non-climber. The public understood, to a limited degree, numbers so in the 1990s climbers became more absorbed with numbers.

About that time big business also came into the climbing scene buying out small climbing gear manufacturers and pretty soon you have huge trade shows run by business people who didn't know much about climbing. They are the ones who were more impressed by the public view and less by the climbers view.

There was a perception shift in what the pursuit of difficulty was. Numbers as opposed to the testing of oneself by doing bolder and bolder climbs to enhance the adventure. Even if there was gear you often couldn't stop and put it in. Pre-placed gear was, and still is, an uncommon practice.

Throughout the 1990s, as the economy of the United Kingdom grew again and more restrictions were put on the welfare state the unemployed climber - more interested in adventure than fame - was fast becoming a thing of the past.

In a sense climbing, at least for the adventure, lost its way in the 1990s. However, the onsight bold ascent has returned in the last few years with climbers onsighting the 'headpoints' of the 1980s and making audacious first ascents on rock and in the Mountains. Dave Macleod's Echo Wall, many of Leo Houlding's ascents on rock and in the mountains are examples of this. And Dean Potter's BASE solo of Deep Blue Sea on the North Face of the Eiger really does show the future of climbing.

I knew some real characters dossing on that Peak District garage forecourt we called The Land of the Midnight Sun. They lived for the rock and material gain never really entered their heads. I wrote in Deep Play (1997) "I think when we opened the door for the new professionals some of those characters slipped out the back." Well now, after 10 long years it seem as though they are begining to slip back in again.

Finally, going back to the Eighties; all the climbers of that glorious era - of big jumpers, spandex tights and leg warmers - should thank Margaret Thatcher for giving them a golden opportunity. Cheers Maggie!

About Paul Pritchard:

Paul Pritchard (born 1967 in Bolton, Lancashire) was one of the leading British climbers of the 1980s and 1990s. He started climbing at 16 in his native Lancashire, and within a year had started to repeat some of the hardest routes in the county, as well as beginning his own additions.

Pritchard is well known for his exploits in the Lancashire quarries, as well as a string of very bold routes in North Wales, where he based himself in the late eighties and early nineties.

On Friday 13 February 1998, Pritchard's life changed drastically when he was hit by a large boulder as he was climbing the Totem Pole, a slender sea stack off the coast of Tasmania. He was left suffering from hemiplegia, a condition that robbed him of feeling and movement in his right side and which caused his speech and memory to suffer.

Pritchard has written three books:

- Deep Play (1997) is about his early climbing experiences

- Totem Pole (1999) about his accident and his recovery from it

- The Longest Climb (2005) continues his story of recovery

He won the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature for each of the first two of these, making him the only person to have won the award twice. Totem Pole was also awarded the 1999 Banff Mountain Book Festival Grand Prize.

- You can read more about Paul on his website: www.paulpritchard.com.au

|

Comments