In October of 2012 Rob Greenwood and Jack Geldard travelled to the Hongu valley in the Nepalese Himalaya to attempt the north face of Peak 41 (6648m). The peak has officially been climbed just once before by a Slovenian expedition by the less technical west face back in 2003.

The pair did not reach the summit of the mountain, but were turned back by rotten rock and dangerous snow at around 6000m after two days of climbing. Here we have a description of their attempt on the mountain written by Jack Geldard. For a more detailed 'Expedition Report' you can read Rob Greenwood's Website.

Peak 41 North Face Attempt. Day 1. Scared.

I lay awake wrapped in two sleeping bags, waiting for my 3:45am alarm, hoping it would never come. At around 3:30 I heard movement from the other side of the base camp, and I knew Rob was up and packing his gear, well before his alarm had gone off.

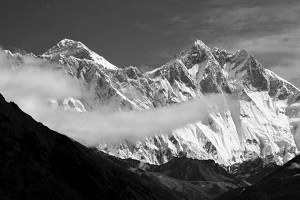

I crept my fingers out of the tent, pulling the frozen zip just enough for one eye to glance out in to the night. It was cold and still. I was hoping for a storm, a snowfall, an excuse, but there was nothing but a huge Himalayan face eerily lit by the moonlight. I ignored the face and I ignored my half-packed rucksack and I went back to being terrified. Then, like a bomb in a school, the alarm went off.

Breakfast of tea and porridge passed quickly, and I passed my porridge to Rob, a man who can eat in the face of adversity. I was in a state of near psychosis, but I hoped Rob wouldn't notice. I found out later that he had.

Back at the tent, my headtorch died, which was odd, as the batteries were brand new. Another omen. I forced on my frozen boots, at the last second opting to wear a slightly thicker pair of liner socks than normal. The boots felt too tight. Argh. Rob was waiting, hopping from one foot to another in the -10°C gloom. First the torch, now the boots. I was flustered, angry and not thinking straight. Not good. Not good.

Rob waited patiently as his ridiculous climbing partner wasted more valuable time stripping off boots and socks. And then, no more excuses, we were off.

I was behind by some margin as we hit the snow-dusted approach slopes, making tedious progress over loose rock and moraine. The distant head-light bobbed along, almost gayly (was he actually singing to himself?), the gap between us too large for conversation, not that I had any. My nose ran, my face froze and I concentrated on not turning an ankle in the collapsing boulder field.

We reached the huge snow couloir at the foot of the north face of Peak 41, took our axes and began to climb.

With each kick, with each swing of the axe, my mind became absorbed and quiet. The fear, so strong just moments before, dropped away like the ground beneath me. I was just climbing, nothing more, nothing less. We climbed on as day quietly broke around us, shadows dancing and playing on the deep walls of the gully. The hugeness of the face became apparent as features that were hidden by darkness showed their true size.

We were concentrating hard. The snow was dangerous; endless windslab over bottomless sugar-snow. Boards of slab the size of kitchen tables broke away and skidded down to oblivion. We kept to the side of the gully and pretended everything was ok. Occasional ice bulges guarded progress, not technical as such, perhaps grade 3, but enough to give stopping points, rests, a mental break from the continuous avalanche slopes.

The thin ice gully we had hoped to access was tantalisingly close, but was guarded by an 80m ice smear, just 2 inches thick. It was hard and steep, but climbable, it teased us. A fall from this ice smear would be fatal, it would take no gear for at least 50 metres. We decided that this was not the place for deadly gambles, but the mountain gave us another option, a steep ice and snow couloir that was hidden from view until the last second. The couloir skirted left-wards and joined the ridge we were aiming for. We smiled and ploughed on.

The terrain steepened and for the first time we roped up. A sheet of good ice was covered in 8 inches of rime, which made for slow but safe progress, as ice screws could be dug out whenever nerve began to waver. The top of the icesheet steepened even more, and pushed us rightwards against the rockwall. This was our first experience of the rock on Peak 41 and it wasn't good. Frost shattered shale that would take no weight, no gear, and no prisoners. Finally we popped out on to the ridge, tired, surprised at how little progress we seemed to have made, but happy with a safe bivvy spot, that would get morning sun.

"You call that flat Greenwood?" I shouted over as Rob was trying to cut a ledge.

He looked up briefly, almost bent double with exertion, breathing heavily.

"You'll never make a plasterer." I said.

He gave me the fingers, smiled, and sat down, tired.

We watched nightfall over Everest and settled in to our tiny bivvy tent, waiting for the sunrise.

Peak 41 North Face Attempt. Day 2. A sense of wonder.

Morning came and and with it my feet, numb after being pushed against the tent wall, came back to life. The morning was stunning. Spirits were high, bodies were tired, but the elation of being in such a wondrous place, with such a good friend, energised my legs and made me eager to tackle what lay ahead.

With a smile on my face I set off from the bivvy, well more accurately, I let Rob set off from the bivvy and do what Rob does best – go first.

We moved together, crossing a snow bowl and reaching a further gully leading to a ridge that would hopefully take us to the summit. The snow was poor and Rob wallowed in deep powder, occasionally hammering joke pegs in to the rotten gully walls. We ploughed on.

The steepness of the gully increased just before the crest of the ridge, and this section took trail-breaker Greenwood some time to swim up. I followed, thankful for the track he had made, although as the snow collapsed so much, it wasn't of much use. We'd left the sun of the bivvy and once again entered the world of Himalayan north face climbing. It was of course cold, and the stress of keeping fingers and toes warm was a constant companion.

After a sustained lung-bursting effort, Rob flopped on to the ridge. It looked bad; he was kicking with his legs, squirming with his body, a technique I can only assume he uses more regularly on gritstone top-outs than Himalayan faces. He thrashed around like a fish on a hook, and eventually, when he had balanced himself seesaw-like atop the crest, head in the sun, feet in the shade, he caught his breath and shouted down to me; "the ridge is a no go".

The ridge was unclimbable it seemed. We'd climbed ourselves in to a cul de sac.

Whilst Rob's world was literally collapsing around him, I was losing feeling in my feet, having been stood in deep snow in the shade without moving for around an hour.

"I'll try and rig something to abseil from" he shouted.

"I'm going to untie from the rope and solo back down" I replied. The 60m of rope between us was clipped at mid-height to a peg pushed in to some terrible shale. I figured that having no one on the end of the rope was less dangerous for Rob than having a partner with frozen feet.

Rob didn't really answer coherently, although he did acknowledge the plan, but he was busy wrestling with snow and shale, and I quietly untied myself and started to down-climb to the ledge we had cut. I couldn't help Rob, so I concentrated on my climbing, passing a steep rocky section that was dusted in useless snow, axes scraping blindly, crampons catching, and heart leaping.

Back on the ledge, I sat on my pack, wrapped myself in everything thing I had, and hoped Rob was going to be okay. Time passed and what looked like an abseil anchor seemed to have been built. I was later to find out that the only belay Rob could build was by using a Bulldog as a sort of James Bond style grappling hook over the ridge, which explained his tentative approach to abseiling.

Back at the ledge, we briefly discussed options, but really both of us knew we had been defeated by the mountain and were ready to turn around. Rob, keen as ever, was itching to start the long abolokov journey ahead, and was sorting his gear. I looked around me at the vista; Everest in the distance, with its continuous wind-plume drifting like smoke from a factory chimney. The long, empty valley beneath me. Peaks all around, not a breath of wind on our mountain, and blue sky above. The hugeness of the place engulfed me, and I felt my insignificance.

I pulled out a bag of jelly babies and asked Rob if he would mind if I just sat for half an hour. I told him that this might be the only time I am halfway up an unclimbed Himalayan face with a view of Everest. He looked around, smiled and agreed. I gave him a jelly baby.

A mixture of emotions welled up. All that time, energy and focus and we had 'failed'. And yet here we were, in this place, two friends, a view that really my words can not do justice to, an experience that I will never forget; a moment in time, that without this 'failure', I would never have experienced. Suddenly we weren't in a rush, and the stress of the summit had been taken away.

I slowly pulled the head off another jelly baby, and gazed out across the valley. I sat quietly, knowing that this moment, right now, this was it. This was my life. Never before had I experienced such a sense of being in the moment. When technical climbing, when you are in the zone, concentrating without thinking, arms and legs moving fluidly and the mind focused but quiet, it's a special feeling and one that comes all too rarely.

But this was something completely different. A slower sensation, a more contemplative experience. A sense of wonder.

Sir Ernest Barker (Introduction to the book 'The Spirit of Wonder')

>>> I wonder if I was hypothermic. Or perhaps it was the lack of oxygen.

Peak 41 North Face Attempt. Day 2 Part 2. Retreat.

Eventually the time came for us to move. Although sitting drinking in the view was sublime, we needed to start the descent to avoid another night on the face. After anchoring the ropes to a rock buried in the snow, we hopped over the ridge in to the couloir, from the sun to the shade, like two men vaulting over the handrail of a ship. My mind now focused on descent, I was once again back in the physical world of snow and ice. The ropes hung 60m straight down the couloir, yet they hardly entered this huge icy snake. This retreat was going to take some time.

We made steady progress down the ice, a system developed naturally; the ice anchors were built, backed-up and stripped out in a factory like process. Little was said between Rob and I, just occasional phrases, the familiar shouts of 'Rope free' and other climbing calls were all that punctured the soft silence of the gully, and we inched our way down the face, like ants on a house wall.

When the angle lessened we decided to pack away the ropes and down-solo to increase speed. One of the things that I enjoy about climbing with Rob is the ease of decision making. We seem to make the same decisions at the same time, meaning conflict is kept to a minimum and much of this decision making goes unspoken. This I think is the sign of a good climbing partnership.

A ledge was stomped, we traded a few words, coiled ropes and then once again started our silent descent. After a few hundred metres, I stopped to take some photographs, and Rob continued down the couloir, reaching a steep ice-bulge. Not wanting to down-solo this steeper section, he reached for his rope and cut a snow bollard anchor. The snow was in general quite poor, and we had been taking care throughout the day.

I reached the bollard just as Rob was weighting the ropes for his 30m abseil. We knew the anchor was mediocre, and Rob eased his weight on to the rope. It held.

Part way down the bulge Rob must have jiggled slightly on the rope and, like a wire through soft cheese, it cut halfway through the bollard in a second. SHIT. I shouted at Rob to get his weight off the rope, and he teetered forward on to the front points of his crampons. He down-climbed the rest of the section.

If the rope had cut through the whole way, the most likely outcome would have been that Rob would have fallen around 700m down the face, although perhaps he would have come to a stop in the snow gully. Either way, I was glad we didn't have to find out. The strength of a few snow crystals, the weight of Rob's pack, the friction on the rope, just these little things had, in that split second, added up and altered the course of both Rob and I's lives forever. Rob smiled and suggested I climb down the ice instead of abseiling. I did.

Had we become complacent? We were around halfway down the face, with only easy ground below us, and yet this slight mishap could have been terminal. I shook my head and reminded myself just how dangerous a game it is that I play.

Endless but uneventful down-climbing brought us to the base of the mountain, and the weather had taken a turn for the worse. Peak 41 reared up above us, shrouded in mist and snow, and the wind picked up. We could no longer see the huge couloir that we had just descended. I pulled the zip of my jacket up tight against my face and turned, pressing on toward base-camp, feeling lucky that we weren't stuck on that upper ridge.

The slog across the moraine to reach the comfort of our tents was long and painfully slow, yet I was glad to be stumbling over the rocks, and panting my way up the hillside. The short but unforgettable journey on this Himalayan face had taught me a lot. It had taught me about the levels of fitness required for this kind of endeavour, the strength of mind needed for multiple days out on a mountain like this, and of course I had experienced a range of emotions; dread, elation, terror, relief, wonder, connectedness, disappointment, joy, and more, all distilled to within a period of 48 hours. But more than anything else, I think this trip taught me the meaning of being in the moment and it opened my eyes even further to what a wondrous world we live in.

I was exhausted, hungry and cold, but despite these hardships, by the time I reached base-camp I had pieced together a plan. Though this adventure was not yet finished, the next one was already in the offing.

"Rob..." I said. He looked up, and I continued; "I have seen a picture of a cliff on the internet..."

About Jack and Rob:

Jack is sponsored by Marmot , DMM and Evolv

Rob Greenwood is the Regional Development Officer for East England for the BMC. He is an overly active climber, runner, and mountaineer and is currently based in Sheffield. He has climbed in a wide variety of styles in many different places across the world, but strangely hung up his ice axes after this trip last October. He is thinking of dusting them off once again for the coming winter...

Rob would like to thank Mountain Equipment, Marmot and Goal Zero for their support on this expedition.

Both Jack and Rob would like to thank:

Mark Clifford Memorial Trust, Chris Walker Memorial Trust, Jeremy Willson Charitable Trust, BMC, Sport Wales, the Alpine Club, and The Mount Everest Foundation for their invaluable support / funding / advice.

Comments