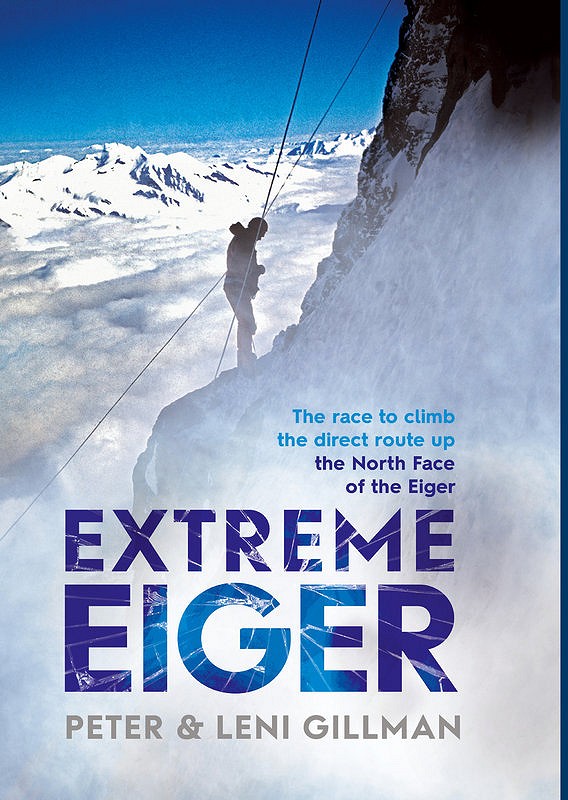

Peter and Leni Gillman, authors of Extreme Eiger, tell the updated story of the 1966 Eiger Direct.

Should they give up? Or go on? That was the question confronting the two teams attempting the Eiger North Face Direct in March 1966 after the leader of the American/British team, John Harlin, died in a fall. The teams had spent four weeks on the attempt, climbing between storms at some of the highest technical levels achieved in the Alps. For Harlin’s team the American Layton Kor, schooled in Colorado and California, had made crucial leads on rock and Chris Bonington, alternating between climber and photographer, had led an 80ft ice-pitch which he still considers the most desperate of his career. The rival eight-man German team, sometimes following parallel lines, sometimes sharing the same route as the Harlin team, had been equally stretched.

Harlin died on March 22, when a fixed rope below the Spider snapped where it ran over an edge of rock. The climbers’ initial stunned response was that they should give up the attempt. But then other views emerged. Some, like the German co-leader, Peter Haag, who knew and liked Harlin, still insisted they should turn back. His fellow leader, Jörg Lehne, disagreed, arguing that to do so would be to nullify all the efforts of the previous month. In Harlin’s team, Kor was ambivalent, saying later that no climb was worth a life. The strongest voice for continuing was that of Dougal Haston, who echoed the Germans in asserting that the best way to give Harlin’s death meaning was to continue to the summit and name the route the John Harlin Climb.

The decision was made: Haston and four Germans, all of whom had been above the point where the rope broke, would go for the summit. The others would return to Kleine Scheidegg, while Bonington would climb the West Flank, partnered by Mick Burke, in the hope of greeting and photographing the climbers at the summit.

It was the prelude to three dramatic days on the face which before now, even almost fifty years on, has not been fully told. That evening the five climbers consolidated their positions in the Spider and the Fly. They were 400 metres from the top but the summit headwall was unknown ground and a major storm was forecast. On March 23, climbing was delayed while equipment and supplies were hauled to the Spider. Among the four Germans, Günter Strobel – the most ambitious and accomplished of the team – wanted to cut loose from the others and go for the top in two ropes. He was strenuously opposed by Sigi Hupfauer, who would have been in the B team, and Lehne ruled against Strobel, insisting that they stay together and that the lead pair continue to fix ropes for the others.

It was not until the afternoon that Lehne and Strobel got beyond the previous high-point. Strobel took two hours to climb a pitch of loose, slanting rock and then took a five-metre fall when a fifi hook broke. He and Lehne retreated to the Fly where they told Haston – with misplaced optimism – that they were close to the start of the Summit Icefield. That night Haston radioed in turn that the summit group was “at the end of obvious difficulties”. If only.

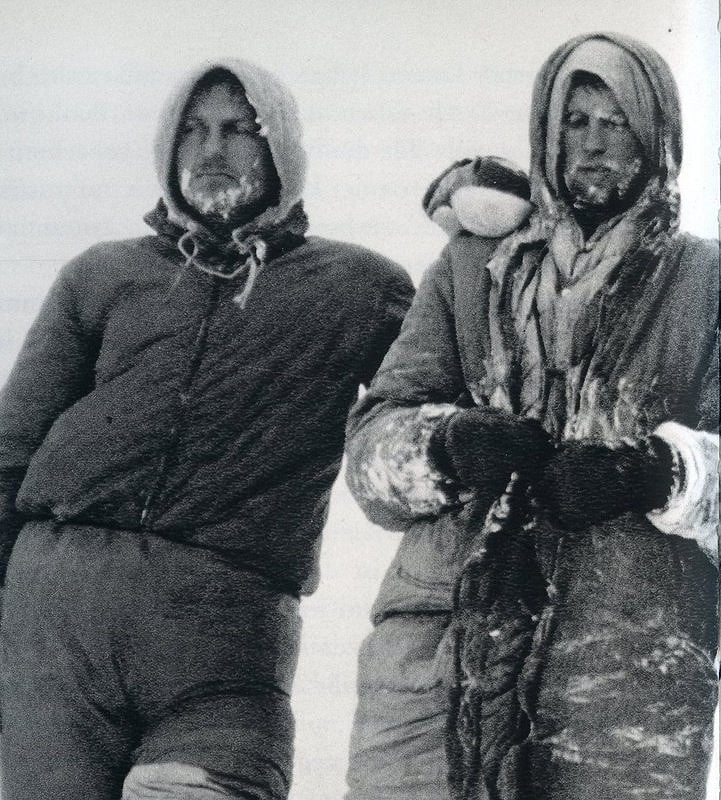

The storm broke that night, lashing the face with heavy snow and winds of 100kph. The summit group learned that the descending climbers were stripping the route of ropes, leading Haston to frame his memorable phrase: “There was no thought of retreat – the way out was up.” Almost fifty years later Strobel echoed his words: “The retreat was cut off – we had to get out.” Out on the West Flank, Bonington considered conditions worse than anything he had known in the Himalayas or Patagonia.

The climbers’ predicament was worsened by their wretchedly inadequate clothing: in those pre-breathable days, Harlin’s team wore nylon and polyurethane outers, which became drenched with condensation; the Germans wore cotton outers, which froze as soon as they became wet. Their boots were cumbersome and inadequate against frostbite; their crampons were fallible and they were still step-cutting with long-handled ice-axes. The equipment historian Mike Parsons has likened them to “bare-knuckle fighters” as they prepared to do battle.

Setting off up ice-crusted fixed ropes, his clamps repeatedly slipping, Lehne reached their previous high point by ten o’clock. It was not until midday that Haston joined him and took over the lead. Hammered by the wind, he found the pitch hideously difficult, a mix of rock and ice with only shallow cracks for pitons, and spent an hour on the final six metres.

Lehne took over on the third pitch, removing his gloves to climb an overhanging corner and then a twelve-metre chimney which he was unable to protect. He felt himself losing balance and was about to jump back down when a collapsing balcony of snow revealed a handhold and a shallow crack where he managed to place a piton. He continued up loose, shattered rock, still without protection and then followed a steep, leftwards-slanting ice ramp which led the top of a rock pillar. He attempted to set up a belay with a wooden chock and had a second narrow escape when it shot out, hurling him backwards, but he managed to grab the rope and haul himself back.

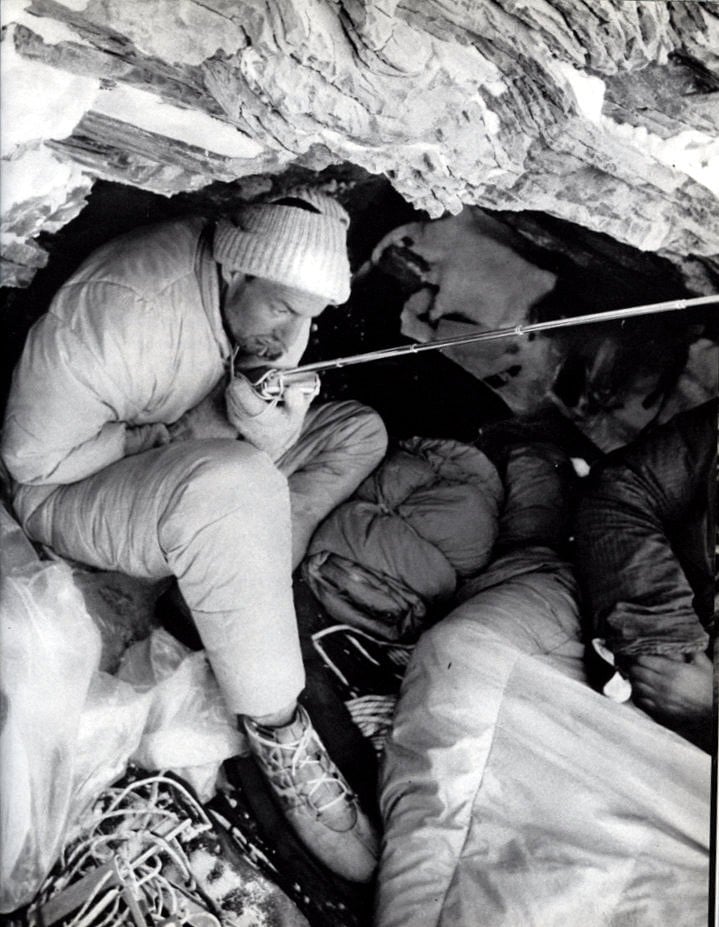

After Lehne brought up Haston and Strobel, the two Germans climbed another thirty metres in the hope of reaching the Summit Icefield. In vain. They had no bivouac equipment and were out of food and drink. They fashioned a belay stance from slings and endured a hideous night. Strobel was doubled over with stomach cramps and both men began to develop frostbite.

Haston meanwhile had descended to the Fly to bivouac with Hupfauer and the fourth German, Roland Votteler, who had been undergoing trials of their own. That morning they had lost the team’s one remaining food rucksack while attempting to haul it from the Spider. In the afternoon, Votteler was hit by a falling rock that smashed into his left shoulder, causing him to pass out. He was in intense pain and told Hupfauer to leave him behind, but Hupfauer told him to pull himself together. When Haston arrived at the bivouac site, visibly exhausted, Hupfauer gave him the ledge he had carved for himself and spent the night in a sling belay.

The next day, March 25, brought the final epic. The storm was fiercer than ever and Strobel’s hands were blistered with frostbite. Lehne pushed on up brittle layers of rock, still with minimal protection. He slipped once again and felt he was about to fall when a blast of wind drove him back against the rock. Lehne said later that the pitch – “the only possible way out” – was the boldest of his career.

The next pitch, the fifth above the Fly, brought relief at last, a sheet of ice that marked the start of the summit icefield. But although the angle was easing, the wind intensified, carrying flakes of ice past them in the updraft and threatening to hurl them from the face. At the top of the ninth pitch Lehne’s arms were cramping and he asked Strobel to take over in the lead. Strobel’s crampons were askew but, cutting steps all the way, he reached the top of pitch ten, brought Lehne up and then led on again, reaching the summit at the limit of their fifty-metre rope.

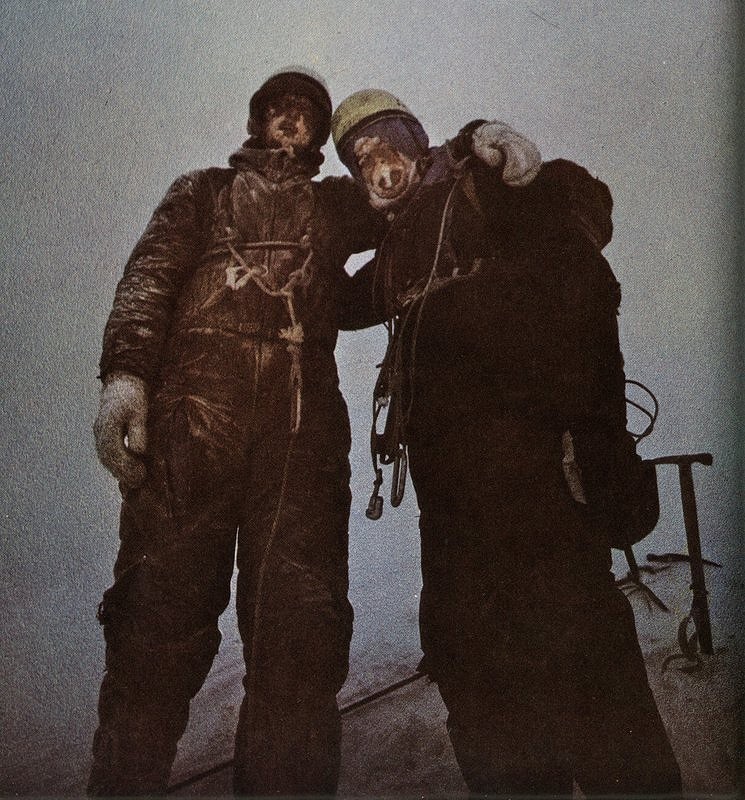

Strobel had not secured himself when Lehne mistakenly set off to follow, leaving Strobel to cling to the shaft of his ice as he battled the pull of the rope. “It was a miracle and dream,” Strobel said of the moment Lehne reached the sanctuary of the summit. Soon afterwards Bonington appeared, intent on his summit photograph. His first three cameras froze but he led them down to the snowhole below the summit and got his shot with his fourth.

Down below, Haston was leading the second group. After gulping down half a dozen Ronicol pills to stimulate the blood in his fingers and ward off frostbite, he set off to ascend the ropes that Lehne and Strobel had fixed. Behind him, Hupfauer was doing his best to assist Votteler, who had no strength in his injured left arm. They had no ice equipment with them as it had all been taken by Lehne and Strobel.

Haston’s greatest trial came at the top of the eighth pitch above the Fly, where Lehne and Strobel had run out of ropes to fix. Haston climbed the fifty-metre pitch of sixty-degree ice with loose crampons and one ice dagger to assist him, clearing the snow from the steps Lehne had cut and levering himself upwards one by one. Then came the ultimate test, when Haston made a six-metre tension traverse against his ice dagger to reach a 100-metre rope which Bonington had dropped from the summit. “Three lives on an inch of metal,” Haston wrote.

Haston continued up the rope to find Bonington waiting for him at the summit. When Hupfauer and Votteler followed, they both collapsed. There was no time for celebration, Hupfauer observed almost fifty years later. “We had to get down.” A group of eleven climbers squeezed into a snowhole high on the West Flank that night: the five summit men together with Bonington, Burke, and four Germans, talking, drinking, dozing, spluttering for breath in the confined space. They descended en masse to Kleine Scheidegg in the morning.

Four of the five summit group suffered frostbite – only Hupfauer was unscathed – as did Bonington. But while Bonington and Haston made full recoveries, Strobel and Votteler lost all their toes. After a long spell of recuperation, they were fitted with specially adapted boots and resumed climbing at a high technical level. Five of the Germans are still alive and meet from time to time, chatting, joshing, disinterring memories. Of the Harlin team, only Bonington is still alive: his view is that the climb was “incredibly challenging and probably some of the hardest climbing done in the Alps to that time. Being involved was fantastic. There’s never been anything like it for me, before or since.”

Extreme Eiger by Peter and Leni Gillman, published by Simon & Schuster, £20. Paperback to be published in February 2016, £9.99. Extreme Eiger won the Outdoor Book of the Year prize from the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild for 2015.