Acquiring an injury is a climber's worst nightmare. No matter how insignificant it may appear to non-climbers - "A finger injury?!" - not being able to do what you love can bring on intense emotions: anger, frustration, tears and in severe cases, injury can lead to depression. There is a vast array of information about dealing with the physical recovery of an injury; with books, journals, sports doctors and physiotherapists on hand to help, but how do you cope with the internalised psychological strain?

Whether it's coming to terms with climbing withdrawal symptoms, managing expectations upon returning to training or coping with post-injury fear and anxiety, there's comparatively little open, honest discussion about how it feels emotionally to be injured. Your finger might be sore, but your head could be in agony...

To gain an insight into how people manage their mental recovery, I asked a mix of five professional athletes and dedicated amateurs with varying backgrounds - and a long list of varied and challenging injuries - to share their experience of coming back stronger from injury; mentally as well as physically. To better understand the mental issues faced by injured climbers, we also contacted Chartered Clinical Psychologist and climbing instructor Rebecca Williams.

Rebecca Williams - Consultant Clinical Psychologist

How climbers cope best with injury depends a lot on their personality, typical coping styles under stress, the number of stressors in their life at the time, and the amount of support available to them. How they make meaning from the injury and resulting layoff and rehab is also important. There is no one way to best recover mentally, but we do know that people are more at risk of injury when they are already highly stressed or have difficulties with managing negative emotions. It's surprising to think that working on ongoing stress management and your ability to ride the waves of feelings can help reduce your risk for injury!

An added stressor to the injury is the fact that often once you are injured, you might find yourself spending more time with professionals in rehab than with your friends and usual social circles. The loss then is two-fold - the injury and your normal day to day routine and those people you find energising. People who can view injury as an opportunity to learn new skills and work on weaknesses can do surprisingly well, coming out mentally stronger afterwards, but that's not always easy to do when you are so close to achieving a life time goal. If your whole identity and where you get your self worth is as a climber, it can be particularly hard to swallow, and investing in other parts of your self or your life can take time. However, it's likely to pay dividends if you are successful in that balance is incredibly important for long term resilience.

Finally, if you are injured as a result of an accident and are still suffering intense imagery or flashbacks, nightmares about the incident, extreme irritability or guilt even after a month, you need to seek help. You may be suffering from a post trauma stress reaction, and it won't go away by itself. See your GP and ask to be referred for trauma based CBT or EMDR (eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing therapy, which helps to integrate and process memories so they lose some of their power).

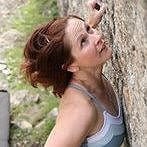

Lucy Creamer

Lucy Creamer is one of the UK's best all-round female climbers. She has suffered from a range of debilitating injuries over the past few years, but came back stronger with onsights up to 8a and a headpoint of Point Blank E8 last year.

From 2009-2012, I couldn't really climb properly, I was just coasting. So those three years were annoying and disheartening, as I felt things were taken away from me before I was ready to stop.

From 2009 to 2012 I had a shoulder injury that was tricky to diagnose, it stopped me training and pushing myself as hard as I wanted. Eventually, an MRI diagnosed a SLAP tear (in the shoulder socket, the cartilage tears away from the bone and can't reattach) and it was operated on in June 2012. Unfortunately, in January 2012 I had an accident and broke my leg which turned out to be a nasty spiral fracture of my fibula and some damage to my ankle. This needed two operations, so 2012 was a saga of general anaesthetics and rehab, resulting in me feeling very sorry for myself.

I think the shoulder (and leg) injury affected me quite badly because it felt like climbing was taken away from me before I was ready. It felt as though I may never be able to climb hard again and because this coincided with turning 40, I felt like my life was slipping away somewhat. The perceived thought seemed to be, you're in your physical prime in your 20's to 30's, so it was the timing of the injuries that I think made it harder to deal with. I felt as though I'd lost a bit of myself and struggled to know which direction to take. This was partly due to how long it took to diagnose the shoulder. If I hadn't had three years of wondering when it was going to improve, I may well have not struggled as much.

Keeping positive at times was hard due to other life factors, it was just one of those times in my life where quite a few things happened concurrently that were quite upsetting. And trying to deal with them all at once wasn't easy. But I did get involved in different things completely unrelated to climbing; I did some furniture making, featured in a 15 part BBC 2 series called 'Climbing Great Buildings', tried to learn Spanish, got to grips with a sewing machine and making things, even a bit of gardening; although it was barely more than weeding in all honesty. Photography became a keen interest too. I was also carrying on with climbing and I did have some great trips here and there but just couldn't push myself as much as I wanted due to the pain.

Although I could climb, it was frustrating because I couldn't train and push myself. But one of the good things that came out of being injured was an acceptance of not being able to climb particularly hard. So I (kind of) accepted this and used the time to get out onto classic easier routes that I had missed or ignored over the years. It was really good fun, took the pressure off but meant I got to climb some lovely routes that I otherwise may not have made the time for. And I also explored new crags that I may have overlooked because there wasn't anything I was that interested in doing there. So I had some great days out going to farther flung places and just making a day of climbing some good easier lines. It was enjoyable but after a couple of years of this I did start to wonder if there would ever be an end to it! Even though I couldn't really push hard on sport I still on sighted a few E6's when I was injured. Trad just isn't as hard on the body and I was still pretty fit, so I suppose it wasn't all bad.

I feel what I did right was really listen to the advice of the professionals. I was fastidious in doing my rehab correctly and very aware of not overdoing it. This in itself can cause more damage. You feel you are helping yourself by doing slightly more than they told you to do or using slightly heavier weights but I found with my injury, that there were strict protocols that were tried and tested and because I stuck to them and made sure I did what I was told, it got better as planned.

Having had a lot of injuries over the years, what I've generally found is that you bounce back pretty quick and a few months later you have almost forgotten there was a problem. One of the good things that happens is that if you have already put lots of hard work and effort into training, your body/muscles remember this. So although it can feel like you are starting at square one again every time you get back into it, you aren't and it is pleasantly surprising how quickly the body bounces back. Steady away though and don't go too crazy.

With my shoulder/leg injuries, what I found the most surprising thing was actually how hard climbing is. Because I'd had such a long break from it (I found it very hard to start climbing again, even when I was allowed to after the operation. In fact it took me about a year post op to get to grips mentally with climbing again), my body had changed shape and I'd lost a lot of muscle, I just realised how difficult it is as a sport on the body. It's obviously really good for flexibility and strength but starting out I was shocked at how much stress it put on my body. I just wasn't used to it, I'd always just taken it for granted, it came easily. This gave me a lot more sympathy for beginners and people whose bodies aren't so attuned to climbing and I realised just how hard it can feel sometimes.

One of the main problems I think with any injury, is the 'comeback'. As I have already mentioned, that feeling of starting at square one again, really can be a barrier to just getting back on it. But having been through that numerous times now, I now know you just have to do it. It's never easy and sometimes mentally and physically painful but it always improves and generally quicker than you think.

Because I have the luxury of time, I've found that going away to sunnier climes is a good antidote to that grim process of starting again. After my shoulder, I had two trips to Spain and it was just the perfect thing to do. I could climb lovely easier routes in the sun and just enjoy the feeling of moving on rock again. Unfortunately, when I returned it was to the depths of winter and this is why I just struggled to face getting to the wall, hence the year long gap.

But a 3 week trip to Italy with Tim and the dogs in our van was the perfect answer in the Spring of 2014 and things just zoomed on from there. This kickstarted everything and I came back with a renewed vow to get to grips with Peak limestone (it had never been my favourite) but I got really into it and had a great year redpointing routes I hadn't done before and working back up through the grades.

Another thing I found was the realisation of how attached I was to training/climbing a certain amount of times a week. This had to be cut down a lot and that was mentally hard. But once I went through the process of letting go of that attachment and realising if I only climbed once a month, the world wasn't going to end…it was quite liberating. It gave me more perspective on things.

Read a UKC Interview with Lucy - 'The Road to Recovery.'

Ben Davison

Ben Davison is a 22 year-old based in Sheffield. He redpointed 8c after having climbed for only 3 years and ticked Eye of Odin 8c+ whilst on a trip to Flatanger, Norway in 2014. Unfortunately, on the same trip Ben had an accident, in which he fell 12m and sustained a shattered ankle, wrist and pelvis and he had to undergo numerous corrective surgeries.

Take the time to think about why you enjoy climbing and you might find that you end up with a better relationship with climbing on the other side, I know I did.

Overall, it was a bit rubbish most of the time, there were plenty of ups and downs, but the downs gradually got fewer and farther between, and in the end it worked out okay. In the first 4 months, I didn't mind not being able to climb - I was more concerned with getting a properly functioning foot and wrist. In hindsight, this was the easiest bit mentally because it was simple, one-dimensional sadness. Nothing a dog or a good mate can't fix!

Once I started climbing again I think it got harder, mainly because of two things: expectations and motivation. I think I wanted to get better (at climbing) because I felt like I should get better, and I expected myself to train, diet and plan to get good at climbing. When you don't really enjoy something though, this kind of motivation doesn't seem to last. So I'd have a week or two of forcing it, give up and be disappointed and annoyed at myself for doing so for a week or so, and repeat.

This then made me question why I actually climb and whether I should climb at all if I don't enjoy it – the prospect of giving up was, I'm ashamed to say, quite attractive at times. I thought these were signs of a lack of mental fortitude, which made me even more disappointed and annoyed at myself, but, as a friend reminded me recently, if it was easy then it wouldn't have required mental fortitude to get past it!

Over time, though, as the injuries healed and as I got better at climbing, I began to enjoy climbing more, which helped my head no end. Genuine motivation came back gradually, and I went on a trip to do a bunch of onsighting which fixed my fear of falling and reminded me that rock climbing is awesome.

I have only a few bits of advice for people unfortunate enough to be going through something similar. Unless you're made of properly stern stuff then it's probably going to be hard at times, and there will probably be moments of doubt. So, first, talk to your friends about it. I can't thank some people enough for how much they helped me. Second, just try and have faith that things will get better. And finally, take the time to think about why you enjoy climbing and you might find that you end up with a better relationship with climbing on the other side, I know I did.

Read UKC interview with Ben about his accident.

Dave MacLeod

Dave will likely need little introduction, as another of the UK's top all rounders and a font of knowledge on all things training and injury-related, with a masters degree in Science & Medicine in Sport & Exercise and titles such as Make or Break to his name. Dave's list of injuries in painfully long, but ankle surgery last year has proved to be his biggest challenge so far. Here, he gives some tips on sourcing the best advice as well as dealing with the mental issues.

A 'brief' description of my injuries? Here goes:

Hands: At least 20 pulley tears, several flexor unit strains, torn lumbricals, DIP joint sprain, subluxed little finger, Dequervain's tenosynovitis, triangular fibrocartilage complex tear.

Upper limb: Chronic golfer's and tennis elbow (both arms), pronator teres tendonosis, chipped both elbow olecranons, brachioradialis tendonosis, supraspinatus tendon impingement, minor thoracic outlet syndrome symptoms.

Lower limb: Abdominal hernia, excruciating knee nerve compression, torn MCL, torn hamstrings tendon, partially torn ACL, numerous severe ankle sprains (necessitating three surgeries), severe ankle laceration, mid-foot nerve compression, dislocated and broken sesamoids, big toe tendonosis.

Despite the list, and the permanent damage to my body that I notice from the moment I wake up in the morning, I can climb harder now at 37 that I could at 17 or 27 with an un-battle scarred body.

Not that dealing with these injuries has been easy. Some of them radically changed my life, and my attitude to life. Elbow tendonosis (especially the golfer's elbow I've suffered with for 7 years) had a huge effect on me. At first I was depressed and frustrated, then a little resignation started to creep in after trying all the standard treatments over a whole year had nothing more than a trivial effect.

But then I got to a new stage of determination to find a way through the injury with healing, or at least around it with adapted climbing. I kept having the nagging feeling that it just didn't make sense that a soft tissue that turns over with new cells as part of its biological life (in health or disease) could maintain such a steady state of being injured and never heal properly. Even if I couldn't heal it, I felt like I needed to at least understand why it wouldn't heal. The lack of any signs of healing was driving me mad!

It was then I started the research that quickly became a book project to understand the wider process of how climbing injuries develop and why they heal, or do not heal, depending on what you do with them.

One of the first things I really understood from my research is the limitations of knowledge in sports medicine. I started out thinking it was quite an established and advanced science, and ended up thinking parts of it are still fumbling around in the dark in the embryonic stages of really understanding injuries. Different corners of the therapy professions seem to be operating on totally different paradigms and don't always understand each other's approach. What really stood out was the data showing how ineffective traditional methods for treating chronic tendon injuries are - lay-off, NSAIDS, stretching, manual therapies, injection therapies. People can try them all religiously and their injuries get worse in some cases! Moreover, studies kept trying to show how applying these treatments in slightly different ways might reveal a significant effect, but it there is nothing eye catching about the results. At some point, you start to think 'maybe the answer lies in doing something totally different', even though that goes against the conventional practice.

Learning to adapt to your new, slightly broken body is an essential part of a long term life of sport. That doesn't mean it's good, or okay to feel pain and limitation from injuries, but if it's happened, then it's reality.

I discovered the research and personal story of Hakan Alfredson (you can listen to him describe it on the podcast linked below) using painful, high intensity eccentrics to try and rupture his degenerating achilles tendon so that he would be a candidate for surgery. Instead of rupturing it, the tendon healed! It went against the central tenets of sports medicine - rest for injured tissue, and exercise below the level of pain. Heresy basically! Eccentrics now have a fair bit of evidence behind them but not all of it is conclusive. It works better in some tendons than others, underlining the complexity of injury development. But we can certainly take away that it pays to think openly about ways to approach an injury.

Based on 4 years of research, I applied eccentrics, and many other rehab activities and changes to my life and climbing routine and have successfully recovered from my chronic elbow tendonosis. It's probably my best achievement in climbing! Interestingly, one of the big mistakes I made along the way was backing off when I felt increasing pain during the exercises. I was still trapped in the old paradigm. It took a visit to Nicola Maffuli in London to reassure me that I needed to push through and quadruple the volume of exercises, and keep pushing into pain. He was right.

Among many lessons and practical pieces of knowledge (all of which I've put in the book for everyone to benefit from) I learned two important overarching lessons: First, for the vast majority of injuries, there probably is a way to overcome them much more quickly than the way your doctor or therapist might offer given their knowledge today. If you aren't lucky enough to find it first time, keep trying and educating yourself until you do find it. Don't trust anyone else, qualified or otherwise, to do it for you. You need to take control of your own health. It takes a huge amount of work and dedication to do this properly, but the consequences of not doing so are not worth it as far as I am concerned. Second, every injury you pick up leaves a battle scar on your body to some extent. Learning to adapt to your new, slightly broken body is an essential part of a long term life of sport. That doesn't mean it's good, or okay to feel pain and limitation from injuries, but if it's happened, then it's reality.

As always with my coaching advice, I'm trying to put my money where my mouth is. Out of the last two years I've spent half a year on crutches and had plenty of pain and frustration. Sometimes I've had to psyche myself up just to walk across a room because I know it's going to hurt. But in that time I've climbed new routes up to E8 on alpine big walls around the world, hard new mixed routes on the Ben, Font 8b boulder problems etc. It's fair to say that physically I felt like shit on some of those ascents. It would certainly been more pleasant to do them with a fresh body. But I'd rather have done them that sit in the house and complain about being both injured and climbing deprived.

Link to Alfredson's podcast.

Visit Dave's website and blog.

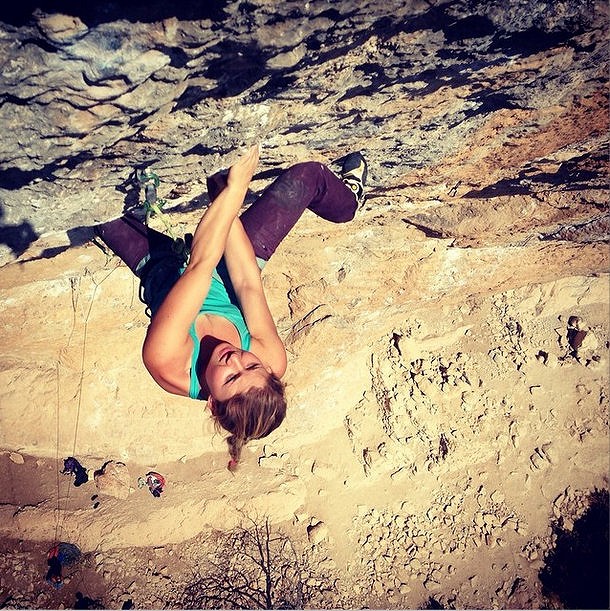

Hazel Findlay

Hazel is one of the world's best female climbers, with trad ascents up to E9 and sport redpoints up to 8c. She is currently 8 months into recovery from a shoulder operation and has just started her mental coaching business Mindful Climbing.

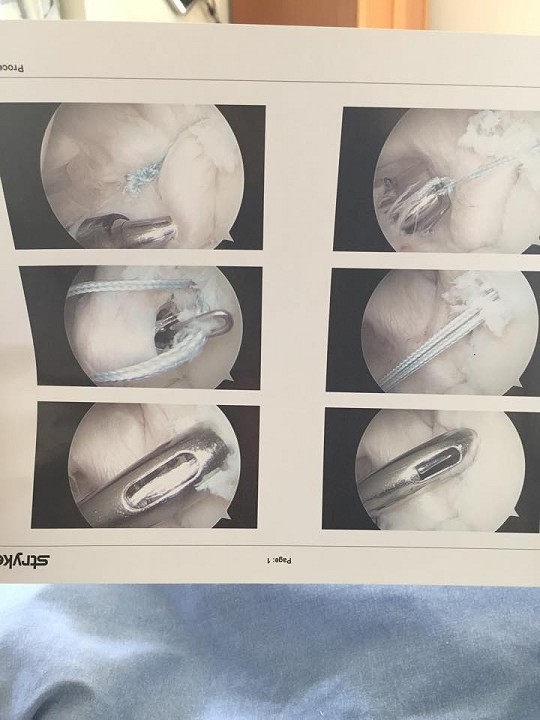

Over the 20 years I've climbed I've had a fair few injuries but none of them very major until I tore my labrum (piece of cartilage) in my right shoulder. It happened in 2010 on a route called Air Sweden. I have pretty flexible joints and this route had a few slappy/stretchy moves between a crack and an arete. Since you have no foot holds your foot usually slips and your shoulders take the strain. I loved the pitch; it's still one of the coolest single pitch trad routes I've done, but it did mess up my shoulder and my climbing for the next 5 years! So before you ask... no it wasn't worth it.

People always say - try to find the silver lining, try to take away the positives, but that kind of thinking has never worked for me.

For 4 and a bit years I strengthened the shoulder enough with physio and sort of made do: I could go for long stretches of time without any problems, but also long stretches without being able to train or try hard. In May 2014 I climbed the hardest I'd ever climbed (on paper), an 8c in Spain. After that my shoulder got really bad and I couldn't really try hard at all. I tried everything from diet to chiropractic to physio, until finally, almost a year later I got an MRI and the surgeon declared that I needed surgery. Here I am 8 months post-op and I've just about done a pull up. The day I can slap for a hold with my right arm will be a biggy!

It's been such a long road for me that's it's really hard to say how my mentality was or is or where it will go. Last summer I did learn some important lessons and for that I really thank my injury. People always say - try to find the silver lining, try to take away the positives, but that kind of thinking has never worked for me. I guess what I really learnt was how to accept the way things are and how to be patient. You can't shape the world to fit you all the time. Hoping for the best or loving climbing more than the next person won't fix a broken shoulder. But you can choose to be happy nonetheless, with whatever you have. Even though I haven't been able to climb like I've wanted to this year or really the last 5 years, I've experienced a lot of happy times, achieved a lot and that hasn't been through chance or positivity, but through a bit of effort on my part to be OK with it.

Visit her Mindful Climbing Facebook page.

Lisa Alhadeff

Lisa climbed her first 8a+, Supercool at Gordale Scar, last year. Making her achievement all the more impressive was a battle with recovering from breaking both bones in her lower leg in a bouldering fall, which occurred 4 days after starting her training plan. Refusing to let an injury get the better of her, Lisa adapted her training to her capabilities - top-roping with one leg and fingerboarding.

I think for me the recovery from a significant climbing injury could be split into three distinct stages: phase 1 - the survival phase, Phase 2 - the legwork phase and phase 3 – the developing phase.

Phase 1 was both extremely hard emotionally and yet quite simple. The biggest impact on me in the weeks after my accident was physical, and my focus was on survival rather than moving forward. The very lowest point occurred when I arrived home from hospital and my boyfriend more or less carried me to the nearest sofa. It hit me that I really was in trouble and that it was going to be a really long time before I could climb. I looked at him and pretty much started howling: and I didn't stop until a friend who'd suffered from a very similar injury phoned me about 10 minutes later. For me it was essential to be able to speak to people in similar situations and in fact I knew someone who was injured that same weekend (unfortunately) but I think it helped both of us.

"It finally felt like all the pain and effort of the last two years no longer defined my climbing, as though achieving the goal I set before I broke my leg and overcoming the fear in order to do so had freed me of some of the mental hang-ups I had." -

A large proportion of those first few weeks was based on having simple goals: I was preoccupied with my physical health and it was sufficient to have simple goals such as surviving more hours without painkillers or going downstairs. In the early days of an injury I think you get more support from friends and family and it helps that people expect you to feel miserable.

Phase 2 I think is the hardest. Often friends, family and your employer (or in my case degree) move on while you're very much in the thick of the battle. A friend remarked that people had forgotten that he'd been injured but he was still in pain every day. This is the point when you're putting in the physio, and the hours (literally) to recover. But by this point you're probably expected to be a fully functional human being: and that's hard. I struggled to balance work with recovery and to train on top of that, and there were many, many days that it felt like I was going nowhere and it would never get easier. A few weeks after my injury, I visited the wall where I was injured to see my friends. I did this several times those first couple of months and I used to go home and cry each time. It was too hard watching people climb as if nothing had happened. In retrospect, I should have met people outside the wall and when I did do that, it was a lot more enjoyable.

I realised one of the problems in phase 2 was that no-one realised how hard I was struggling: I didn't even want special dispensation, I just wanted some support. I explained to my university tutors that it took me a phenomenal amount of effort to keep up and although ultimately I never needed to take the option of extra time that they offered to complete my degree, I found it reassuring knowing they were on my side. I also found it really hard (and still do) to explain my behaviour at the climbing wall: nobody wants to make excuses for not trying, but sometimes the mental barriers take some overcoming. The most helpful thing for me in phase 2 was writing a blog – partly because it was cathartic, and partly because I'd looked to other blogs when I'd first been injured.

Phase 3 is I suppose the developing phase because it's when the psychological effects of an injury really start to become apparent. I guess I'd still say I'm in phase 3, because there are still things that I can't do because of pain but the things I can do now eclipse those that I can't. Often after traumatic injuries I think there are very noticeable effects early on, and certainly I was pretty jumpy and woke up a lot having horrible and graphic flashbacks in the first few months. However, this faded and the longer term effects didn't become apparent until later. It doesn't really matter how you were injured, I think it's impossible not to be terrified of a repeat occurrence and my climbing completely fell apart as I recovered more and more physically.

Phase three really took more emotional strength than any of the others because to all intents and purposes I was better. I was discharged and that meant there was no medical reason that I couldn't lead climb or boulder (rather than just top rope and finger board). And with that, my safety blanket was gone. As a motivated person with good friends behind me, it was not so hard to train on a fingerboard. Ok, it had its boring moments, but I was motivated by a desire to beat the challenge of injury. But I think fear really has to be fought solo: while everyone feels fear, only I could conquer my own fear. It was nearly two years since I'd last climbed normally and honestly I often couldn't remember why I was training, I just was because I did.

Still being at this point, I've not fine-tuned what helps me. However, there are two main things:

Firstly, I'm always ashamed to use it as an excuse when bouldering indoors. I don't know why, I just hate it. For example, if as a group I'm trying a problem with a very throwy move at the top people will ask why I don't try, because they didn't know me when it happened. I'll say "I just don't want to" and then I'll feel bad because that's not me. I ALWAYS try. I never give up. It's what makes me proud of myself and I'm denying that side of my personality. I wish I was more confident about saying why and didn't get hung up over it: I think it would help me.

Secondly, I had to look at fear from a training point of view. I had to admit it was a problem, and then approach it methodically and scientifically. As with most things related to emotions and feelings, there's plenty of stigma relating to fear and it's seen as desirable not to feel fear at all. Yet we do, and for (as far as I'm aware) pretty sensible reasons relating to survival. Something that's safe isn't always intuitively so. Once I'd stopped beating myself up for being scared, I started shouting it from the rooftops – and the response was overwhelming. It turned out that a huge number of people ranging from those who'd never been injured to those recovering from injury felt the same way. I suppose that this applies to everyone and not just those recovering from injury but with fear it helped me to break the problem down. I had to establish the reason for my fear, rationalise the situation to compare my fear levels with actual danger levels and then since these didn't match (fear high, danger low) practise the worst case scenario (a foot slip, falling off) over and over again until the fear matched the danger level.

Read the backstory on Lisa's blog.

Watch a video of Lisa's story and her ascent of Supercool below:

More Articles

Comments