Emily Harrington is one of the best all-round mountain athletes in the world. Her résumé includes podiums and finals in international competitions, a free ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite, sport climbs up to 8c and ascents of Everest, Ama Dablam and most recently, Cho Oyu.

Alongside her boyfriend and regular climbing partner, Adrian Ballinger - who very nearly summitted Everest without oxygen earlier this year - Emily's most recent adventure on Cho Oyu is perhaps her most unconventional achievement. An ascent and ski descent of the 8,201m mountain, taking the pair just two weeks from leaving home in the US to returning, having acclimatised and prepared at home.

I asked Emily about her aspirations for mountaineering and how she has managed to become such a versatile climber...

You are a well-rounded mountain athlete on both rock and ice and have taken part in quite a few high altitude expeditions now - Everest, Makalu and now Cho Oyu, but what inspired you initially to venture into mountaineering?

I was invited to climb Everest by Conrad Anker in 2012. Honestly I didn’t have all that much interest before that, other than teaching at the Khumbu Climbing Center in 2011, which was where I developed a fascination with the Himalaya and the mountain culture over there. I wasn’t sure about the whole high altitude thing, but I figured there are very few people in the world who are given the opportunity to climb Everest - I didn’t see any reason to not go.

How easy or difficult did you find the transition to mountaineering at first? Your background in climbing and high fitness levels must have given you an advantage, but what about the mental and emotional side - were you perhaps more able to cope through being used to the suffering through training and your multi-day climbing adventures?

At first I found it to be awful and incredibly hard. I got sick, I didn’t know how to pace myself or deal with the suffering of altitude. It’s hard physically as well as emotionally, perhaps more so if you are used to being at a high level of fitness. Altitude tends to level the playing field, and those who are used to pushing hard at normal elevations overdo it easily and end up totally crushed. It’s a weird mind game, and one where you must have patience and learn your body but as well understand that it will hurt no matter what. That was the biggest lesson I learned - altitude just hurts, and finding ways to push through that pain is the hardest part.

What did you learn from summiting Everest and having to turn back on Makalu? How did these experiences prepare you for Cho Oyu?

I didn’t know much when I was on Everest. I was just wide-eyed and experiencing it all. Looking back I realise how lucky I was. Nothing too bad happened that year, no drama, no massive accident, and yet now I realise that climbing Everest from the South side was perhaps the most dangerous thing I’ve ever done. I summitted and returned home. After more experiences on other mountains I’ve come to realise that success is actually super rare, and that accepting failure is one of the most important parts of climbing in the big mountains. Makalu was a super valuable lesson in that way. It was a huge endeavour for us, being the only team on the mountain in a hard season. Turning back taught me a lot about myself, mostly that I’m fairly accepting of failure when there are limiting factors outside of my control. On Makalu we couldn’t predict or control the snow conditions, and once it became apparent that it was too dangerous to continue I was able to turn around without a second thought. Going into Cho I was totally ready for things to not work out. We were going to do our best and be as well-prepared as possible, but there was a good chance it would all fall apart, and I wasn’t afraid of that.

How did the idea to do a rapid ascent and descent within two weeks come about - something which normally takes up to two months of acclimatisation and preparation before the climb?

I spent 2.5 months on Everest - it felt like forever. Adrian has spent probably 7 months a year for the last 18 years living in a yellow tent in the Himalaya (guiding in the spring and fall). We both love rock climbing, skiing, and being home. Going on long expeditions sounds pretty awesome at first, until you’ve done it so much you begin to dread all the downtime and wish you could still go climbing but minus all the extra time. When I go climbing, I like to do just that – climb. I love having big days, moving well, and trying hard. Most of the time I’d rather go climb something in a day than break it up into several, because it’s just more fun that way. This was our Himalayan version of that concept.

Also, usually when you return home from having spent weeks at altitude you’re weak and exhausted for a long time. Altitude crushes you and over time you deteriorate. It’s the worst for rock climbing. I was hoping that with only two weeks away I wouldn’t lose all my strength and I’d still be able to climb well.

Can you explain the training and preparation that you carried out at home? How long in advance were you starting to train? How did you manage to get fit enough and have all the logistics in place?

Our strategy involved training at home for about 3 months, pre-acclimatising in these altitude-simulator tents called hypoxic tents for six weeks leading up to the trip, having all of our logistics and organisation in place on the mountain before we arrived, our camps set, permits in place and waiting for a good weather forecast before we left home. That way we stayed healthier by staying home, eating and resting well, and blasting when the time was right.

Tell us a bit about the ascent and your timings from camp to camp - did everything go to plan?

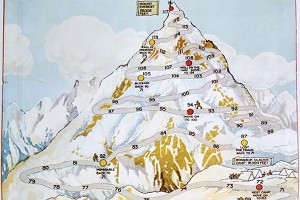

Yeah, pretty much. We had 3 possible summit days in mind - September 29th, 30th and October 1st. We ended up summitting on October 1. We spent three days in Advanced Basecamp, two at Camp 1, one at Camp 2, and then summitted and skied all the way back to ABC. The weather and logistics just worked out perfectly.

You chose to descend on skis - what was your set-up, and how did it feel after and exhausting ascent to glide down the mountain - or maybe it wasn't quite so easy…?!

We carried our skis and climbed in ski boots with neoprene overboots for warmth. We each had a fairly light set-up (carbon) but we had real skis and four buckle boots (not teeny rando racing skis or anything like that) and skiing down is way harder and more dangerous than walking down. Most of the time at those altitudes the snow conditions are difficult and variable, and making jump turns is the most physical thing you can do, I breathed so hard I damaged my trachea and developed a pretty bad cough from it. At the same time we were able to venture away from the climbing route and ski this big face, just the two of us - it’s a really beautiful and amazing way to explore the mountain and was totally worth the effort.

You chose to use supplementary oxygen - would it have been possible without?

We didn't feel it was realistic to try for no O's with no acclimatisation rotations and really not being fully acclimatised to 21,000 feet and above. Also, we were very excited about the idea of finding a cool line to ski away from the fixed lines on the descent. Not only is skiing far more physically demanding than simply walking down - some may find that surprising, but honestly, the hardest I've ever breathed was while we were skiing down and not climbing up - but it requires decision-making skills and risk management that we didn't think were appropriate under the exhaustion and fatigue of a no-O's ascent.

Both Adrian and I have tried to climb 8,000-metre peaks with no O's (Adrian this past spring on Everest and I last fall on Makalu) and it's incredible how impaired your motor skills and reasoning becomes.

How have previous expeditions affected your body, and how did Cho Oyu compare both physically and mentally by doing it in such a short period of time?

It was a super hard summit day, and I think harder than if we had had some more acclimatisation, but that’s what we signed up for. At the same time though it was so short that I think I feel almost recovered already. We didn’t have to spend so much time up high so the deterioration was minimised.

Is this style of ascent in which you prepare at home something you will use for your future expeditions?

Yeah, for me I think it’s great. I have so many other passions in life, and I prefer to keep moving and dislike downtime. I also love being home and am constantly trying to maximise my time here.

Adrian, do you see this type of rapid ascent being possible for commercial/group expeditions? How risky is it to undertake an expedition is this manner?

I think these "lightning ascents" are exciting, and lots of people are interested in the possibility. It's for a very specific type of climber who's willing to put in the work at home and gain experience on other mountains first before signing up for such a fast-paced climb. I think there are many different experiences for people to have in the mountains, and this rapid style definitely caters to a certain demographic.

Our rapid ascent programs that Alpenglow offers already cut traditional expedition times by 30 to 50 percent, while increasing health and success. Lightning ascents take it to a whole new level and require athletes with the proper experience and the willingness to suffer.

The key in making these climbs faster while still maintaining a high level of safety is all in the logistics, the guiding and the experience of the climbers on the team. Cutting corners in any of those areas will lead to accidents. That's where the risk lies. You need the preparation and to be willing to stop and turn around if everything isn't coming together just right like it did for Emily and me this time around.

You documented the ascent heavily on social media, in a similar way to Adrian on Everest earlier this year - Snapchat, Instagram etc. Why do you enjoy sharing the experiences on expeditions? Does it perhaps help to lessen the seriousness of such an undertaking, to keep it lighthearted? Some would argue it removes the sense of adventure and isolation…?

Climbing feels selfish at times. It's just us out there pushing ourselves and having a good time. But the fact is that sharing our stories seems to have value to others. We receive hundreds of comments a day telling us how impactful and inspiring our shared experiences are to people. Realising that what you are passionate about might influence some stranger to create something positive in their lives is a pretty powerful thing and something we've decided is worth the time and effort to pursue.

As a partnership, you both seem to bring different skill sets to the table and complement each other well in that respect. Do things ever get competitive or difficult to manage as a couple?

We specialise in different disciplines, so we can both learn from and support one another in a really unique and non-competitive way. Of course all relationships have their challenges, but I think that’s just normal.

In 2015 you set yourself four goals - to make finals of US lead nationals, redpoint 5.14, free climb Golden Gate and ascend Makalu without oxygen. What did you achieve in the end, and what did you learn?

I only managed to free El Cap last year, but I learned so much about training and my own personal motivations. I think it has helped me this year. I’ve already managed to achieve some really cool things I’m proud of (El Cap in a day, Peace 8b, and Cho Oyu!), and hopefully I can climb some hard projects in the Red River Gorge in November.

How do you manage to train and excel in so many areas of mountain sport and not burn out? Does your training generally correspond to seasons, where you take one discipline at a time?

I try to just mix it up. I could never just do one style year-round. I know that maybe I don’t perform at as high a level anymore because I don’t specialise, but I am a far better all around athlete now, and that’s what’s most important to me. I am still trying to work out how to train properly, it feels like a constant experiment.

What advice would you give to someone who struggles with both setting and achieving their goals?

I would tell them to try and be true to themself, to really ask themself what they want and how to get it.

What's next for you both? Will Adrian be returning to Everest to summit without oxygen, and will you have another shot at Makalu?

I think Adrian will go back to Everest. I would maybe go to Makalu, but I have a lot of other objectives as well so I will need to prioritise.

Emily is sponsored by: Smith optics, La Sportiva, Jaybird, The North Face and Petzl.

- INTERVIEW: Albert Ok - The Speed Climbing Coach with a Global Athlete Team 17 Apr

- SKILLS: Top 10 Tips for Making the Move from Indoor to Outdoor Bouldering 24 Jan

- ARTICLE: International Mountain Day 2023 - Mountains & Climate Science at COP28 11 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Did Downclimbing Apes help Evolve our Ultra-Mobile Human Arms? 5 Dec, 2023

- ARTICLE: Dàna - Scotland's Wild Places: Scottish Climbing on the BBC 10 Nov, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Loki's Mischief: Leo Houlding on his Return to Mount Asgard 23 Oct, 2023

- INTERVIEW: BMC CEO Paul Davies on GB Climbing 24 Aug, 2023

- ARTICLE: Paris 2024 Olympic Games: Sport Climbing Qualification and Scoring Explainer 26 Jul, 2023

- INTERVIEW: Malcolm Bass on Life after Stroke 8 Jun, 2023

- ARTICLE: Alexandr Zakolodniy - A Climbing Hero of Ukraine 26 Apr, 2023

Comments